Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2023

Innovation in Water Supply: A Case of “Best Out of Waste” in Jharkhand

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

22 March, 2023

According to the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, everyone should achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030. However, it is now known that the world is alarmingly off track on this target, and there is an urgent need to accelerate action in order to meet the Goal on time. Such a situation holds true for many parts of India, including the tribal state of Jharkhand, which receives quite a good rainfall, yet drinking water access is poor. The average annual rainfall in Jharkhand is around 1300 mm, which however results in a water availability of only 23.8 billion cubic meters (BCM) as surface water and 5.6 BCM as groundwater. As a result of the unique topographic and geological features of land here, comprising hard crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks of Precambrian age, up to 80% of the surface water and 74% of the groundwater is estimated to flow outside and become lost. This, in turn, is an important cause behind recurrent droughts in the state. Also, due to the geological formations, groundwater percolation is possible only through fissures and cracks and it gets stored in small voids. This precludes easy access and exploration of groundwater for human use. Despite this scenario, groundwater continues as the major source of drinking water in both rural and urban Jharkhand, and the dependence on handpumps is high in the villages. Since all districts are drought-prone, drinking water access in the summer months is often a challenge. Dumka is one such district where drinking water access is known to be a pertinent problem. This primarily rural district has suffered from drought more than once, the latest being in 2022. Community handpumps are the major drinking water source here, and piped water connections cover just about 37% households. The problem of drinking water access is most pronounced in Shikaripara Block where a cluster of six Gram Panchayats (village-level local government), have been especially identified as ‘dry zone’ where the water table is as low as 250 feet. These Gram Panchayats are Bankijor, Banspahari, Chitragaria, Hirapur, Saras Dangal, and Simanijor, where drying up of the community handpumps during summer causes great hardships for people. This photo story presents an innovative solution that has been implemented for addressing the drinking water challenge in one of the villages in Hirapur Gram Panchayat named Kulkuli Dangal. Shikaripara and its adjoining blocks are known for stone mining industry, and there exist several old abandoned stone mining pits which are seen as unutilized wasteland, but these actually help harvest water directly from rainfall and indirectly from the local runoff. The innovation described in the photo story deals with utilization of one such abandoned pit, converting it into a useful drinking water supply source, with water being drawn for a piped water supply scheme for 40 households in the village hamlet named Santal Tola. This creative innovation has been initiated by the local district administration under the able leadership of the Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla, with the district’s Drinking Water and Sanitation Department taking the lead role. It presents an excellent example of how local action using local resources can help accelerate change towards making universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water a reality by 2030. The title photo depicts the solar powered water lifting infrastructure at the mining pit in Kulkuli Dangal village in Dumka district, Jharkhand.

A view of Santal Tola hamlet in Kulkuli Dangal village

Kulkuli Dangal is a village located about 50 km south-east of Dumka town, the district headquarter. With a total population of 790 (census 2011), the village is mainly inhabited by Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes. Spread over an area of 232 hectares, the village has small hamlets, one of which is named Santal Tola. This remote hamlet is inhabited by 40 families belonging to the Santal tribe. The only source of water available in the hamlet was an open well, the water of which became contaminated especially during the rainy season, causing health issues. Though several attempts were made by the Drinking Water and Sanitation department (DWSD) to drill a handpump here, these failed because the hamlet is located in the ‘dry zone’. The only other option for drinking water for these villagers were the handpumps located in the neighboring hamlets, but these too were seasonal and used to dry up during the summer season, causing great hardships.

An abandoned stone mine pit filled with water in Kulkuli Dangal village

Faced with such a situation, the villagers brought up their water access problems before the Deputy Commissioner (the administrative head at district level) and demanded a safe and stable drinking water source. Since the village is remote, and not close to any surface water supply network, the only solution was to look for an alternate (unconventional) solution. The entire area in and around Kulkuli Dangal village is dotted with numerous abandoned stone mining pits which are nothing but wastelands. However, the large expanse of denuded rocky terrain enables collection of substantial rainfall from the monsoon showers which either flows away or drains into these deep pits. Generally, the catchment of these pits is very large, and their base is non-porous. Therefore, whatever water collects ends up being retained round the year. However, these water reserves remain largely unutilized because of the great depth of the pits. One such unused mining pit in Kulkuli Dangal is shown in the photo above.

The stone mine pit which supplies piped drinking water to Santal Tola

Considering the potential offered by the water reserves held in the abandoned mining pits, the Deputy Commissioner, together with the Executive Engineer of the DWSD, explored the possibility of making use of this untapped water resource to enable safe drinking water access to the villagers of Santal Tola. This water was tested and found to be free of chemical contamination. The microbial water quality could be easily improved with conventional water purification. This paved the way for implementing the innovative “Solar-based single village water supply scheme“. In the process of implementing it, the scheme was first passed by a village resolution, under the leadership of the village head. Next the DWSD prepared a project proposal which was sanctioned at the level of the Deputy Commissioner, who made use of a district-level fund called the 'Untied Fund' allocated by the state government. The community needed to make no financial contribution. Total cost of the project was about 1.5 million Indian rupees (approx. 18200 USD).

A view of the large catchment feeding the mining pit used for the water supply scheme

The mining pit which sources the water supply scheme is estimated to be around 100 feet deep, more than 150 feet long and 100 feet wide. It has a large catchment which helps collect a huge volume of water during the monsoon season, as can be seen in the photo above. Water quality in this and other surrounding pits is generally good because these are far from human habitation, and also no agricultural activities or industrial establishments exist around the area. So, the possibility of anthropogenic pollution of the water in the pits is minimal.

The water lifting infrastructure at the mining pit

The infrastructure which helps draw water from the mining pit comprises a 2.0 HP submersible pump run by solar power to lift the water and a pipeline to carry it to the village. The solar power is generated by multiple solar panels, and water is drawn from a depth of about 50 feet. The mining pit along with the water lifting infrastructure is shown in the photo above.

Location of the submersible pump in the mining pit and the pipeline carrying raw water

The pipeline carrying the raw water lifted from the mining pit

The solar panels which power the water lifting infrastructure

The water supply infrastructure inside Santal Tola

The raw water lifted from the mining pit is transported by a pipeline to Santal Tola, which is located at a distance of about 400 meters. Here it is first stored in a large 5000 liters capacity overhead tank, which is located at the highest point in Kulkuli Dangal village. This facilitates the efficient operation of a gravity-based water supply system in the Santal Tola hamlet. The other water supply infrastructure here comprises two water filters, a smaller ground-level water tank for storage of purified water, one public standpoint for supply of treated drinking water. The scheme is operated by a pump operator belonging to the local community, and the maintenance is also handled by the community itself.

The water purification system comprising two filters

One portion of the raw water from the overhead tank is distributed directly to the 40 households in Santal Tola through a pipeline network. Another portion is purified through two drinking water filters, as shown in the photo above. The first filter contains pebbles and quartz sand as a filtration medium, which helps treat turbidity by removing suspended solids, organic matter, colloidal particles, and also microorganisms. The second filter contains activated carbon that mainly helps remove certain particulate organic chemicals, and also color or odor from the water.

The tank for storage of treated drinking water

The water emerging from the purification process is stored in a 500 liters tank which is kept at a height of about 2.5 feet. Purified water from this tank is collected by the villagers from a community standpoint located nearby. Since the water lifting system is solar powered, it is functional throughout the day, continuously lifting water from the pit and supplying to the village without any interruption.

Public standpoint near the water storage tanks supplying treated drinking water

The public standpoint shown in the above photo supplies water from the smaller storage tank that holds treated drinking water from the filters. Safe drinking water can be collected from any of the two taps here any time during the day.

Collecting treated drinking water from the public standpoint in Santal Tola

Carrying home treated drinking water from the public standpoint in Santal Tola

Collecting water for domestic use from a household tap in Santal Tola

Every household has a tap connection which supplies water from the overhead tank in the hamlet through a gravity-based system. The tap water connection at home has greatly relieved the burden of women and girl children who now enjoy access to as much water as needed for fulfilling their domestic chores. In order to improve the ease of access to safe drinking water, domestic water filters have been additionally provided to every household within the Santal Tola. This is a temporary measure, and a new tank is being constructed near the existing water treatment plant to ensure that centrally treated drinking water is also made available to each household through the pipeline. This work is expected to be completed soon.

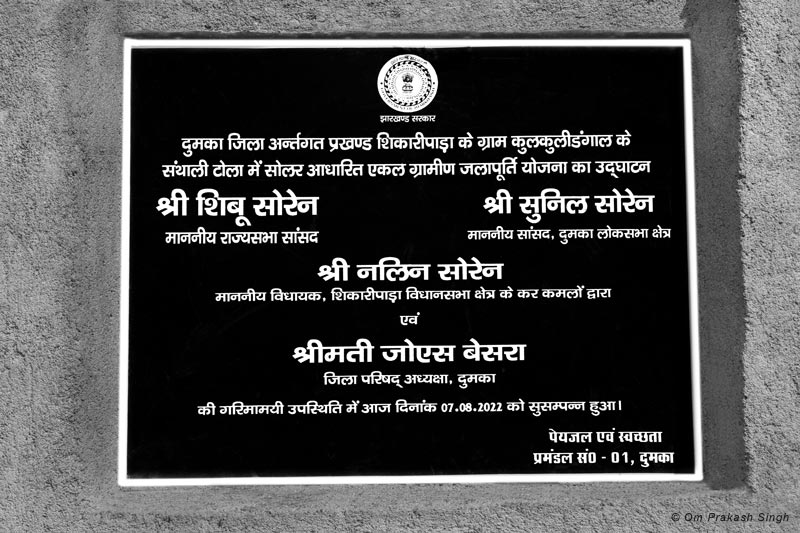

Inaugural stone marking the start of the innovative scheme

The Solar-based single village drinking water supply scheme was inaugurated on 7th August 2022, and it is operated and maintained by the local community.

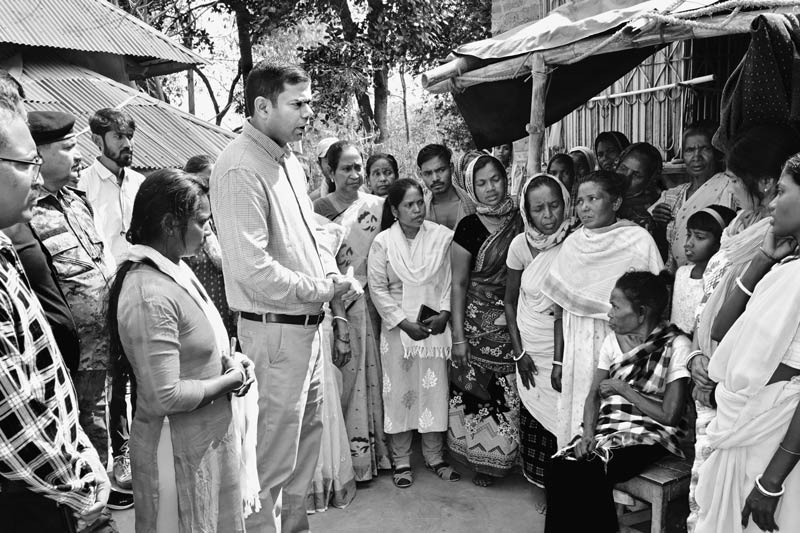

Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla with his team, interacting with the local community in Santal Tola

The local administration has been continuously visiting the remotely placed Santal Tola in order to closely monitor the performance of the water supply scheme, ensure its efficient operation, and upgrade the facilities as needed. The above photo depicts a recent visit by the Deputy Commissioner and his team who are interacting with the village community, attempting to identify any upcoming problems, and proposing solutions.

Happy children enjoying their leisure time in Santal Tola

Girl children are commonly burdened with the task of fetching domestic water from public sources. Before installation of the new water supply scheme in the hamlet, many girl children suffered the hardship of fetching domestic water from the distant handpumps located in other hamlets of village Kulkuli Dangal. However, with the coming of the piped water supply in the hamlet, they have been freed of this burden, and are instead able to enjoy their leisure time, as seen in the photo above.

The solar powered drinking water supply innovation presented in this photo story has undoubtedly made the "best out of waste", while accelerating the progress towards SDG 6 in the small tribal hamlet Santal Tola. The ‘waste’ referred here are the abandoned mining pits which are waste in two senses: first, as part of wastelands resulting from mining activities, comprising denuded, undulating landscapes which present little possibility, if any, of environmental restoration; and second, as landscapes that hold water yet not considered as water bodies because the water that they hold is not officially reckoned as a water resource in the region. The innovation holds many jewels in its crown, which offer important lessons for not only accelerating drinking water access for all, but also for ensuring people’s human right to water and enhancing water sustainability.

First of all, it has shown the way for enhancing water availability in an otherwise water scarce region by transforming an abandoned unusable mine pit into a valuable water reserve that has the potential of sustaining the water needs of a local community round the year. This implies a great potential given the fact that Jharkhand is a mineral rich state where mining is a very important economic activity. Consequently, the landscape in not only the district of Dumka, but the entire state, is widely dotted with abandoned mining pits. In Dumka district alone, where stone quarrying is an important activity, the number is estimated to be around 100 to 150. Additional 10-20 pits have resulted from villagers trying to illegally extract coal. At the level of the entire state, the number of such abandoned mining pits could be more than 3000, being a result of open cast mining of coal, bauxite and stone, among others. Dhanbad, Godda, Hazaribag and Ramgarh host most of such abandoned coal mine pits while Koderma, Pakur, and Sahebganj host the majority of stone mining pits. As proved by the innovation described here, by utilizing the untapped harvested rainwater stored in these pits, the volume of water availability can be enhanced manifold, thereby addressing drought-related water scarcity. The only precaution required would be to ensure that the water in the pits is free from serious chemical hazards.

The second benefit exhibited by the innovation is its decentralized nature, where the core water source, the water lifting and treatment processes and the human resources to run it are all situated at the local scale. By virtue of the decentralized nature, the project could be completed within a short period of time, hence cutting down on unnecessary implementation delays. Further, the operational effectiveness is increased through continuous administrative monitoring and support, and community engagement at every stage. This stands in stark contrast to centralized multi-village water supply schemes which depend upon distantly placed mains and kilometers of unattended piped distribution networks, where a fault at any one point may jeopardize water supply along the entire pipe, that may be difficult to be located and repaired quickly. Added to this is the use of solar power which again is a localized power supply arrangement, which makes the system independent of limitations arising from external power failures. This, in turn, enhances the sustainability of operation, and assures continuous water supply. It is to be noted here that for addressing the problem of ‘dry zone’, a multi-village surface water supply scheme from river Ganga is being planned which will cover parts of Shikaripara and neighboring Kathikund blocks in Dumka district. Similar networks are also being constructed for dry zones in Saraiyahat and Rampur blocks in the district. However, the multi-village water supply schemes are long drawn projects and scheduled for completion only in December 2024. This means that counting from the time when the innovative scheme was launched in Santal Tola in August 2022, an additional waiting period of 2.5 years was needed. Added to that would be the weaknesses of large multi-village pipeline water supply systems as described earlier.

Third, is the fact that the solar-based single village drinking water scheme in Santal Tola has succeeded in accelerating change for achieving SDG 6 by assuring the human right to water for all resident women, men and children within a short period of time. It has thus enabled everyone, without discrimination, to enjoy access to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The supply is ‘sufficient’ in terms of the quantity provided – it covers all their basic water needs, namely, drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, and personal and household hygiene. The water is ‘safe’ because the quality is good, free of microbial as well as chemical contamination. The water stored in the mining pit has been ‘acceptable’ to the local community as it has approved the mining pit as their water source through the village resolution, and everyone makes use of the water being supplied. ‘Physical accessibility’ is established through household taps that supply adequate water quantities whenever needed. And finally, the water is ‘affordable’, because these poor tribals did not need to share the cost of the expensive infrastructure.

The exclusive benefits of the water supply innovation at Santal Tola as described above offers important food for thought for policy makers. Considering that Jharkhand has limited water resources and is increasingly facing water scarcity, while there exist a large number of abandoned mining pits which offer a huge reserve of harvested rainwater, scaling up and replicating such an innovation could go a long way in sustainably addressing the water-related challenges not only in the district but in the entire state. It could also be replicated in other states that share similar contexts. The best way for scaling up and replicating would be to incorporate this approach at a policy level within Jharkhand and in other relevant states.