Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Impediments to Enjoyment of the Human Right to Water: An Insight on the 'Accessibility' Norm

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

28 January, 2020

Universal realization of the human right to water (HRW) can facilitate progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. This right, which entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use, can be realized if certain basic norms related to water are adhered. According to the UN framework on HRW, these include availability, quality and accessibility. The accessibility norm further comprises four overlapping dimensions, namely, physical accessibility, economic accessibility (or affordability), non-discrimination and information accessibility. The standards set up for implementing these various norms in India were elaborated in a previous story dated 16 April 2019. However, enjoyment of the right continues to face challenges in both rural and urban areas because one or more of the above-stated norms remain unfulfilled. This has been illustrated through a series of photo stories published between May and October 2019. Impediments to fulfilment of the water 'availability' and 'quality' norms were examined in previous stories dated 30 November and 28 December 2019 respectively. This photo story takes a look at the third norm, namely, 'accessibility', which lays down that water and water facilities and services have to be accessible to everyone without discrimination. This norm is extremely significant for India where according to the Census of 2011, about two-thirds rural households and one-third urban households lacked access to water within domestic premises. More recent figures from 2018, as stated in the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India's Report on the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP), show that populations living in as many as one-third rural habitations continue to traverse a distance of more than 100 meters to access a basic quantity of 40 liters per capita per day (lpcd). For those that lack physical access, affordability often becomes an additional challenge while women, children and other vulnerable or marginalized sections of population continue to bear the disproportionate burden of unequal water access. In this light, it is vital that the HRW norm regarding 'accessibility' is closely adhered. However, as will be discussed in this story, this norm remains blatantly unattained. Major impediments concerning physical accessibility include lack of adequate and safe water supply sources in or near habitations and at workplaces; poor operation and maintenance (O&M) of water supply systems; and irregularity of water supply. Economic accessibility is hindered by factors like the need to purchase water from private vendors in uncovered or quality-affected areas. The parameter of non-discrimination is impeded by factors like prevalence of strong patriarchy; parents' insensitivity of towards children's wellbeing; absence of safe water sources in schools; and overt and covert practice of social discrimination in different ways. Information accessibility is thwarted by absence of information, education and communication (IEC) regarding aspects like water quality, upkeep of community water sources, water supply disruptions, or avenues for complaint redressal with regard to water projects in operation. The title photo depicts the disproportionate burden borne by women and girls in fetching water from a distant source in the Thar Desert in Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan.

Accessing water at a river due to absence of adequate and regular water supply within the habitation in East Siang district, Arunachal Pradesh

Within the UN's normative framework on the HRW, physical accessibility is described as access to sufficient, safe and acceptable water within, or in the immediate vicinity, of the household. Also, the supply must be reliable and continuous, so that individuals can collect water at the times that they require. Accordingly, Government of India's (GoI) Strategic Plan, 2010-11 for drinking water security in rural India stipulates that by 2022, every household will be provided with access to 70 lpcd within the household premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not more than 50 meters. However, large-scale failures to meet the targets continue unabated. The CAG (2018) noted that only 77% rural habitations have been 'fully covered', while with respect to individual piped water supply (PWS) connections, GoI records (2019) reveal a coverage of a mere 18.3% rural households. This leaves millions without sufficient physical access to water for domestic and personal use, an instance of which is depicted in the photo above. This village has a spring-fed PWS but the water is insufficient and irregular, especially during the summer months, forcing women and girls to revert to the river located outside the habitation for accessing water.

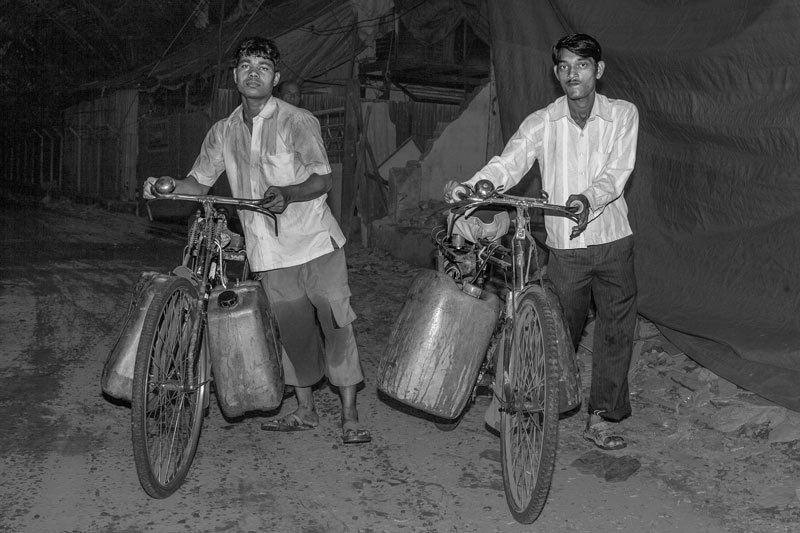

Fetching water from a distant source late in the night in a slum in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The situation in urban India is no different with regard to the physical accessibility norm. The GoI has laid down an urban service level benchmark (SLB) of 100% water supply at the household level but in reality, slums and informal colonies continue to remain excluded from public water supply networks on a large scale. Under the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), a target of providing water connections in 14 million urban households, including those in slums and informal colonies, by March 2020 was set. However, by 2019, an achievement of only 16.5% was reported. The above photo depicts the situation in a slum in Mumbai which lacks a proper water supply point, forcing the residents to travel to a far-off source where water is supplied late in the night. This photo was shot as late as 10 o'clock in the night.

Bringing the day's water ration from home due to lack of water source at a salt production site at Sambhar Lake in Jaipur district, Rajasthan

The norm of physical accessibility further requires sufficient, safe and acceptable water to be accessible within, or in the immediate vicinity, of each workplace. However, water provision at or near workplaces continues to remain neglected within public as well as private sectors in India. The above photo depicts the situation at Sambhar Salts Ltd. (SSL), a joint venture of the Hindustan Salts Ltd. (a GoI enterprise) and the state government of Rajasthan. Though this enterprise produces 196,000 tonnes of salt every year, the employers have not bothered to provide even a single water source for drinking and other personal uses for the employees. In order to survive through the day's heat amidst the huge salt deposits in the open, the employees have to carry water from home everyday.

A public handpump producing non-potable water in a rural habitation in Nainital district, Uttarakhand

The physical accessibility norm also stipulates that the water that is accessible within or in the immediate vicinity of the household or workplace must be 'safe' and 'acceptable' in terms of quality. However, in many of the 'quality-affected' habitations in India, potable water sources are absent. Further, in many cases, such as the one shown in the photo above, even the quality of the water provided is not monitored. In this habitation, and several others located about 2,000 m above the mean sea level in the Himalayas, handpumps have been installed along the roads for improved water access. However, as evident here, the water is enriched with iron, making it unusable for drinking or other domestic purposes. Consequently, women and children are forced to continue with the hardship of fetching water from distant spring sources located down the valleys.

A broken public handpump in a rural habitation in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka

Physical accessibility of water in India is further thwarted because of poor O&M of water supply systems. Lack of operational and well-maintained water sources make water unavailable to communities in required quantity on a continued basis. According to the CAG report on performance of the NRDWP (2018), underlying causes include deficiencies in undertaking O&M activities, non-utilization of allotted funds, and low involvement of local communities and village institutions in management and maintenance of drinking water supplies. Broken local water sources forces people to travel longer distances in search of alternatives and may end up increasing the burden manifold due to limited quantities available at alternate sources. The above photo presents glimpses of a broken handpump in the middle of a rural habitation that lacks even a handle. The residents report that the status has been so since long, and no attempts to repair it have ever been made.

An ill-maintained public water supply tank in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Poor O&M plagues the health of water supply infrastructure in urban areas alike, thwarting enjoyment of the HRW. In the urban slum depicted in the photo above, the tank is supposed to be filled by a municipal water tanker on a daily basis, providing water to the local residents through the attached standpoint. However, the standpoint has been lying damaged for a long time, disrupting water supply, thereby thwarting water accessibility in this marginalized urban locality.

A handpump rendered dry during summer season due to receding water table in Jaipur district, Rajasthan

In many parts of the country - rural and urban areas alike – physical access to reliable and continuous water supply is hindered by seasonal fluctuations in water availability, especially during the dry season. Examples include the mountainous areas where the spring-fed water supply systems in villages and towns dry up, and the arid and semi-arid belts where, as a result of overexploitation of groundwater, handpumps and groundwater-based water supply systems become all the more irregular in supply. The above photo depicts an instance where, every year during the summer months, this handpump dries up due to receding water table, rendering an otherwise 'fully covered' rural habitation 'partially covered', thwarting the water access of many inhabitants.

Lack of physical access to safe water during floods in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Physical accessibility to adequate and safe water in rural and urban India is also thwarted by natural calamities, drought and flood being the major culprits. Obviously, during droughts, irrespective of the source being surface- or groundwater-based, the water supply systems risk drying up. During floods, water is plentiful all around, but access to safe water in adequate quantities becomes a challenge because the safe water supply sources get inundated, an instance of which is shown in the photo above.

Extra economic burden imposed by purchase of water from a private tanker in an unserved slum in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The norm of economic accessibility (affordability) stipulates that water, and water facilities and services, must be affordable for all, so that the direct and indirect costs and charges associated with securing water do not compromise or threaten the realization of other human rights. States parties are further obliged to take steps to ensure that deprived urban areas, including informal settlements and slums, have access to properly maintained water facilities. despite the obligations and the lofty targets set up by the government, municipal water supply networks continue to remain missing in many urban slums in India, forcing residents to pay up manifold more compared to populations in the planned colonies. The photo above shows an instance from Mumbai where about 42% of the city's population resides in slums, of which only about 50% - which are classified as 'notified' slums - are served by municipal water supply. In the remaining, as the one shown here, people have a hard time procuring water from alternate sources, often incurring huge costs, forcing them to compromise other necessities of life like food and children's education.

Treated drinking water from a Reverse Osmosis (RO) plant being privately delivered for a price in a quality-affected village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

The affordability norm may also get challenged in habitations where the drinking water quality is degraded. According to government data from December 2018, there exist 61,635 rural habitations in India which are 'quality-affected', with groundwater-based sources containing excess of fluoride, arsenic, iron, salinity or nitrate. In Bihar, government statistics from 2019 show that 1.2 million population residing in 815 rural habitations are exposed to health risk from arsenic in groundwater. Several more are exposed to health risks from excess fluoride, iron and nitrate in groundwater. However, alternate safe water supply has not been provided universally. This places extra economic burden on the exposed families, because in many such affected habitations, safe drinking water is provided by private agencies against a price, as shown in the photo above. For the marginalized segments, this implies excess economic burden leading to compromise with other human rights.

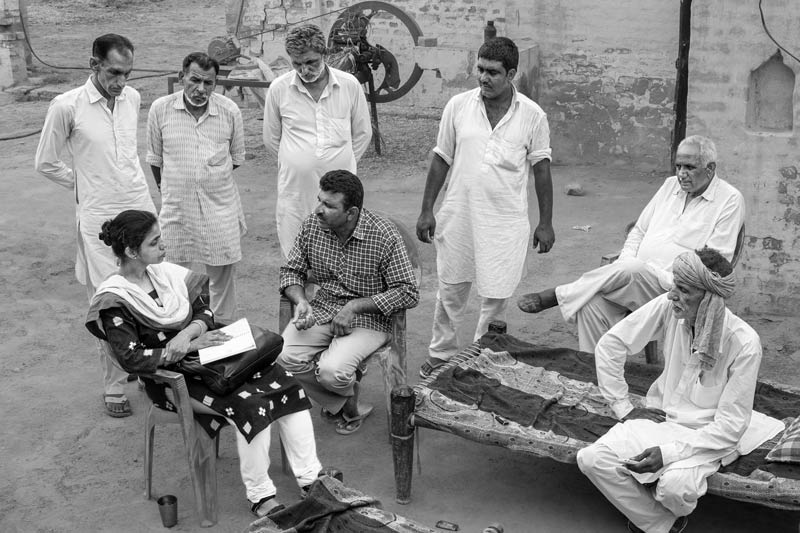

Women conspicuous by their absence at a focus group discussion on water with Nandita Singh, the lead author in a village in Fazilka district, Punjab

According to the norm of non-discrimination as described in the UN framework on HRW, water and water facilities and services must be accessible to all, including the most vulnerable or marginalized. States parties are obliged to give special attention to those individuals and groups who have traditionally faced difficulties in exercising this right, including women, children, minority groups and indigenous peoples. Regarding women, States parties should take steps to ensure that they are not excluded from decision-making processes concerning water resources and entitlements, and also that the disproportionate burden they bear in water collection is alleviated. However, despite formulation of statutory norms for enhancing women's participation in water governance, due to prevalence of strong patriarchy they continue to be excluded from water-related forums. The above photo exemplifies the problem where at a village-based focus group discussion on water problems organized by the authors, only men showed up, even when domestic water management is women's arena.

Children continuing to bear the burden of domestic water procurement in Kutch district, Gujarat

Under the UN framework on HRW, children have been identified as a group that has traditionally faced difficulties in exercising the HRW. States parties are obliged to take steps to ensure that they are not prevented from enjoying their human rights due to lack of adequate water in households or through the burden of collecting water. However, while on the one hand, as noted before, millions of rural and urban households in India continue to remain excluded from access to adequate and safe water, on the other hand, parents also lack the sensitivity towards children's welfare and instead end up engaging them in domestic water procurement, there existing no regulations to curb the practice. The above photo exemplifies the problem where instead of being sent to school, these young girls are sent by parents on multiple trips to a distant water source.

A student drinking arsenic-rich groundwater in a rural school in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Regarding children, States parties are also obliged to prevent discrimination against children and facilitate their enjoyment of the HRW through presence of adequate water in educational institutions. Further, as stipulated by the 'water quality' norm, the water must be of sufficient quality to protect their health. Therefore, all water provided in schools should be free from micro-organisms, chemical substances and radiological hazards that may constitute a threat to students' health. While drinking water sources are being increasingly provided in rural and urban schools, attention to the quality component remains weak, as exemplified by the photo above. It depicts the water situation in a school located in a village where groundwater has been found to be contaminated with high levels of arsenic, besides iron. Consumption of arsenic-rich water in school exposes children to the risk of developing the deadly condition of 'arsenicosis'.

Procuring water from a distant source located in the paddy fields in a tribal village in West Singhbhum district, Jharkhand

Within the UN framework on the HRW, the tribals (or indigenous peoples) have been recognized as a group that have traditionally faced difficulties in exercising the right, and States parties are obliged to take steps to remove any de facto discrimination against them and provide the necessary water facilities. As per 2011 Census, 36% of the over 2 million tribal households in India had their main drinking water source located more than 500 m from their house. Only about 15% had a source within the premises. Under NRDWP, 10% of the total allocation of funds is earmarked to be used for the supply of drinking water to tribal dominated habitations, and states are directed to take special care towards this end. However, the progress lags significantly and a sizeable proportion of tribal dominated habitations continue to remain unserved. The tribal village depicted in the photo above lacks even a single public water supply source inside the habitation, and the women and girls have little option but to traverse a long distance from the habitation down to their paddy fields where water is collected from shallow wells recharged by underground springs.

A public handpump appropriated and controlled by a powerful member of an upper caste in a village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

As stated above, according to the UN framework on the HRW, States parties have a special obligation to provide those who do not have sufficient means with the necessary water and water facilities and to prevent any discrimination in access to these on grounds such as civil, political, social or other status. Social equality is a core Constitutional principle in India and practice of inequality is unlawful. Nevertheless, at many places, public water sources directed for the welfare of underprivileged segments are misappropriated and taken under control by the socio-economically powerful groups, an instance of which is depicted in the above photo. Here, a public handpump which was installed with the target of benefiting the poorer scheduled caste communities residing nearby has been taken control of by a powerful individual belonging to an upper caste, and the targeted beneficiaries are forbidden to draw water from it.

Procuring contaminated drinking water in the absence of appropriate water quality information in Nainital district, Uttarakhand

According to the UN framework on the HRW, the norm of accessibility includes the right to seek, receive and impart information concerning water issues. The framework obliges the State parties to give full and equal access to all individuals and groups to information concerning water, water services and the environment which is held by public authorities or third parties. In India, IEC has been incorporated into rural and urban water supply programs. Within the NRDWP, the stated aim is to create awareness among rural people on all aspects of rural water supply and its related issues and to enhance the capacities of local institutions for planning, implementation and O&M of rural water supply systems. However, as also noted by the CAG report on performance of the program, there is large-scale non-utilization of related funds and shortfalls in achievement of IEC targets because proper planning and implementation of IEC is weak. The above photo shows a situation where a local spring-based water source (called 'naula') is contaminated due to wastewater discharge in the vicinity, but many of the unaware users continue to take its water for drinking due to absence of displayed information about the water quality status.

Unhygienic conditions at a rural drinking water source in East Siang district, Arunachal Pradesh

Contrary to the requirements under the norm of information accessibility and the scope and role of IEC defined within NRDWP, IEC activities continue to remain weak. As evident from the above photo, people of the village where this PWS is located appear to be quite unaware of hygienic practices for proper upkeep of their water source. From the same source where pigs are allowed to roam freely, drinking water is collected by the people. In the following photo below, children are seen as using water at the same site. The villagers do not seem to recall any training or educational sessions regarding hygienic upkeep of their drinking water source.

Children using the same unhygienically maintained water source shown earlier in East Siang district, Arunachal Pradesh

Pots left behind in uncertainty after an uninformed long wait for water at a community standpoint near Kolleru Lake, Andhra Pradesh

Apart from lack of IEC for building user capacities at planning, implementing and maintaining water supply systems, there is also commonly an absence of information regarding water supply routines in villages and cities, including any planned disruptions or irregularities. This is equally true of public standpoints and individual connections, especially in rural habitations and urban slums, which are already exposed to much inequity in water distribution. Absence of information about supply routines makes people wait in uncertainty, wasting productive time, also missing possible opportunities of water procurement from alternate sources. The photo above shows the situation at a public standpoint where people have left behind their pots in despair since water did not arrive at the announced time, and no information was dissipated regarding the changed routine.

A completed water supply facility that lacks public information about complaint redressal in case of operational disruptions in Kutch district, Gujarat

Another impediment to information accessibility concerns the lack of public information about complaint redressal mechanisms. Many water supply projects are completed without giving proper information to the public about the authorities to be contacted in the event of supply disruptions, leakage, breakage, or any other eventuality. The photo above depicts the situation in a village where a water supply project has been completed but the water supply often remains disrupted. However, no information is available to the public about who to approach or contact in case of any problems in its operation. In the absence of such information, the villagers are unable to approach the right authority for redressal of their complaints, and consequently, enjoyment of their HRW remains thwarted.

This photo story has illustrated the impediments to fulfilment of the 'accessibility' norm in India - the third and most elaborately stated norm for enabling realization of the HRW. The four overlapping dimensions of this norm, namely, 'physical accessibility', 'economic accessibility' (affordability), 'non-discrimination', and 'information accessibility' have been laid down in detail in the General Comment (GC) No. 15 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2002). Attainment of the different dimensions of the accessibility norm is impeded by multiple factors in India. The norm of 'physical accessibility' continues to be significantly unreached in both rural and urban India, because adequate, safe and continuous water supply in or near the habitation or at workplaces still remains to be provided in many cases. Either the coverage itself is inadequate, or else the lack of operation and maintenance (O&M) renders existing water supply systems defunct, or in some cases, seasonal inadequacy of water or natural calamities makes them inoperational for at least part of the year. Thwarting of the physical accessibility norm leads to a whole complex of problems with continuation of the drudgery of women and children as the primary domestic water managers, along with loss of valuable economically productive time, educational and developmental time for children, and ill-health and its associated costs. The norm of 'economic accessibility' is especially important for the socio-economically marginalized segments, for whom lack of physical access in terms of quantity as well as quality often increases the expenditure for water. This in turn forces many such households to compromise with fulfilment of their other basic human needs and enjoyment of other human rights.

On the basis of the empirical findings presented by the authors in this and several previous stories on the HRW from rural and urban India, it clearly emerges that fulfilment of the physical and economic accessibility norms is an inherent challenge facing the socio-economically marginalized sections to a greater extent than any others. Persistence of the impediments to these two above-stated norms is itself an illustration of the continuation of social discrimination in an overt or covert form, thereby further impeding the 'non-discrimination' norm. Additional impediments to the norm of 'non-discrimination' arise from factors like persistence of strong patriarchy, parents' insensitivity towards children's welfare, absence of safe water supply in schools, indifferent agency attitudes towards service provision in tribal and other marginalized habitations, and practice of social discrimination within communities. 'Information accessibility' appears to be the most weakly developed norm in the water supply sector in the country, and there is large-scale absence of IEC about water quality status, other essential aspects like irregularity or disruptions in water supply, and details about water supply projects which could enhance community participation in project monitoring and accountability. As a result of poor IEC, enhanced awareness and sustained behavioral changes that can lead towards improved human health, sustainable water use practices, greater transparency in the water sector, and the like, remain unachievable. The various impediments illustrated in this photo story are not exclusive to the specific contexts in which they are presented here but are universally valid for rural and urban settlements across India. It is high time that the fallouts of the continuing impediments to attainment of the 'accessibility' norms underlying enjoyment of the HRW are taken cognizance of and corrective actions applied by the responsible authorities. Otherwise, as an important precondition for reaching the SDGs, absence of universal realization of the HRW will continue to thwart achievement of the SDGs, particularly SDG 6 (access to clean water and sanitation) and also others including 3 (good health and well-being), 4 (quality education), 5 (gender equality), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 11 (sustainable cities and communities). This would all the more be important under the climate change regime which enhances stress on the possibilities of access to adequate, safe and affordable water in the country.

<