Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2023

Optimization of Traditional Drinking Water Sources: Accelerating Change in Jharkhand

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

22 April, 2023

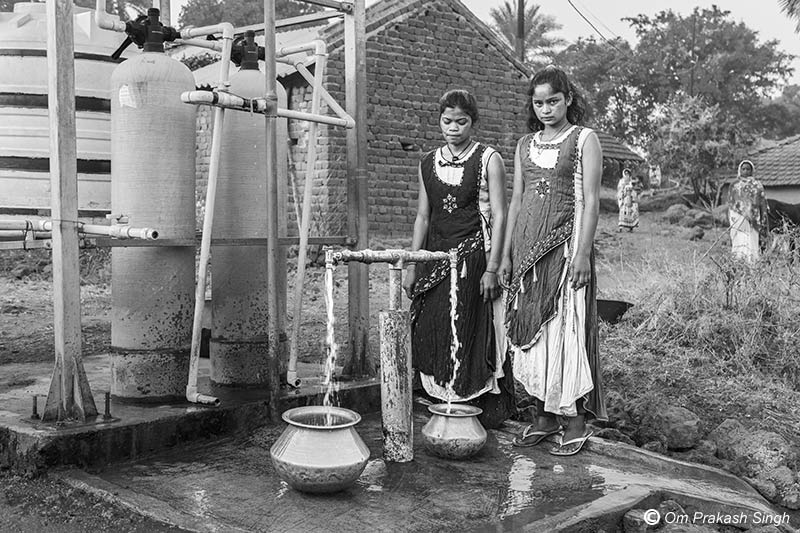

Access to water for personal and domestic use that is sufficient, safe, acceptable, and affordable water is a universal human right. It is also an important pillar in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework, and SDG 6 in particular aims for universal and affordable access to water for all by 2030. However, the world lags behind and there is need to ‘accelerate’ change at four times the current pace in order to reach the goal. In this light, this photo story proposes that the necessary ‘acceleration for change’ need not be based on an universal approach but should be instead rooted in an understanding of the nature of the local challenges that thwart progress. This, in turn, should be contextualized in the specific socio-ecological setting. This photo story focuses on the context of isolated tribal, hilly or forested areas in India where springs are a common natural water source traditionally in use through centuries. While springs have the potential of providing continuous water supply of good quality, these tend to be located at a distance from the habitation - at places out in the hills where a rock fracture or opening allows the groundwater to emerge on the surface. Therefore, the main challenge in this context is the ease of physical accessibility, which in turn may impact the quantity of water procured, because women and girls, who are the primary domestic water managers, need to carry heavy loads of water across narrow and risky hill paths. Also, there may be some concern with the quality aspect because springs are open sources out in the forests where the water can easily get contaminated from different sources. Accelerating change towards SDG 6 in such a setting would thus require a solution that can ‘optimize’ the benefits already obtained from the existing water sources, while minimizing the risks. This photo story presents an innovative approach for optimizing springs as drinking water sources in the hilly terrains of Dumka district, Jharkhand. More than 43% of the population in Dumka district is tribal (census 2011). It is also the home of six ‘particularly vulnerable tribal groups’ (PVTG) of which the Paharia is the largest. Physical inaccessibility of isolated tribal hamlets thwarts installation of conventional water supply systems which are commonly promoted as the solution for improving water access. The innovation in question involves optimization of local spring-based water sources in two tribal hamlets, inhabited by members of the Paharia tribe. The traditional spring-based water source here is called ‘Chua’, which is basically a pit dug in the ground around a spring in which the emerging water collects. Spring-based water sources of this kind have been traditionally in use for generations in this area. The ‘optimization’ primarily involves 3 aspects: first, protection of the spring source and its water (in terms of both quantity and quality) through construction of a sanitary well; second, installation of a solar-powered infrastructure for transporting the water up to the habitation; and third, supply of the transported water to the local community through a gravity-based piped water network. This innovative approach has been implemented by the district’s Drinking Water and Sanitation Department, under leadership of the Deputy Commissioner, Ravi Shankar Shukla. It presents an outstanding example of how local initiatives can play an important role in accelerating change towards sustainable development, by improving access to water. The title photo depicts water procurement at a public standpoint fed by a spring-based water supply system in Jiyatpani hamlet of village Dumarpahar, district Dumka, Jharkhand.

Members of Paharia tribal community in Jiyatpani hamlet, village Dumarpahar

The Paharia are regarded as the earliest inhabitants of Santal Parganas division where Dumka district is located. A large population of the Paharia tribe, mainly belonging to the sub-tribe called Malpaharia, resides in more than 600 villages of Dumka district. In general, the Paharia are recognized as a ‘particularly vulnerable tribal group’ (PVTG), on the basis of 4 criteria: pre-agricultural level of technology, low level of literacy, economic backwardness, and declining or stagnant population. They tend to reside in small, isolated hamlets located within hills and forest tracts, often unconnected by roads. They largely adhere to traditional livelihoods comprising primitive agriculture and forest produce collection, and in many cases, continue to depend upon their traditional drinking water sources. The two Paharia hamlets where drinking water access has been accelerated through the innovative approach includes Jiyatpani Tola of village Dumarpahar and Paharia Tola of Jhajhapara village in Dumka district.

A ‘Chua’ being used for collecting drinking water in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The name ‘Chua’ probably derives from the word ‘choona’ – which means seepage. It can be described as a water source generally fed by an underground seepage spring. The natural spot where water percolates from inside the rocks, may be modified in the form of a small shallow well, by digging a pit and then lining it with stones, as shown in the photo above. In many cases, the water discharge in such sources is slow, and hence the yield is small. However, some others, the discharge may be faster, leading to larger yields. Traditional spring sources are generally situated outside habitations in valleys or depressions, and people need to travel to them to fetch the water. These sources have good cultural acceptance because people believe that the water coming out from the ground on its own is much cleaner and of better quality.

The spring-based sanitary well which supplies piped water in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

Dumarpahar is a remote and isolated village situated amidst forested hills, at a distance of about 40 km north-east of Dumka town, the district headquarters. With a total population of only 241, distributed in 51 households (census 2011), it is a rather sparsely populated village spread over an area of roughly 492 hectares. Of these, 20 households belonging to the Paharia tribe, are located in a small hamlet named Jiyatpani Tola. There exists no water source inside the hamlet. For fulfilling domestic water needs, women and children as the major domestic water managers, had to travel about half a kilometer downhill everyday along a steep and undulating path to a seepage spring (chua). Access to this remote source thus caused great hardships, which became all the more difficult during the rainy season, when even the quality of the water risked being degraded. This traditional water source has been innovatively converted into a protected sanitary well, as shown in the photo above. Water quality inside the sanitary well has thus become protected amidst the leaves, foliage and other kinds of possible contaminants from the forest around.

A view of the above sanitary well, showing the solar panel in the background, in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

The Drinking Water and Sanitation department (DWSD) originally planned to address the problem of drinking water access in the hamlet by drilling borewells. However, this turned out to be a failure because the drilling machine could not reach the village in the absence of a proper access road to the village. Faced with such a precarious situation, the villagers brought up their problem before the Deputy Commissioner (the administrative head at district level) Ravi Shankar Shukla and requested an effective alternative. Given the unique circumstances, an innovative approach was adopted by the administration which was based on optimization of the already existing drinking water source. The traditional chua was thus converted into a closed and protected ‘spring-based sanitary well’, from which water is drawn into a piped water system using a submersible solar powered pump. The sanitary well shown in the photo above is 3 meter in diameter and 5 meter in depth. In the normal season, the well remains charged with about 10 feet of water, while in the rainy season, it may further rise to around 13 feet. However, during the summer season water level tends to decrease slightly to around 8 feet.

The solar panels which power the submersible pump in the spring-based sanitary well in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

The spring-based sanitary well is located at the base of a hill amidst a dense canopy of tall trees. Hence the well has poor exposure to sunlight. Consequently, the solar panel which powers the entire infrastructure has been fixed higher up on the hill, so that it can obtain maximum sunlight for a longer period of the day, and thereby produce maximum power. The solar power helps run a 3.0 HP submersible pump fixed inside the spring-based well, which draws water from the well, sending it through a pipeline up to the hamlet. The solar power is generated by multiple solar panels, shown in the photo above. These panels produce a total power of 2835 watt at peak.

The water supply infrastructure inside Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

The water lifted from the sanitary well is transported by a pipe up the hill to Jiyatpani Tola. Because of the height of the hill, the pumping of the water takes place in two steps. The water from the source is first pumped to a large intermediate feeder tank which has a capacity of 8000 liters. From there it is transferred to a smaller 5000 liters capacity overhead tank, which is located near the highest point in the hamlet. This facilitates the efficient operation of a gravity-based water supply system in the hamlet. The components of the water supply infrastructure are shown in the photo above. This includes the overhead tank, two water filters, a smaller water tank for storage of purified water, and one public standpoint with two taps for supply of treated drinking water.

The water purification system at Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

Though the quality of the water received from the sanitary well has been tested to be excellent, in order to ensure full safety of the supplied water, one portion of the water from the overhead tank is purified through two drinking water filters, as shown in the photo above. The water emerging from the purification process is stored in a 500 liters tank which is kept at a height of about 3 feet from the ground. Purified water from this tank is collected by the villagers from a nearby community standpoint having two taps. Since the water lifting system is solar powered, it is functional throughout the day. The tank starts filling when sufficient sunlight comes in the morning and stops when the sun starts setting in the evening. The scheme is operated by a pump operator belonging to the local community, and back washing of the filter as per requirement is also handled by the community itself.

A closer view of the water filters at Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

The water filters installed for purification of the spring water received from the sanitary well use a mixed media. This consists of a layer of anthracite coal above a layer of fine sand. The upper layer of coal traps most of the larger floc, and the finer sand grains in the lower layer trap smaller impurities, this process being called in-depth filtration. As the impurities are not simply screened out or removed at the surface of the filter bed, these have a third layer consisting of a fine grained dense mineral called garnet, at the bottom of the bed, which finally removes any remaining impurity.

-copy.jpg)

The tank for storage of treated water at Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

Collecting treated drinking water from the public standpoint near the filters in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

Public standpoints inside Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

In addition to the public standpoint near the overhead tank (seen earlier), water from the overhead tank is supplied at a number of places in the hamlet through a pipeline network based on gravity. There exist 5 public standpoints, of which two are seen in the photo above. Water is supplied through the standpoints for around 2 hours each day.

Collecting water for domestic use from a public standpoint in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

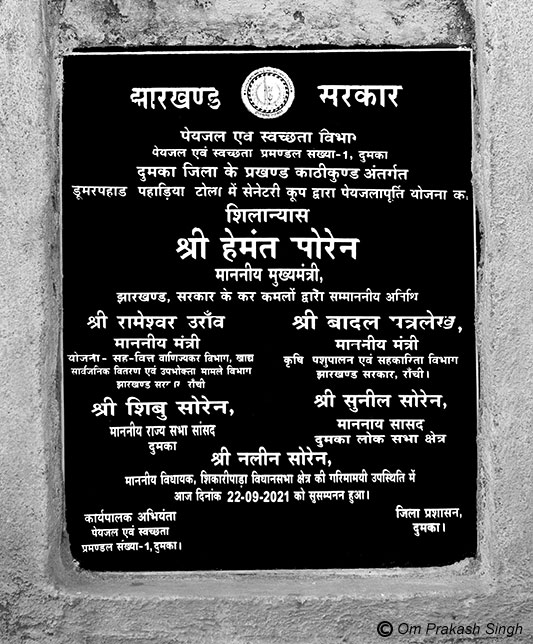

Inaugural stone marking the launch of the innovative water supply scheme in Jiyatpani Tola, village Dumarpahar

The solar-based single village drinking water supply scheme was inaugurated on 22nd September 2021. The scheme is funded by a district-level fund called 'Untied Fund' allocated by the state government. Total cost of the project was about 1.5 million Indian rupees (approx. 18200 USD). The community needed to make no financial contribution.

The traditional spring-based source – chua – which continues to be used in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The second village Jhajhapara is closer to Dumka town, the district headquarter, situated at a distance of about 30 km. It is in fact very close to Masanjore Dam on Mayurakshi river. Spread over an area of about 148 hectares, the total population is 311 (census 2011), distributed in 68 households. Of these, 45 women, men and children living in 12 households, are located in a small, isolated hamlet which is called Paharia Tola. This hamlet is mainly settled by members of the Paharia tribe who migrated here about 18 years ago from their earlier settlement near the then newly constructed highway connecting Dumka town with the dam. For fulfilling their water needs, they depended upon traditional spring sources. One of these is located closer to the settlement - a chua which is lined with stones. This chua is still well maintained and continues to be used as a domestic water source, as seen in the photo above. Two other springs are also commonly used by the people, but these are more distant along the hill slopes, located at a distance of 90 meters or more.

A view of the above chua, showing the new spring-based sanitary well in the background in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

Water yield in the chua near the settlement is small and tends to become insufficient, especially during the summer months, while the other springs present problems of physical accessibility. Therefore, the villagers requested the administration for an alternate water source that could improve the water access especially for the women and girls. However, drilling a borewell in the rocky terrain didn’t become possible due to lack of a road connection. Consequently, there was need to find a local solution. Under the leadership of the Deputy Commissioner, the spring-based water supply approach was once again adopted for this hamlet. This time the optimization comprised creation of a new spring source at a close distance of just about 2 meters from the traditional chua. This new spring source, protected by constructing a sanitary well around it, is visible in the above photo in the background.

The new spring-based sanitary well that supplies drinking water in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The new spring source has been protected as a closed ‘spring-based sanitary well’, from which water is drawn into the piped water system using a 1 HP submersible solar powered pump. The spring-based sanitary well shown in the photo above is 3 meter in diameter and 5.5 meter in depth. For a major part of the year, the well is said to yield around 2000 liters of water per day. However, in the summer season the water level tends to become low, as the recharge is slow.

The water supply infrastructure together with the solar panels in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

Water is lifted from the sanitary well up on top of the adjacent hill to be stored in an overhead tank having a capacity of 2000 liters. The location of this tank at this great height is meant to facilitate the efficient operation of the gravity-based water supply system. The overhead tank and other components of the water supply infrastructure are shown in the photo above. Since this is also the point which receives the maximum sunlight amidst the forested surroundings, the solar panels have been installed above the tank. There are three panels which together produce 900 watts of solar power that makes the submersible pump inside the spring-based well work. The tank starts getting filled when sunlight becomes strong enough in the morning and it stops in the evening when the sun starts setting.

A household tapstand supplying the water from the spring-based well inside Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

Water from the overhead tank is supplied every afternoon (around 3 o’clock) for about an hour. There are 12 household tapstands and one public standpoint inside the settlement. The water quality is very good and both in situ and lab tests show that the water quality parameters are well under permissible limits. The only problem is some level of turbidity, for which earlier a small-size filter was attached in the rising main. However, after the filter became choked, it was removed, and the current plan is to provide a domestic water filter to each household shortly.

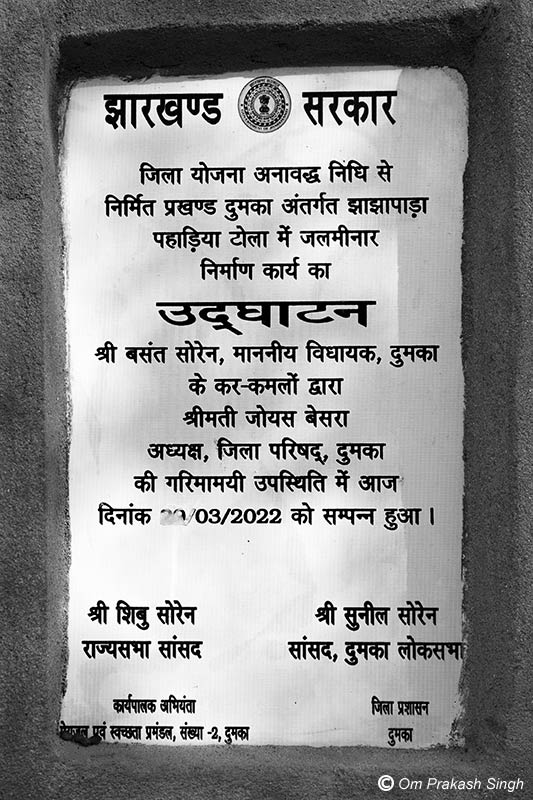

Inaugural stone marking the launch of the spring-based water supply scheme in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The solar-powered drinking water supply scheme in Paharia Tola was inaugurated in March 2022. As with the Jiyatpani Tola’s scheme, it is funded by a district-level 'Untied Fund', cost of the scheme being about 0.8 million Indian rupees (approx. 9800 USD). The community needed to make no financial contribution to the scheme.

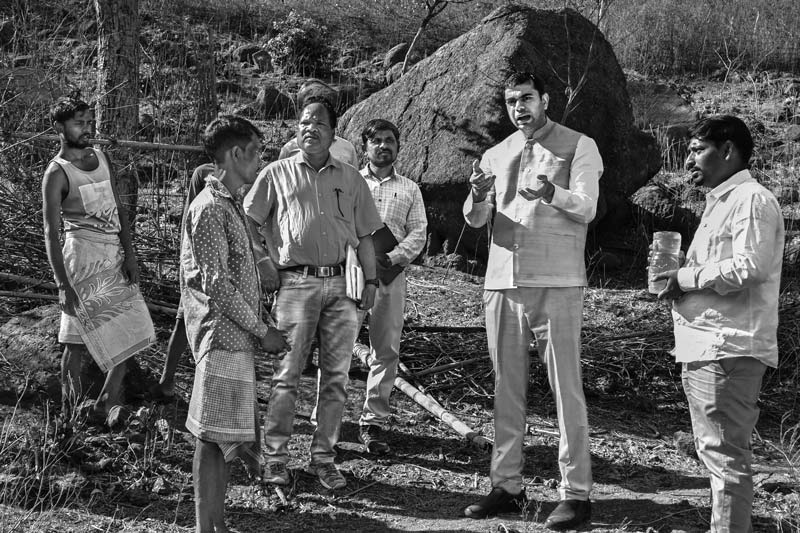

Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla inspecting the spring-based sanitary well in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The local administration has been continuously monitoring the performance of the water supply schemes in the two remotely placed tribal hamlets in the district. They try to identify any upcoming problems and apply solutions so as to ensure their efficient and effective operation. The above photo is from a recent visit by the Deputy Commissioner and his team to Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara where he is inspecting the water level inside the sanitary well during the dry season in the month of March.

Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla (second from right) and his team in discussion with community members in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

The water supply schemes are based on community participation where the local community has been involved in different ways. Not only is the pump operated by the local community, but they also contributed manpower during the construction phase. Further, water quality is regularly monitored by the local village Jalsahiya (water volunteer) using a ‘Field Test Kit’. Also, it is felt within administrative circles that the community’s continuous support and cooperation is essential to ensure long-term and effective operation of these water supply schemes. For these reasons, the Deputy Commissioner and his administrative team maintain a close connection with the community, always consulting them and discussing issues during their visits as seen in the photo above.

Nandita Singh, from Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden interacting with the community women during her field visit in Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara

When the authors Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh visited Jiyatpani Tola, Dumarpahar village and Paharia Tola, village Jhajhapara, the community members appreciated this unique approach adopted by the local administration. They believe that the approach has great potential to fulfil the water needs of the community and relieve the burden of women and girl children who are mostly responsible for procuring water for various domestic chores. The women especially said that though the water quality and quantity available from the traditional spring sources was always reliable, given the distance and difficult terrain, it was a challenge for them to access and fetch adequate water from these sources. With the coming of the piped water from the optimized spring-based sanitary wells, this challenge is addressed.

The two case studies presented in this photo story illustrate the value of traditional drinking water sources in the process of accelerating change towards improved water access for all by 2030. They also emphasize the centrality of the innovative spring-based approach for water supply adopted in this process. In both the cases, traditional drinking water spring sources have been innovatively optimized, with the objective of overcoming the challenges posed by them while maximizing their benefits. On the positive side, these natural water sources are available in the remote tribal localities and also quite reliable in producing continuous water yield which is generally good in quality. However, they present two major challenges. First is the issue of their accessibility due to the distance and location, resulting in hardships for the users, and second is the risk of water contamination because these are open sources lying in forested patches. Both these challenges were innovatively addressed by adopting an approach that was based on a simple, decentralized, low-cost technology that can be easily operated and maintained by the local tribal community. Combined with the benefit of local acceptability, this innovative approach has the potential of delivering the same results that are provided by larger, centralized, expensive, multi-village water supply schemes which however, are also known to present several weaknesses. The innovativeness of the approach comprises, first, the conversion of the open traditional springs into protected sanitary wells, second, introducing a solar-based water lifting system, and third, supply of the lifted water at the doorsteps of the community through a gravity-based piped network. The innovative use of solar power for running the water pumps and the gravity-based networks are added advantages which enhance sustainability of the operation in areas where regularity of electricity supply is a problem. Thus, it clearly emerges that while these two tribal hamlets had been already ‘left behind’ in the process of enjoying universal and affordable access to water, optimization of their traditional drinking water sources ‘accelerated’ their progress towards this crucial sustainable development goal by enhancing the ’ease of access’ to safe water.

There is no doubt that the above innovative spring-based approach for water supply has yielded unparalleled benefits, but it is equally important to ensure that these results are sustained in the long term. This, in turn, depends upon technical efficiency and effectiveness of the infrastructure as well as continued source sufficiency. The former is being adequately handled by the administration, but special care is needed for the second aspect. By their basic nature, springs are dependent upon underground water flows which in turn fluctuate through seasons. Spring discharge is maximum during and immediately after the monsoon rains, while it decreases with advance of the dry season. Such seasonal variability in water flows may get further deepened by climate change impacts and other anthropogenic factors such as land use changes. The results of the innovative spring-based approach for water supply can be efficiently and effectively reaped only when sustainability of the water flow in the source springs is ensured. Towards this end, springshed management needs to be practiced at the local scale, so that groundwater percolation can be maximized in a climate change regime.

Another important observation about these spring-based water supply systems is that the sanitary wells developed in this innovative approach are finite sources of water because the springs feeding them recharge slowly. In order to ensure that the communities are able to enjoy a steady water access round the year, a spring-based piped water supply scheme must always draw a balance between the water intake for supply and the total spring discharge on a daily basis. Further, if the community is served by more than one spring source, a strategy for enhancing the water stock for supply could be to divert all additional water flows into the main sanitary well. Simultaneously, the user community must be educated about the limits of daily water use and making judicious use of the piped water supply. They must also be sensitized about preventing any water wastage.

The innovative solar-powered spring-based approach for water supply is an important strategy to ‘accelerate change’ towards improved water access not only in the two villages, but widely across Dumka district and the state of Jharkhand, where use of springs as traditional drinking water sources is an age-old practice. It is an equally widespread practice outside in several other hilly states in the country. In many of these places the challenges observed for the two Dumka villages hold true. In this light, the recommendation that emerges from this photo story is that the solar-powered spring-based approach for water supply offers tremendous scope of scaling up in hill communities across the country. Efficiency and effectiveness of the approach should be further enhanced by adopting an integrated approach where multiple spring flows are diverted to a single sanitary well, and springshed management and community education for prudent water management are also combined in the approach.

Finally, for ensuring state-wide, and country-wide adoption of the innovative approach described in this photo story, there is need to integrate the approach at appropriate policy level. At present, the isolated cases presented here have been supported by local funding sources, which may not be able to support the operation and maintenance of the schemes on a long term basis. Sustained financial and administrative support for the action can go a long way in developing and promoting this unique, innovative, solar-powered spring-based water supply system as an important local decentralized alternative for accelerating change towards improved water access under SDG 6, both at state and national levels. In fact, the operational guidelines of the current Jal Jeevan Mission make a reference to the possibility of exploring and implementing ‘gravity and / or solar power-based water supply schemes in tribal / hilly / forested areas’. It also mentions springs as a reliable source for drinking water in hills and mountains. There is need to mainstream this focus, giving it a practical shape using the template of the innovative approach described above.