Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Status of the Human Right to Water in Gujarat

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

31 August, 2019

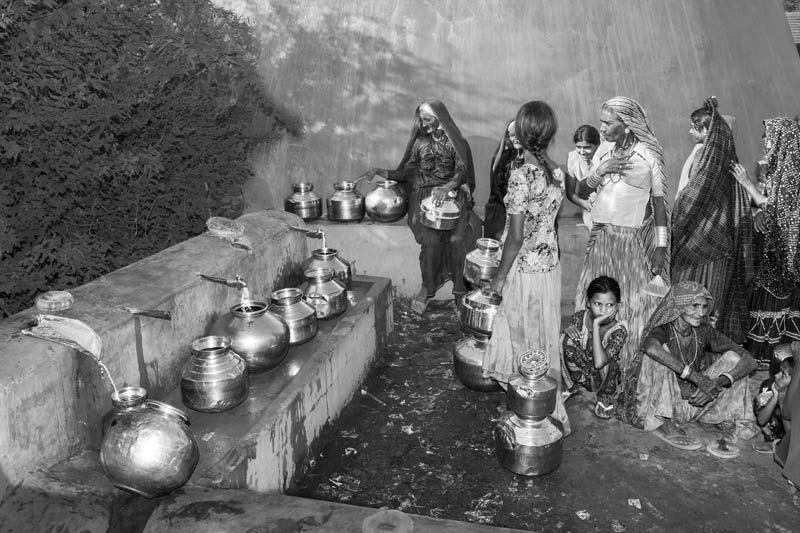

Universal realization of the human right to water is the means to reach the sixth UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) - ensuring that no one is left behind in access to safe and affordable drinking water. According to the UN framework, human right to water entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The norms and goals set up in India within the scope of the human right to water framework were highlighted in a previous story (16 April 2019), followed by presentation of the status of the right in India (15 May 2019) and in the cities of Delhi (15 June 2019) and Mumbai (29 July 2019). This photo story will capture the scenario in rural India, taking a look at the western coastal State of Gujarat which is reckoned by the government as among the five largest State economies of the country in terms of GDP, and also one of the most industrialized ones. In the SDG Index Report, 2018 released by the NITI Aayog, Gujarat has been awarded a full score of '100' for SDG 6 – focusing on Clean Water and Sanitation. In relation to water, a major determinant of this score is the percentage of rural population having safe and adequate drinking water access, which is claimed by the State government to be 100% 'full coverage' at 40 liters per capita per day (lpcd) and 99% at 55 lpcd. More than 72% rural population is reported as being served with piped water supply. These statistics have been acknowledged in the Performance Audit of the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) conducted by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India in 2018. However, despite the rosy picture painted above, there exist strong evidence of serious challenges to enjoying the human right to water in Gujarat. The CAG Report, 2018 notes that over 5% of rural habitations in the State have 'slipped-back' from 'fully covered' to 'partially covered'. The report also notes that in several villages, water was supplied through tankers during the period 2012-2017, which indicates that many so-called 'covered' villages lack sustainable access. Added to this are scholarly and media-based reports from the State as well as field-based experiences of the authors from some of the "fully covered" villages which buttress the fact that access to water for drinking and personal uses is a problem. Further, according to Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), groundwater quality stands considerably degraded in several districts. Despite this, a good number of rural piped water supply schemes are groundwater-based, but the State government does not report any community-based interventions for mitigating the contaminants in the supplied drinking water. Instead it reports quality-affected habitations as 'nil'. Ironically enough, this is the status even when the CAG report, 2018 mentions 422 rural habitations as having 'slipped-back' from 'fully-covered' to 'quality-affected' during 2012-2017. Field observations in some of the affected districts further clarifies the situation since health consequences like fluorosis are significant. Given the above scenario, violation of the human right to water of many rural populations in the State becomes more than obvious, particularly regarding the norms of 'availability', 'safety', 'physical accessibility', 'non-discrimination' and 'affordability'. Looking more deeply into the geographical regions of the State, access to water for personal and domestic use has been a perpetual challenge in the Kutch, Saurashtra and North Gujarat regions which cover about 75% of the land area. This region is characterized by low rainfall, skewed rainfall distribution and recurrent droughts, and the government claims to be even more vigilant in fulfilling the drinking water needs of the people here. Initially, pipeline schemes based on ground- and surface- water were laid down, but in the wake of recurrent water scarcity despite the previous schemes, all villages of Saurashtra and Kutch and all "no source" villages and those affected by salinity and fluoride in North Gujarat are being covered under the Narmada-based drinking water supply project from the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Against such a background, this photo story aims to present glimpses of the plight of the rural inhabitants of Gujarat in realizing their human right to water by focusing on the Kutch region. This region is entirely constituted of Kutch district – the largest district of Gujarat as well as India which is emerging as an important industrial hub of the State. Given its dry and hot climate, low average annual rainfall of 346 mm, and a desert spread over 51% of the land area, Kutch has ostensibly received much government attention. The Kutch villages are claimed to be statistically 'covered' under one or the other kind of water supply schemes, including the recent Narmada-based piped water supply. However, despite all claims, the access to adequate and safe water remains a distant dream for many. The title photo depicts women and girls procuring water from a distant pond in the evening in a village in Kutch district that lacks public water supply. Despite the drudgery and the uncertainty of quality, they are happy that at least there is access to water.

Overhead reservoir and sump to store water for pipeline supply in a village

The Gujarat government has always claimed to be vigilant and sensitive towards the hardship of drinking water faced by the people. The Rural Water Supply Program claims to provide regular, safe and adequate water for drinking and other household purposes to everyone primarily through individual piped water supply schemes and regional/group water supply schemes. The present Rural Water Supply Schemes are designed considering 100 lpcd, based on groundwater as well as the river sources, the latest being from Sardar Sarovar dam on Narmada. The government reports that up to end of the March 2019, 8,911 villages in Kutch, Saurashtra and North Gujarat regions have been 'covered' under the Narmada-based pipeline supply. In Kutch district, where 787 out of 948 villages were identified as "no-source", piped water supply has been as old as five decades, with groundwater as the main source. When piped water supply fails, water is supplied through tankers. To tide over this crisis, 886 villages of the district are to be covered under the new Narmada Canal supply described above and laying of pipelines in a large majority of these villages is now reported as already completed or in progress.

Rush at a public tapstand to collect the scanty water that has arrived after days

Although 100% villages in Gujarat are claimed to be 'fully-covered' under different kinds of rural water supply schemes, there exists no guarantee of water 'availability' in terms of adequate quantity and regular supply, which constitute an important human right to water norm. The CAG Report (2018) identifies low pressure at tail-end villages as an important problem leading to water supply disturbance in Gujarat, besides lack of sustainability of water sources, and inadequate/non-maintenance of water supply schemes. This includes villages under the new Narmada Canal supply. The scenarios reported for Gujarat hold true for villages in Kutch district. In fact, an in-depth research on water deprivation in the district (2002) found that more than 60% of the rural water supply schemes implemented here face severe irregularities in supply due to above reasons. In many villages in Kutch, the pipelines were reported to the authors of this story as supplying water intermittently – only once in several days, one such instance portrayed in the photo above. Also, the pressure is said to be often low, and the timing too short. As a result, even when water arrives, many women and girls fail to procure their share of water from the public tapstands. Further, at some places only untreated groundwater is supplied, which places the users at great health risk in the fluoride-, nitrate- and salinity-affected villages, thus also thwarting the 'safety' norm for enjoying the human right to water.

Father and daughter suffering from dental fluorosis due to prolonged consumption of fluoride-contaminated water

Water quality degradation is a widespread problem in Gujarat, but water supply schemes continue to be widely based upon groundwater sources, without adequate and appropriate mitigation options. According to the CGWB, groundwater is affected by salinity in 20 districts, fluoride in 18 districts, and nitrate in 22 districts, besides iron and other contaminants. In fact, Gujarat is one of the most endemic States regarding fluorosis resulting from consumption of water with fluoride concentration above 1.5 mg/l. In Kutch district, salinity as well as excess of fluoride in the groundwater are significant concerns. Increasing complaints of kidney and gastric problems due to consumption of saline water and dental fluorosis resulting from consumption of fluoride-rich water are reported, as portrayed in the photo above. Fluoride level up to 7.5 mg/l has been identified by CGWB in the district. Unfortunately, according to District Census data, 2011, more than 51% rural households depend upon tapwater from untreated sources, which in a great majority of cases is sourced from groundwater. There is absence of regular monitoring of contaminants in groundwater, and appropriate mitigation options are lacking as was noted by the CAG in its audit report (2018). Such a situation seriously thwarts fulfilment of the second criterion of access to 'safe' water towards enjoyment of the human right to water.

Improvised water collection from a pipeline leakage

'Physical accessibility' of water is another significant norm necessary for enjoying the human right to water. In Gujarat in general and Kutch in particular, physical accessibility continues to be blatantly thwarted despite claim of 'coverage' under rural piped water schemes. As the CAG report notes, non-availability of necessary infrastructure and lack of internal pipeline network in the village deprives residents from accessing piped water within rural habitations. Alternately, villages have been ignored in favor of water supply to industrial units in the neighborhood, because industrial development is an important priority in Kutch district. Thus, pipelines may be found to pass close by villages, but such villages continue to remain parched. In such cases, for fulfilling their water needs, rural residents are forced to improvise access from such available options, an instance of which is shown in the photo above where water leaking from a pipeline on the village outskirts is meticulously collected by women and girls and utilized for personal and domestic uses.

Another example of improvisation – sourcing water from a valve leakage

Given the water scarcity in Kutch region in general, every drop of water is precious. Therefore, in the absence of piped water supply or other sustainable water sources in or near the village, leakages from even pipeline valves are made use of as shown in the photo above. This exercise is time-consuming and hence wasteful of the time and effort devoted. Since water emerges slowly from the valve, a significant amount of time is invested in filling single water pots. This hinders girls' education and prevents women from utilizing their time more productively. besides, tehwater may still remain insufficient for fulfilling various domestic and personal uses. This thwarts enjoyment of the human right to water as well as other concomitant rights.

Drawing water from the valve leakage portrayed in the previous photo

An old woman transporting potfuls of water obtained from a valve leakage on village outskirts

Water for domestic and personal use is a scarce resource in rural Kutch, thanks to ill-covered, ill-managed and inoperational water supply schemes. Women and children as domestic water managers must toil hard to fulfil their water needs irrespective of age and capabilities. This disturbs children's education and lowers women's productive capacities, besides putting their health into jeopardy due to risk of injury in joints, neck and back, and stunted growth in young children. The old woman shown in the above photo fetches water everyday from the valve leakage shown previously, enduring the hardship under the scorching sun at a time when water flows in the pipeline.

Collecting water from the village pond as a result of non-functional rural water supply scheme

Despite the rosy picture of 100% full-coverage of rural water supply in Gujarat, the CAG Report (2018) notes that 1,767 rural habitations 'slipped-back' from 'fully covered' to 'partially covered' during 2012-2017, drying up of water sources and inadequate/non-maintenance of schemes being important causes. It also notes that out of the 945 villages that were newly covered during 2012-2017, 142 were not getting water due to various kinds of technical problems. When pipeline supply becomes scarce, water is sent through tankers, but the availability then becomes as low as only about 14 lpcd and tankers arrive once in a blue moon. Under such circumstances, villagers are forced to fall back upon ponds and other alternate surface water sources in the village, as shown in the above photo.

Collecting water for drinking and personal use from a visibly muddy pond on village outskirts

In many Kutch villages, pipelines have been laid, but as noted before, these schemes may either stand defunct on grounds of lack of maintenance or provide intermittent and inadequate quantities of water. Consequently, women are forced to access alternate sources to fulfil their water needs. Such sources may be located nearer the village but still, as depicted in the photo above, fall short of the quality criterion as is evident from the muddiness in the photo above. Such a situation clearly hampers the 'safety' criterion for enjoyment of the human right to water.

Collecting drinking water of questionable quality from a distant pond

In those instances, where there are no water sources in or near the village, women and girls are forced to traverse longer distances in search of water. They may need to fetch water from distant sources as shown above, which may also be exposed to the risk of contamination, thus thwarting the 'availability', 'accessibility' as well as 'safety' parameters for enjoyment of the human right to water.

En route home with loads of filled-in pots

Traversing a long journey back home with heavy loads of water

In the absence of water sources in the village, women, accompanied by children – both girls and boys – must undertake the drudgery of carrying water from distant sources on a daily basis, irrespective of the season, braving through sun, rain and cold. This may involve walking barefoot across kilometers at stretch with heavy loads of water on the head, waist or shoulders, as depicted in the photo above. Carrying of heavy loads of water over long distances is not only tiring but brings serious health risks of neck and back pain as well as spinal injury. It is also time-consuming as hours may get spent in the task, depriving children from attending school and preventing women from efficiently undertaking domestic chores or engaging in economically productive tasks. All this obviously thwarts the norm of 'non-discrimination' in realizing the human right to water and prevents enjoyment of other concomitant human rights.

A young girl fetching water alone from a distant pond at dusk

Women being primarily the ones responsible for water - a basic necessity for the family - have to ensure adequate water supply at home at all times. Consequently, they have to make multiple trips to the water source during the day, even if distant and at odd hours. Sometimes, young girls are sent instead, especially when it is time for completing other essential domestic chores at home. Traversing to distant sources alone at dawn or dusk, as portrayed in the photo above, may expose women and girls to the threat of physical insecurity, thus thwarting the norm of 'non-discrimination' in enjoying the human right to water.

Procuring water in bulk from a distant unprotected source

In the absence of an operational water supply scheme in the village, it may become unrealistic for women to procure water from outside on a daily basis, because even the nearest water sources may actually be located very far. Under such circumstances, men may lend a helping hand as shown in the photo above, procuring water in bulk that could last a couple of days at a time. Such distant location of water sources is a clear violation of the 'physical accessibility' norm for realizing the HRW. Besides, the process of handling the water itself may introduce contaminants in the collected water, further degrading the water quality., and thereby thwarting the 'safety' norm of human right to water.

Another alternative for securing domestic water from a distant source

In the absence of water supply in the village, consuming water from an unprotected source where the quality may be uncertain

Proceeding to wash clothes at a pond on village outskirts

Water supply in many Kutch villages is limited, particularly in the piped networks. This is often reserved for purposes of drinking and cooking. Further, given the hardships in procuring water from distant sources in the absence of a source close to home, priority is given to fetching of drinking water. Under both these circumstances, for other uses such as washing and bathing, which generally require larger quantities of water, it becomes easier and more efficient to carry out the activity at the source itself, as depicted in the photo above. Though water may thus become available for other uses, the drudgery of going to the source itself is wasteful of time and energy, depriving girls and women of more gainful engagement such as studies or economic activities, thereby hampering their human right to water as well as other human rights.

This photo story has painted a vivid picture of the status of human right to water in the villages of Kutch region of Gujarat – a growing economic and industrial hub of the State. Here provision of regular, safe and adequate water for drinking and other household purposes has been an important priority of the government for decades. However, as the story has revealed, despite its economic growth and assets, and its humanistic claims, it has inevitably lagged in securing the human right to water to its rural populace. More notably, this happens to be the status despite execution of several rural drinking water supply schemes claiming to 'cover' the remotest, driest and poorest of the villages. The previous efforts failed to deliver the goods because of either source unsustainability (lack or inadequacy of water) or lack of maintenance. The crisis continues even after laying down of the new pipeline network under the Narmada-based drinking water supply project. Tail-end villages rarely receive water, and those towards the head receive short-time supplies once in several days. Drinking water supply in rural Kutch continues thus to be widely intermittent, irregular and insufficient, ultimately hampering the 'availability' norm for enjoyment of the human right to water. Simultaneously, groundwater quality has been a long-drawn concern, but groundwater continues to be supplied widely in rural water supply schemes without any or adequate provisions for treatment, which hinders enjoyment of the human right to water from the 'safety' perspective. As narrated above, absence of a public water supply in the village, or lack of adequate or safe water in the supply system forces women and children to traverse long distances in search of water for domestic and personal use, thus thwarting the 'physical accessibility' norm for realizing the human right to water. It is also obvious that when water is fetched from a distance, its quantity would always be reduced to the bare minimum possible, thereby also hampering the 'availability' norm. All this in turn breeds 'inequality' and 'discrimination' because of women's and children's drudgery in procuring water, and also because many people end up accessing unsafe sources or procuring water in a manner that degrades the quality. Inequality is also experienced by residents of the tail-end villages when they remain left out of the network despite water supply. Absence of water or safe water may prompt people to buy tanker water or install domestic filters, but for the poorer lot, enjoyment of the human right to water through this option may remain thwarted due to the question of 'affordability'. Finally, as has been also noted in the CAG report, 2018, 'information accessibility' on water is poor, and people are often not even informed about the quality of water that they are supplied and its implications for their health and well-being. In the long run, problems with availability, physical accessibility and safety impact health and reduce physical capabilities, hampering education of children and working capacities of adults, leading to deepened poverty traps. Thus, a whole bundle of human rights connected to water gets thwarted, ultimately affecting sustainable development.

The status of realization of the human right to water in Kutch, Gujarat presented above should serve as an eye-opener. It throws up the lesson that economic prosperity and statistical achievements can in no way ensure that women, men and children living in remote villages are assured of access to adequate, safe and affordable water. Violation of the human right to water, and thereby also of the concomitant human rights like health, education, livelihoods and development can ensue despite the best-painted pictures. The situation in Kutch is actually representative of that in many other parts of rural Gujarat and also reminds one of the status of enjoyment of the right in many other parts of rural India. The situation presents many important concerns for the socio-economic welfare and sustainable development of the populations affected. It is high time that the authorities wake up to the realities of the situation, and instead of focusing merely on 'coverage', look beyond to the other necessary conditions. Only then will it be possible for rural women, men and children to sustainably enjoy their human right to water in Kutch and Gujarat in particular and in rural India in general.