Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Drinking Water Quality Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

29 November, 2016

Drinking water quality poses a serious challenge in contemporary India primarily due to widespread degradation of both surface and ground water resources. According to Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), water of around half of the country's rivers is unfit for human consumption. As many as 275 are found to have highly polluted stretches, with extremely high levels of biological oxygen demand (BOD) and coliform count, many lakes and ponds in the country presenting similar scenarios. According to Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), groundwater in more than half the country’s districts is contaminated. Groundwater in 276 districts in 20 states has high levels of fluoride while high levels of arsenic prevails in more than 39 districts in 8 states. High concentration of iron occurs in groundwater of 22 states and one union territory, while that of 113 districts in 15 states is poisoned with impermissible levels of hazardous heavy metals like lead, cadmium and chromium. Besides, the concentration of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) mainly from insecticides and pesticides like DDT, aldrin, dieldrin and heptachlor is on the rise at many places. Further, inland salinity in ground water is prevalent in arid and semi-arid regions in 10 states while increasing coastal salinity is recognized on both the coasts. With about 90% of drinking water supplies in the country derived from groundwater and the rest from surface water resources, this paints a scary picture, raising serious concerns about the health and wellbeing of rural and urban communities dependent on such contaminated sources. While the health impacts can be directly observed, exposure to such sources also brings a number of indirect impacts, such as social consequences of the health impacts and hardships in procuring safe water from alternate sources, if available. Both these direct and indirect impacts may be gender-differentiated since women, men and children can be affected differently. Access to safe drinking water is a basic human right, in turn being a fundamental precondition for enjoyment of several other human rights, most notably the rights to health, education, housing, life, work, culture and overall development. This photo story illustrates the challenges posed by degraded drinking water quality for rural and urban communities across the country. The title photo portrays drinking water containing excess of iron in Buxar district, Bihar. In this state, 19 districts are known to be affected by high levels of iron in groundwater. Water containing iron turns yellowish or reddish on standing and also possesses an undesirable metallic taste, often leading to its unsuitability for drinking.

A young lady debilitated by severe skeletal fluorosis due to consumption of fluoride-rich groundwater in a village in Nalgonda district, Telangana

In India the permissible limit of fluoride in drinking water is 1.5 mg/l but consumption of water with higher concentrations over extended periods exposes people to risks of dental, skeletal, and non-skeletal fluorosis. About 62 million people in the country are estimated to be suffering from various levels of fluorosis, of which 6 million are children below the age of 14. Telangana is second in the list of states associated with drinking water quality problems. Fluorosis is rampant in the state with 19,22,783 affected individuals. The worst hit is Nalgonda district where in the age group of 12-15, prevalence of dental fluorosis has been found to be as high as 71.5% and according to one survey, 10,000 persons were already crippled by skeletal fluorosis in 1992.

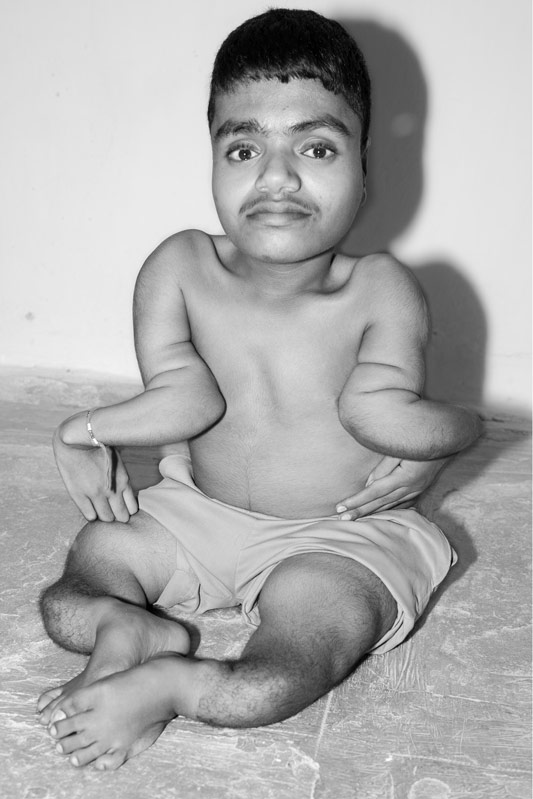

A young man handicapped by skeletal fluorosis due to long-term exposure to high fluoride in drinking water in Nalgonda district, Telangana

Skeletal fluorosis is a crippling disease which can affect both young and old & women and men alike. In younger people it can cause abnormal growth of bones at the joints, and twisting and deformities of skeletal bones as seen in the case of this young man, causing severe handicap. Such affected individuals can neither be educated and work, nor can they lead normal social lives. Moreover, for affected young women and even men, the propsects of marriage are dim.

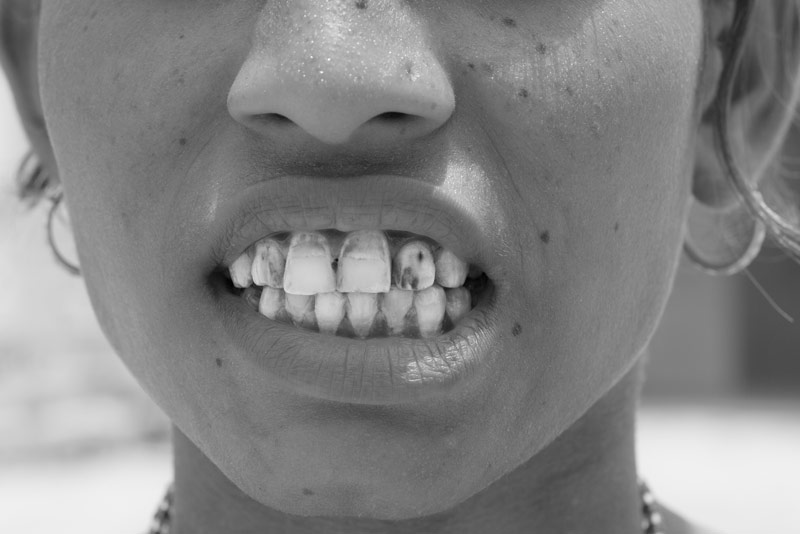

A girl affected by dental fluorosis in a village with fluoride-contaminated drinking water sources in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

According to recent government health estimates, Rajasthan is the worst affected state in relation to fluoride contamination with 30 districts having fluoride concentrations above permissible limit in the groundwater. The state has the highest number of affected habitations (7,670) with 48,84,613 people suffering from fluorosis. Dental fluorosis is a common occurence in the state, a condition known to have maximum prevalence in the 11-15 years age group with higher prevalence among boys than girls.

.jpg)

A middle-aged man affected by dental fluorosis due to drinking of fluoride-contaminated grounwater in Shivpuri district, Madhya Pradesh

Dental fluorosis is endemic in 14 states and 150,000 villages in India. Madhya Pradesh is known to have 1055 habitations affected by high fluoride in groundwater. Dental fluorosis is rampant in the affected habitations where common symptoms include chalky white patches on teeth separated by brown staining. Luster and enamel of the teeth may be completely lost and the teeth may have a corroded appearance in severe cases, also becoming pitted with brown, gray or black spots. As a final stage, the teeth may fall off. In the affected communities individuals of both genders as well as all ages who have had exposure to fluoride-rich drinking water through early years show clear symptoms of dental fluorosis.

A rural lady suffering from hyperkeratosis on the soles due to consumption of arsenic rich water in Buxar district, Bihar

In India, more than 70 million are exposed to health risks posed by high arsenic concentration in groundwater, largely within the Ganga river basin. The permissible limit for arsenic in drinking water in India is 0.05 mg/l, but in many areas in this belt, higher concentrations have been recorded which exposes people to the risk of arsenicosis. The problem was first identified in West Bengal where out of 19 districts, 14 are arsenic-affected with about 5 million population exposed to the health risk of arsenicosis. In Bihar, arsenic contamination is reported in groundwater from 17 districts, exposing more than 10 million people to the threat of arsenicosis.

Melano-keratosis in the hands of a lady dependent on arsenic-contaminated drinking water source in a village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

In arsenicosis the gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, respiratory tract and skin can be severely affected. Keratosis implies a symptom where rough, dry nodules appear on the palms and feet, which may later get thickened and also give rise to cracks and fissures, a condition referred to as hyperkeratosis. In melano-keratosis, dark pigmentation spots together with rough dry nodules appear on palms and soles. Arsenic is a carcinogenic element and cancer of lung, liver or urinary bladder can occur in arsenicosis patients. Arsenicosis may bring multifarious consequences for affected families and communities. Disease and death of especially the menfolk who are the primary breadwinners may push families into deep poverty traps. Simultaneously, affected villages may get socially ostracised as sending and bringing brides from such villages is often avoided. Sometimes, due to the fear of ostracism, affected individuals may not make their symptoms public and consequently delay medical attention, further aggravating the disease.

Handpumps producing 'unsafe' drinking water in a colony along the banks of Yamuna river in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

The handpump has been portrayed as a reliable source of safe water for decades but in this resettled colony in the heart of Delhi handpump is feared as a source of disease and suffering as drinking this water causes gastrointestinal problems. While every house has a handpump as its basic water source, the water is not potable due to contamination derived from the heavily polluted Yamuna river which flows close by. The river has high pathogen load and BOD levels due to release of large quantities of untreated sewage. Also untreated effluents from industries along its banks lead to high concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, zinc, mercury and cadmium. People have to drink the unsafe handpump water and bear the medical bills, or else struggle to get limited containers of safe water from the government supply tanker that visits occasionally. In the worst case scenario, they have to fetch safe water from alternate distant sources or spend money to buy bottled water from the market.

Carrying safe drinking water purchased from a Reverse Osmosis (RO) plant near Kolleru Lake in West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh

Kolleru is one of the largest freshwater lakes in India but ironically the residents of villages in and around it are deprived of access to safe water. Over the decades, the drinking water sources of these villages has been getting increasingly polluted. Not only is the lake water itself polluted but even the groundwater recharged through the lake is degraded. The water is saline, and contaminated with fertilizers, pesticides and POPs, mostly resulting from large scale paddy cultivation and aquaculture in the lake bed. In these circumstances, in order to safeguard their health, residents of the affected villages have little option than spending money in purchase and transportation of safe drinking water from RO plants.

Drinking supposedly ‘safe’ water amidst floods and livestock in Munger district, Bihar

Bihar is India's most flood-prone State, with about 22% of the flood affected population of the country living there. During floods, the hitherto safe water sources such as handpumps turn unsafe. When they get submerged under flood waters, they start producing water that may be contaminated with pathogens from human waste flowing in from toilet pits or open sewage drains and animal waste coming from fields and pastures. Also physical impurities and chemical contaminants from fields such as that from fertilizers and pesticides can get dissolved. In this photo, animals standing near the submerged handpump add to the pollution load of the water produced. In such situations, flood affected populations have little opportunities to procure real safe drinking water and the risk of epidemics such as cholera and diarrhea becomes high.

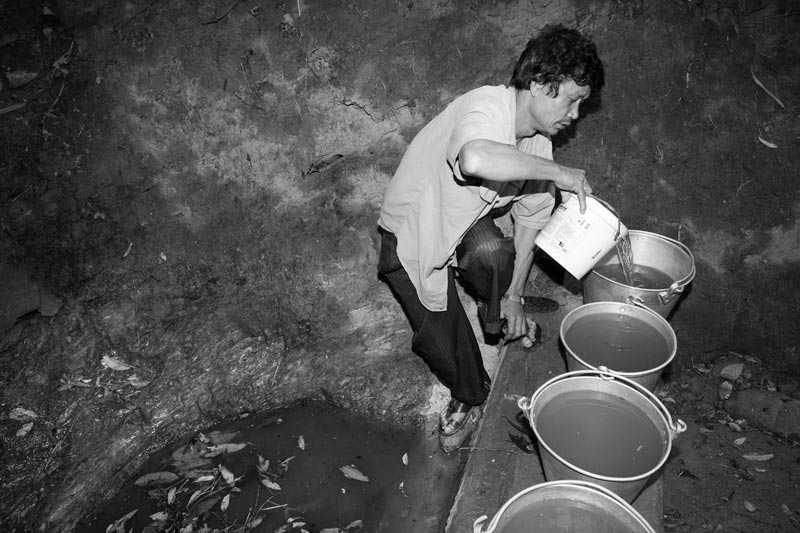

Collecting drinking water from an unprotected spring in Zunheboto district, Nagaland

In the hill state of Nagaland, procuring safe drinking water is a challenge for major part of the year. With villages located on hill tops, water is often collected from distant springs located down the hill. These water sources are often open and unprotected, therefore being prone to microbial as well as physical contamination. Moreover, the manner of water collection itself may expose the water to further degradation, since people walk into the water for collection. Consumption of such water exposes these hill populations to the risk of water-borne diseases.

Fetching ‘sweet’ water from a village pond in Kutch district, Gujarat

Gujarat is one of the worst placed states in the country in terms of groundwater quality, with high salinity as well as fluoride and nitrate concentrations above permissible limit. A majority of the 33 districts have areas with saline groundwater, making the local water sources non-potable. Kutch is one such district where groundwater in as many as 242 coastal villages is fully saline. Saline drinking water is objectionable in terms of taste and does not lead to quenching of thirst. In order to combat this problem, surface water supply schemes have been laid in many villages, but a number of villages still remain uncovered. Even in a number of ‘covered’ villages, water supply itself may be irregular. As a result, rural women and children may be forced to search for ‘sweet’ drinking water from alternate surface water sources, notably ponds. However, while pond water may be sweet in taste it may not necessarily be safe since ponds are open, shared by humans and animals alike, and also the drainage flowing into it may carry contaminants. Further, the water handling practice may not be hygienic since water is generally collected by physically entering the pond. All these factors can introduce microbial and chemical contamination in the drinking water collected, leading to prevalence of diarrhea and other diseases. Further, ponds may not be available in the vicinity and consequently, women and children may have to traverse long distances to procure drinking water. Carrying heavy loads of water over long distances can cause physical strains and spinal injuries. For children, stunted growth may be an additional outcome.

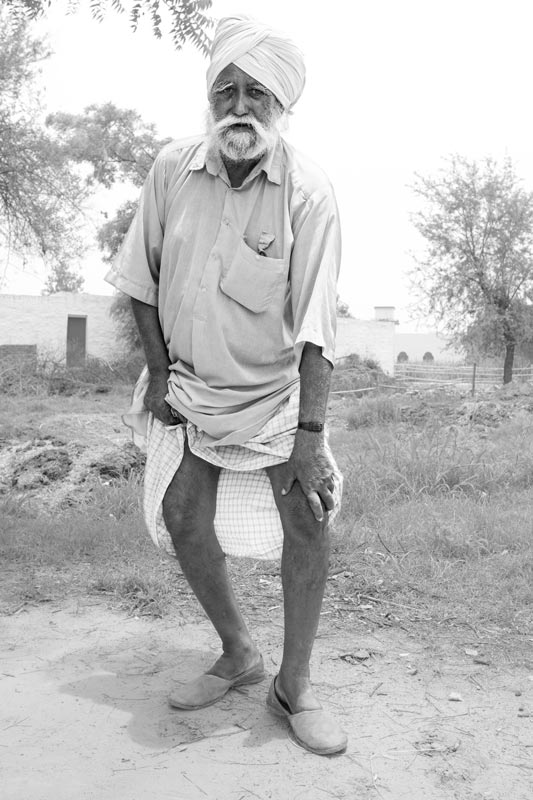

An old man suffering from joint pain in Bathinda district, Punjab. He lives in a village where all drinking water sources are highly contaminated.

Malwa region, the cotton growing belt in south-western Punjab, is facing severe challenge of deteriorating public health due to contaminated drinking water. Groundwater in the region is highly saline with high concentrations of fluoride, nitrate and POPs. POPs are a result of overuse of pesticides for boosting agriculture, the region's consumption being over 75% of that used in the whole state. Even the waters of Sutlej, Beas and Ghaggar rivers has been affected by pesticides. High levels of pesticide in drinking water is a cause of cancer and other serious health problems in the region, while high fluoride makes dental and skeletal fluorosis rampant. More than 15,000 cancer deaths during a period of 5 years was recorded in Malwa in 2013. In fact, a passenger train that plies from Bathinda to Bikaner everyday has 60% of its passengers as cancer patients who come from all across Punjab and go to Bikaner for cheap treatment. This train is locally referred as the ‘cancer train’.

Buying potable water from a tanker in a salinity and fluoride-affected suburb of Kolar city, Karnataka

According to government figures, more than 15 districts in Karnataka are affected by salinity in groundwater, high fluoride being an additional contaminant. Procuring safe and ‘sweet’ water in the affected communities is a challenge and people often need to buy drinking water from private tankers, causing much economic burden.

A rural handpump stained due to high levels of iron in the groundwater in South 24 Parganas district, West Bengal

Iron in groundwater beyond the permissible level of 1.0 mg/l is a common occurrence in India. It is a widespread problem in West Bengal, commonly co-existing with arsenic. According to CGWB, 15 districts in the state possess high levels of iron, often visible on and around handpumps and other drinking water sources as well as in containers that are used for transporting and storing groundwater for drinking. An excess of iron in drinking water can cause gastrointestinal irritation, stain teeth, gums and utensils, also promoting the growth of bacteria.

From the variety of contexts and scenarios presented in this photo story, it is amply clear that drinking water quality is a major challenge in India. Women, men and children may suffer directly through the debilitating impact on health, in turn jeopardizing their physical capabilities to work, study or enjoy social and cultural life, sometimes even resulting in death. The health impacts may be gender-differentiated, since women, men and children may show different levels of vulnerability and impacts. Becoming ill in general after consuming unsafe water may result in heavy medical expenses, loss of livelihoods, and absenteeism from school. Death of an adult member may lead an affected family into poverty and destitution. The option of using alternate safe water sources by members of affected communities too may not be entirely without risks and may cause indirect suffering. For instance, by carrying heavy water loads over long distances, women may get spinal and other kinds of physical injuries while children may suffer from stunted growth. Even men may confront accidents or get injured. Social consequences of exposure of communities and families to contaminated water are also noteworthy. It may thwart marriages and social exchanges. For instance, getting a bride in an affected village may be difficult due to the risk of exposure to debilitating clinical symptoms. In a nutshell, degraded water quality – whether microbial or chemical - can thwart the enjoyment of basic human rights in many different ways, and end up cumulatively pushing women, men and children into deep poverty traps and adverse social consequences. In order to safeguard health and various human rights of the residents in the rural and urban communities facing water quality challenges, there is an urgent need to find sustainable solutions for safe drinking water supply and also implement measures to arrest further degradation of the surface and groundwater resources.