Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Leaving No One Behind: Ensuring Realization of the Human Right to Water in India

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

16 April, 2019

'Leaving no one behind' is the central promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development - a resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2015, aiming to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path. At its core lies the vision that no one will be left behind and that the human rights of all will be realized. With respect to water, the most important goal in the framework is Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) which aims to ensure availability and sustainable management of water for all by 2030. The first and foremost target under this SDG is to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water, through which it actually reaffirms the commitments regarding realization of the human right to water. The human right to water, recognized by the UN General Assembly and affirmed as legally binding upon States through a resolution of the UN Human Rights Council in 2010, entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. These uses include water for drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, and personal and household hygiene. Thus, it is an obligation of the governments to develop appropriate tools and mechanisms to achieve progressively full realization of obligations related to the right. The importance of realizing water as a human right for all has been reiterated through the World Water Day 2019 theme of "leaving no one behind". India is one of the 122 countries to have formally acknowledged the human right to water resolution in the UN. India has also played an important role in shaping the global SDGs. Therefore, the country's national development goals tend to reflect the SDGs in general and SDG 6 in particular. However, at present, the situation with respect to realization of the human right to water and achievement of target 1 under SDG 6 reveals that there is yet a long way to go. According to a report of the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India (2018), people living in 33% rural habitations still lack even the basic access to 40 litres per capita per day (lpcd) while as many as 83% rural households do not have access to piped water supply. Moreover, with respect to access to safe water, according to this report, people living in 18,258 rural habitations are exposed to the risk of arsenic in groundwater, while those in 13,492 rural habitations are exposed to the risk of fluoride in groundwater, besides many others affected by iron and salinity. According to another recent report on urban water supply in India, more than 30% households are left behind in access to tap water, and of those who do have tap water access, 38% are not facilitated with treated drinking water. Also, over 50% urban households do not have access to piped water supply within their premises. Further, people's access to safe water remains limited in schools, workplaces, farms and factories. The CAG Report notes that children in over 14% rural schools lack drinking water facilities. Against this background, this photo story aims to outline the norms and criteria within the human right to water framework that India must follow in order to ensure that no one is left behind in realizing the human right to water. It also outlines the norms and goals already set up within the rural and urban water supply frameworks in India that the country must strive to achieve in order to ensure that no one is left behind in accessing adequate and safe drinking water. The title photo depicts clean water being taken for drinking in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi.

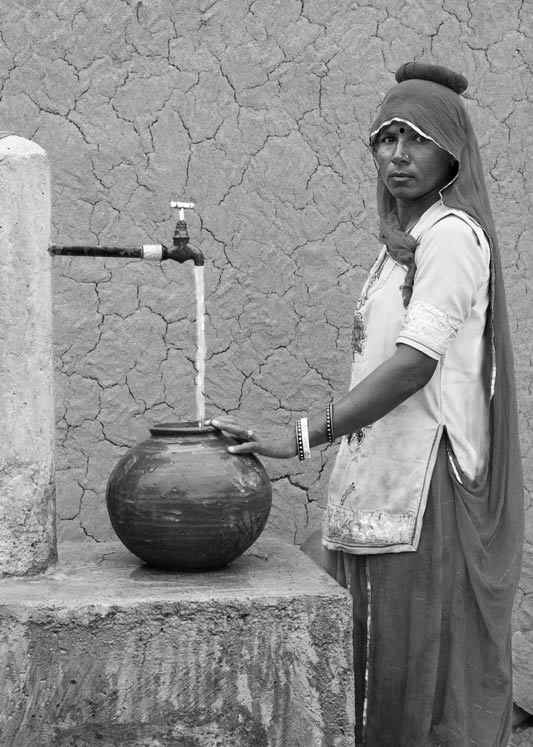

Sufficient water for drinking and personal uses available from a public tapstand in a village in Jaipur district, Rajasthan

According to the normative content of the human right to water as outlined in the General Comment (GC) No. 15 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (2002), 'availability' of water is the first and foremost criterion. Thus, the water supply for each person should be 'sufficient' and 'continuous' for personal and domestic uses, which ordinarily include drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, personal and household hygiene. 'Continuous' implies regularity of the supply so that it becomes sufficient for these uses. The quantity of water available for each person should correspond to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, following which standards and targets have been set under the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS) for rural India. This plan recognizes 40 litres per capita per day (lpcd) as a 'basic' requirement, and further envisages providing, by 2022, every rural person access to 70 lpcd of safe drinking water. An intermediary norm of access to 55 lpcd was set to be achieved by 2017. For urban areas, a supply between 70-150 lpcd has been recommended for different kinds of cities by the Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO).

The Maujampur drinking water treatment plant that supplies treated Ganges water to 39 arsenic-affected villages in Bhojpur district, Bihar

For ensuring the human right to water, the quality of water is the second most important criterion. The water for each personal or domestic use must be safe, which implies absence of micro-organisms, chemical substances and radiological hazards that constitute a threat to a person's health. Furthermore, water should be of an acceptable color, odor and taste for each personal or domestic use. It is the obligation of the government to follow the WHO guidelines for drinking water quality to develop national standards. According to government norms in India, all water supplied in rural and urban sectors should meet the minimum water quality standards. Following the WHO guidelines, as per IS-10500 standard of the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), all water intended for drinking should be free from coliform organisms. Regarding chemical contaminants, notably fluoride, arsenic, iron, nitrate and salinity, specific standards have been defined by BIS. For example, regarding arsenic which has carcinogenic effect on human health, the 'acceptable' limit set by BIS is 0.01 mg/L, while its 'permissible' limit in the absence of alternate source is 0.05 mg/L. It is the responsibility of the government to ensure effective implementation of the standards defined, through installation of community water purification plants (CWPPs) or other means. The Maujampur drinking water treatment plant, shown in the photo above, is a government intervention to provide safe drinking water in arsenic-affected villages by treating water from river Ganges, which makes it highly acceptable among the served populations.

A reverse-osmosis (RO) plant for supplying safe drinking water at workplace in the Regional Agricultural Research Station (RARS), Kumarakom in Kottayam district, Kerala

Apart from providing supply of drinking water which is safe from micro-organisms, chemical substances and radiological hazards that may constitute a threat to a person's health at home, the government is also responsible for ensuring such supply in all places where people spend significant amounts of time. This includes health and educational institutions such as schools and clinics, workplaces, farms and factories, detention centres like prisons, markets and other public places. In fulfilment of this responsibility, at RARS, Kumarakom, which is a part of the Kerala Agricultural University – a governmental institution, a RO plant has been installed for safe drinking water access in the office complex, as shown in the photo above. The RO plant purifies water drawn from a series of three tanks that collect rainwater from the premises of RARS.

A community handpump facilitates residents with water access in Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra

Physical accessibility to water and water facilities for everyone without discrimination, is the third important criterion to be fulfilled. Sufficient, safe and acceptable water must be accessible within, or in the immediate vicinity, of each household. According to WHO guidelines, location of the water source between 100 and 1,000 m or 5-30 minutes total collection time comprises 'basic' access, while water delivered through one tap on plot or within 100 m or 5 minutes total collection time comprises 'intermediate' access. 'Optimal' access is ensured with supply through multiple taps within the premises. In the past, physical access to water in India was reckoned through one hand pump or stand post for every 250 persons, with existence of the water source within the habitation or a distance of 1.6 km in the plains and 100 m elevation in hilly areas. These norms have been upgraded in 2013, with emphasis on piped water supply and placement of the source within domestic premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not more than 100 m from the household. However, the handpumps already in place continue to fulfil water needs in the vicinity, as shown in the photo above.

Adequate physical access through a groundwater-based village water supply scheme in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka

According to the revised guidelines in the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply, piped water schemes are to gradually replace handpump-based schemes. Further, the emphasis is on household-based connections, and by 2022, at least 80% of rural households would have piped water supply with a household connection. Simultaneously, the dependence on public taps is to be reduced to less than 20% by 2017, and to less than 10% by 2022. At present, public taps continue to be an important source of drinking water in rural India, providing safe and adequate water close to home, as is evident from the groundwater-based scheme shown in the photo above.

Water supply in an informal settlement through 'group connection' in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The GC No. 15 lays down the obligation upon governments to ensure that deprived urban areas, including informal human settlements, have access to properly maintained water facilities. No household should be denied the right to water on the grounds of their housing or land status. Thus, in urban areas, provision of adequate and safe water through piped water schemes with individual household connections or public tapstand in close vicinity is obligatory for civic bodies. Different municipalities fulfil this requirement in different ways. In Mumbai, where a substantial number of households are clubbed into tightly-packed slum clusters, a scheme of metered group water connection exists. Within this scheme, 5-15 households can form a 'tap committee' and apply for a group water connection, receiving regular supply of water at a subsidized tariff. One such group connection scheme is shown in the photo above.

Paying a nominal price for treated safe water in a village in Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal

The fourth criterion for assuring realization of the human right to water is economic accessibility, often also referred to as affordability. Water, and water facilities and services, must be affordable for all. The direct and indirect costs and charges associated with securing water must be within people's means and must not limit their capacity to buy other basic goods and services, including food, housing, health and education, guaranteed by other human rights. Though human rights laws do not require water services to be provided free of charge, governments have an obligation to provide free services or put adequate subsidy mechanisms in place to ensure that services always remain affordable for the poor. Even private parties and civil society can contribute in this effort, as is being offered by Sulabh International Social Service Organisation (SISSO) in the photo above. In Paschim Medinipur district in West Bengal, SISSO has helped set up a decentralized drinking water treatment plant operated through community participation that treats well water to make it free of pathogens and other contaminants, packages it and supplies at a nominal price of less than one rupee per litre, making it affordable for all.

Carrying treated safe drinking water for home use after making a nominal payment in Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal

Women expressing their concerns in a village water supply committee meeting in district Bhind, Madhya Pradesh

The fifth criterion for ensuring universal realization of the human right to water is non-discrimination. According to this criterion, water and water facilities and services must be accessible to all, including the most vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population, without discrimination on any of the prohibited grounds such as race, color, sex, age, language, religion, political or other opinion, nationality, property, birth, sexual orientation and civil, political, social or other status. Governments should give special attention to those individuals and groups who have traditionally faced difficulties in exercising this right, including women, children, minority groups, indigenous peoples, refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons, migrant workers, prisoners and detainees. Governments are obliged to take steps to ensure that women are not excluded from decision-making processes concerning water resources and entitlements, which in turn can help alleviation of the disproportionate burden women bear in the collection of water. The Strategic Plan (2011-2022) of MDWS lays down that women should be included in all aspects of decision making with respect to drinking water security planning, implementation, operation, maintenance and management. In this light, the above photo shows a meeting of a village water supply committee, also attended by one of the authors Dr. Nandita Singh, where local women actively raised their concerns in an attempt to solve problems regarding handpump maintenance in the village.

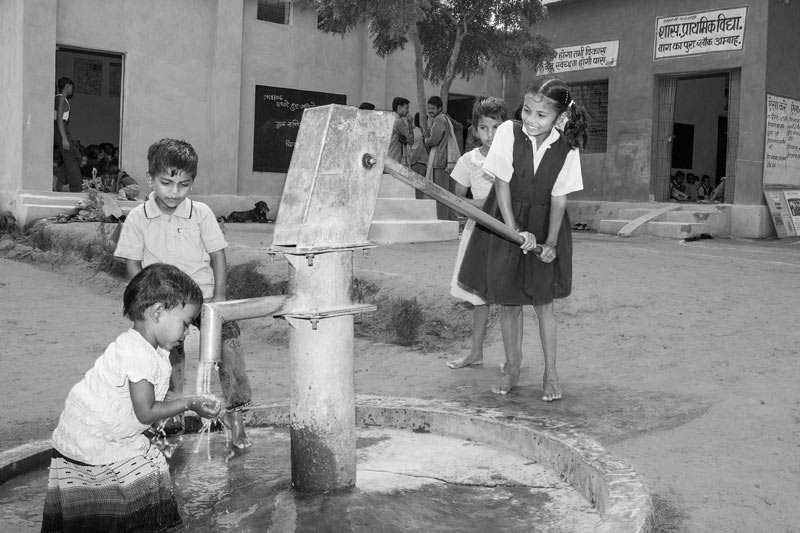

Children enjoying sufficient and continuous access to safe water in a school in Morena district, Madhya Pradesh

As stated above, in order to ensure universal realization of the human right to water, governments should give special attention to those individuals and groups who have traditionally faced difficulties in exercising this right, children being an important group. Governments should ensure that children are not prevented from enjoying their human rights due to the lack of adequate water in educational institutions and households or through the burden of collecting water. Thus, there is an urgent need to ensure provision of adequate safe water facilities within the premises of educational institutions, as is shown in the photo above. Towards this end, the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) of MDWS lays down the goal of ensuring that all government schools and child-care ICDS centres in rural India should have access to and use adequate quantity of safe drinking water. For private schools, it stipulates that supply of water must be ensured by enforcement of the provisions of the Right to Education Act by the Education Department.

A student carrying a bottle of safe drinking water from a 'Water ATM' located within a school premises in an arsenic-affected village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Besides ensuring access to adequate water in educational institutions, governments are also obliged to ensure children's access to safe water so that they are protected from harmful effects of pathogens, chemical contaminants and radiological hazards on health. Towards this goal, government in India started the Jalmani Scheme in 2008 with the objective of providing children studying in water quality affected rural schools with safe and clean drinking water, aiming to install 100,000 standalone water purification systems in government schools. In the arsenic-affected areas in Bihar, government is installing 'Water ATMs' based on the RO technology through private sector participation that ensure supply of safe water for children in government schools.

Students procuring safe drinking water free of cost from a 'Water ATM' within school premises in an arsenic-affected village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

A community tapstand providing sufficient and continuous water supply in a settlement inhabited by the Yenadi tribal community in Nellore district, Andhra Pradesh

The GC No. 15 lays down that governments must ensure that minority groups and indigenous peoples should be facilitated with enjoyment of the right. Thus, they must ensure the access of such communities to adequate and safe water supply and also help them design, deliver and control their access to water. There exist special provisions for financial allocations for ensuring water supply in habitations with substantial tribal populations or other weaker sections. The Yenadi are a primitive tribal group residing in Nellore and Chittoor districts of Andhra Pradesh, having an unstable economy. Some of them are also semi-nomadic. This primitive group has been facilitated with adequate and safe water access through piped water supply in their settlements, as shown in the photo above.

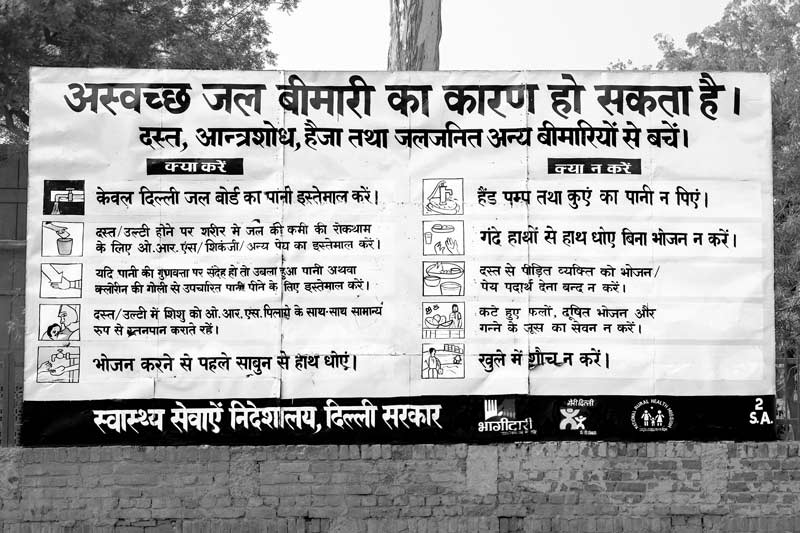

A billboard disseminating information about the connection between water and health in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

The sixth criterion for ensuring the human right to water is laid down as information accessibility. Accessibility includes the right to seek, receive and impart information concerning water issues. This criterion requires that individuals and groups should be provided with full and equal access to information concerning water, water services and the environment, held by public authorities or third parties. The Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply recognizes that awareness of all stakeholders on various aspects of ensuring drinking water security is very vital to achieving the overall sector objectives. It further acknowledges that this involves not just communication of messages but also adequate behavior change. Thus, the Strategy requires that States should design and implement appropriate behavior change communication and monitor the progress on the change achieved periodically. The billboard shown in the photo above describes the do's and don'ts with regard to consumption of water for prevention of diarrhea, dysentery, cholera and other water-borne diseases.

Piped water supply within domestic premises facilitating drinking water access in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

The UN's human right to water framework and target 1 under SDG 6 together define the expected global status with respect to universal and equitable access to safe and affordable water for personal and domestic uses by 2030 and beyond. Towards this end, a number of drinking water service-levels have been defined within the scope of the SDG framework. The highest attainable level in this ladder is that of 'safely managed' services which implies that an improved source is located on premises, available when needed, and free from microbiological and elevated levels of toxic chemicals at all times. Following these guidelines, through its Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply, the government in India has laid down the vision of piped water supply for all in adequate quantity with a metered tap connection within premises providing safe drinking water, throughout the year. This is a desired status in the urban areas too, with continuous uninterrupted water supply in all colonies and increase in numbers of urban settlements with 24x7 water supply. Through this vision, portrayed in the photo above, it is aspired that there would be healthy children and adults, and improved livelihoods and education, thereby ultimately promoting sustainable development.

This photo story has outlined the pathway planned for ensuring the realization of the human right to water by all in India, so that everyone, without discrimination, can enjoy access to adequate, safe and affordable water for personal and domestic use within rural as well as urban pockets of the country. In fulfilment of the norms and criteria described here, the government has already defined a way forward in the form of the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural drinking water supply, and a number of relevant policy and program guidelines for supporting urban water supplies. However, these goals appear very lofty. Further, as evident from the figures noted at the outset, achievement of the goals has so far been weak. Several millions are still left behind in accessing adequate, safe and affordable water. Moreover, an important dimension also to be considered is that of sustainability of the water supply services. Evaluations of previous water supply programs have identified "slipping back" of habitations as a significant cause behind the failure to reach defined goals in the sector. Slipping back can be caused by several factors, such as resource depletion, resource contamination, lack of operation and maintenance, and financial inadequacies. Further, failure to fulfil needs and aspirations of the users may also lead to rejection of water supply sources provided by the government. All these situations cause denial of the human right to water of the citizens. While the new Strategic Plan and the revised rural water supply guidelines as well as the frameworks guiding urban water supplies take into consideration most of the concerns stated here, a significant challenge still remains because of problems with effective implementation of the governmental frameworks. Lack of integrity and accountability, poor and unrealistic planning, competing demands from agriculture and industry and their negative impacts on water resources, as well as absence of effective public participation are some of the causes behind such a situation. Further, under impending climate change impacts, there is risk of intensification of the existing challenges through receding groundwater tables, drought, and floods. Given this context, it is obvious that if the lofty goals highlighted in the planning frameworks are to be realized, government must proceed with utmost caution. Only then will it be possible to ensure that no one is left behind in securing access to water for personal and domestic uses. Failure to ensure realization of the human right to water will lead to denial of several other human rights, such as health, education, decent livelihoods and overall human development. Since procuring and using water for drinking and other domestic uses is closely associated with women and girls, problem with enjoying the human right to water will deepen gender inequality. On the whole, denial of the human right to water and concomitant rights will, in turn, thwart attainment of sustainable development and prosperity, leading instead to inequity, distress and poverty. It is therefore of utmost urgency and importance that the government in India undertakes implementation of its water supply plans realistically and effectively so that no one is left behind in accessing water for personal and domestic use.