Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Status of the Human Right to Water in Delhi

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 June, 2019

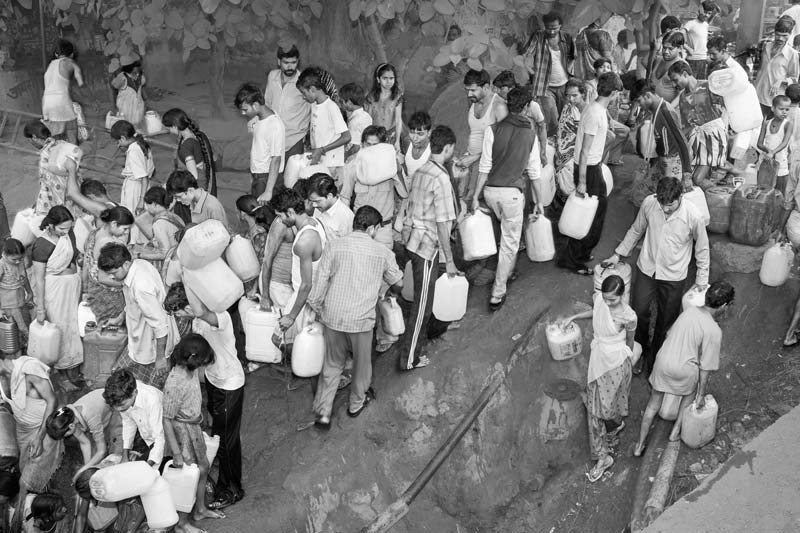

In rapidly urbanizing India, the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015) obliges the government to make cities and urban settlements sustainable and ensure that no one is left behind in access to safe and affordable drinking water. This, in turn, calls for universal realization of the human right to water, which according to the UN framework, entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The norms and goals set up in India within the scope of the human right to water framework were highlighted in the story dated 16 April 2019, and an overview of the status of realization of the right in the country was presented in the story dated 15 May 2019. This photo story probes deeper into the status of the human right to water in Delhi, officially known as the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD). As per the Census of 2011, Delhi is home to about 17 million, and production and supply of drinking water in the city is the responsibility of the Delhi Jal Board. This public water utility claims to supply 227 litres (or 50 gallons) per capita per day (lpcd) of filtered water to Delhi's residents, through an average piped-water supply for 2-3 hours a day. However, according to independent research studies, only up to 70% of the city's population is covered by pipeline connections, and even for them the availability is unreliable because 40-60% of the treated water is lost as leakage or pilfered, as noted by a CAG report from 2013. Thus, Delhi Jal Board is not able to upkeep the service level benchmark (SLB) of 135 MLD set by the Government of India, and further, falls short of the standards of 24 hours supply and coverage at 100%. Many among the 1.8 million slum residents (as recorded in the Census of 2011) and the unspecified populations residing in more than a thousand unauthorized and resettlement colonies lack individual piped water connections. Thus, the 'availability' norm for realizing the human right to water remains unfulfilled. Regarding the human right to water norm of access to 'safe' water, Delhiites face serious challenge. While Census figures of 2011 show that as many as 828,892 households lack access to treated tap water, even the supplied 'treated' water has quality concerns due to presence of iron, ammonia, fluoride, salinity and microbial contamination. Moreover, those who depend on alternate sources such as water tanker, handpump and tubewell, are also exposed to the risk of consuming unsafe water. The third human right to water norm about physical accessibility to sufficient, safe and acceptable water without discrimination stands violated too. According to the Census data, 33.5% of Delhi households in general, and 53.4% slum households in particular, lack access to treated tap water at home, besides the unspecified populations residing in the unauthorized and resettlement colonies. All these people have to either depend upon alternate sources at home producing water of unreliable quality and/or inadequate quantity or procure such water from external sources. The fourth human right to water norm about affordability of water similarly presents difficulties for Delhiites. Slum dwellers and the residents of unauthorized and resettlement colonies spend large sums of money in buying water from vendors, tankers or alternate sources while unreliable water quality forces even those with piped connections to install expensive water filters or buy bottled water in pursuit of safe water. The fifth norm of non-discrimination remains unfulfilled in multiple ways, such as unequal access for poorer residents, inequitable supply among different parts of the city, the drudgery of women and children especially in the deprived urban areas, and lack of participatory forums for the residents. The final norm regarding human right to water is information accessibility, which too remains significantly violated as the people remain poorly informed about aspects like water supply disruptions, water quality challenges and means of contributing to water sustainability in the city. Against this backdrop, this story will make an in-depth exploration of the realities regarding enjoyment of the human right to water in Delhi. Though the NCTD comprises urban as well as a few rural areas, this photo story focuses on the situation prevailing in only the urban areas. The title photo depicts how water becomes everybody's business in the midst of the day in an unauthorized colony when, irrespective of age and gender, they must scuttle to catch every drop of water that becomes available for a short while through a pipeline leakage nearby.

Women and children in an unauthorized colony waiting endlessly for the Delhi Jal Board water tanker to arrive

The Delhi Jal Board claims to make available 820 million gallons per day (MGD) of filtered water to the residents of Delhi through an efficient network of water treatment plants, booster pumping stations and more than 14,000 kms of pipelines. Topped up with about another 100 MGD drawn from ranney wells and tubewells much of which is also distributed through pipelines, the overall piped water supply still falls short of the estimated demand in the city at the SLB of 135 lpcd. More importantly, the water pipeline network still excludes about 19% of the city's households, as per the Census of 2011. These include households in hundreds of slums and unauthorized colonies, largely occupied by lower-middle class and poorer sections. According to a Perceptions Survey reported in the Delhi Human Development Report, 2013, water is among the biggest challenges for residents of these colonies. Delhi Jal Board caters to the needs of residents in these two kinds of settlements through alternate solutions, the most important being supply through water tankers. The Delhi Jal Board tankers are supposed to supply water at multiple points in the city following a regular schedule, which in recent years, is claimed to be supported by a GPS-based monitoring system for greater efficiency and transparency. Despite these measures, Delhi Jal Board's tanker water supply is highly irregular and uncertain, making people wait long hours, giving up other important daily chores, including income-generating activities. In the photo above, women in an unauthorized colony are seen to be waiting for the tanker in the midst of the day, neglecting livelihood activities and necessary household chores. Children are also seen waiting along with their mothers missing their school, because procuring water from the tanker - a labor-intensive task requiring multiple helping hands - holds the topmost priority in the family.

Men and children anxiously awaiting arrival of the water tanker around 10 o'clock in the morning

Water supply in the areas not covered by pipeline network is provided through a fleet of more than 1,000 tankers, owned by Delhi Jal Board or hired on contract. A detailed supply schedule is available on their website, containing meticulous details such as vehicle number, location, distribution days, etc. Despite these preparations, tanker water supply continues to pose a regular challenge to the residents. It is wasteful of time, because sometimes residents have to keep waiting for hours instead of going out to work, as is shown in the photo above, and even then, the supply is not guaranteed. At the spot depicted here, the tanker was supposed to have arrived at 9.00 in the morning, but even at 10.00, there was no sight of it. Absence of the tanker at stipulated time commonly implies diversion of the supply to other unauthorized recipients, obviously for a good price, as is alleged and feared by the residents everyday until the tanker actually arrives. Seen from the human right to water perspective, this directly thwarts the norm regarding 'availability' and 'physical accessibility' to water, because there exists no alternate water source for these deprived people. In general, too, the tanker water schedule is violative of the 'availability' norm because at several points the distribution frequency is as low as only once or twice a week. One can well imagine how by collecting tanker water only one or two times a week, the members of a family can access 135 lpcd? Moreover, the 'information accessibility' norm for enjoying the human right to water also stands thwarted because the information about water tanker schedules published on the Delhi Jal Board website is inaccessible to many due to lack of necessary knowledge and infrastructure, and Delhi Jal Board has failed to systematically communicate these schedules to the concerned residents through other channels.

Hurrying up to the top to secure a share in the tanker water

According to the residents of the colony served by water tanker as shown here, it takes them 30-60 minutes daily to fetch water from a tanker, sometimes extending up to two or three hours, if the waiting time for the tanker is long. However, collecting the water from a tanker presents a huge challenge that can be overcome only through organized family effort. As soon as a tanker arrives, young and energetic boys climb up to insert the pipe and suck the water out, as is shown in the photo above. However, this is extremely risky as tankers often stand on the side of motorable roads with buses and cars plying, and an accidental fall can become fatal, thus thwarting the right to health and well-being. Residents of the colony depicted here reported that several such accidents have occurred in the recent past. For families that lack physical support, or become late in arrival on-site, it implies thwarting of the human right to water norms of 'availability' and 'physical accessibility' as they are left deprived of water access. Alternately, this makes their exercise of the right 'unaffordable', because then they are forced to buy water from others who have collected extra or from other sources.

Rush to collect the scanty water provided by a Delhi Jal Board water tanker

Though Delhi Jal Board supplies water to the uncovered settlements through multiple tanker trips every day, the quantum of water supplied is manifold short of the actual demand. According to a CAG audit report from 2013, a population of about 3.3 million was supplied with more than 1,000 million gallons of water through tankers during 2011-12 in Delhi. This meant an average supply of barely 3.82 lpcd, as against the SLB of 135 lpcd. With a rapidly increasing population in the slums and unauthorized colonies in Delhi, one can well imagine that the figure must be increasingly worsening. After a tanker arrives, 50 or more pipes may be inserted simultaneously as shown in the photo above, which empty out the tanker within minutes. Since a large number of households depend on a single water tanker, there is generally great rush when it arrives, and since no one wants to be left behind, people tend to hurt each other physically when struggling for water and fights around the tankers are a common sight. Further, even the quality may be unreliable, since tankers are often filled with groundwater extracted from the Delhi Jal Board tubewells or its ranney wells, which may be contaminated with fluoride, nitrate, or salinity. Thus, the water tanker may become the source of conflict in a colony, besides violating various human right to water norms such as 'availability' and 'safety'.

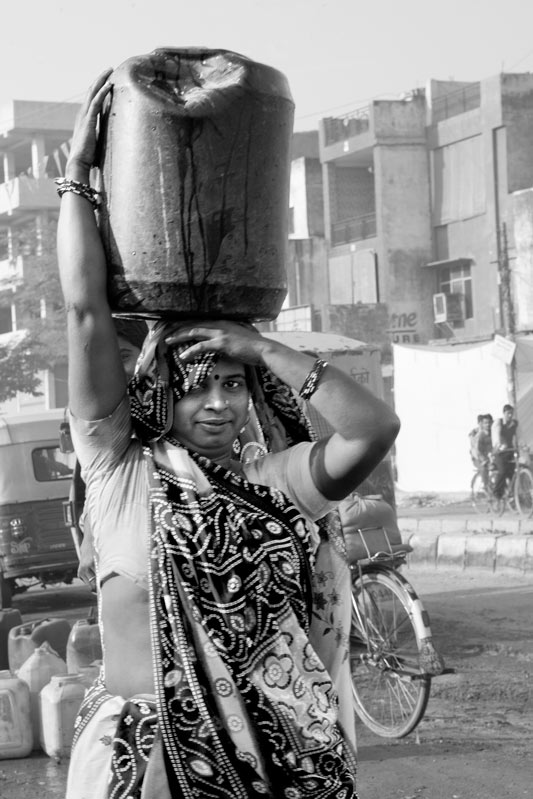

Hauling water collected from a tanker

The households that depend on the tanker supply commonly collect water in large containers with capacities ranging between 20-100 liters. Hauling these from the collection point to the house, which is often more than 100 m, is an arduous task and people have to adopt different alternatives for this purpose. It is a common sight to see women and girls carry headloads of water in the range of 20-50 liters as shown in the photo above, while men and boys often transport larger containers upto 100 liters on cycles and other modes of transport. This situation contravenes the norm of 'physical accessibility' within the human right to water framework, because of the great distance and the bulk of water to be transported.

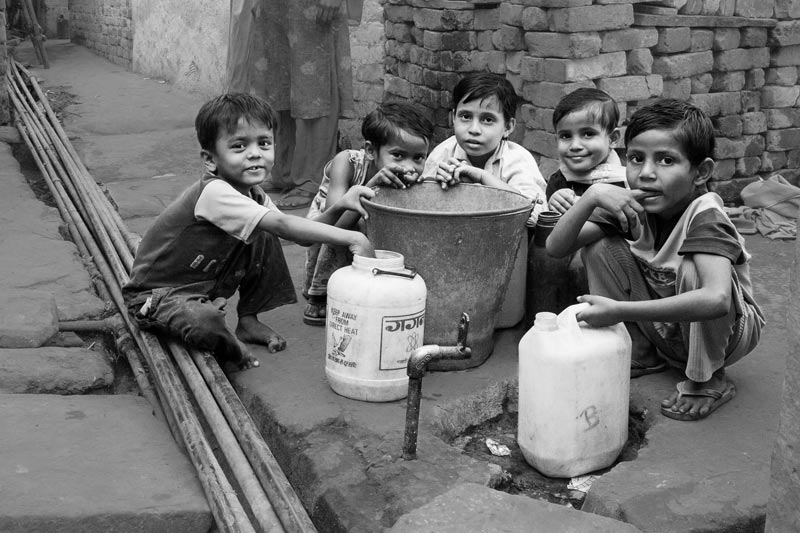

Left without water after a long wait at a tanker water distribution point in a slum

Even a regular water supply through tankers brings no guarantee that the targeted households will be served adequately. Delhi Jal Board claims that a tanker's distribution points are selected in consultation with local area representatives for equitable water distribution, but residents complain that this process instead skews the distribution since the representatives may end up designating a distribution point close to their own house or at a point where access for own family and supporters gets prioritized. Further, in general, the number of takers at the distribution points is always very large while the amount of water transferred is little. In the photo shown above, several children who have left their studies or compromised with their playing time to fetch water from the tanker, are forced to remain empty-handed. At this distribution point, extra water remaining in the tanker is supposed to be filled into a tank installed there for later use during the day. However, this target is never reached, since the tanker water gets finished even before everyone in the queue can get access to water. Thus, the process of tanker water distribution adopted by Delhi Jal Board ends up in violation of the 'availability' and 'non-discrimination' norms of human right to water.

A public water hydrant shared by multiple households near a slum

Apart from water tankers, the settlements lacking household-based pipeline supply are served through public water hydrants. According to government sources, there existed 11,533 water stand posts in slums and unauthorized colonies in 2001. Over the years, the number of such public points has grown manifold. However, despite several new installations, the water demand at public standposts still exceeds the supply and the supply itself remains erratic. The public standpost shown in the above photo is located outside a slum along a main road. However, the water supply is irregular and ends in just 30-45 minutes. Consequently, conflicts are common and still, at the end, some households may fail to access water. Sometimes, the conflicts at public water hydrants can turn violent, as was reported in September 2015, when a man died in a water conflict at a public standpost. Moreover, for some households, the distance between the source and residence is long, making transportation of the containers a challenge. Thus, it is obvious that despite installation of public water hydrants as an option, the human right to water norms of 'availability', 'physical accessibility', and 'non-discrimination' may remain thwarted, besides threats to life and well-being.

Waiting for water at a public tapstand in an unauthorized colony

Apart from the water tankers and public water hydrants provided by Delhi Jal Board, certain slums and unauthorized colonies are also served by local piped water networks. A good number of these are illegal, because these are based on either tubewells installed by private operators without the mandatory authorization of Delhi Jal Board or have been created by the residents themselves with local political patronage by illegally puncturing a water main nearby. Many illegal tubewells operating in unauthorized colonies that allegedly supplied piped water to the residents at an exorbitant price of Rs 1,000-1,500 (approx. 14.4-21.6 USD) or more per family per month have been taken over and being maintained by Delhi Jal Board in the recent years. One such piped water network is shown in the photo above, where the supply hours are uncertain and children as young as 4 or 5 years old are recruited in queue in the evening, so that parents can undertake other essential chores. Also, when it arrives, the water is at low pressure and scanty. Thus, not only is the 'availability' norm of human right to water hindered for everyone, but children's rights to play and leisure time, and hence healthy growth and development is thwarted.

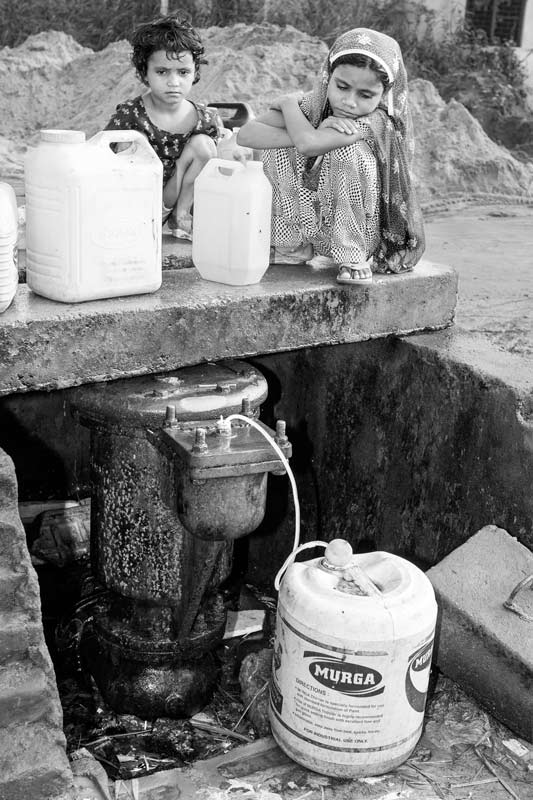

Filling containers with water trickle from a local piped water network

The local piped water networks in slums and unauthorized colonies generally provide scanty water of unreliable quality, and the supply hours could be odd. In the above photo, water has come late in the evening, at a low pressure and the duration of supply would be short. Besides, this and many other local piped networks supply untreated groundwater, which could pose health hazard due to contamination. According to Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), the groundwater in many parts of Delhi has high concentrations of fluoride, nitrate, iron, and salinity. besides, arsenic has also been reported in some areas recently. Figures from the Census of 2011 show that more than 6% households in Delhi are dependent on untreated water from piped networks. Thus, while locally operated piped water networks may facilitate water access, the criteria of 'adequacy', 'quality', and 'affordability' still remain a challenge and cumulatively end up thwarting enjoyment of the human right to water.

Procuring water from a valve leakage at a water main

For those Delhiites who lack access to Delhi Jal Board's or even private piped water networks and are also excluded from tanker supplies and public water hydrants, procuring water is a huge everyday challenge. They must spend hours in search of water, depending upon odd sources such as leakages from water mainlines and valves. One such leaking valve is shown in the photo above, which has been improvised by inserting a thin pipe to channelize the spilled water into containers. During the hours of water supply through the valve, many people queue up to collect the scanty leaking water. Presence of the young girls at the leaking valve during morning hours symbolizes the violation of children's right to education, health and well-being for enabling water access, because assisting parents in collecting water by reserving a position in the long queue takes priority over anything else. The irony is that despite all efforts, access to adequate water may still not be ensured.

Collecting potable water as a trickle from a city mainline leakage

Several households located in slums, unauthorized colonies and resettlement colonies lack access to adequate and reliable water. Such households must make alternate arrangements for procuring water, one solution being shown in the photo above. Here, the trickle from a leakage at a water mainline that carries treated water to a planned colony is tapped during the supply hours by residents of a nearby unauthorized settlement for procuring drinking water. The task is time-consuming, and children are often deployed on the mission since parents may be engaged in other daily chores. In the process, children often lose their valuable time for play or leisure activities and may even have to miss school. Moreover, the amount of water collected may remain inadequate for the family, thus still causing violation of the human right to water in terms of 'availability' and 'physical accessibility'.

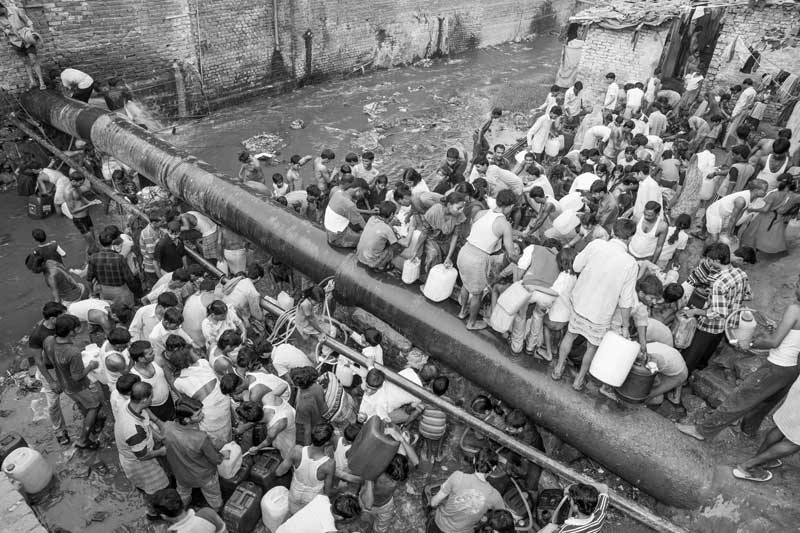

Water being procured from a pipeline leakage near a cluster of slum and unauthorized colonies

Collection of water from pipeline leakages presents many faces in Delhi. In the case shown in the above photo, very few have a water source at home which can facilitate enjoyment of the human right to water. For a majority of the others, dependence upon leakage from a pipeline that passes close by is the only solution. At the joints of the pipeline, several plastic pipes are meticulously inserted to channelize the leaking water into containers of various shapes and sizes. The amount of water conveyed by a pipe is small and filling a container thus takes time. However, the exercise needs to be completed by all dependent households during the short period of supply in the pipeline which is just about one hour in the afternoon. Since this is a time when the people should actually be at work, water is collected by many at the cost of gainful employment. Those that cannot be present, are forced to procure or even buy water from other sources. And as with other sources as described before, there is no guarantee that everyone will be able to collect water in general and in adequate quantity in particular.

Rush for water collection at a pipeline leakage situated across a wastewater drain near a cluster of slum and unauthorized colonies

When water as a basic necessity remains unavailable through regular means, people are forced to explore every possible opportunity, oblivious of the setting where it is located. The pipeline described in the previous photo is located across a wastewater drain, but despite the location, there is always great rush on both sides of the pipeline as seen in the photo above. Hundreds of men, women and children try to procure their share at the same time, most of them using the leakage points that can be accessed on the ground at the fringe of the drain. For this purpose, they climb on to the pipe which becomes wet and slippery, making many slip and fall. Even the terrain here is undulating and slippery, and the residents report that several women, men and children have got seriously injured in the past due to slipping and falling from the pipe or otherwise while carrying heavy water loads. Further, given the rush on the fringe and the limitation of time, some people even descend into the drain for filling their containers. The wastewater in the drain smells foul, making the environment unhealthy and therefore a pertinent question is: can the water collected from inside or the fringes of this drain be considered as 'safe'? How well are the availability, physical accessibility, non-discrimination, and safety norms of human right to water fulfilled in this case?

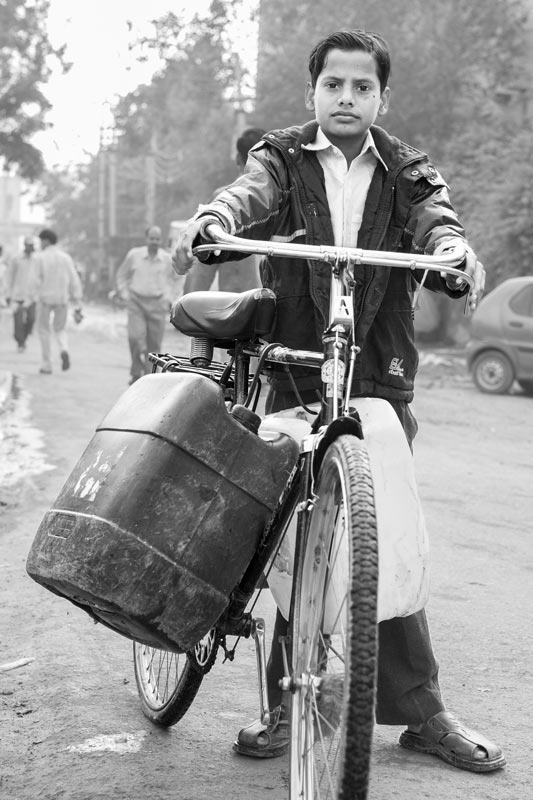

Fetching loads of water from a distant source

When people cannot find any water sources within or near their settlements, they must procure water from a distance that could imply greater uncertainty and unreliability in terms of quantity as well as quality. The quantity of water procured would depend upon the manpower and the means of transportation available, besides the quantum of availability at the source itself, while the quality may never be assured. Moreover, the entire family may become more engaged in water procurement tasks for longer durations, thereby hampering children's education and leisure, and women's and men's productive opportunities. In some cases, water needs to be purchased that adds to the household budget. In the photo above, an teenager is seen carrying home heavy loads of water collected from a distant source.

Transporting water purchased from a distant piped water network

Drawing contaminated groundwater in a resettlement colony

Many slums in Delhi have been relocated as 'resettlement colonies' which are legal but not included in the central piped water infrastructure. Instead, the people have been forced to install individual handpumps, as shown in the photo above. While groundwater is plenty in the floodplains of Yamuna river where much of the resettlement has been done, water quality is a huge problem. Groundwater is highly contaminated because of release of untreated sewage laced with chemicals from industrial effluents into the river. Residents in these colonies complain that they often suffer from gastro-intestinal ailments on consuming handpump water. However, no information has been imparted by Delhi Jal Board or any other government agency about the compromised groundwater quality in the area, and measures needed to address it. Ill-health reduces people's work efficiency, makes children miss school and adds medical expenses to the already impoverished economies. For securing water quality, the human right to water norm of 'affordability' gets further violated, because then 'safe' water needs to be purchased.

Bottled water as a means of water security for Delhites

In many areas in Delhi, water is either inadequate or unsafe for drinking. In either case, the deficiency for drinking water is fulfilled by many through purchase of bottled water. Bottled water comes in smaller sizes as well as 20 liters jars. Many households in the city use these bottles and jars for drinking water security round the year. Their price varies according to the brand - while local brands are cheaper, with 20 liters jars selling at Rs. 10 (approx. 0.14 USD), there are also more popular brands that sell at Rs. 70 (1.01 USD) or more. Even Delhi Jal Board sells its own brand of bottled water. Though access to bottled water in no way guarantees access to safe water, people narrate that they have no choice because either Delhi Jal Board's supplied quantum is too little, or the quality of Delhi Jal Board's piped water and tanker water supplies as well as Delhi's groundwater through tubewells and handpumps is widely seen as unreliable. Bottled water is not easily affordable by all, and especially makes the poor compromise with other necessities of life, adversely affecting their quality of lives through multiple pathways.

Bathing on the banks of river Yamuna with polluted water

When access to drinking water becomes a problem, water for other personal and domestic uses poses an even greater challenge. In the absence of appropriate and adequate sources at home, people may be forced to carry out activities that require bulk use of water at the source itself. The man bathing in the polluted water of river Yamuna, shown in the photo above, lives in a slum nearby where access to water for fulfilling even drinking water needs is difficult. Therefore, despite knowing that the river water is polluted, and ignoring the garbage on the banks, he regularly fulfills his bathing and washing needs at the river itself, because in his words "something is better than nothing".

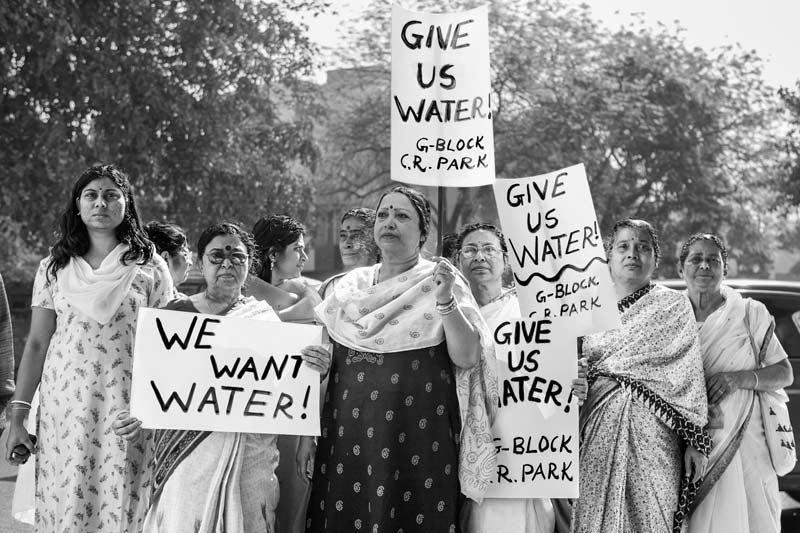

A demonstration for (re)gaining water access in a planned colony

Several studies have found that the distribution of water in Delhi is not equitable across districts, with the peripheral areas receiving lower volumes per resident. Further, residents of the poorer, unplanned, non-regularized settlements receive far lesser amounts, in comparison to the planned areas. However, the people residing in the posh, planned colonies and belonging to the higher socio-economic strata too are forced to live in 'water poverty' in a different form. Though they enjoy access to centralized piped water supply maintained by Delhi Jal Board, they suffer from ailments like sudden disruption of supply due to breakdowns in infrastructure, inconvenient supply timings and low pressure even when, as noted before, Delhi Jal Board claims to provide safe water access to Delhiites at 227 lpcd. In the photo above, residents of a posh planned colony are seen protesting a long-drawn unavailability of water in the piped network, despite having metered connections for which they regularly pay up bills.

An illegally fitted Tullu Pump to lift water directly from the supply line to an overhead tank

The pressure in the piped networks of Delhi Jal Board that supply water in the planned colonies of Delhi is often low to the extent that water cannot be filled into overhead storage tanks. Besides, though the supply is generally regular, the duration is short, between just 1-3 hours a day and the timings are odd in some segments. This takes away people's opportunity of filling enough water to last the family for the whole day. The situation becomes all the more pathetic for the tail-enders who are unable to fill even large drums kept on the ground floor. This is a blatant violation of the 'availability' norm of the human right to water framework, as well as the 'non-discrimination' norm, because the tail-enders are left to suffer more from the water crisis. To improve water access, and increase the storage capacity, people are left with no option but to illegally install motors directly on the line, as shown in the photo above, lifting water from the pipe up into overhead tanks. This makes water more expensive than it is, because electricity bill is added. Since the supply hours are fixed and at some places odd (too early in the morning or during the afternoon), failure to turn on the motor or absence at home during the supply hours could further mean missing the opportunity of accessing water for the day.

Reverse-osmosis (RO) based water purifier at home for accessing safe water

Besides quantity-related woes, water quality is a serious concern in the planned colonies inhabited by the higher income groups. There is general discontent about the water quality, since sometimes the supplied piped water is visibly unclean due to impurities entering from leakages and points of pilferage. In addition, groundwater is added into the piped water supply by Delhi Jal Board from its tubewells and ranney wells, in a context where groundwater has been found and reported to be contaminated with heavy metals, chloride, total dissolved solids, nitrate, fluoride, and trace metals, besides higher coliform count. Delhi Jal Board lacks the infrastructure for adequately treating such chemically contaminated groundwater so as to reach the drinking water standards set by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) or the WHO. Many Delhites residing in the planned colonies thus fail to be secured with safe municipal water supply and end up incurring extra expenditure by regularly buying bottled drinking water or installing water purification systems like the RO shown in the photo above.

This story has presented an in-depth analysis of the status of human right to water in the National Capital Territory of Delhi. It is obvious that the situation is dismal and problems with enjoyment of the right are rampant. As this story has revealed, a large segment of the urban poor that reside in 'informal' settlements - the unplanned and unauthorized colonies and the slums – as well as the 'resettlement' colonies are the ones to suffer from shortcomings in water access in a major way, including quantity and quality challenges. Even many of those inhabiting the planned posh colonies of the city suffer alike. The different pathways leading to the sufferings and the outcomes for the different residents have been illustrated in detail above. As a result, enjoyment of the right to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use remains challenged. Though an exact figure quantifying the extent of the problem is missing, it clearly emerges from the story that for a significant proportion of Delhiites, the different norms essential for enjoying the human right to water as outlined in the UN framework remain unfulfilled, thereby denying the opportunity to enjoy the right. These include the 'availability' and 'physical accessibility' norms which go hand-in-hand, as well as those about 'safety' and 'affordability'. The norms of 'non-discrimination' and 'information accessibility' are also thwarted in different ways. The burden on women and children due to water-related drudgery remains unaddressed for the poorer families, exposing them to health risks as well as hampering children's education and overall development. Problems with water access also lead to increasing poverty because the poor already earn less but end up allocating productive time for water procurement, simultaneously also spending more for the purpose. Even those who are economically better-off suffer from water poverty in different ways.

It is a matter of great concern that despite being the seat of two governments - the Government of India and that of Delhi, and also being the base of several international and UN agencies concerned with the human right to water and SDGs, the status of enjoyment of the right is far from satisfactory in Delhi. The public water utility – Delhi Jal Board – has taken several steps in the recent years to improve the situation of water access in the city. These include measures for improving the water availability through increased water production, upgrading water treatment facilities to improve the quality of supplied water, 'Jal Adhikar' (water right) connections for slum dwellers, improving the tanker water supply efficiency, and initiating drives to regularize illegal water connections in unauthorized colonies. However, the progress achieved under these improvements remain like a drop in the ocean, and the expected outcomes have not yet been reached. As a result, the water woes of Delhiites continue to thrive irrespective of the kind of settlements they inhabit. Problems with enjoyment of the human right to water thwarts the enjoyment of several concomitant human rights by them and poses a great challenge for achieving the SDGs. There is need for Delhi Jal Board to look deeper into the current gaps, redesign the ongoing strategies accordingly and attempt to effectively implement the planned action. Otherwise, women, men and children's human right to water in the capital of India will continue to remain unrealized, in turn thwarting their other human rights such as that to health, education, sustainable livelihoods, and over-all development.