Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Status of the Human Right to Water in India

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 May, 2019

The Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) as envisaged in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015) hinges on the promise of leaving no one behind in access to safe and affordable drinking water. This in turn is seen as achievable through universal realization of the human right to water recognized by the UN, which entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The norms and criteria within the UN human right to water framework, and the norms and goals set up in India within the rural and urban water supply frameworks that can help ensure universal realization of the right have been highlighted in the photo story dated 16 April 2019. Though India has formally acknowledged the human right to water resolution in the UN and played an important role in shaping the global SDGs, the status of drinking water access in the country shows that there are yet miles to go. Performance audit of the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India (2018) reveals many problems. Even after spending more than 811 billion Rupees (approx. 11.5 billion USD) over a period of 5 years (2012–2017), against the overall goal of providing by 2017 every rural person with access to 55 litres per capita per day (lpcd) of safe water for drinking, cooking and other domestic needs within the household premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not more than 100 m from the household, people residing in only 44% of rural habitations have so far been provided with such access. Further, against the goal of providing 50% of the rural population with access through piped water supply by 2017, only 18% rural population has been facilitated. The corresponding goals to be achieved by 2022 are 70 lpcd within the household premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not more than 50 m from the household and providing at least 90% of rural households with piped water supply. The audit found that poor execution of works and weak contract management resulted in works remaining incomplete, abandoned or nonoperational, while excessive extraction of ground water, inadequacy of efforts to address quality issues, lack of efforts for sustainability of water sources, and inadequate/non-maintenance of water supply schemes led to 'slipping-back' of 476,000 habitations during this period, causing violation of the residents' human right to water. The situation in urban India is equally gloomy. According to the Census of 2011, only 71% households have access to a water source within the domestic premises. With respect to particularly access to piped water supply, the figure is again 71%, with the tap water source located either within the domestic premises or outside. Against this backdrop, this photo story aims to make an in-depth exploration of the status of realization of the human right to water in India, considering both rural and urban areas, and evaluating the status vis-à-vis the different norms and criteria identified within the scope of UN framework on the right. The title photo depicts the status of human right to water in the heart of the Thar Desert in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan. Here the Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana (IGNP), that brings water from river Sutlej in Punjab, is supposed to supply drinking water through pipeline schemes in the villages. However, failure of either operationalization of this planned pipeline supply or the substandard water quality delivered by it forces rural women and girls to struggle through the scorching heat of the desert, travelling long distances for procuring potfuls of water.

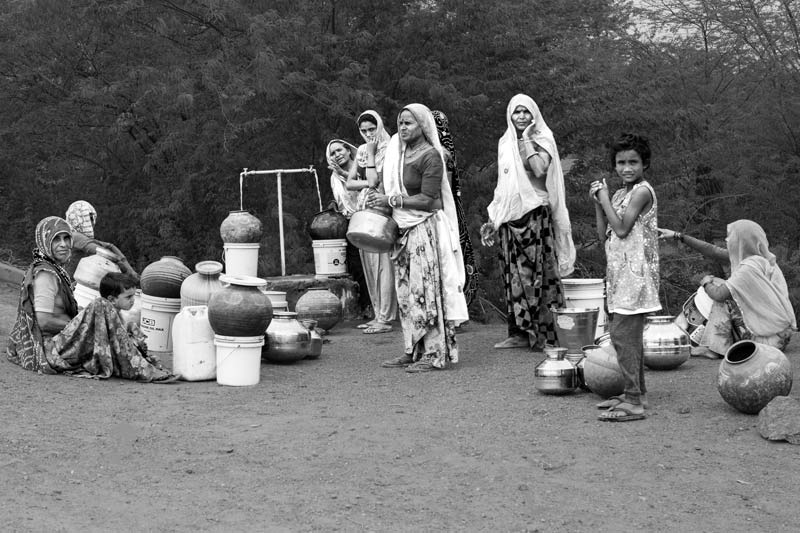

Waiting for their turn in uncertainty at a public tapstand in a village in district Tonk, Rajasthan

In line with the UN guidelines underlying SDG 6 and the human right to water framework, the national policy framework for rural water supply in India lays down that every individual is to be provided with 'adequate' safe water for drinking, cooking and other domestic needs on a sustainable basis. This water should be readily and conveniently accessible at all times and in all situations, thereby ensuring availability. 'Adequacy' is defined as 40 lpcd at a 'basic' level, 55 lpcd at an intermediary level (to be achieved by 2017), and 70 lpcd as the final goal (to be achieved by 2022). Against these goals, the CAG report of 2018 notes that more than 24% rural habitations are today devoid of even a 'coverage' at the basic service level of 40 lpcd. And in terms of the intermediate service level of 55 lpcd, more than one million rural habitations continue to remain deprived. In terms of population, against the goal of 50% coverage with provision of 55 lpcd by 2017, only about 18% has been facilitated. Further, according to audit surveys conducted by the CAG in different parts of the country, supported by the authors' own field research, availability of the source itself in no way guarantees water availability. Handpumps dry up, many piped water supply schemes remain non-functional, and where functional, in many cases the supply is quite irregular and the water pressure too low. The above photo presents evidence in this regard, where water has become available at the public tapstand after 3 days and the women were highly uncertain regarding the possibility of filling their containers, because the queue is long, pressure is low, and the water will be gone in less than an hour.

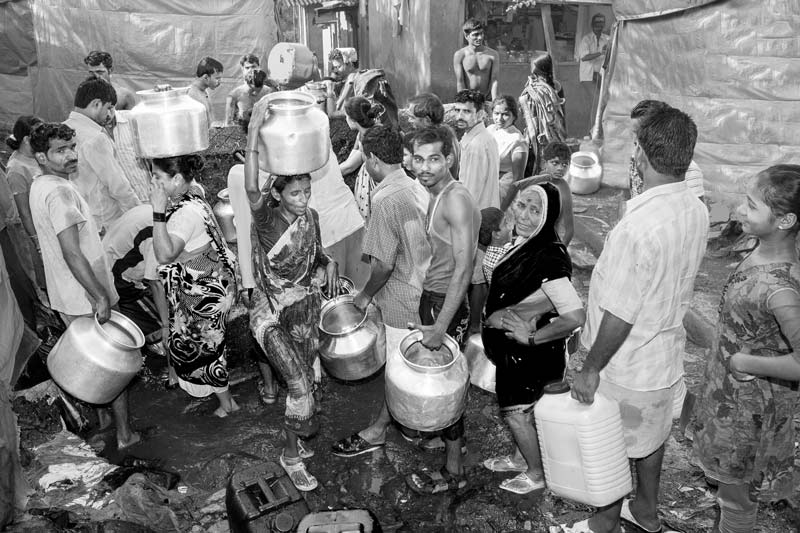

Struggling to procure a share in the scanty water supply in an urban slum in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The scenario of water availability and hence realization of the human right to water is not markedly different in urban India. Though piped water supply is the most common urban source according to Census of 2011, most cities do not provide water according to water delivery service level benchmarks (SLBs) developed by the Ministry of Urban Development in 2008. The SLBs stipulate a coverage of 100%, with water supply at 135 lpcd, and 24 hours a day. An attempt to follow the SLBs was made earlier under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) and since 2015 through Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and the Smart Cities Mission (SCM). However, studies based on data from more than 1,400 cities (2014, 2016) show that cities receive an average supply of 69 lpcd and only about 25% urban population has availability of 135 lpcd. Further, according to these reports, 60% of the urban population gets piped water for less than three hours a day, while 25% doesn't get it even for an hour per day. In terms of urban household 'coverage' with piped water supply, the average is only about 62%. The 2016 report further notes that for the 65 million urban slum dwellers, availability of sufficient and regular water supply is a perpetual challenge. An example is portrayed in the above photo from a slum in Mumbai, where a public tapstand has been provided, but does not ensure even basic minimum water availability to the users. The supply is irregular, only once a day, with no punctuality. Moreover, the duration of supply is never more than an hour, which makes the users queue up impatiently, struggling and rushing to fill their containers. The point is neither well-maintained, the floor being broken and visibly slushy.

A rural piped water supply scheme which provides water contaminated with excess fluoride and salinity in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

In accordance with the SDG 6 guidelines and the human right to water framework, the vision of the national policy framework for rural water supply in India and the NRDWP is to provide every individual with 'safe' water that meets set standards in terms of quality for drinking, cooking and other domestic needs. Despite this vision, the CAG report (2018) notes that government has paid inadequate attention to the need to ensure water quality. As many as 74,724 rural habitations have been noted as quality-affected in the report, of which 94% are affected by chemical contamination from arsenic, fluoride, iron and salinity in groundwater. Excess of fluoride and arsenic in drinking water thwart enjoyment of the human right to water and pose serious public health risks. For mitigating the problem, several solutions have been proposed, one of which is to reduce the dependence on groundwater for drinking. However, the CAG report notes that while about 11 million rural population are at risk due to fluoride in drinking water and another 17 million are exposed to arsenic in drinking water, 88% of the piped water schemes continue to be groundwater-based. High fluoride in groundwater exists in 230 districts of 20 States. The photo above shows an instance from Rajasthan where, according to government sources, all the 32 districts are fluoride-affected. Bikaner is one of the worst affected districts where both fluoride and salinity in groundwater are major concerns. However, the government continues to supply contaminated groundwater through piped water supply in the name of 'coverage' and 'improved access'.

Dental fluorosis resulting from consumption of fluoride-rich water from the piped water scheme shown before in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

According to the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), the 'acceptable' limit of fluoride in drinking water is 1.0 mg/L, while the 'permissible' limit in absence of alternate source is 1.5 mg/L. Consumption of higher levels of fluoride commonly causes dental fluorosis, skeletal fluorosis, and non-skeletal symptoms including gastro-intestinal problems and nervous system damage. Dental fluorosis causes yellow, brown or black streaks or spots on the teeth, as shown by the young boy in the photo above who lives in the same village referred earlier. In this village, constituted of about 650 households, fluoride-rich groundwater is supplied 'at home' through domestic piped water connections from four different borewells. Several children in the village are affected by dental fluorosis, and gastro-intestinal problems and joint pain are commonly reported by adults. According to one of the tubewell operators, fluoride test done in the village in June 2013 revealed a concentration of 11 mg/l, but no community water purification plants (CWPPs) nor any other mitigation options have been executed. In fact, the CAG report (2018) found that nationally only 5% of the quality affected rural habitations have been provided with CWPPs, and many water treatment units valuing more than 871 million Rupees (approx. 12 million USD) were either lying idle or became non-functional. The latter is noted as an important cause behind 'slipping back' of 31,187 rural habitations from 'fully covered' to 'quality-affected' during the period 2012-2017.

A Reverse Osmosis (RO) unit in a quality-affected urban household in East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Quality of drinking water is becoming a top concern among urban populations in India. According to a report on urban water supply in the country (2014), there exists limited monitoring and data on the quality of water supplied at the household level. According to Census of 2011, 49% of urban households have access to drinking water from treated piped water supply. The remaining 51% are not incorporated in municipal networks and instead depend upon sources that may be groundwater-based (such as handpump, tubewell or well) or river, tank, spring etc. Since groundwater in many parts of the country is microbially or chemically contaminated, quality of the water procured from these sources is unreliable. However, even for the 49% households that receive the supposedly 'treated' piped water, the nature of treatment may actually be inadequate or inappropriate to render 'safe' water to the users. For example, the traditional drinking water treatment methods adopted by municipal water supplies often aim at microbial safety but often neglect chemical contamination sourced from industrial effluents or geogenic contaminants. Besides, there may be additional contamination in the delivery network resulting from leaking pipes. The risk of quality degradation of drinking water confronts all kinds of urban dwellers – those in slums and informal colonies as well as in the better-off settled colonies, as is indicated in the photo above. Consumption of unsafe water exposes people to a variety of health risks, including diarrhea, dysentery, fluorosis, arsenicosis and even cancer. For securing health, urbanites are forced to spend substantially extra for measures such as water filters or bottled water, which may compromise their other capabilities and living circumstances.

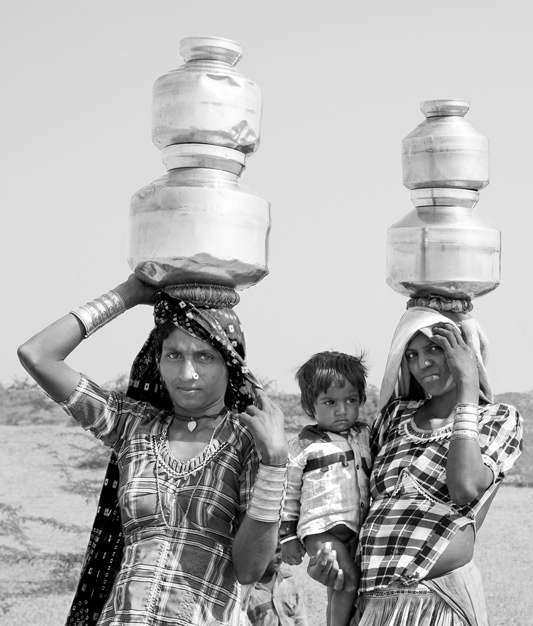

Fetching loads of drinking water from a distant source in Kutch district, Gujarat

Physical accessibility to sufficient and safe water is the third norm under the UN human right to water framework. Towards this end, the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply in India emphasizes on piped water supply and had the goal of placement of the source within either domestic premises or at a horizontal or vertical distance of not more than 100 m by 2017. Further, a goal of providing at least 35% of rural households with domestic piped water connections by 2017 was set-up. However, as per the findings of the CAG report of 2018, only 18% of the rural households had been provided with piped household connections. Besides, 476,000 rural habitations that were previously 'fully covered' by piped water, handpump or other sources are noted to have "slipped back" during 2012-2017 due to non-functional or quality-affected water sources, forcing women and children (especially girls), to procure drinking water from distant sources. A longer distance implies longer time per trip, which in turn, reduces the number of trips undertaken, but increases the load per trip, as is evident from the photo above.

Procuring water from a distant source in Mumbai, Maharashtra

In urban India, physical accessibility of water is a huge problem. According to Census of 2011, 29% households do not have access to water within the premises, and 8% need to fetch water from a distance of more than 100 m. In terms of piped water supply, the access within the premises exists with only 54% urban households. Even many of those with piped water supply at home may still suffer due to lack of access to regular, sufficient and safe water. Regarding the slum population which numbers more than 65 million, a study from 2014 notes that residents of more than 28% households must walk 100 metres or more to collect water because of lack of piped water or other alternate water sources nearby. The above photo is a case in support from Mumbai where lack of a water source within the slum locality forces these women to walk every day to a distant group connection to buy water, transporting it manually in barrels. Even though 570 water supply projects were sanctioned under the JNNURM (2008-2012) for improved urban infrastructure in 65 cities, the status of urban water access in India continues to remain dismal. A CAG audit report of 2012 which examined 37 of these projects under JNNURM revealed that only three had been completed. No figures have yet been made available regarding the progress under the new AMRUT and Smart Cities Mission.

A local vendor distributing treated packaged water for a price from a Reverse-Osmosis (RO) plant in Bhojpur district, Bihar

According to the fourth norm under the human right to water framework of the UN - which is supported by the legal and developmental frameworks in India - water, and water facilities and services should be affordable for all. This means that any direct and indirect costs and charges associated with securing water must not limit people's capacity to buy other goods and services essential for life. Due to inadequacy of water and degraded water quality primarily resulting from inefficiently implemented rural water supply programs (as noted earlier), rural populations in many pockets of India are prone to spend extra for securing access to adequate and safe water. This may even force them to compromise with other necessary domestic expenditures such as for food, housing, health and education. Buying packaged drinking water, depicted in the photo above, is one of the ways to secure access to safe water, because it often assumed that packaged drinking water is treated and hence safe to consume. Irrespective of the extent of 'safety' offered by the packaged water – an issue raised in some studies, packaged drinking water costs money, and therefore long-term dependence on water purchase may seriously thwart the affordability of other necessities of life for the rural poor. Unfortunately, there is lack of data on the extent to which rural populations in the country are paying for procuring safe and sufficient water for personal and domestic use.

A tubewell which produces unsafe water for urban supply in a suburb of Kolar city, Karnataka

In many urban areas, availability as well as quality of water for personal and domestic use is a significant challenge. As noted earlier, piped water coverage may be lacking (as in slums), and even if present, the water supply may be inadequate and irregular. Further, lack of emphasis on monitoring the quality of the water supplied can lead to additional burdens for the users. The above photo depicts such a situation where a newly planned colony is supplied water from a tubewell but the water is saline, which makes it unfit for consumption. Further, it contains fluoride above the permissible limit of 1.5 mg/l, putting the health of the residents in jeopardy. Consequently, while the water supplied is used for washing, bathing, cleaning and other non-consumptive uses, for drinking purposes the residents are forced to purchase water, bringing additional financial burden. There exist several such urban areas that are officially recorded as 'covered', but the people are denied the opportunity to enjoy their human right to water due to problems with economic accessibility.

Buying potable water from a tanker in a salinity and fluoride-affected suburb of Kolar city, Karnataka

When confronted with water quality problems, water shortage or absence of piped water networks in urban areas, people are forced to buy water to meet their daily needs. It is already globally recognized that residents of urban slums and other unserved urban areas often end up paying double or even higher prices for water compared to those covered with adequate and safe water. In the long run, this may bring up the problem of affordability, since the people might not have enough to pay for water and instead compromise with other necessities such as food and education. The above photo shows the situation in an urban settlement served by the contaminated tubewell in Kolar city shown earlier, where people buy drinking water from private tankers on a daily basis. However, even after paying substantial sums of money for procuring sweet and safe water, the people are not satisfied about the quality of the water. They say that sometimes the tanker suppliers mix saline groundwater with 'sweet' water which makes it sweeter than the water from the tubewell but does not guarantee quality in terms of taste and protection from fluoride. This perception of the residents holds true, because there exists no system for water quality monitoring for the tanker water suppliers. However, in the absence of a better alternative, the residents are forced to buy the tanker water.

A men-only meeting for discussing water issues in a village in Mansa district, Punjab

The fifth norm for ensuring universal realization of the human right to water is 'non-discrimination', which requires governments to give special attention to those individuals and groups who have traditionally faced difficulties in exercising this right. Women are recognized as a significant group in this category, and governments are obliged to ensure their inclusion in decision-making processes concerning water. The government of India's Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply includes the relevant provision in this direction, but women's participation in decision-making in rural water supply sector continues to be low, thus depriving them the opportunity of expressing their views and influencing the decisions at the local scale. The above photo shows a meeting of villagers gathered to discuss about the water challenges in the village, but women are conspicuous by their absence, though they are the ones primarily responsible for procuring domestic water.

In the absence of water sources close to home, rural women bearing the disproportionate burden of carrying heavy loads of water from a distant source in Kutch district, Gujarat

The human right to water norms about non-discrimination stipulate that the disproportionate burden that women bear in the collection of water should be alleviated. However, inadequate efforts on part of the government in promoting women's participation in decision-making on water and ineffective implementation of rural water supply programs limit their sustainable access to adequate and safe water at or close to home. This continues to put disproportionate burden on them as domestic water managers, forcing them to traverse long distances in search of water, transporting heavy loads of water manually. If the water source is distant, then women may prefer to carry multiple containers in one trip, as is shown in the photo above. This is tiring as well as brings health risk as transport of heavy loads of water on the head, shoulders or waist can cause neck and back pain as well as spinal injury. In case of pregnancy, as true in the above photo, this may result in additional complications.

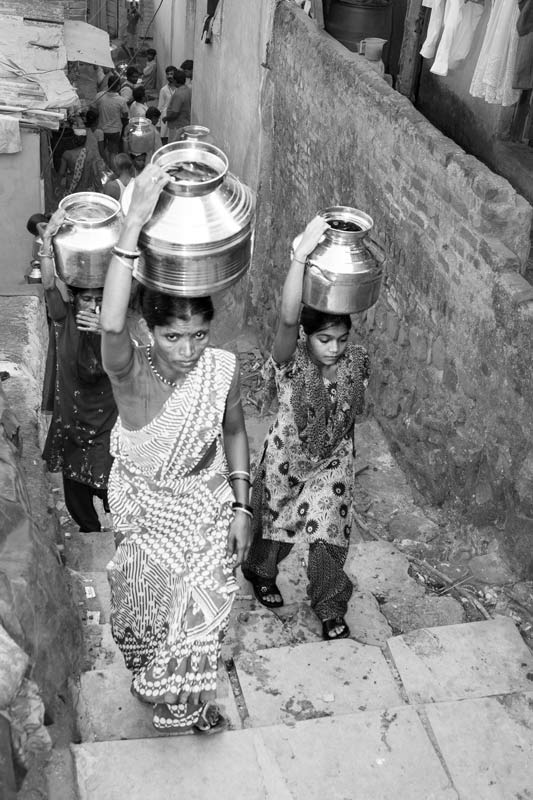

Urban women and girls fetching water from a distance more than 100 m, carrying headloads over steep stairs in Mumbai, Maharashtra

According to the Census of 2011, 29% urban households lack a water source at home. In many of these households, it is the women and girls who undertake the arduous task of manually transporting water for domestic and personal uses from public tapstands, tankers or other communally available sources. The distance may vary between a few to several hundred meters and the terrain may be flat or undulating. In Mumbai, several slums and informal settlements are located across hilly terrains where water needs to be hauled over steep staircases from public points that are located down the hill, as shown in the photo above. Sometimes, the supply timings are extremely odd, and water needs to be transported in the dark of the night. In these circumstances, the disproportionate burden on urban women and girls in the collection of water gets deepened. Carrying heavy headloads on a regular basis is tiring, poses risks of cervical and spinal injury, and takes a heavy toll on their productive or educational time. Further, traversing long distances alone in the night may pose security concerns.

Defunct handpump within school premises in Bangalore Rural District, Karnataka

According to the norms regarding 'non-discrimination', governments are obliged to give special attention to children as a group that has traditionally faced difficulties in exercising the human right to water. This has led to the need to ensure provision of adequate safe water facilities within the premises of all government schools and child-care ICDS centres, as is laid down in the Strategic Plan (2011-2022) on rural water supply in India. For quality-affected areas, Jalmani Scheme has been specially launched with the aim to provide safe water to children studying in rural schools through installation of water purification systems. For private schools too, provisions of the Right to Education Act are to be followed. However, safe water sources in many schools continue to be missing and, where present, these fail to be properly maintained, an instance of which is shown in the photo above. According to the CAG report of 2018, 150,000 schools and child-care ICDS centres lacked drinking water facilities. Further, a test check of records by the CAG regarding the Jalmani Scheme showed that out of the 3,302 water purification systems in six States, 2,439 systems valued at 42.4 million Rupees (more than 0.6 million USD) were either not installed or not functional. All these figures are indicative of the extent to which children in governmental educational institutions are deprived of the opportunity to enjoy their human right to water, while parallel figures for the private educational institutions are not available.

School girls carrying home water from a village handpump in Morena district, Madhya Pradesh

As noted above, the norms regarding 'non-discrimination' in the human right to water framework consider children as a special group with respect to enjoyment of the right. Governments are thus obliged to ensure that children are not prevented from enjoying their human rights due to the lack of adequate water in households or through the burden of collecting water. However, in many of the uncovered 400,729 habitations in rural India where access to even 40 lpcd is lacking, and the nearly 111 million households which lack a water source within the domestic premises, children, especially girls, often assist in domestic water procurement, manually transporting heavy loads of water, as shown in the photo above. While a lack of safe and adequate water at home directly puts health and wellbeing of the children at risk, a more pertinent risk arises for these children when they assist their mothers and family in water collection by travelling to distant sources, queuing up at public water points, carrying multiple loads back home, sometimes also undertaking multiple trips during the day. Carrying heavy loads of water poses risks of neck and spinal injury and retarded growth and hampers their education and other developmental activities. Sometimes they must walk through deep forests or secluded areas, further raising security concerns.

A slum-dwelling girl assisting her family with domestic water procurement in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Many children living in urban areas share a fate similar to their rural counterparts. In the unserved urban settlements and in the urban households that a lack water source, children undoubtedly assist their parents in procuring water, with girls playing a more active role from early ages. According to Census of 2011, there exist about 23 million urban households that lack a water source within the domestic premises. Of these, about 17 million households procure water from a source located within 100 m while the remaining 6 million depend upon sources further away. The girl shown in the photo above lives in a slum that lacks municipal coverage and hence is forced to travel everyday to a distant water point.

Collecting scanty but unclean drinking water from an unprotected source in Mon district, Nagaland

According to the UN human right to water framework, rural areas have should have access to properly maintained water facilities. The Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply and the NRDWP aimed to ensure that all rural populations have access to adequate, safe and affordable water for domestic and personal use at 55 lpcd by 2017. However, as noted by the CAG report of 2018, the target is far from being achieved, and more than 400,000 rural habitations are devoid of even a 'coverage' at the basic service level of 40 lpcd. Moreover, negligence of components such as preparation of sustainability plans, construction of sustainability structures and involvement of local communities has led rural communities lack sustainable access to adequate and safe water. For example, in the village communities located on hill tops in Nagaland, seasonality of water sources is a pertinent problem, which has deepened the hardships of local communities in accessing water round-the-year. As the dry season advances, the spring-based water sources higher in the hills dry up and people are forced to search for water down the slopes where natural seepage collects in shallow depressions. Such water is scanty and visibly unclean, but in the absence of any alternate water source, many hill communities are forced to collect and consume such unsafe water, as evident in the photo above.

Slum residents using water for various domestic and personal uses from a pipeline leakage in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The UN human right to water framework obliges governments to ensure that deprived urban areas have access to properly maintained water facilities, and that no household should be denied the right to water on the grounds of their housing or land status. Towards this end, the SLBs stipulate a coverage of 100%, with round-the-clock water supply at 135 lpcd. Despite these guidelines, many urban households continue to lack access to a proper water source. Those living in slums are often deprived of access to piped water connections on grounds of lack of legal status of their dwellings. In the absence of proper water sources, in many cases, residents of slums and informal urban settlements are forced to make use of leakages in water pipelines that pass close to their settlements, using the water for all purposes, such as for collecting drinking water, and for washing and bathing on site. The inaccessibility of such sources may raise questions of physical safety (as for the woman sitting atop the pipe), and also multifarious use by all may raise a concern for gender sensitivity, as is evident in the photo above.

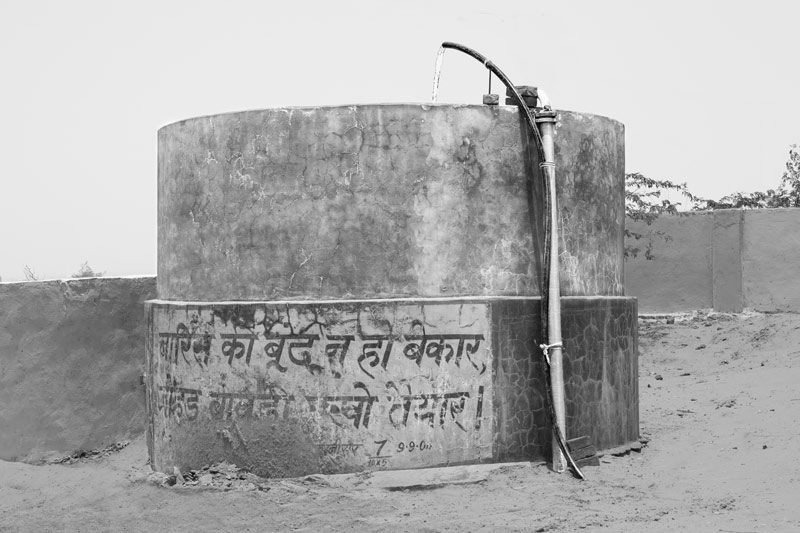

An unmaintained and illegible water IEC message for community sensitization in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

Information accessibility is another important criterion for ensuring the human right to water, which requires that individuals and groups should be provided with full and equal access to information concerning water, water services and the environment, held by public authorities or third parties. The Strategic Plan (2011-2022) for rural water supply recognizes this criterion and requires that States should design and implement appropriate behavior change communication. However, the CAG report of 2018 has noted that action plans for Information, Education and Communication (IEC) have not been adequately drawn, leading to low thrust on IEC with regard to aspects such as water quality concerns, water conservation, community participation, and water sustainability. Research by the authors further shows that sometimes IEC messages are written at inappropriate places, do not exactly address the IEC needs of the target group, and worst, there is much negligence in ensuring upkeep of the messages that have been already produced for mass awareness. One such example of negligence is portrayed in the photo above. As a result of lack of proper IEC, awareness and motivation in local communities remains low which in turn affects planning, implementation and monitoring of water supply programs.

This photo story has portrayed the status of realization of the human right to water in rural and urban India. Several hundreds of billions of Rupees have been spent over the decades for augmenting rural and urban water supply in the country and undoubtedly there has been progress on this front. However, the current progress is not enough for ensuring that no one is left behind in access to adequate, safe and affordable water. This would require fulfilment of the goal of 100% rural water provision at 70 lpcd and urban water provision at 135 lpcd, the water being readily and conveniently accessible at all times and in all situations. At present, there remain significant deficiencies on both quantitative and qualitative fronts in this regard. In rural areas, piped networks often remain devoid of water, the supply is characterized by irregularity, low pressure and inadequate and inappropriate timings. Many unserved urban settlements continue being deprived of water due to exclusion from piped supply networks and any alternate sources provided are often inadequate. Moreover, access to water source within the domestic premises continues to remain limited, causing significant hardships. Similarly, the goal of 'safe' water provision through piped networks and other means in both rural and urban areas is lagging. In fact, monitoring of water quality is poor, and many rural and urban communities continue being supplied with unsafe, untreated or inadequately treated water through supposedly 'improved sources', namely piped water networks and handpumps. Consumption of unsafe water as well as inaccessibility and inadequacy of water breeds ill-health and disease of various kinds, in turn causing financial burdens, reducing work efficiency, and thwarting children's education and development. Affordability is also emerging as an important issue because people are forced to spend much on water due to lack of adequacy as well as degraded quality of the water supplied. Extra expenditure on water forces domestic cuts on other necessities, thus lowering the quality of life in general. The principle of 'non-discrimination' is violated along several different axes. For example, women and children's drudgery is not reduced, women's participation remains conspicuous by its absence, people in unserved rural and urban settlements remain neglected, and schools and educational institutions continue to lack access to safe and adequate water. Also to be noted is the fact that while a clearer assessment of the status of enjoyment of the human right to water is available for rural India, a similar picture of the current urban scenario is missing. The achievements of the latest interventions AMRUT and Smart Cities Mission are not reported even after more than four years of implementation.

Some of the observations made by the CAG report of 2018 regarding the NRDWP hold good also for the urban water supply initiatives. Similar observations have emerged from the authors' own research across the length and breadth of the country. Among others, these include lack of proper planning, inefficient and ineffective execution of works that result in undue delays and expenditure that fail to yield expected results, inadequate efforts regarding sustainability and maintenance of water supply schemes, lack of community participation, and poor efforts at community sensitization and behavior change through IEC. In this light, it is evident that despite the progress made with regard to water provision for rural and urban communities of India, holistic realization of the human right to water still remains far behind. Much therefore remains to be done if the sustainable development goal of leaving no one behind in access to adequate, safe and affordable water for personal and domestic use is to be achieved. There is need to look into the current gaps and weaknesses, redesign and refine the current efforts and strive to achieve effective implementation of rural and urban water supply programs. Otherwise, women, men and children's human right to water will continue to remain unrealized, in turn thwarting their other human rights such as that to health, education, sustainable livelihoods, and over-all development.