Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2018

Quenching the Thirst in the Driest Place of India: A Nature-Based Solution

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 July, 2018

In the western part of India is located the Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, which is characterized by aridity with scanty precipitation, sandy soil and dry air. At the heart of Thar Desert lies Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan where the erstwhile tehsil (sub-district) Ramgarh is located. This area, characterized by vast stretches of sand dunes, is the driest place of India where the climate is hyper-arid, with temperature up to 48°Celsius during summers and average annual rainfall not exceeding 100 mm. The rain is often erratic and received largely during the monsoon months of July to September. Further, droughts due to failure of rainfall are not infrequent and rivers and streams are conspicuous by their absence. The water table is very deep, more than 65 m, and the groundwater is not only saline but at some places also contains fluoride above the permissible limit of 1.5 mg/l. In these circumstances, sustainable access to safe drinking water could be a great challenge for the people who inhabit the region. However, for centuries the inhabitants of this place have been dependent upon a nature-based solution for quenching their thirst. They have valued rainwater as the most precious resource and attempted to catch every drop of it using simple, time-tested, and reliable techniques based on traditional knowledge and local resources. These rainwater harvesting techniques have provided them water security for drinking as well as livelihood and other uses, helping them thrive in a hostile climate with extreme variability. This photo story aims to demystify how women, men and children quench their thirst through rainwater harvesting in Ramgarh region. It sets out to describe the case of Netsi, a medium-sized village in the area, spread over an area of 168 sq. km., and located about 73 km north-west from the district headquarter Jaisalmer. As per Population Census of 2011, the village is inhabited by 967 individuals living in 168 households, with animal husbandry and agriculture as the main modes of livelihood. According to local residents, the village is well-known in the area for its huge pond called Viprasar which holds rainwater (‘palar pani’) during years having good monsoon rains, and always provides percolated shallow groundwater (‘rejwani pani’) through small shallow wells called ‘beris’, even during the drought years. The surface and shallow groundwater together provide sweet and safe drinking water to the villagers round the year, irrespective of the climatic pressures. The title photo shows beris visible in the receding waters of Viprasar during the spring season.

A view of the village pond called ‘Viprasar’ filled by monsoon run-off

Viprasar is a large pond located on the outskirts of village Netsi which is known to be fed by a catchment spread over 25-30 km. This pond gets filled-up with runoff resulting from 1-2 good monsoon showers totalling a quantum of about 30-50 mm rain. This can occur once every 2-3 years, and the surface water can remain available for a period up to one year. The pond was created about 300 years ago jointly by residents of 12 neighboring villages as a source of ‘sweet’ drinking water, since the groundwater in the area is saline. Presently, it is only Netsi that depends on it.

Women proceeding to fetch drinking water from Viprasar

Viprasar is located at a short walking distance from the village settlement, which reduces the burden on women and girls who are primarily responsible for domestic water management. During the time the pond retains water, they commonly fetch water during late hours of morning and early in the evening. There exists no discrimination based on caste or ethnicity regarding the right to procure water, nor are there any specific area allocations from this perspective.

Drinking water being filled into pots at Viprasar

Viprasar water is used exclusively and unanimously for drinking in Netsi since it is considered to be clean and ‘sweet’. Strict rules are followed by the villagers for upkeep of the water quality. Bathing and washing is strictly forbidden, and infringement can invite a fine of Rupees 5,000 (approx. 73 USD). Though there exists piped water supply in the village fed by the Indira Gandhi Canal, this water is not considered potable since it has been found to be dirty and polluted.

Village women preparing to leave after filling their pots with water at Viprasar

Women and girls returning home with pots full of cool and sweet drinking water from Viprasar

Women and girls socializing on the cool shores of Viprasar

Viprasar is not only a place for fetching drinking water, but for the women and girls its cool shore amid the warm sand also serves as an important social venue. They often come in small groups to collect water and spend some time on the shores, gossiping or discussing important issues or simply enjoying moments of leisure.

Viprasar water being collected in bulk

Though the most common mode of water collection from Viprasar is manual procurement by women and girls, sometimes drinking water is also obtained by men in bulk using camel carts or other modes of transport. Though meant exclusively for drinking, this water may be used at home or sold within the village or outside to families that lack manpower or face other limitations in procuring the water directly. During the winter months when it is quite cold in the desert, men may assist women by fetching water in bulk in a similar manner.

'Beris' emerging out of the receding waters of Viprasar

As the dry season advances, surface water in Viprasar starts slowly disappearing, some of it being used up, while the rest simply evaporates or percolates into the ground. Thus, Viprasar is also a percolation tank supporting groundwater recharge, enabling water security in the village. The percolated shallow groundwater is sweet and safe and becomes available for drinking through beris that are dug in the base of Viprasar. The beris are approx. 8-10 m deep and have diameter of about one meter.

Viprasar turned into a ‘taanda’ with ‘beris’ after drying up of the surface water

With further progress of the dry season, the surface water completely disappears and Viprasar is turned into a ‘taanda’ (a cluster of beris) that supports drinking water supply for the rest of the year. It is said that the taanda at Viprasar originally had 120 beris belonging to 12 villages, of which one was Netsi. Presently, only 24 beris are in use, primarily by Netsi women. The other villages now have their own drinking water sources. The beris in use have been rejuvenated in the recent years through collaborative efforts of the organization Sambhaav and the community, under the leadership of Chattar Singh.

Procuring drinking water from a 'beri' in Viprasar

During the dry months, women and girls procure fresh drinking water from the beris. They often make two trips a day, once every morning and evening. They claim that water in the beris doesn’t dry up even up to seven ‘akaal’ (droughts). In local parlance, drought refers to a year when monsoon rainfall is so little that there is not enough runoff to get collected as surface water in ponds. In a ten years cycle, 2-3 consecutive years may often turn out to be drought years. During drought years, water from Viprasar beris is fetched by residents from many neighboring villages when their own drinking water sources dry up. In recent decades, Viprasar taanda has been seen to support drinking water supply up to three consecutive droughts, after which sufficient rainfall was received to fill the pond again.

Returning home with pots full of drinking water from a 'beri' in Viprasar

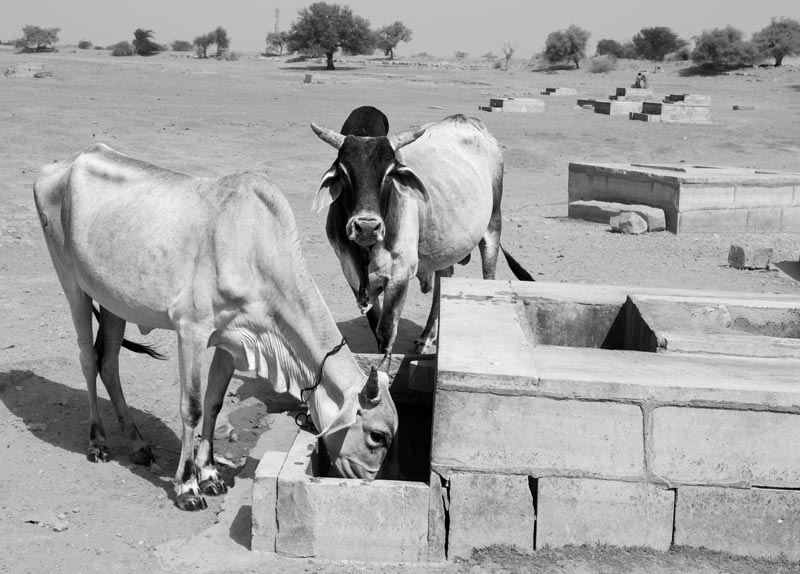

Drinking water from a 'beri' being withdrawn for animals

The Viprasar taanda is not only a source of drinking water for human populations, but also serves the animal wealth of Netsi and the neighboring villages. Every beri has a ‘kheli’ on one side which is a small shallow tank into which water from the beri is filled for the animals. Netsi village has a huge animal population of more than 16,000 including sheep, goat, cattle and camel, the drinking water needs of which during the dry season is fulfilled by the Viprasar beris. During and for some months after the rainy season, surface water collected in smaller ponds and pools is used for animals.

Water from 'beri' being transferred into the ‘kheli’ from where animals can drink

Goats drinking water at a 'kheli' in Viprasar

Cattle drinking water at a 'kheli' in Viprasar

A ‘tanka’ for harvesting rainwater in Netsi

Another nature-based traditional solution for drinking water in Netsi is the ‘tanka’. A tanka is an underground tank constructed for harvesting rainwater from a large a saucer-shaped catchment that has a gentle slope towards the centre. A tanka could be located in open communal space or in the backyard of a house or even in the agricultural field. Meticulous care is taken before the onset of monsoons every year to clean up the catchment so as to uphold the quality of the water to be harvested. The harvested rainwater may be used for drinking by humans as well as the animal stock.

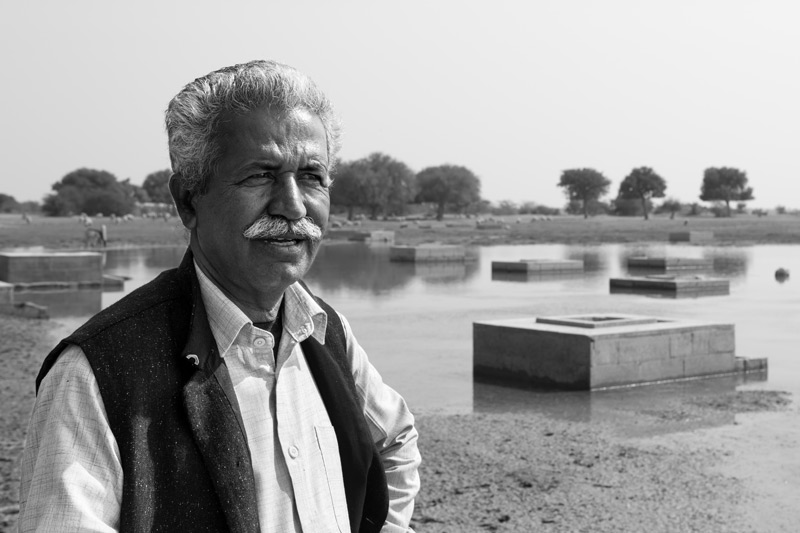

Chattar Singh - the Water Leader - who has mentored and supported rejuvenation of traditional rainwater harvesting structures in Netsi

The village community of Netsi has been able to revive and rejuvenate its traditional rainwater harvesting structures under able leadership and guidance of Chattar Singh, who is a member of the non-governmental organsation Sambhaav. He is a resident of village Ramgarh and is highly knowledgeable in local water resources as well as natural resources in general. He has worked relentlessly together with the local communities to improve their access to water for drinking and other uses through nature-based solutions, having facilitated not only Netsi but 22 other villages in the area.

Through the example of village Netsi, this photo story has illustrated how in Ramgarh – the driest place of India – drinking water security has been achieved through years, generations and centuries by adopting simple nature-based solutions rooted in rainwater harvesting. A place where the average annual rainfall is as low as 100 mm, and climate variability is high, by carefully harvesting and preserving each and every drop of the scarce rain that falls, women, men and children are able to enjoy access to sweet and safe drinking water for themselves and their animal wealth. In fact, this is a treasure known to last even up to seven years in the event of drought, thereby also helping adapt to climate extremes and variability. Further, since rainwater is the purest form of water, this solution also offers the possibility of mitigating the problem of groundwater quality, which in this region is affected by salinity and fluoride. The solution further offers comparison with the alternative of long-distance surface water supply in bulk which lacks reliability and hence faces rejection for drinking. Practicing this nature-based solution requires community-based management and for the women and girls it implies the need of walking up to the village outskirts to fetch the water. However, the benefits offered far outweigh any hardship, with men lending a helping hand when needed. The nature-based solution for drinking water presented above is an eye-opener for many other parts of India where rainfall is plenty but there exists dearth of safe drinking water. Glaring examples include the erstwhile ‘wettest place of the world’ – Cherrapunji in Meghalaya – and the larger North-Eastern Hill Region as well as the Himalayan region in general. In these places, in the wake of climate change, presently many rural and urban communities face the risk of drought especially during the dry season because the means to harness and conserve the high rainfall received do not exist. On the contrary, even the means of conserving water in nature through the green cover has come to be systematically destroyed as illustrated in the previous story dated 21 April 2018. At many places, degradation of water quality is a formidable challenge, with arsenic, fluoride, nitrate, salinity, iron and many other contaminants in drinking water. From this story, the important food for thought to emerge is that if local communities, and especially their women as domestic water managers, are to be facilitated with sustainable access to safe drinking water in the rural and urban communities that face quantity or quality challenges, then rainwater harvesting is a feasible and powerful nature-based solution. It may take different forms in different areas depending upon factors such as topography, stratigraphy, soil, rainfall, and the local knowledge, expertise and resources available, but what is important is adoption of the principle itself. If 2-3 showers of monsoon rain can enable drinking water security in the heart of desert land, there is no doubt about its potential in areas receiving higher rainfall. Rainwater harvesting in various forms can enable realization of the human right to water and several other concomitant rights such as health, education and decent livelihoods. It offers the possibility of equipping communities to address the challenge of climate change, degraded water quality and enable water-starved communities progress along the path of sustainable development. Adoption of this solution can undoubtedly help reach Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as ‘clean water and sanitation’ (6), ‘good health and well-being’ (3), ‘sustainable cities and communities’ (11), ‘climate action’ (13), and ‘gender equality’ (5). Thus, it is time to adopt this principle in policy and practice as widely as possible.