Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Rural Drinking Water Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

16 June, 2017

India has a large rural population of over 900 million living in more than 176 million households distributed across 1.7 million rural habitations. According to the Census of 2011, the proportion of these households enjoying access to drinking water source within premises is only 35%. The rest have to procure drinking water from outside sources, with over 22% using sources over 500 meters away. This figure illustrates the extent of challenge in accessing drinking water in rural India. The challenge is further deepened by factors such as increase in population, defunct drinking water supply systems, poorly maintained hand pumps and tubewells, and lowering of the ground water table, etc. Additionally, the access to a drinking water source itself does not guarantee access to ‘safe’ water. Water is defined as ‘safe’ if it is free from biological contamination (bacteria, viruses, protozoans, parasites etc.) and chemical contamination (excess fluoride, salinity, iron, arsenic, nitrate, etc.). Up to the census of 2001, access to ‘safe’ drinking water implied access to water from tap or handpump or tubewell within or outside the premises, which are also considered as 'improved' drinking water sources by UNICEF and WHO. In the census of 2011, tap water from treated source was further specified and covered well was also included in the ‘safe’ source category. Most of these 'safe' or 'improved' sources are groundwater-based, but according to recent government statistics, 71,077 rural habitations in India are drinking water quality affected due to arsenic, fluoride, iron, nitrate salinity, etc. primarily in the groundwater. Absence of a drinking water source or that of a ‘safe’ source within or close to home causes great hardship to women, children and sometimes men, who are forced to traverse long distances. Women and girls often carry water manually, balancing pots over heads, shoulders or waist, sometimes carrying even multiple containers and making multiple trips a day. On the whole, this drudgery may cause loss of productive time, hamper children’s education, increase the risk of physical injuries, and even increase monthly family expenses. Consumption of contaminated water may cause serious disease conditions such as arsenicosis, fluorosis, cancer, diarrhea, and typhoid. All this may interfere with enjoyment of human rights, notably health, education, livelihood and socio-economic wellbeing in general, ultimately restricting rural communities from making progress along the path of sustainable development. The title photo depicts men hauling drinking water buckets at dawn up to their village located on a hilltop in district Zunheboto, Nagaland.

Scooping out scanty drinking water from an unprotected spring in Zunheboto district, Nagaland

Nagaland is a hilly state where villages are mostly located on hilltops, making drinking water procurement a significant challenge for the greater part of the year. This is due to drying up of hill springs which used to be harnessed for this purpose with increasing deforestation, changing land use pattern, and climate change. As a result, soon after the monsoon, water needs to be collected from distant springs located down the hill, causing much hardship for women, men and children who have to carry heavy water loads up the steep hills. The water is mostly procured from open spring-fed tanks which slowly recharge through the night, yielding scanty water in the morning, which further makes the water collection process time consuming. Also, these sources are often open and unprotected, and the practice of water collection unhygienic because the scanty water may be scooped out by stepping into the source. All this expose the water to risks of microbial and physical contamination.

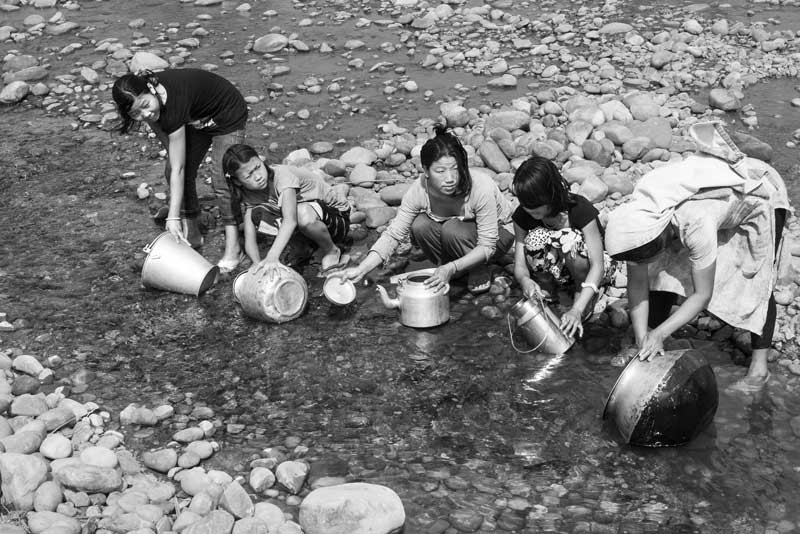

Fetching water from a mountainous river in East Siyang district, Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh is a state with plenty of rainfall, but access to drinking water for rural households can present acute challenges, especially during the lean season. The Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) has laid down piped water supply schemes for facilitating drinking water supply in a number of village clusters, by tapping local springs as the source. However, while during and immediately after the monsoon season, water is plenty in these systems, the spring source itself becomes scanty or even dries up afterwards. This reduces water availability in the scheme, and hence villages don’t get enough water, forcing women and children to access the rivers, streams and other sources outside the village.

Carrying drinking water collected from a distant spring located down the slopes of Himalayan mountains in Tehri Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

Uttarakhand is a predominantly hilly state where groundwater occurs mostly in fissures and fractures, emerging as springs. The unprotected springs, locally known as ‘gadera’ in Tehri region, have traditionally been the most important drinking water source in the mountains, but due to increasing population pressure, land use changes, deforestation, and climate change, many of these springs are drying up. To solve the problem, the government has installed handpumps along roads near villages, but the water smells of iron. Further, while the water yield during monsoon is good, in the lean season, pumping becomes harder as the water table drops, ultimately even drying up. In such circumstances, women and girls have to go in search of water-yielding gaderas, which may be located far away from the habitation, as seen in this photo. According to Census of 2011, over 1,26,000 rural households in this state depend upon springs, rivers, canals, tanks, ponds, lakes and other sources for drinking water, mostly located more than 500 m away from home.

Women carrying drinking water in the scorching sun from a distant source in Thar Desert, Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

In rural Rajasthan, household access to drinking water source within premises is only 21% while about 32% depend on sources beyond 500 meters, according to census of 2011. In the arid western part of the state, such as in districts of Jaisalmer and Bikaner, the water table is very deep and the groundwater is saline as well as contains fluoride. As a consequence, through ages people have instead depended upon rainwater for drinking which is harvested through surface ponds and shallow wells. These wells are mostly located adjacent to or inside the pond for maximum recharge. Further, for the same reason, such recharge zones are often located outside the village settlement at a good walking distance which could be one kilometer or more. Where government has installed groundwater-based or Indira Gandhi Canal-based piped water schemes within settlements to facilitate access, in many cases these have been rejected for drinking due to poor water quality, and women prefer to fetch ‘sweet’ drinking water from ponds or shallow wells despite the hardships entailed.

Women filling pitchers with drinking water at a distant shallow pond near agricultural fields in Kutch district, Gujarat

In Kutch district of Gujarat, groundwater as well as the soil is highly saline. As a result, water in the village wells is often saline. In the absence of any other water source, people are forced to fetch drinking water from sources based on rainwater. In this photo, women are seen collecting drinking water from a distant small shallow pond near the agricultural fields. Since the pond is recharged with rainwater, the water is sweet but it may be biologically as well as chemically unsafe, by virtue of being open and unprotected which can make the water contaminated due to agricultural runoff, animals, and other sources.

Taking unsafe drinking water from a handpump submerged under flood waters in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Bihar is the most flood-prone state in the country with about 73% of the area annually affected by floods. Floods bring devastation in rural areas by physically damaging settlements, inundating cultivated fields, and causing death of animal and human populations by drowning. Very importantly, floods also bring a long-drawn negative impact on the access to safe drinking water, making water supply sources physically inaccessible through submergence, and bringing quality degradation of the supplied water. This may be in biological as well as chemical terms, since sewage, industrial effluents and even solid waste from rural and urban areas all mix and flow, also recharging the groundwater-based sources like handpump and well. Consumption of contaminated drinking water exposes affected villagers to risks of water-borne diseases such as gastro-enteritis, typhoid, cholera, leptospirosis and hepatitis A. The 2013 flood in Bihar affected about 6 million people living in 3,768 villages in 20 districts.

Collecting weekly water ration in a village in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

According to the census of 2011, there exist 79,115 rural households in Delhi, out of which about half are dependent upon handpump, tubewell, tapwater from untreated sources, ponds, lakes and other sources. In some areas including the South-West district, the groundwater quality is poor with salinity as well as fluoride above the permissible limit of 1.5 mg/l. This makes groundwater-based water supply sources unsuitable for drinking. In order to fulfil the drinking water needs of such affected rural habitations, the government supplies water through tankers. However, the tanker supply is only once a week, which poses great hardships for the people, particularly women who have to fill large containers and also arrange to transport these back home from the water collection point. Further, quality of the water supplied by the tankers is not reliable.

Fetching drinking water from a distant safe source across Kolleru Lake in West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh

Kolleru is one of the largest freshwater lakes in India, located in Andhra Pradesh which used to provide clean, sweet and odorless water suitable for drinking even quarter of a century ago. However, the proverb “water water everywhere but no drop to drink” amply describes the pathetic situation of the inhabitants of dozens of villages in and around the lake. These villagers are deprived of access to safe water due to large scale pollution of the lake as well as the groundwater recharged by it. The groundwater is saline, and contaminated with fertilizers, pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals, mostly resulting from large scale paddy cultivation and aquaculture in the lake bed. In these circumstances, residents of the affected villages have to turn to distant sources, including deep tubewells and RO plants, which may incur substantial additional costs for transportation and purchase of the water. The women in this photo procure safe drinking water from a safe source located across the lake in a distant village, commuting by boat.

A pregnant rural woman carrying multiple loads of drinking water from a well across a busy motorable highway in Nashik district, Maharashtra

According to Census of 2011, the access to drinking water source within premises iin rural Maharashtra s only about 43%. However, a recent evaluation study of rural water supply in Maharashtra reveals that a good number of piped water schemes are either non-functional or partially functional due to poor maintenance or low water yield especially in lean season. Even many handpumps run dry during summer. On the quality front, salinity, fluoride, iron and nitrate are reported in groundwater in many districts. Such circumstances force women and men to undergo the hardship of fetching safe drinking water from distant sources. In the absence of a sustainable and safe drinking water source close to home, this pregnant lady in the photo is seen putting her life at great risk by carrying multiple water loads across a busy highway.

Carrying family’s drinking water ration for the day in Bangalore Rural district, Karnataka

In Karnataka, many villages possess piped water supply schemes that are groundwater-based. While these schemes increase drinking water access, safety of the water yielded is a grave concern as 11,013 rural habitations are reported by the government as quality-affected due to presence of fluoride, salinity, nitrate, iron, and even arsenic in the groundwater. Moreover, even where the quality is good, poor maintenance and erratic power supply render these inoperational. The woman portrayed in this photo is fetching water from a standpoint near Hessarghatta Tank’s recharged bed due to a contaminated water source in her village. Sometimes children, men as well as women in such villages also undergo the hardship of procuring drinking water from deep irrigation tubewells located far away in the agricultural fields.

In the absence of a drinking water source in their settlement, girls collecting water from a hilly forest stream in Chittoor district, Andhra Pradesh

Access to safe drinking water can be a problem for communities living in comparatively isolated pockets. The girls portrayed in this photo reside in a small habitation nestled in the forests where access to safe drinking water sources has not been made available. Consequently the families have to procure drinking water from a forest stream. While there is no problem in terms of availability, significant concerns exist regarding physical access since water has to be carried over a considerable distance through the rugged forested terrain. Further, snakes, scorpions, carnivorous animals, etc. pose physical threat while carrying water through the forest. Also, water quality is an important concern due to the open nature of the source and the manner of handling since water is collected by physically entering the water body.

Collecting scanty drinking water from an unprotected source near Tirap open-cast coalmine in Makum Coalfield, Tinsukhia district, Assam

In the coal mining areas, such as in Makum Coalfield in Tinsukhia district, Assam, mining activities may displace village communities from their original locations, also disturbing their drinking water access. Deforestation as well as dewatering of mines reduces recharge of underground springs as well as groundwater. In the rural settlement portrayed in this photo, there exist no perennial and safe drinking water sources, as a result of which inhabitants are forced to procure drinking water from an unprotected water source located downhill which is recharged slowly by water trickling from the surrounding rocks. During lean season, the rate of recharge in such sources is extremely low, as a result of which only a couple of containers can be filled at a time. During peak summer, such sources can completely dry up, leaving people to the mercy of water tankers.

Transporting home containers filled with ‘sweet’ water brought from agricultural fields in Fazilka district, Punjab

Green Revolution undoubtedly transformed Indian economy, and Punjab came to earn the honor of ‘bread basket’ of India. However, during the last 2-3 decades, the water resources here have come to be irreparably damaged, leading to public health epidemics. Increasing contamination of water resources due to overuse of fertilizers, insecticides and pesticides have ended up transforming the state’s Malwa Region from ‘Cotton Belt’ to ‘Cancer Belt’, particularly in districts of Fazilka, Bathinda, Muktsar and Mansa. Besides high salinity, other contaminants present in the groundwater include fluoride, nitrate and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like DDT, aldrin, dieldrin and heptachlor. While the presence of other contaminants is not detectable through taste, smell or color, saline water is rejected for drinking due to objectionable taste and the inability to quench thirst. In many villages in this region, handpumps and tubewells in or near village settlements produce saline water. As a result, many households are forced to undertake the arduous task of procuring ‘sweet’ drinking water from shallow handpumps located far away in the agricultural fields. These handpumps are recharged by irrigation canals, significantly reducing the salinity.

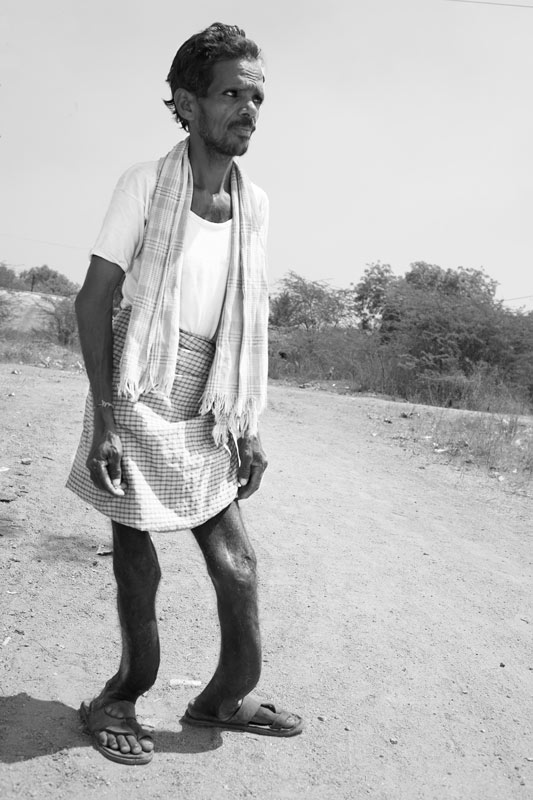

A 35 years old man affected by acute skeletal fluorosis due to fluoride-contaminated drinking water in a village in Nalgonda district, Telangana

In rural India, dependence on groundwater for drinking purposes is as high as 90%, but contamination of groundwater with chemicals like fluoride and arsenic is rampant. According to government sources, total of around 230 districts in 19 States across the country have come in the grip of fluorosis primarily due to high level of fluoride in the groundwater. According to latest government records, the number of drinking water quality affected rural habitations in Telangana is 1,197 located in nine out of 10 districts. Most of these are affected by high fluoride in groundwater. Dental and skeletal fluorosis is rampant in the state with Nalgonda as the worst hit district having fluoride levels in the range of 5-15 mg/l or even higher. In 2001, the official count of patients in the district was already around 650,000, out of which around 75,000 were affected by severe skeletal fluorosis.

A rural lady’s feet affected by hyperkeratosis due to prolonged consumption of arsenic contaminated water in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Groundwater in the states of Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Assam, Manipur, Chhattisgarh and Punjab is contaminated with arsenic, at levels higher than 0.01 mg/l (the maximum permissible limit defined by WHO) or 0.05 mg/L (the permissible limit defined by Government of India). Arsenic is a known carcinogen and its presence in the groundwater poses a significant challenge in rural areas because the common drinking water sources - handpump, tubewell and even many piped water schemes - are based on groundwater. In Bihar, arsenic contamination in groundwater is reported from 17 districts out of 38. Arsenic poisoning, also referred to as ‘arsenicosis’, commonly manifests as skin pigmentation and keratosis (hardening of the skin on the palms and soles). It may lead to skin cancer, and other forms of cancer, such as of bladder, kidney and lung, besides causing respiratory diseases, vascular diseases, neuropathy and liver fibrosis. Prolonged continued exposure can ultimately result in death. In Bihar >10 million people are exposed to the threat of arsenicosis, mostly from rural areas.

Rural water challenges have often been expressed as an ostensibly simple problem of lack of access to safe water. However, as this photo story reveals, the challenge is actually much more complex and multi-facetted. Absence of drinking water sources within or close to rural habitations undoubtedly poses challenges in many areas, but even where 'improved' drinking water sources do exist, there is no guarantee of sustainable access to safe water. In many places, hardships may linger due to lack of water availability in the installed sources, or damaged and poorly maintained infrastructures. All these situations cause hardships to women, children and sometimes even men by forcing them to traverse long distances in search of drinking water for themselves and the family. Further, water quality is an important issue. Presence of an ‘improved’ water source may not always guarantee access to ‘safe’ water, because groundwater – the water resource primarily feeding the rural water supply systems - is contaminated in many places, chemically as well as biologically. Salinity and excess of fluoride, arsenic and nitrate in groundwater are leading to formidable health challenge for millions of rural residents. Poor water quality due to microbial contamination is also significant, during floods and otherwise. According to one estimate around 37.7 million Indians are affected by waterborne diseases annually, 1.5 million children are estimated to die of diarrhea alone and 73 million working days each year are lost due to waterborne disease. The resulting economic burden is enormous - estimated at $600 million (over 5 billion Rupees) a year. According to Down to Earth, rural people in India spend at least Rs. 100 ($1.55) each year for the treatment of water/sanitation-related diseases. According to the Government of India, this adds up to Rs. 67 billion (over $1 billion) annually, which is just Rs. 0.52 billion (approx. $8 million) less than the annual budget of the Union Health Ministry and more than the allocation for education by Government of India. To these figures, health burden resulting from injuries caused by carriage of heavy drinking water loads, lost productive times and missed education can be further added. In many instances, affordability becomes an issue as payments for buying safe water or transporting it across long distances adds up. Lack of access to sustainable and safe drinking water sources close to home ultimately end up restricting many rural women, men and children from enjoying their basic human rights, particularly to water, health, education, livelihoods and overall development. This in turn seriously hampers sustainable development of rural communities. There is need to examine the rural water challenges from a micro-level perspective, considering different eco-climatic contexts, hydrological regimes, socio-economic development patterns etc., and urgently address the real key issues, integrating the quantitative and qualitative dimensions.