Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water Leaders

Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak: An Inspiring Water Leader

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

18 June, 2021

Water is considered as inseparably linked to sanitation, and within the sanitation sector, the single name widely reckoned in India and the world alike is Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak, the founder of Sulabh International Social Service Organisation (also referred to simply as 'Sulabh'). A 'practicing Gandhian' and an 'action sociologist', he is credited with pioneering a nationwide Sanitation Movement in India spanning more than five decades. Sulabh (originally known as Sulabh Shauchalaya Sansthan) was started by Dr. Pathak in 1970 with the aim of liberating manual scavengers in India from the dehumanizing work of cleaning the widely prevalent 'dry bucket toilets' in urban as well as rural areas. Towards this end, he is known for innovating the simple, affordable two-pit composting pour-flush toilet – popularly called Sulabh Shauchalaya - which has helped address the twin challenge of open defecation and manual scavenging. His efforts are known to have helped the liberation of more than 200,000 scavenger women, rehabilitating them through alternative employment and skill development, and restoring their dignity and rights, thereby ushering in a social revolution. Sulabh has been in the forefront of Government of India's flagship Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Campaign), building over 1.5 million two-pit pour-flush household toilets across the country. Another 54 million toilets have been built by the Government based on this design. Dr. Pathak is also credited with the innovation of 'pay and use' public toilets in India, started in 1974. The Sulabh toilet innovation has been recognized by the UN Centre for Human Settlements (UNCHS) as a 'Global Urban Best Practice'. Under Dr. Pathak's able leadership, his organization has further pioneered the Sulabh technology for biogas generation from human excreta at its public toilet complexes, and the Sulabh Effluent Treatment Technology which safely recycles the contaminated effluent from the biogas plant into a colorless, odorless and pathogen-free liquid that can be safely disposed or utilized for non-potable purposes. Sulabh's sanitation-related innovations have been replicated internationally in several countries in South and South-East Asia, Latin America and Africa. Dr. Pathak's multifarious and relentless efforts as above have brought him and his organization a record 98 awards and accolades nationally as well as internationally. Among the most notable ones are the Padma Bhushan in 1991, the International Saint Francis Prize for the Environment "Canticle of All Creatures" (conferred by Pope John Paul II) in 1992, the Stockholm Water Prize in 2009, the Legend of Planet Award (from French Senate) in 2013, and the International Gandhi Peace Prize in 2016. Given the unparalleled contributions of Dr. Pathak in the field of sanitation and public welfare, he can be truly regarded as a living legend in the field of sanitation on Planet Earth. However, while Dr. Pathak's exclusive contributions to societal well-being and equality through sanitation are widely recognized, little is known about him as a water crusader. He is equally credited with innovating drinking water interventions and approaches that are pathbreaking and unique and provide sustainable and affordable solutions for enabling universal realization of the human right to water. This photo story aims to throw light on this lesser known side of Dr. Pathak's contributions as an inspiring water leader. The title photo portrays Dr. Pathak at a welcome function in his honor at the Sulabh Sulabh Safe Drinking Water treatment plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal. He is seen posing with a 20 liters 'Sulabh Safe Drinking Water' jar, together with ladies from the local community, signifying that he stands for the cause of universal access to safe and affordable drinking water for all.

Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak explaining his water-related endeavors at Sulabh campus in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Dr. Pathak's efforts in relation to water comprises the innovative technologies for safe drinking water supply. He believes that the first target under SDG 6, which aims to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water, in turn reaffirms universal realization of the human right to water. However, this is a formidable challenge in many parts of the country due to widespread water quality problems. Worst to suffer are the low income and poor communities that have difficulties accessing clean contamination-free water at affordable prices. Consequently, in 2014 he pioneered a novel approach under the name of 'Sulabh Safe Drinking Water Project', implemented in areas having water quality problems. This project began in areas having good rainfall such as in W.B. where water is available in plenty from ponds, rivers and dug wells. These projects, implemented in partnership with a French organisation called '1001 Fontaines' and local organizations like farmer cooperatives and NGOs, treat the water drawn from such sources and provide onsite supply as well as home delivery at very nominal prices.

Severe keratosis in the palms of an arsenicosis patient in North 24 Parganas district, West Bengal

An important geogenic contaminant in groundwater is arsenic and more than 70 million in India are estimated to be at risk of exposure through drinking water. The permissible limit for arsenic in drinking water in India is 0.05 mg/l while the WHO standard is 0.01mg/l, bur in many areas, especially in the Ganga River basin, higher concentrations are found in groundwater. This exposes people to the health risk of 'arsenicosis', which is associated with serious complications in gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, respiratory tract and skin, and can lead to cancer, and finally death. The above photo shows one such seriously affected patient with keratosis where rough, dry nodules appear on the palms and feet, that may later get thickened and give rise to cracks and fissures. The disease has severe socio-economic implications, threatening to push the already poor families into deeper poverty traps. W.B. is the first-known and among the worst-hit States where about 5 million people are exposed to the risk of arsenic in groundwater, without sustainable and affordable options for mitigation. Other major contaminants in groundwater-based drinking water in India are fluoride, iron, nitrate and salinity. Also posing health risk is widespread microbial contamination in surface as well as groundwater. The Sulabh Safe Drinking Water Project aims to address these various kinds of water quality challenges, and W.B. has been the hub of this project.

A protected pond along with part of its water treatment facility at Sulabh Safe Drinking Water plant in arsenic-affected Madhusudankati village in North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

The Sulabh Safe Drinking Water technology innovated under Dr. Pathak's leadership produces drinking water of appropriate quality from locally available surface or groundwater resources. It is simple, appreciably low in cost to construct and maintain, and requires low level of skillsets for operation and maintenance, easily available at the community level. A surface water based Sulabh safe drinking water plant has been set up in North 24 Parganas district of W.B. at Madhusudankati village. This district has the largest number of arsenic-affected habitations in the state. The project is implemented in partnership with the local farmers' cooperative named 'Madhusudankati Samabay Krishi Unnayan Samity Ltd.' (MKSKUS) and based on a protected nature-based source in the form of a rainwater-fed drinking water pond. This water is purified using a combination of simple water treatment technologies. The photo above presents a view of the pond and the flocculation tanks where the pond water is first pre-treated.

A dugwell from where groundwater is treated to produce Sulabh Safe Drinking Water in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

An alternate form of the Sulabh safe water technology is based on the dugwell. In the safe drinking water plant installed in Paschim Medinipur district of W.B. at Panchberia village, water from shallow aquifers is first drawn from a dugwell as shown in the photo above. This water is later subject to similar purification processes as applicable to the pond-water system. Paschim Medinipur district is not affected by arsenic, fluoride or other kinds of common geogenic chemical contaminants. Instead, here microbiological contamination of shallow groundwater has been reported as a problem, leading to chronic diarrhea in the village and its neighborhood. The plant is installed in partnership with a local farmers' cooperative called Mehanati Kishan Samabay Krishi Unnayan Samity Ltd (MKSKUS) and operated by selected members of its Self-Help Groups (SHGs). In such areas where the groundwater is free of chemical contamination, but microbial contamination is the problem, dugwell emerges as a viable source of raw water.

Adding alum and bleaching powder to raw pond water as pre-treatment at the Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

In this simple community-based water treatment process, the first step is flocculation. The pumped water from the pond or dugwell is first received in flocculating tanks where alum and bleaching powder are added to the water and stirred mechanically using a rod fitted with propeller. This solution is allowed to settle for about eight hours. Alum (or Aluminum sulfate) reacts with bicarbonate alkalinities and other fine particles in the raw water to form a gelatinous precipitate which settles down. Bleaching powder (or Calcium hypochlorite) contains chlorine which helps disinfect the water.

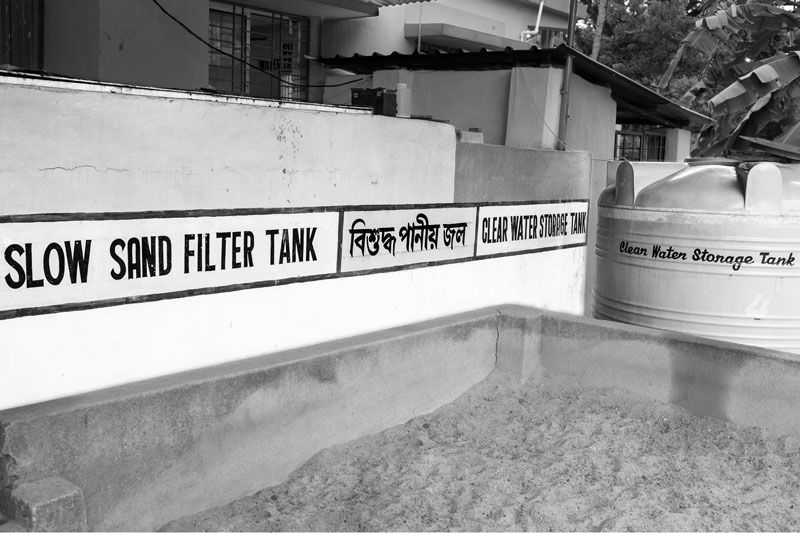

Outdoor filter beds where the supernatant water from flocculation tanks undergoes filtration – at Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

The supernatant water obtained from the flocculating tanks is passed through two filters located outdoors - slow sand filter (containing a sand and gravel bed) and activated carbon bed. These filters are shown in the above photo. The slow sand filter further removes turbidity and pathogenic organisms through various biological, physical and chemical processes, as well as any other large particles remaining in the water. The activated carbon bed helps remove any chlorine gained from the bleaching powder, thus eliminating unpleasant odors and tastes, and removing organic pollutants naturally present in the water. The filtered water emerging from the activated carbon bed is collected in a 'clear water tank' from where it enters the purification unit located indoors.

Indoor filtration unit comprising activated carbon filter (extreme right), four graded cartridge filters (middle), and finally UV filter (extreme left) at Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

Water from the clear water tank is further made to pass through a number of filters located indoors. First is an activated carbon filter which further removes any organic sources of unwanted taste and odors, pesticides or chlorine-containing compounds. This is followed by a series of graded cartridge filters. First is a 60µ cartridge filter membrane which serves as a prefilter helping protect the other three more advanced filter membranes from fouling by particles and other large impurities. The 10µ, 5µ and 1 µ membrane filters help with microfiltration, separating smaller suspended materials from the water. Finally, UV radiation is used for treating bacteria and viruses, thus disinfecting the water.

A 20 liters jar being thoroughly rinsed from inside at the Sulabh plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

According to Dr. Pathak, upkeep of quality of the water is of utmost importance in operating the Sulabh Safe Drinking Water projects. Therefore, before bottling, all water jars are first properly cleaned from outside and later rinsed and sterilized with chlorine solution from inside. While at the Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati, these processes are completely manual, at the Panchberia plant, there exists a semi-automatic bottle rinsing facility, as shown in the photo above.

Treated pure drinking water emerging from the UV filter being filled in 20 liters plastic jars at the Sulabh plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

The treated water emerging after UV radiation is safe for human consumption because it is free of pathogens. In case of pond-based technology, it is naturally free of arsenic, fluoride, iron or other geogenic chemical contaminants by virtue of being derived from rainwater. In both kinds of plants (pond- or dugwell-based), the treated water is filled into 20 liters plastic jars and plastic bottles of smaller capacities. A glimpse of the process of filling 20 liters jars is shown in the photo above. At this plant, everyday 8,000-10,000 liters treated water is produced. At the North 24 Parganas district plant, the daily production is 6,000 liters.

Chhaya Rani Mondal, from Gobardanga municipality, heading home with a 20 liters jar procured from the Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

Dr. Pathak's approach through the Sulabh Drinking Water project is to make clean contamination-free water accessible and affordable for the low income and poorer communities. Thus, treated safe drinking water is supplied at a nominal price around Re 0.50-0.60 per liter in the served villages, with rates varying between the different Sulabh safe drinking water projects. At this plant, a 20 liters jar may be procured on-site at a price of Rs. 12 (approx. 0.16 USD) as shown in the photo above. Arsenicosis patients, schools and ICDS childcare centers are supplied with the packaged safe drinking water free of cost.

Mrityunjay Bera, resident of Jot Govardhan village - carrying home a 20 liters jar procured from the Sulabh plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

At the drinking water plant in Paschim Medinipur district, a 20 liters jar costs only Rs. 10 when procured on-site. Many consumers regularly procure their water jars in person from the plant itself, as shown in the photo above. Apart from local households in Panchberia village itself, residents from five other neighboring villages benefit from the treated water produced at this plant against a nominal price. The treated water is also supplied free of cost to the village primary school, high school, primary health center and any families that suffer from diarrhea for the entire period until recovery.

A batch of packaged safe drinking water jars being loaded for home delivery at Sulabh plant in Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

Since Dr. Pathak has been concerned with the need of improving the physical accessibility of safe water for the poor deprived communities, he has supported the Sulabh Safe Drinking Water projects with vehicles for home delivery of the packaged water. One such vehicle is shown in the photo above. An additional charge for home delivery is levied which is also nominal. In this project, up to the first 4 kilometers are charged at the rate of Re. 1 per km, while beyond this a flat rate of Rs. 6 per jar is charged. At the drinking water plant in Paschim Medinipur district, home delivery is charged extra at a flat rate of Re. 1 per kilometer.

One liter and 500 ml bottles of treated drinking water produced at Sulabh plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

At the water plant in Paschim Medinipur district, smaller bottles of one liter, 500 ml and 250 ml capacity are also produced, as shown in the photo above. These bottles are supplied at local events such as festivals, marriage or meeting at affordable prices. For example, a carton having 100 bottles of 500 ml capacity costs merely Rs. 24 (0.33 USD), thus making one liter cost around as little as Rs. 8.32 (0.11 USD). At the plant in North 24 Parganas district, where packaging is done in one liter and 600 ml bottles, the cost is Rs. 10 and Rs. 6 respectively. Though cheap in price, the smaller bottles help generate substantial extra income.

Dr. Pathak trying his hand at fixing brand labels on packaged bottles at the automatic rinsing, filling and capping (RFC) unit in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

The Sulabh plant in Panchberia village has fully automated units – one for manufacture of smaller bottles and another for their rinsing, filling and capping (RFC). At this unit, all small bottles get automatically sanitized, filled up with the treated water, and thereafter capped before emerging outside where the brand labels are manually applied, as shown in the photo above.

A well-equipped water testing laboratory at Sulabh plant in Panchberia village, Paschim Medinipur district, W.B.

Given Dr. Pathak's priority on maintaining the quality of the supplied product, every Sulabh Safe Drinking Water plant has been provided a laboratory where the quality of the water produced and distributed is regularly monitored. The purpose is to ensure that people are always supplied drinking water that is safe from chemical and biological contaminants.

A local resident – Ganga Sutradhar – consuming Sulabh safe drinking water at home in Mirzapur village, Birbhum district, W.B.

A third Sulabh Safe Drinking Water Project has been installed in Birbhum district, W.B. at Mirzapur village. Here, access to safe drinking water is a challenge for the poor villagers because the water supplied through the local pipeline is perceived as unclean and drilling a personal handpump as an alternative is expensive. The Sulabh project here is run by a NGO called SEVA, and is based on water obtained from a large, protected pond. This water is subjected to the same treatment processes as related earlier. A 20 liter jar of Sulabh drinking water from the Mirzapur plant costs Rs. 12 when collected on-site and is used widely for domestic consumption as shown in the photo above.

Narendranath Biswas showing recovery from arsenicosis symptoms after regularly consuming Sulabh safe drinking water from the Madhusudankati plant, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

In Madhusudankati and three neighboring villages Bishnupur, Faridkati and Teghoria as well as one nearby municipality Gobardanga, 40 arsenicosis patients have been identified and eight men and two women have already died. Changing the drinking water source from the household handpump to Sulabh Safe Drinking Water has proved to be boon for these arsenicosis patients in the affected communities. As the arsenicosis patient Narendranath Biswas, aged 64 years, and resident of Gobardanga municipal area explains, drinking of Sulabh water over a long term has helped him recover markedly from the spotted melanosis on his chest and arms. Identified arsenicosis patients are provided with Sulabh water free of cost. Similarly, at the Paschim Medinipur Sulabh plant, several cases of recovery of families from chronic diarrhea are known, and there too, free Sulabh water is supplied to affected families until full recovery.

Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak explaining to Hon'ble Shri Sanjay Saraogi, Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) from Darbhanga, Bihar and Mrs. Saraogi about the Sulabh water treatment plant at Madhusudankati village, North 24 Parganas district, W.B.

Dr. Pathak's drinking water innovation receives visitors from far and wide. Many visit to learn about this unique yet simple, water-friendly and people-friendly approach to arsenic mitigation and supply of safe drinking water in general, with an intention of replicating the same in their own respective areas. The MLA from Darbhanga Hon'ble Shri Sanjay Saraogi expressed interest in this endeavor and came for a personal visit to the Madhusudankati water treatment plant in 2018. He plans to get a similar plant installed in Darbhanga to enable the people's access to safe and affordable drinking water in the city.

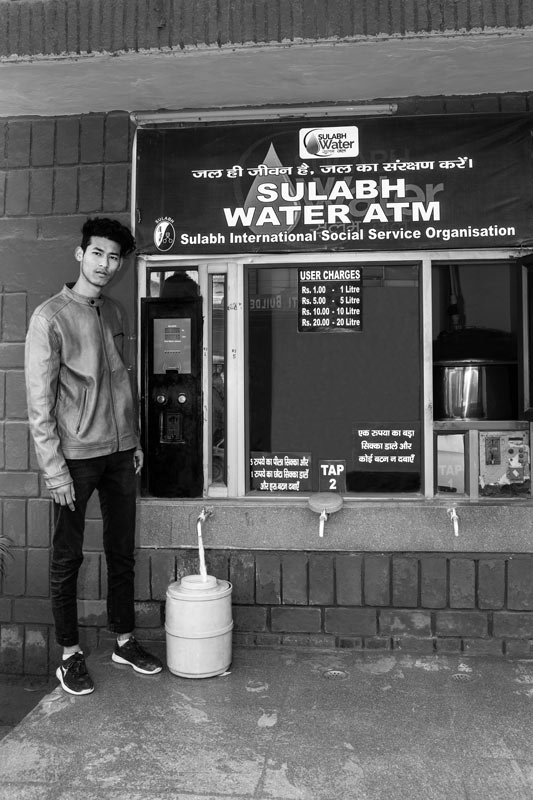

A local resident collecting safe drinking water from the Water ATM in Sulabh campus in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

In addition to the above projects, Sulabh Safe Drinking Water is also made available to the public through automatic water vending machines or dispensers at a nominal price of Re. 1 per liter. The aim is to enable equitable access to safe drinking water at an affordable price. At present there exist a total of 10 Sulabh ATMs working across four states and 13 new ones are proposed in two more states. All these operational ATMs purify water through the Reverse Osmosis (RO) technology and are connected to Sulabh Public Toilet Complexes. This facilitates re-use of the reject water emerging from these plants for flushing and cleaning the toilet complex as well as gardening in the campus. One such machine has been installed at the entrance of the Sulabh Campus in Delhi, as shown in the photo above.

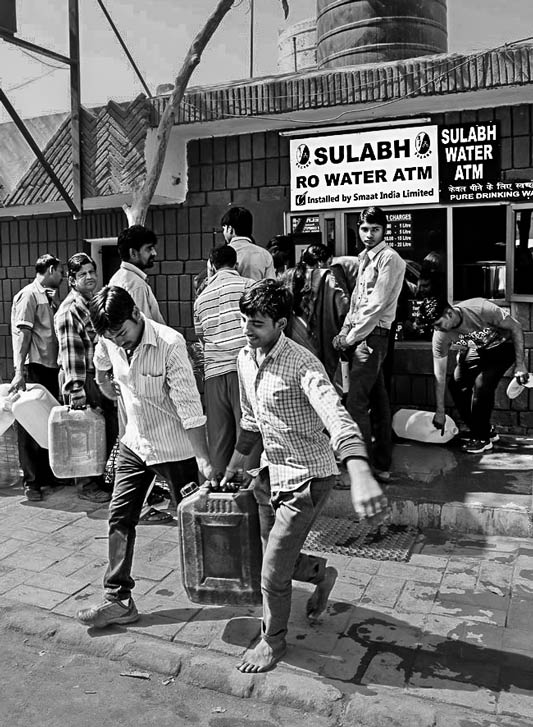

Local residents procuring safe drinking water from the Water ATM installed in Sulabh campus in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Though the facility at the ATM in the Sulabh Campus in Delhi can be availed by anyone, it is seen as a very welcome step for the low-income and poorer families living in the nearby localities who are ensured regular access to safe RO water at a very affordable price, which is otherwise a prerogative of the higher income groups. The ATM is based on RO technology with membrane filtration and is a part of Sulabh's mega toilet complex at this site. It produces 8000 liters of safe drinking water on a daily basis.

On the basis of the above account, Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak emerges as a water crusader who plays an inspiring yet challenging dual role as 'drinking water facilitator' and 'water savior'. In his first role, the primary concern is to enable universal access to safe and affordable drinking water, and hence enjoyment of the human right to water by all, while in the second role, he displays concern for closing the water cycle gap by minimizing wastage, promoting water re-use, and recharging groundwater to improve quantity as well as quality of water. Both these roles derive from the innovative Sulabh approaches for enabling access to safe drinking water which are "water-friendly" as well as "people-friendly".

The conventional role of drinking water facilitation is often seen as 'exploitative' of water resources where the concern is with drawing water from ground- or surface water sources and supplying it with or without treatment for human consumption, without much concern with protecting or augmenting the resource itself. However, Dr. Pathak's approach presents significant points of departure. The Sulabh Safe Drinking Water project approach is definitely water-friendly. His main emphasis - the pond-based safe drinking water technology - is an exclusive nature-based innovation rooted in the traditional wisdom of rainwater harvesting through ponds - an age-old practice in West Bengal. Harvesting rain in the pond benefits nature and the water resources by recharging the aquifers, thus lowering the concentration of arsenic or any other contaminant present in the groundwater through dilution in the long-term. Even dug-well is a water-friendly version because it extracts water from shallow aquifers within a high rainfall setting where the depleted layers get regularly recharged during monsoons.

Regarding the Sulabh drinking water ATMs based on RO technology, it can be said that while the technology per se is commonly seen as wasteful of water, what is important is the innovativeness of the Sulabh approach in using the RO technology. The Sulabh approach to drinking water ATMs transforms the discredited water wastage associated with the RO technology into a water-saving measure. Instead of allowing the reject water to be wasted by draining it away, it is turned into a valuable resource by connecting the ATMs to Sulabh Public Toilet Complexes and diverting the reject water for flushing, cleaning and other non-potable uses in the Complex. This reuse saves those precious volumes of freshwater which would have been otherwise extracted from ground- or surface water sources for fulfilling these essential water-related needs.

The Sulabh Safe Drinking Water technology are also people-friendly for a number of reasons. Central is their decentralized approach where the core water resource, the water treatment process and the manpower and management are all localized in the community. This decentralized approach imparts high credibility, efficiency, and sustainability which contrasts sharply with the centralized model of multi-village schemes based on river water supply through distantly placed mains. The second merit derives from simplicity of the treatment technology which makes it easy to use and maintain with little training. This has enabled efficient handling and maintenance by men and women from the local community, thus also generating local employment as well as social and gender empowerment. Third is the local availability and affordability of the components of the technology which eliminates run-down time and also keep the operational and maintenance costs low. Finally, Sulabh's innovative management approach of 'pay-and-use' enables financial sustenance of the project. Through a nominal payment of much less than one rupee (approx. 0.01 USD) per liter, perhaps among the lowest cost in the world, the consumers support the cost of the treatment process, labor cost of the caretaker staff, transport cost, etc. This ensures project sustainability on the one hand, and equitable safe drinking water access for all on the other, including the low-income and poor.

Thus, it emerges that in the process of producing safe drinking water at the local scale, Dr. Pathak shares an equal concern with safeguarding the water resources while obtaining safe water for consumptive use. This goes hand-in-hand with organizing water governance at the lowest possible level (local community), while engaging local women and men. Taken together, it can be said that Dr. Pathak's innovations are essentially "socio-technical" in nature and rooted in the approach of 'decentralized integrated water resources management', which is the way forward for achieving greater water sustainability in a world facing multifarious water challenges.

Dr. Pathak's innovations in the water sector, as described above, undoubtedly present an inspiring approach. By virtue of their twin merits as a means for ensuring safe drinking water provision and improving the sustainability of country's water resources, these play an important role in supporting progress towards the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Given these sustainability values, they offer great scope of upscaling and largescale adoption across different parts of the country. Besides West Bengal, ponds continue to be an important traditional source of drinking water across much of Peninsular and Western India where perennial rivers and streams are rare. However, the safety of their water quality is often doubtful, primarily on the basis of microbial parameters. The groundwater in many parts of these belts is contaminated, salinity and fluoride being the major complaints. Thus, safe drinking water access is an important challenge in these areas. Sulabh Safe Drinking Water project, particularly the rainwater-fed pond-based model has great potential to alleviate the water stress here. Similarly, the Sulabh ATMs have huge potentials to be adopted in a different setting – the multi-story apartment buildings in the emergent urban areas. These areas are often not adequately connected to municipal water supply resulting in challenges to enjoyment of the human right to water. In the absence of municipal water supply, people living in such apartment buildings may need to depend upon groundwater of compromised quality due to contamination with chemical and anthropogenic elements like salinity, fluoride and pathogens. Under such circumstances, Sulabh ATMs have a good scope of replication in these buildings to help purify the contaminated groundwater and also address water stress by providing the reject waters for re-use in flushing toilets, cleaning the complex, gardening and fulfilling other tertiary non-potable water needs.