Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Government Response to Rural Drinking Water Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

30 June, 2017

Women, men and children living in rural India encounter multifarious challenges in accessing adequate and safe drinking water as outlined in the story “Rural Drinking Water Challenges” dated 16 June 2017. In order to address these challenges, the government has initiated several interventions. The first and major one was started in 1972-73 as the Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme (ARWSP), succeeded by Swajaldhara in 2002 that promoted community participation in planning, implementation and management of schemes. ARWSP was revised in 2009 and merged with Swajaldhara as the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) which has a special focus on supporting rural water supply in water-stressed and water quality affected areas. As reported by the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS), Government of India (GoI) on 14.07.2016, out of a total of 1,714,528 rural habitations, 1,307,948 (76.15%) are “fully covered” (FC), 335,687 (19.58%) are “partially covered” (PC), while 70,893 (4.13%) are “quality affected” (QA). A FC habitation has 100% of the population with access to adequate quantity and quality of water, while a QA habitation has water quality problems due to contaminants like arsenic, fluoride, iron, nitrate and salinity. A PC habitation must meet national water quality standards even if it has <100% of the population covered. In addition, ‘coverage’ also means that a drinking water source should be able to supply at least 40 liters per capita per day (lpcd) and be located within 1600m in the plains and 100 meters elevation in hilly areas. The FC and PC together imply ‘coverage’ of 95.87% rural habitations with access to safe drinking water from an improved source, primarily tap, handpump, tubewell or covered well. In addition, recently the government has adopted a strategic shift towards piped water supply with an upgraded service level of at least 55 lpcd within premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not >100 metres. However, despite all the appreciable efforts, “slippage” is a significant problem primarily due to deteriorating source sustainability in terms of quality or quantity, or technical failures and operational hurdles. Slippage as well as non-existence of safe sources within close proximity of the residence prevents women, men and children from enjoying their human rights to water, health, education, livelihoods and overall socio-economic development, and significantly thwarts sustainable development of rural communities. This photo story aims to present critical reflections over governmental efforts at facilitating rural communities with access to adequate and safe drinking water in India. The title photo depicts a piped rural water supply plant in West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh.

A broken handpump in a village in Alwar district, Rajasthan

Handpump was the first and most important intervention in India towards expanding rural water supply coverage and providing ‘safe’ water to the rural masses. According to government figures dated 14.3.2016, 5,647,558 handpumps have been installed across different states of the country, at the rate of one handpump for a population of 250. Out of these 175,843 are reported to be non-functional. While handpumps have immensely helped ease the burden of drinking water collection for rural women and children who are the primary domestic water managers, and considerably improved the access to ‘safe’ water, unsustainability of handpumps on various grounds has emerged as an important concern. Due to poor maintenance of handpumps, many of these remain broken or dysfunctional for long periods. In several places, rapidly declining groundwater table has rendered these dry and hence inoperational. these problems again force women and children to resort to traversing long distances for procuring drinking water. In several other instances, degradation of the groundwater quality due to chemical contamination has rendered handpumps ‘unsafe’, spreading serious ailments like fluorosis and arsenicosis in rural communities.

A heavy-duty handpump perched on the Himalayan slopes near a village in Tehri Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

In Uttarakhand, access to drinking water is a significant problem, as with increasing deforestation, rising population and changing land use patterns, springs emerging on the Himalayan slopes that used to earlier supply drinking water to rural communities are drying up. To mitigate the problem, the government has installed handpumps along roads near villages. However, this is not a sustainable intervention. Not only are there quality problems with the water smelling of iron, but more importantly, the yield of these handpumps progressively decreases after the monsoon season. In the lean season, as the water table drops sharply, the pumping becomes increasingly harder, some of them ultimately drying up. This entirely defeats the purpose of the installation and the expenditure incurred in the process. The handpump shown in this photo is so 'heavy-duty' that even after combined pumping by two girls together, it barely yields a trickle of water.

A dysfunctional public standpoint under Ghogha rural drinking water supply project in Bhavnagar district, Gujarat

Gujarat is one of the states where attempts have been made since 1978 to improve rural drinking water access through individual- or regional piped water supply schemes. While the former are predominantly tubewell-based, the latter also depend upon distant surface water sources, primarily rivers and canals. One of the important regional rural water supply interventions is the Ghogha project in Bhavnagar district which serves 82 villages ‘covering’ an estimated population of 200,000 since 2007. It integrates dual water supply facilities with dependence on Narmada-based Mahi piped water system as well as local water resources including groundwater. Community participation through Pani Samitis or Village Water and Sanitation Committees (VWSCs) has been heralded as a hallmark of Ghogha project. However, despite the lofty claims made on paper about the success of Ghogha project, a field study in the project area has revealed that in reality, in many project villages, the piped water schemes are dysfunctional, with broken taps or inadequate water, even absence of water in the pipes at least in the summer season, and sometimes even supply of untreated contaminated water. Further, contrary to the hype, community level management of the village water supply systems with support from the state-level 'Water and Sanitation Management Organization' (WASMO) doesn’t seem to be working, with women and men even expressing ignorance about the existence and functioning of the VWSCs. According to CGWB, Bhavnagar is a district highly affected by salinity, fluoride, chloride and nitrate, and one of the reflections of the ineffectiveness of the Ghogha project lies in the rising number of cases of fluorosis and other ailments every year due to these contaminants.

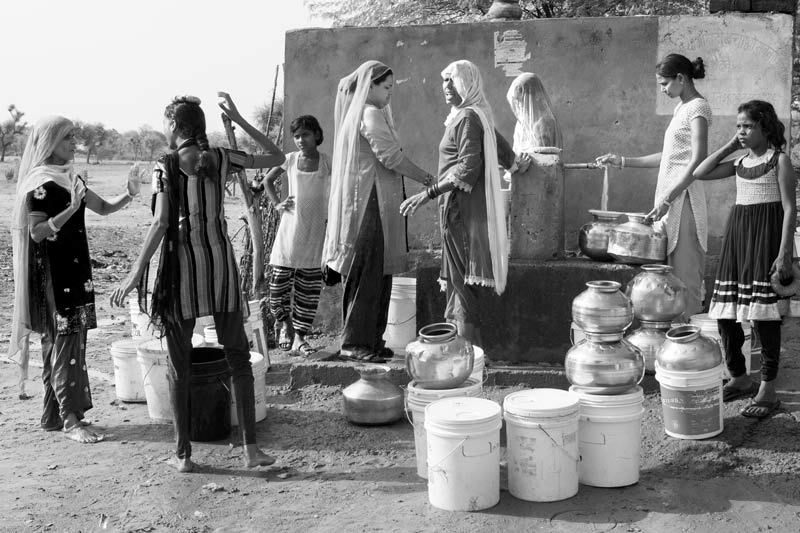

Fighting over water-filling turns at a public standpoint in a village in district Jaipur, Rajasthan

Many villages in Jaipur district have been provided with piped water supply from the Bisalpur Dam on Banas river. Indeed a great relief for the rural populace in this salinity and fluoride affected district, particularly the women and children responsible for domestic water procurement who used to travel far in search of good quality water. However, the benefits can accrue only if regularity and adequacy of the supply is maintained. The public standpoint shown in this photo is the single one in the village, and water is supplied for only an hour every day. This makes the quantity insufficient to fulfil the water needs of all the families dependent on it. This makes women and girls who come to fill their containers with water often end up shouting and fighting with each other over water-filling turns at the tap. In fact, this is not the story of just this village, but repeats itself in many others.

Waiting for the water trickle to fill the pitcher in a rural habitation in district Kolar, Karnataka

In Kolar district, the groundwater is overexploited, besides presenting water quality problems. The village depicted in this photo has very low water table, and high fluoride and salinity in the groundwater. Despite this reality, the piped water supply scheme is based on groundwater, with a number of public water points served by the same tubewell. Consequently, the pressure in the pipes is very low, and there is also irregularity of supply due to power cuts. This makes women wait endlessly for getting their containers filled with the trickling water. They may even need to return empty-handed since the supply duration is limited and containers to be filled are numerous. In case where the scheme fails to supply water due to technical faults, people have to even buy water from tankers. Further, due to quality problem, many members of the community suffer from symptoms of dental and skeletal fluorosis as the contaminated water is used for drinking and other domestic purposes. All these outcomes nullify the basic purpose of this rural piped water scheme, the story being similar in many other villages across the state and country.

An erstwhile Reverse Osmosis (RO) plant destroyed by a storm in district Bathinda, Punjab

Under the new strategy of the MDWS 2011-2022, both long- and short-term approaches are to be adopted for ensuring people’s access to safe drinking water in QA habitations. While the long term measure primarily comprises multi-village piped water supply schemes, community water purification plants in fluoride and arsenic affected as well as pesticide and fertilizer affected rural habitations is one of the short term interventions, with the objective of providing at least 8-10 lpcd drinking water per affected household. As a part of this new strategy, until December 2015, 7,368 community water purification plants, mostly using RO technology, have been installed in the states of Punjab, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh (M.P.) and Telangana. In Punjab alone 1,824 such plants have been installed. However, a recent field study in a number of worst-affected districts with fluoride, salinity, fertilizers and pesticides in groundwater in the Malwa region of the state revealed that a good number of these plants are either non-functional due to technical problems or are unable to deliver safe water due to technical limitations as the concentration of contaminants is much higher than the capacity these are designed for. Further, the quality of construction of these facilities is itself very poor as evident in this photo where a newly installed RO plant was entirely razed to the ground under the impact of a storm. As a result, the villagers are forced to drink contaminated water for months while the village continues to be counted as a ‘covered’ rural habitation.

The Maujampur multi-village rural water supply plant based on Ganges water in arsenic-affected Bhojpur district, Bihar

18 of the 38 districts of Bihar are affected by arsenic in groundwater, with Bhojpur as one of the worst affected districts. According to the state's health department, around 75,000 new cancer cases are detected annually in Bihar, of which the highest number is reported from the arsenic-affected districts. In order to combat the menace, a long-term arsenic mitigation strategy has been adopted by the state with surface water-based piped rural water supply schemes as the first approach. Since the arsenic-affected areas mostly lie close to Ganges river, a number of such schemes based on the river water are being executed. The first of these was executed at Maujampur village in Bhojpur district which is designed to supply 40 lpcd of arsenic-free water in 39 affected villages, through a daily supply for 2 hours. Here raw water drawn from the river is treated through conventional methods and then delivered to the villagers primarily through community standpoints. Designed for a life of 30 years, the plant was inaugurated in 2010.

The Maujampur rural water supply plant damaged by floods in river Ganges in arsenic-affected Bhojpur district, Bihar

Within a short span of 5-6 years of operation, the Maujampur plant already suffers from multiple malaises. While acceptability of the Ganges water is very high in Bihar villages, a field investigation revealed that inadequate power supply and untimely power cuts interrupt with timely operation of the plant. Also, the level of the main chamber containing the engine and pump is so low that a little rise in the Ganges water level risks its submergence. The 2013 flood in Ganges caused closure of the plant for a considerable period of time because, as seen in the photo, the raw water intake pipe from the river and other structures were broken and the main chamber was also partially submerged. It is well known that the Ganges bank on the side of Bhojpur district is flood-prone. Considering this reality, the plant required more robust and sustainable designing. Also, designing of the scheme including the capacity of the plant and the layout of the distribution network has been so poor that a number of tail-end villages do not get regular supply. In addition, the villagers report that the quality of the supplied water has deteriorated over the years. Inadequate functioning of the plant leaves the targeted users with little choice but switch back to their more reliable but 'poisoned' hand pumps.

A defunct handpump-attached arsenic treatment plant in a village in South-24 Parganas district, West Bengal

West Bengal (W.B.) was the first state in India where high arsenic in groundwater was detected in 1982, being much above the permissible limit of 0.05 mg/l, as per Indian standard. As a mitigation measure, more than 5000 community-based arsenic treatment units (ATU) have been installed by the government in the affected rural habitations, mostly as handpump-attached units. The photo shows one such ATU produced by Pal-Trockner that uses granular ferric oxide as the treatment media. However this technology, along with many others that were either imported or developed in India, became defunct in a few months after installation due to various technical and maintenance problems. The brown stains outside the ATU in this photo indicate the high concentration of iron in the groundwater alongside arsenic, which necessitates regular backwashing which is a cumbersome exercise for the users, besides the need of regular surveillance of water quality and change of spent media. Consequently, the ATU has been lying inoperational since long. After several decades, presently 778 rural habitations in 8 districts are reported as arsenic-affected, with more than 1.2 million population yet to be 'covered' with safe drinking water provision.

Treated piped water from the Ganges being used for cleaning vegetables in an arsenic affected village in South-24 Parganas district, West Bengal

Following the short-term mitigation approach involving installation of ATUs in arsenic-affected villages of W.B., the government also adopted a long-term approach based on supply of treated piped water from Ganges. However, as indicated by this photo, the piped water has been adopted by rural communities for various domestic uses such as washing, cleaning and bathing, but its acceptance for drinking purposes is extremely low. According to women and other users, the supplied water is often dirty, bearing soil particles, insects and other kinds of impurities, besides the strong smell of chlorine. These characteristics fail to match the local parameters of 'good-quality' water. The large surface-water based rural water supply scheme in arsenic-affected villages was installed mainly with the purpose of provision of safe drinking water for the people. However, in reality this water is being used practically for every purpose except drinking, thereby defeating the purpose, while women continue to draw drinking water from the contaminated handpumps at home.

A defunct fluoride removal plant based on the Nalgonda technique in a village in Nalgonda district, Telangana

Excess fluoride in groundwater is reported from 276 districts in 20 states in India. Nalgonda in Telangana is the worst hit district with 1,108 affected habitations, of which 484 habitations have concentration above 2.5 mg/l, the maximum permissible limit in India being 1.5 mg/l. Here high fluoride in groundwater was detected first in 1937, and despite implementation of several interventions by the state government, supported by the Centre, the situation remains grim. The various interventions include community defluoridation plants, domestic defluoridation units and surface water based rural piped drinking water supply. Despite the huge investments made, most of the community defluoridation plants are lying defunct. 15 of these are based on the Nalgonda technique, which are all lying defunct. Developed by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI), Nagpur, the Nalgonda technique requires addition of adequate lime and alum in the raw contaminated water, depending upon the fluoride content and alkalinity of the water. However, complexity of the technique, need for constant attention and lack of proper maintenance, besides a slow rate of water treatment have together led to failure of the community-level as well as domestic units. The Krishna and other surface water supply schemes in the district also show significant gaps, particularly in terms of non-regular supply due to infrastructure maintenance problems. As a result, people have to revert to fluoride-affected water supply, or buy treated water from RO plants, which may be sometimes distant and weigh heavy on the villagers’ pockets.

An ill-maintained community defluoridation unit in Shivpuri district, Madhya Pradesh

According to government figures dated 20.4.2016, 250 rural habitations in M.P. are affected by fluoride in groundwater which are yet to be ‘covered’ with access to safe water. In Shivpuri district fluoride in groundwater has been known since long and the first community defluoridation plant was installed by the government way back in 1985 in a village where cases of skeletal fluorosis were reported. However, the plant failed to provide relief to the affected population. Lack of cleanliness in the treatment tank, as seen in the photo, forced a number of women to reject its water for drinking, while others who wished to use it for drinking could not access the treated water regularly because of non-functioning of the plant due to irregularity of electricity. Consequently, the plant failed to mitigate the problem of fluoride contamination in the habitation, and provide safe water to the community. In this light, the question of effectiveness and sustainability of interventions implemented by the government for addressing rural drinking water quality challenges looms large, since mere installation of a technology is not the ultimate solution.

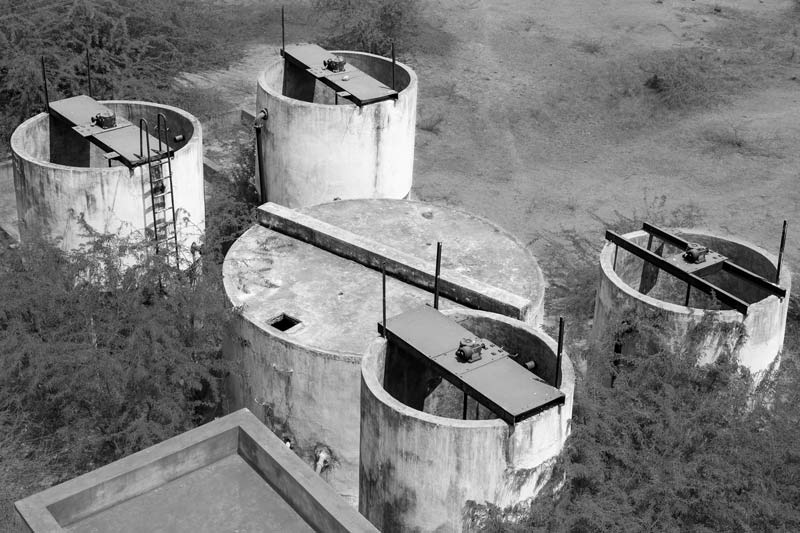

A tubewell supplying groundwater for a village-based ‘Pump and Tank’ scheme in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

In Rajasthan, two major kinds of piped water supply schemes are implemented by the government. The ‘Pump and Tank’ schemes are designed to cover one village, where water is supplied through electrically operated pumps from a tubewell to a central ground level reservoir located near the habitation, from where pipelines carry water to public standpoints or individual households. Groundwater is the common water source in such schemes. The other kind is the ‘Regional Water Supply Systems’ (RWSS) which are designed to cover more than one village, through piped connections to public standpoints or ground level reservoirs. The latter may be sourced from groundwater or canals, including the Indira Gandhi Canal. Though this intervention greatly reduces the drudgery of rural women and children in the semi-arid and arid settings of Rajasthan, water quality is a significant concern. According to recent figures, 21,234 rural habitations in the state are quality-affected, where groundwater contains excess salinity, fluoride, nitrate or iron. The tubewell shown in the photo pumps out groundwater to an open tank from which household connections have been taken. However, the water is contaminated with excess fluoride which is evidenced as dental fluorosis in children and joint pain in adults, the number of patients being on the rise. Despite the water quality problem, no short or long-term solutions have arrived in the village yet, while the village continues to be counted as ‘covered’.

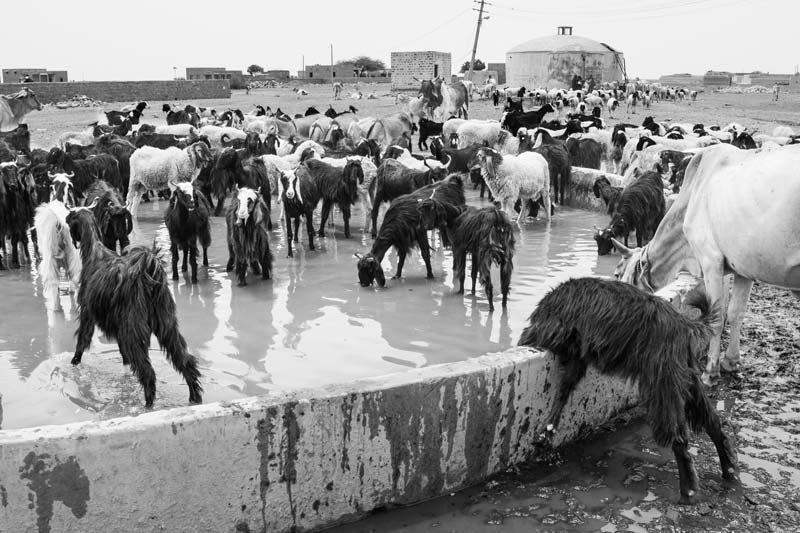

Animals drinking water supplied by the Indira Gandhi Canal under a multi-village rural water supply scheme in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

The Indira Gandhi Canal Project (officially known as the Indira Gandhi Nahar Project or IGNP) was inaugurated in 1987 with the purpose of diverting surplus waters of Ravi and Beas rivers in Punjab to the water-parched Thar Desert of Rajasthan, drinking water provision being one of the important components. The project area encompasses districts of Bikaner, Barmer, Churu, Hanumangarh, Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, and Sri Ganganagar, where rural communities thrive in areas having average annual rainfall as low as 136-328 mm. Undoubtedly IGNP has facilitated desert communities with access to drinking water close to home, with hundreds of rural habitations in the above districts connected to pipelines with large concrete water storage tanks and public standpoints. However, it has not stood the test on the front of quality aspirations of the people. While in many areas there is plenty of water in the system through a major part of the year, the rural communities have failed to adopt it for drinking as the first choice. The people find the water unfit for drinking since it is often dirty and smells foul. Consequently, women collect the IGNP supply water only for domestic purposes like washing, bathing and cleaning and it is utilized by animals for drinking purposes. For human consumption water continues to be procured from the traditional sources. Only when the alternate sources dry up completely, are they forced to use the IGNP water for drinking. Thus the rural habitations receiving IGNP water are counted as 'covered' only on paper, while in reality women and children in the desert communities continue with the drudgery of travelling long distances in the scorching heat to fetch drinking water from distant shallow wells (called beris) or even open ponds recharged by rainwater.

A spring-fed tank in the foothills providing rural drinking water supply in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

In Nagaland, more than 72% of the population resides in villages and drinking water access is a major problem for these communities. According to the census of 2011, about 35% of the rural households in the state procure drinking water from distant sources, carrying water loads up the steep hilly terrains since Naga villages are generally located on hilltops. As many as 20% rural households depend upon water sources like river, spring and pond. In order to address the plight of the rural population, one of the interventions supported by the government has been construction of tanks to hold the water discharged by underground springs. These tanks facilitate women and children by bringing water source nearer the village settlement for a few months during and after monsoons, which reduces their drudgery.

Scooping out water during the lean season from a dried up spring-fed tank in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

This photo depicts the same spring-fed tank shown before, presenting the situation when the spring discharge diminishes after the monsoon, leading to disappearance of the water, and consequently causing great hardships to the people. The spring discharge reduces drastically, necessitating scooping out the water with a mug, which makes water procurement a time-taking process. Moreover, even after the long-drawn exercise, the water collected may not be sufficient and the quality also be undermined.

Carrying drinking water home from filled tanks stored along the roadside in a village in Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra

According to recent government statistics, 466 rural habitations in Maharashtra are quality affected, of which 151 are affected by salinity. The village portrayed in the photo is salinity-affected, with no safe drinking water source. As a result people are dependent on weekly drinking water supply from government water tankers, which fill large tanks kept along the main motorable road near the village. Women have to carry water home manually in smaller containers as and when required. People often complain that the quality of the water delivered by the tanker does not reach up to their quality aspirations. Further, since these tanks lie in the open along the motorable road, the water is exposed to dust and other suspended particles that pollute the water. However, despite the quality limitations, in the absence of any other option, villagers are forced to use this water for drinking.

This photo story has presented a synopsis of the achievements and problems confronting the efforts made by government to address rural drinking water challenges in India. 82.7% rural households are reported as having access to safe water (from tap, tubewell or handpump) in the 2011 census. However, according to a more recent global report by WaterAid, the number of rural people in India lacking access to clean water is large, being 63.4 million, which is the biggest in the world. In addition to this figure, as revealed by this photo story, there are hundreds and thousands more who reside in ostensibly ‘covered’ rural habitations that are supposed to have been provided access to adequate and safe drinking water, but in reality they continue to suffer from drinking water challenges in various forms. This is because the government’s concern has been more with reaching physical targets and financial progress on paper, than ensuring real sustainable access to adequate and safe water on the ground. Starting from the First Five Year Plan (1951-1956) until the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012), government has spent more than Rs. 2,100 billion (approx. $32.5 billion) on rural drinking water, with more investments made under the Twelfth Plan (2012-2017). However, despite these huge investments and the rosy picture often painted, the reality of rural drinking water supply in India continues to remain gloomy, whether seen in terms of quantity, quality or sustainability. In areas with water stress as in Rajasthan, piped water supply has been provided since long but while these facilitate women and children with water access close to home, the problem of quality due to contaminated groundwater or untreated surface water negates the benefit. Other states like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana mirror similar situations. In Gujarat, piped water supply schemes are widespread such as the Ghogha project, but these may be non-functional or dry due to inadequacy of water or even supply surface water mixed with contaminated groundwater. Among other sources, handpumps and tubewells countrywide continue to remain inoperational for long due to technical faults or lack of water especially in summers due to receding water tables. Even the emphasis on community participation has failed to ‘fix’ these problems because the participatory process itself is ‘top-down’ involving mere delegation of responsibilities from the state government to the local government (Panchayat) bodies rather than true ‘bottom-up’ participation of the masses. Panchayat bodies do not actually represent people’s voice, but are merely elected political bodies that work as official village agencies. The result of missing out on people’s voice and perceptions with regard to drinking water schemes is evident from the outcomes of arsenic and fluoride mitigation projects in M.P., W.B. and Telangana. Adding to the problem are blanket approaches like the rural piped water supply agenda which looks attractive but may not be sustainable. Given the dwindling water resources of the country, where the average annual per capita availability has already declined to 1,545 cu.m./year (making India a “water-stressed” country), centralized multi-village piped water supply schemes dependent on far away surface water sources for the 900 million rural population appears to be quite an utopian idea, until realistic efforts rooted in the local context and knowledge are made to conserve and wisely manage the local water resources for drinking and other uses. If the ultimate motive is to enable rural women, men and children to enjoy their basic human rights through access to adequate and safe water, thereby enabling the 70% rural population of the country to march ahead on the path of sustainable development, it is essential that the government should wake up to the realities and rethink the strategy and processes adopted, moving towards a truly decentralized and integrated approach that rural communities can build, own and manage sustainably.