Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Impediments to Enjoyment of the Human Right to Water: An Insight on the 'Availability' Norm

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

30 November, 2019

The human right to water is an important instrument for reaching the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. This right entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. For enabling enjoyment of the right, a number of basic norms related to water, have been laid down under the UN framework. These include availability, quality, physical accessibility, affordability, non-discrimination and information accessibility. The status of enjoyment of the human right to water in rural and urban India, presented in a series of photo stories published between May and October 2019, illustrate that enjoyment of the right gets seriously challenged because one or more of the above-stated norms remain unfulfilled. But what are the factors that impede fulfilment of these norms? This photo story aims to provide an insight on the impediments facing attainment of the first norm, namely, water 'availability'. This norm lays down that water supply for each person must be sufficient and continuous for personal and domestic uses, which include drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, personal and household hygiene. Detailed analysis of the varied situations presented in the previous photo stories about the status of human right to water in India and observations made by the authors elsewhere in the country show that problem with fulfilment of this norm occurs under situations. The first is the absence of 'coverage' under water supply schemes. For example, in rural India, households in more than 23% habitations lack coverage with even a basic supply of 40 litres per capita per day, as per a Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India Report (2018). The second situation confronts that majority of habitations which are ostensibly 'covered' but fail to enjoy access to sufficient and continuous water supply. This can result from a number of factors. First and foremost, the operation and maintenance (O&M) of the water supply systems in place presents challenges. In some cases, operation of installed water supply systems is irregular, while in many other cases, water supply systems remain defunct due to lack of timely maintenance. Second, in many places, water supply is inadequate due to scarcity of the resource itself. Third, at many places valuable potable water gets wasted through leakages or other forms of negligence. Fourth, the resource scarcity may be reinforced by gross neglect of the existing local drinking water sources, in favor of dependence on distant sources. Fifth, sometimes water supply plans and projects are just not executed or come to be executed in a faulty manner. Sixth, laws, rules and regulations concerning water and water supply may come to be knowingly flouted, generally in a situation of inequitable distribution. Finally, there may be too many seekers from a single water source, forcing many to remain underserved or unserved. This photo story will explore in depth each of the above stated impediments. The title photo depicts a defunct handpump in a colony in Mumbai, Maharashtra, illustrating the first factor – absence of timely maintenance of water supply systems.

A broken handpump awaiting maintenance for months in a village in Patna district, Bihar

Operation and maintenance (O&M) of water supply systems is essential for water availability. Recognizing this importance, a detailed O&M manual has been developed by the Government of India (2013), but problems with O&M continue to count as one of the most outstanding factors thwarting water availability in rural and urban settlements in India. While preventive/routine maintenance is almost never organized, breakdown maintenance itself is often delayed and qualitatively deficient. Public handpump is the primary water source for about 54 million rural and urban households (Census 2011) but these are subject to frequent breakdowns. Their maintenance, however, is often delayed or inadequate, thwarting water availability to dependent populations. An extreme case is depicted in the photo above where the handpump has been rendered unusable for months not only because important parts have gone missing, but the main 'riser' pipe itself is broken, making the pump come off.

A public standpoint lying defunct since long due to lack of maintenance in Bhavnagar district, Gujarat

In the case of piped water supply schemes, the situation is no different. Even though these are generally set up with huge investments, neither is the required routine maintenance carried out nor breakdown maintenance taken up in a timely manner. The photo shown above depicts an instance from a coveted piped water supply scheme in rural Gujarat – the Ghogha project - which promised to bring drinking water to 82 villages in sufficient quantities round the year. It was also designed as a pioneer community-managed project where the local community was supposedly handed over the responsibility for O&M. However, as this photo attests, public standpoints soon became inoperational and the promised water became unavailable. At the standpoint depicted here, the main pipe bringing water to the taps got rusted and broke and was never came to be replaced. Defunct piped water supply points are an equally common site in urban areas, especially in the slums and poorer neighborhoods.

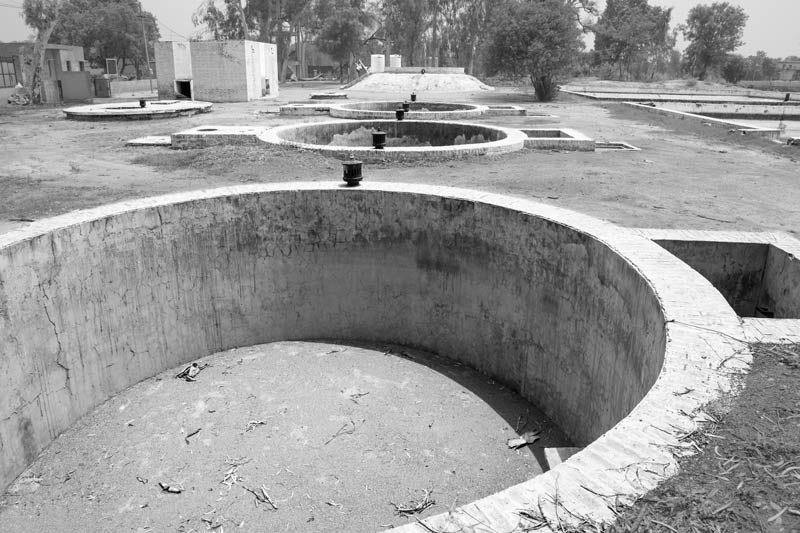

The water treatment unit of a rural water works lying idle due to lack of maintenance in Bathinda district, Punjab

Not only is there a problem with broken pipes, piped water supply schemes also become defunct due to absence of maintenance of other vital parts. More than 80 million households in the country depend upon piped water supply from a treated source (Census 2011), which in most cases are public water supply schemes. However, as noted earlier, maintenance of public water supply schemes is often poor, which may end up rendering many of these non-operational (as seen before) or 'quasi-operational' as shown in the photo above. The waterworks depicted in this photo was installed in 1985 to treat water from an irrigation canal for domestic supply in the village. The unit was operational until 2004 when it was transferred to the local self-government – the Gram Panchayat. As long as it was operated by the government, regular maintenance of the filter was ensured, thereby ensuring availability of treated water in the village. However, the Gram Panchayat could not ensure the same reportedly due to lack of funds, and since then the villagers have been provided with direct supply of the untreated canal water through the piped water network, thwarting the availability of safe drinking water. Sometimes, even this is thwarted when the pumps remain out of order for several days.

An irregularly operated tubewell-based rural water supply scheme in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Non-availability of water can also be a result of the failure to operate existing water supply schemes in a regular and timely manner. The CAG Performance Audit Report (2018) found that even after an expenditure of Rs. 619 million (approx. 8.7 million USD), 34 rural water works could not be operated due to factors like lack of power connection, damaged pipelines, leakages and non-execution of work as per approved specifications. Based on the authors' findings from case studies in the field, lack of manpower and technical faults in design may also be added. The photo shown above portrays a deep tubewell-based piped water scheme that was installed for safe water supply in the first arsenic-affected village identified in Bihar. However, irregular power supply prevents regular operation of the tubewell, leaving the people with no option but to consume arsenic-contaminated water from their shallow handpumps.

A surface water-based multi-village piped water scheme lying inoperational due to technical deficiencies in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Sometimes water supply schemes are installed at huge cost with much promise but without adequate exploration of their technical viability. For making safe water available in 39 arsenic-affected villages in Bhojpur district that lie close to river Ganges, a multi-village piped water supply scheme sourced from the river was implemented in 2010, with water delivery primarily through community standpoints. However, this ambitious scheme suffers from critical technical weaknesses which continues to thwart safe water availability for the served populations. It is located too close to the river and level of the main chamber containing the engine and pump is low. As a result, a little rise in the river water level risks its submergence, leading to closure of the plant. During occasions of severe flood, the unit also gets damaged which brings even longer run-down periods. Besides, inadequate power supply and untimely power cuts interrupt with timely operation, adding to the technical difficulties. The photo above shows one of the occasions when submergence of the pump chamber forced closure of the water supply plant.

Narendra Singh Nehan - a temporary staff at a rural water works explaining problems in its regular operation in Nainital district, Uttarakhand

On certain other occasions, inadequacies regarding the manpower responsible for O&M of water supply schemes hinders water availability. There may be understaffing or lack of training and hence the lack of capacity to undertake efficient and timely O&M. There may also be a lack of adequate incentives to carry out the duties diligently. In the photo above, an employee working for a rural water supply scheme in the hills of Uttarakhand explains how irregular operation of this waterworks is a result of staff-related problems. Even after 20 years of employment, he continues to be 'temporary', facing job insecurity and is grossly under-paid with a meagre salary of Rs. 6,000 per month (approx. 83.76 USD), while his working time normally exceed 8 hours. There is no other incentive apart from the salary. Also, he has not been adequately trained for the job, which further brings limitations to his capability of handling complex O&M problems, making the water supply scheme inoperational for longer periods.

Water supply affected by inadequacy of water in Kaveri river in Tiruchirappalli district, Tamil Nadu

An increasingly important factor affecting availability of sufficient and continuous water supply is the inadequacy or scarcity of water as a resource. According to World Bank data, the per capita water availability in India has declined from 3,090 cu.m. (1962) to 1,117 cu.m. (2014) and there is projection of further rapid decline. Only about one-third of the average annual surface water resources in the country is utilizable and even this volume is shrinking due to multiple factors such as erratic rainfall, reduced drainage, and over-withdrawal of water for non-potable bulk uses like irrigation. Many piped water supply schemes dependent upon rivers are failing due to low water flows. Kaveri is a 802 km long river whose water sharing has been long disputed between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Even after the Supreme Court of India's 2018 decision to award 39% share to Karnataka, 55% to Tamil Nadu, and the rest divided between Kerala, Pondicherry and the environment, the problem of water availability in the recipient states is not solved, because of low water level in the river. In 2012, 2016 and again in 2019, the river almost dried up, causing huge drinking water shortage in the dependent towns and villages. The photo above depicts one such occasion.

Scanty water in Himayat Sagar Reservoir in Rangareddy district, Telangana

Water availability is also being adversely affected by drying up of lakes, tanks, and other kinds of natural and man-made reservoirs, which enabled flourishing of many important cities in the past. Many of these cities face a great water challenge today because of progressive drying up of these water bodies. Examples include Bhopal, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad and Jaipur. According to a recent study based on satellite images from June 2019, several lakes in the country responsible for water supply in their respective cities show large-scale reduction of their water-spread areas. Himayat Sagar – a reservoir constructed in 1927 by damming the Esi river with the intention of ensuring availability of drinking water to Hyderabad - the capital of Telangana, is suffering from low water level in recent years. Not only has rainfall been frequently deficient, but it is also contended that degradation of the catchment area due to deforestation, illegal encroachments and constructions prevent the reservoir from receiving any inflow. The photo above shows a substantially dried up bed of Himayat Sagar, which affects water availability in the city.

A dried-up public handpump in Shivpuri district, Madhya Pradesh

Besides surface water scarcity, rapid depletion of groundwater is a serious concern in India. According to NITI Aayog's recent report (2018), 21 major Indian cities face risk of running out of groundwater by 2020, affecting over 100 million people. As per an assessment by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) in 2017, the number of 'Over-Exploited' assessment units (with more than 100% groundwater extraction) in the country is increasing, being 1,186 out of a total of 6,881. Several more are 'Critical' (extraction level 90-100%) and 'Semi-critical' (extraction level 70-90%). Consequently, groundwater-based water supply sources in these areas face the perpetual risk of drying up seasonally or permanently. Thus, the water availability for many among the of 83 million households that depend upon handpumps and the 20.9 million households that depend upon tubewells (Census, 2011) is threatened. The dried up public handpump shown in the photo above lies in one of the 44 'semi-critical' areas in Madhya Pradesh.

A dried-up well in Shivpuri district, Madhya Pradesh

In the census of 2011, more than 27.2 million households reported dependence on wells as their main water source. However, with depleting groundwater resources and receding water tables, many wells especially in the over-exploited, critical and semi-critical areas are drying up, reducing water availability to the local communities. One such completely dried up well is shown in the photo above. Two major drivers behind receding water tables are withdrawal of groundwater in excess of the recharge and reduced recharge due to critical landscape changes, involving deforestation and reduced potential for infiltration.

A dried-up spring-fed tank thwarting water availability in a hill community in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

More than 1.3 million households in the country depend upon springs as their main water source (Census 2011), mostly in the hilly regions. At many places water flowing out from springs with high discharge can be collected directly while in case of the low discharge springs, the water is allowed to collect in tanks for withdrawal. Water availability through both kinds of spring-based water sources is getting thwarted as springs are increasingly drying up due to landscape changes that primarily involve deforestation for diverse purposes.

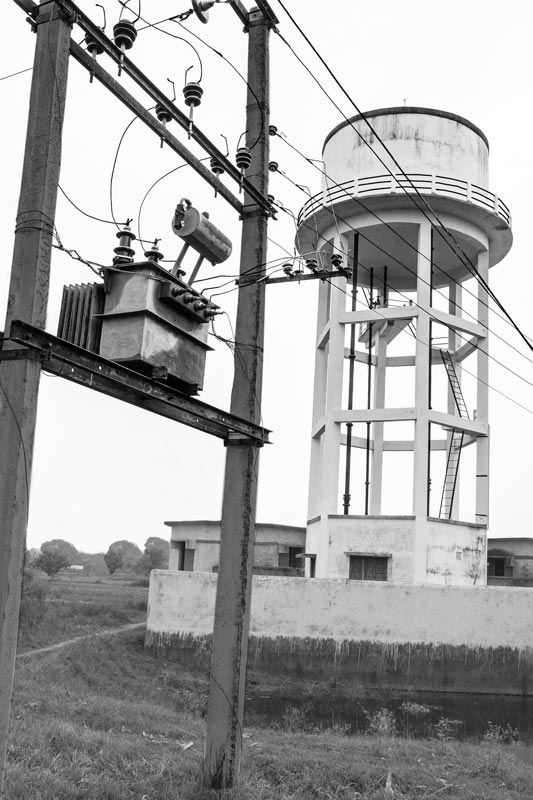

Dried up Ramgarh Lake and its non-working water works in Jaipur district, Rajasthan

Finally, water availability is affected by drying up of the sources feeding piped water supplies. These commonly include tubewells, or rivers, lakes and reservoirs. Over 107 million rural and urban households in India reported dependence on piped-water supply in the census of 2011. The water availability for many of these risks being threatened by drying up of the feeder water sources. The photo above depicts the case of drying up of Ramgarh Lake - the main water supply source for the capital city Jaipur. Spread over an area of 15.5 sq.km., it was completed in 1903 and started supplying water to the city in 1931. It even hosted the rowing events of the 1982 Asian Games. However, since 2000, the rivers feeding this lake have gone dry, leading to drying up of the lake itself. The identified causes include construction of anicuts and other kinds of encroachments ranging from farmhouses to education institutes in the catchment. As a result, Jaipur's water supply was affected, leading to diversion of water from the Bisalpur dam to the city amidst protests from the local residents who were dependent on the dam for irrigation and drinking.

Wastage of potable water from a massive pipeline leakage in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Another culprit reducing water availability for domestic and personal uses is water wastage from leakages in piped water networks. Leakages are often a result of lack of routine maintenance of pipelines and gain further quantum when their repair goes neglected. Leakages commonly reduce the overall water volume supplied and also lower the water pressure in the distribution system, thus affecting adequacy as well as continuity of supply. Water loss from leakages is substantial in India and estimated to range between 25–40% of the water produced by utilities in the main urban areas. The intensity of the problem is evident from the photo above.

Water wastage from a tapless public standpoint in a village in South 24-Parganas district, West Bengal

Wastage of potable water is another important cause underlying water deficiency. Sometimes water wastage is promoted by the infrastructure design such as when standpoints are erected with tapless pipes. On other occasions, if the taps get damaged or stolen, there is lack of timely replacement. As a result, water keeps flowing out from the pipe throughout the entire supply period. South 24-Parganas is an area severely affected by high arsenic in groundwater. As a mitigation measure, treated river water is provided to the affected villages through public standpoints. However, as shown in the photo above, a tap has not been provided for regulating the water flow, leading to gross wastage of the precious treated river water, thwarting water availability especially in the tail-end villages.

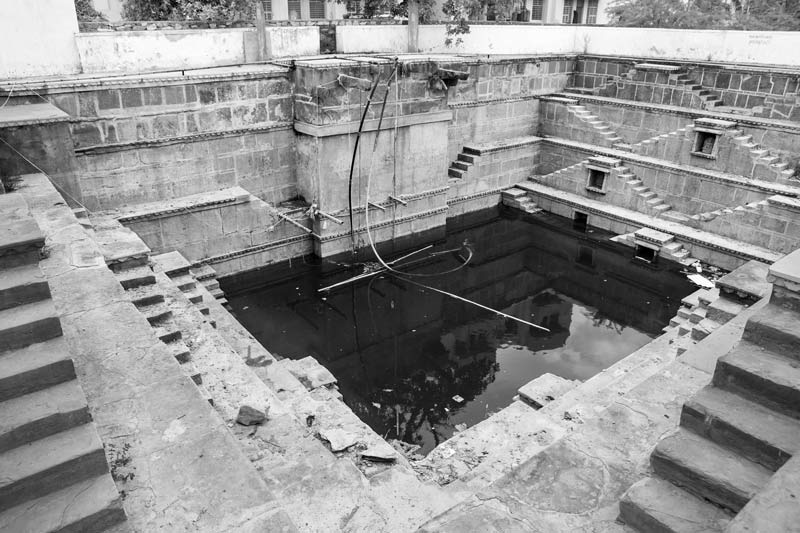

A neglected 'bauri' (step well) – a local water source – in a peri-urban locality in Udaipur, Rajasthan

There is a growing tendency in urban and rural areas of India to make water available for personal and domestic use through centralized pipeline networks. These often transfer water in bulk from distant sources, even when local safe sources are available and viable for fulfilling people's water needs sustainably. While this is projected as a sustainable solution for water security, it may actually bring risks of reduced water availability. Dependence on external sources soon leads to undervaluing of the local water sources, which are then neglected and become non-utilizable. Thus, under conditions of inadequate or intermittent supply from the external source due to factors like reduced water volume at the source itself or technical breakdown, water availability becomes a challenge despite the presence of old local water supply sources. The photo above shows a 'bauri' – a step well – in a peri-urban locality in Udaipur that was in use until recently. However, with the coming of piped water supply from the city, this local source has become neglected and unusable, even when the much-coveted piped water supply is erratic.

Sankey Tank – an erstwhile local drinking water source - in Bengaluru, Karnataka

In the semi-arid peninsular India - in states like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Telangana - surface and subsurface runoff has been harvested for centuries through a system of interconnected reservoirs – commonly called lakes and tanks. Developed in rural as well as urban areas, these served as irrigation as well as drinking water sources. In Bengaluru, where a major river is absent, such series of interconnected cascading tanks and lakes - were created over the centuries to cater to the local water needs. In the 1960s, their number was 920, and the city's water supplies were maintained from some of these. In the 1970s, the scheme to pump water from the Kaveri river 100 km away was begun, and gradually many of the tanks and lakes started getting encroached or converted into sewage tanks. The Sankey Tank shown in the photo above, was constructed in 1882 as a back-up water supply source for the city following the Great Famine of 1876–78. But after introduction of the Kaveri-based water supply, Sankey became neglected and attempts for encroachment made. Though in recent years, the lake has been rejuvenated, this is not to restore its identity as a drinking water source, but as a park and site of leisure activities. Today it stands in isolation from its chain, and its water quality as a significant concern.

Gadisar Lake – an erstwhile local drinking water source - in Jaisalmer, Rajasthan

Similar is the story of Gadisar Lake shown in the photo above, which was constructed as the main drinking water source for the city of Jaisalmer in the 14th century – a place receiving just about 200 mm average annual rainfall and lacking access to any perennial river. Women used to collect water from the lake which is said to have the capacity to retain water through 3 drought years, and if it ever dried up, there were about 100 wells located behind the embankment to draw water. However, after 1965, Gadisar came to be neglected as a drinking water source for the city, and piped water supply based on a distant tubewell was introduced. Later this was complemented with other distant sources including the Indira Gandhi Canal, taking away the possibility of city's dependence upon local water sources. Today, Gadisar is no more than a tourist attraction, with pollution, encroachment and ecological degradation, while the piped water supply received from outside is insufficient and qualitatively degraded.

A non-executed water supply scheme in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Non-execution or incomplete implementation of water supply plans and projects is another important impediment thwarting water availability in rural and urban communities. According to the CAG report (2018) mentioned before, poor execution, incomplete, abandoned or nonoperational works as well as unproductive expenditure brought a financial loss of over Rs. 22,120 million (approx. 309.1 million USD), besides depriving large populations from getting potable water even after lapse of several years. Some common causes noted are: non-execution of works by contractors, paucity of funds, lack of permissions/clearances from concerned authorities, land disputes, and non-availability of material. The photo above depicts the situation from the commercial capital of India – Mumbai – where in a locality settled by the primitive Warli tribe, the government started a borewell-based pipeline scheme with public standpoints. However, the scheme was never completed, the planned borewell never dug and the associated pipeline not laid. As a result, the Warli community at this location in Mumbai continue to suffer from lack of availability of adequate safe water for fulfilling their personal and domestic needs.

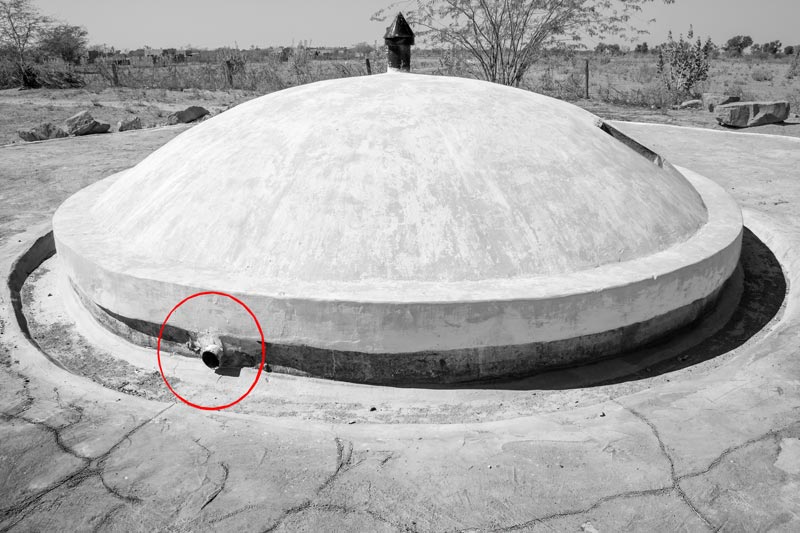

Faulty construction of a 'tanka' – an underground rainwater harvesting tank - in Jodhpur district, Rajasthan

Sometimes, water supply infrastructures are constructed in a faulty manner, without taking into consideration all technical details. The photo of the 'tanka' shown above is a case in point where an underground tank with capacity of harvesting 80,000 litres of rainwater was completed with an allocated fund of about Rs. 0.4 million (approx. 5,265 USD). However, the people report that the tank is unable to harvest rain adequately because the inlet pipe is located far above the ground level the where the water collects in the constructed catchment. Also, the quality of construction is substandard, and the cemented catchment as well as the underground tank have many cracks. As a result, the tank ends up losing even the little water that gets harvested. This and the above case speak of the lack of accountability underlying the State's commitment to make adequate and safe water available to the rural and urban communities.

Illegal tapping of water from a nearby supply mains in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Water availability for the rightful consumers also gets affected when laws, rules and regulations are violated. An important example is illegal extraction of water made from pipeline networks. In Mumbai, residents in many slum settlements that have been left unserved by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation and lack any alternate water sources, resort to illegally tapping water by connecting motors to the watermains passing nearby. This reduces the overall quantum of water in the pipes, makes the pressure drop, and consequently, reduces the water availability for the rightful served populations. In 2016, the municipality cracked the whip on 2,004 unauthorized water connections in the city, enabling the rightful water users to gain greater access. Such a situation is encountered in many urban centers in the country.

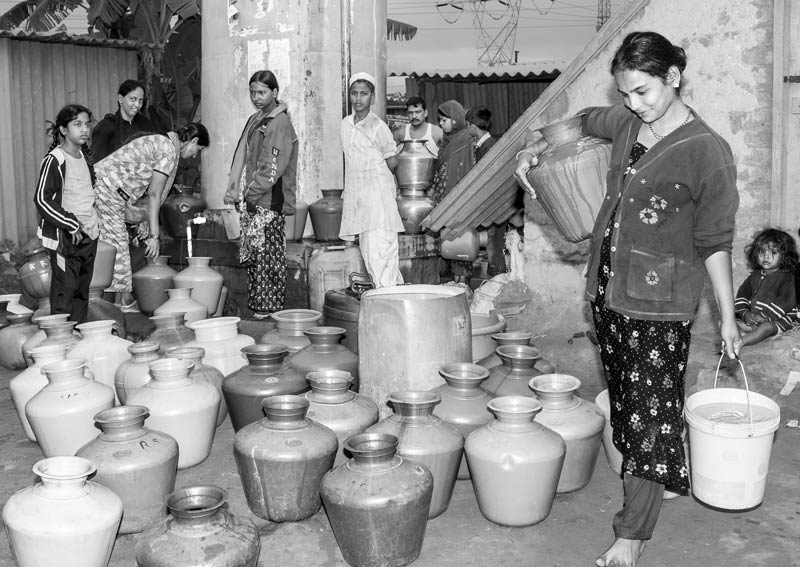

Too many seekers for the limited water supplied in a slum in Bengaluru, Karnataka

Finally, for the little water that is made available through piped water networks and other kinds of water sources, there are often many seekers. The limited volumes available in the pipelines (resulting from one or more of the above cited factors) leads to irregularity of supply as well as shortened supply durations at lowered pressure. This impedes the availability of adequate and continuous water supply. Underestimation of populations to be served and failure to factor in future population growth are also important factors leading to this impediment. The photo above depicts the situation from a slum in Bengaluru – a city where nearly 1.4 million people reside in over 1,500 unauthorized colonies and slums. Many of these settlements have been provided with public standpoints but the number of users per point is often high resulting in queue and rush, and injuries and conflicts. And worse of all, given the limitations of time and low water pressure, many seekers may be forced to return empty handed even after hours of waiting. The challenge of "too many seekers for little resources" is equally important in the case of urban slums as in many rural piped water schemes.

This photo story has elucidated the impediments to fulfilment of the water 'availability' norm that constitutes the basic requirement enabling enjoyment of the human right to water. It emerges from the description that these impediments are universally valid for the rural and urban settlements of India and much inter-connected and inter-dependent in nature. For example, on the one hand, in the absence of efficient O&M, availability of the water resources alone may not necessarily ensure availability of water supply. On the other hand, despite an efficient O&M in place, water supply may still be thwarted if there is scarcity of water as a resource. Similarly, neglect of local water sources can contribute to deepening of the water crisis emerging from reduced pipeline water supplies or the issue of too many seekers for the limited resources. It clearly emerges that availability of sufficient and continuous water supply is not a simple question of making governments responsible for installing water supply infrastructures to provide water to the hitherto 'uncovered' populations. An equally important need is to identify the possible impediments to sustainability of the infrastructures created and address them adequately from the start, so that the infrastructures can continue to fulfil the expected functions in a long-term perspective. This in turn calls for better planning, greater integrity and, accountability, and participatory approach. Water availability as a human right to water norm is an important precondition for not only reaching the SDG no. 6 – leaving no one behind in access to clean water and sanitation – but also an important input for a number of other SDGs such as no. 3 (good health and well-being), 4 (quality education), 5 (gender equality), 10 (reduced inequalities), and 11 (sustainable cities and communities). Thus, addressing the impediments to the 'water availability' norm for enjoyment of the human right to water is essential, all the more important in an era of climate change and other forms of global transformation such as urbanization.

<