Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Status of the Human Right to Water in Mumbai

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

29 July, 2019

Under the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015), the government is obliged to ensure that no one is left behind in access to safe and affordable drinking water which, in turn, requires universal realization of the human right to water. This right entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The norms and goals set up in India within the scope of the UN’s human right to water framework were presented in the story dated 16 April 2019, and in-depth analysis of the status of realization of the right in India in general and Delhi in particular were presented in photo stories dated 15 May and 15 June 2019 respectively. This photo story reviews the status of the human right to water in Mumbai - the financial and commercial capital of India and the capital of the state of Maharashtra, being the second wealthiest Indian city based on GDP. However, despite its wealth, access to safe and affordable drinking water for all in Mumbai presents several challenges. As per the Census of 2011, it is the country’s largest and world's eighth largest city by population, being home to more than 12 million. According to a city assessment conducted by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and Safe Water Network in 2016, the rich and poor, planned and unplanned settlements alike suffer from inadequate and unreliable water supply. Mumbai comprises the Mumbai City and Mumbai Suburban districts, together referred to as ‘Greater Mumbai’ where the production and supply of drinking water is the responsibility of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM). Against the service level benchmark (SLB) of 135 million liters per day (MLD) set by the Government of India, MCGM is reported to supply only about 90 liters per capita per day (lpcd) in the planned colonies. In the unplanned settlements – the slums - where about 42% of the city’s population resides in more than a million households, the situation is worse. Here, the water access is estimated to be around only 25 litres per day per household (not person) or none at all, since MCGM supplies water only in the notified slums. This excludes about half of the slum population who are left to fend for themselves, paying up several times more for procuring scanty water of unreliable quality from distant sources. Additionally, according to the Census of 2011, there are more than 15,000 houseless households, living on roadside, pavements, in hume pipes, under fly‐overs and staircases, in places of worship, railway platforms, or out in the open, who lack any regular access to water for fulfilling basic human needs. Moreover, groundwater as well as surface water bodies are increasingly rendered unfit for drinking because of pollution from untreated sewage and industrial effluents. Leakage from sewage lines also contaminates the treated drinking water carried in the city’s aging pipelines. Thus, the norms of ‘availability’, ‘safety’, ‘physical accessibility’, ‘affordability’ and ‘non-discrimination’ necessary for realizing the human right to water all remain seriously thwarted. The final norm regarding human right to water is ‘information accessibility’, which too is weak. Against this backdrop, this story will make an in-depth exploration of the realities regarding enjoyment of the human right to water in Mumbai. The title photo portrays how precious water is for the residents of Dharavi – considered to be one of world's largest and most densely populated slums - with a population of about 700,000 living in an area of just about 2.1 square kilometers.

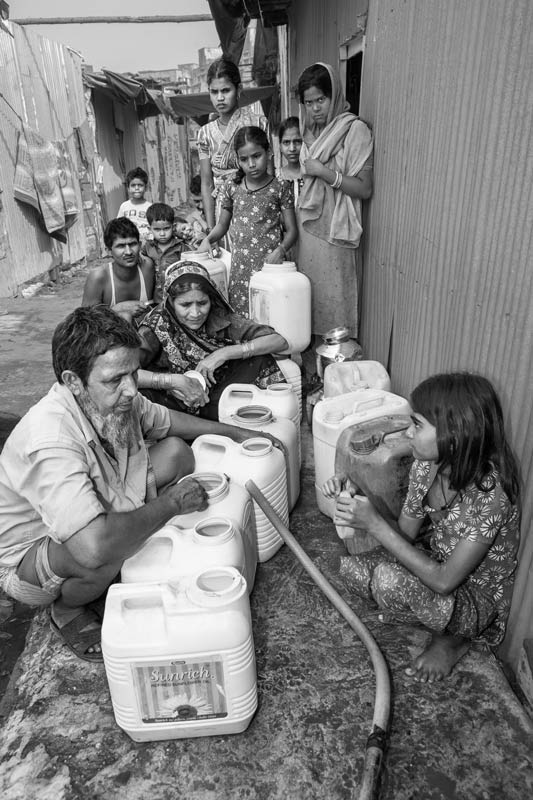

People in a slum waiting in uncertainty for water to arrive

Mumbai is a city of striking contrasts, with elite neighborhoods surrounded by large pockets of informal settlements or slums. According to media reporting from 2018, there exists a general shortfall of 400 MLD in water supply to the city, but even this inadequate water has a skewed distribution. While the upper-middle class residing in posh localities receive lion’s share up to 300-400 lpcd, the slum-dwellers fail to receive even 40 lpcd considered to be the basic minimum. According to some estimates, Mumbai has the largest slum population of any city in the world, and the Census of 2011 records a figure of more than 5.2 million slum dwellers. Further, the MCGM is obliged to provide water for personal and domestic use in only the ‘notified’ slums which constitute just about half of the city’s slums. This implies great inequity in water access in general. Further, even in the notified slums, the water availability is highly inadequate while challenges in the non-notified slums is even worse. The photo above depicts an example where in a notified slum, the supply time is uncertain and short, and the quality is not perceived as ‘good’ by the users. Thus, in the slums, there exist serious challenges to exercise of ‘availability’, ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘quality’ norms of the human right to water.

Impatiently waiting for their turn at a group connection in a notified slum

A notified slum in Mumbai is one where households have been settled on state or city government-owned land prior to the year 2000. In a notified slum, the residents are eligible to apply for water supply in groups of five to 15 households through the ‘Stand Post Water Connection’ scheme, more commonly called ‘group water connection scheme’. These eligible households form a ‘Tap Committee’ and apply for a metered group water connection. The MCGM provides water supply from the nearest Mains to an agreed upon common location in the slum cluster. Thereafter, extension of the feeder within the cluster as well as its management is the Committee's responsibility. The users pay a subsidized water tariff and more than 162,000 such metered stand post connections are estimated to be in existence. However, the areas which are covered under group water connections often receive intermittent supply of water, with short durations and at low pressure. Women, who are primarily responsible for procuring domestic water, have to spend long hours first waiting for water to arrive, and later to fill their containers with the scanty water coming at low pressure, as shown in the photo above. At the end, some women may even have to return empty-handed. These situations illustrate how the ‘availability’ norm necessary for enjoyment of the human right to water stands thwarted in Mumbai, since neither is the water supplied sufficient, nor is it continuous.

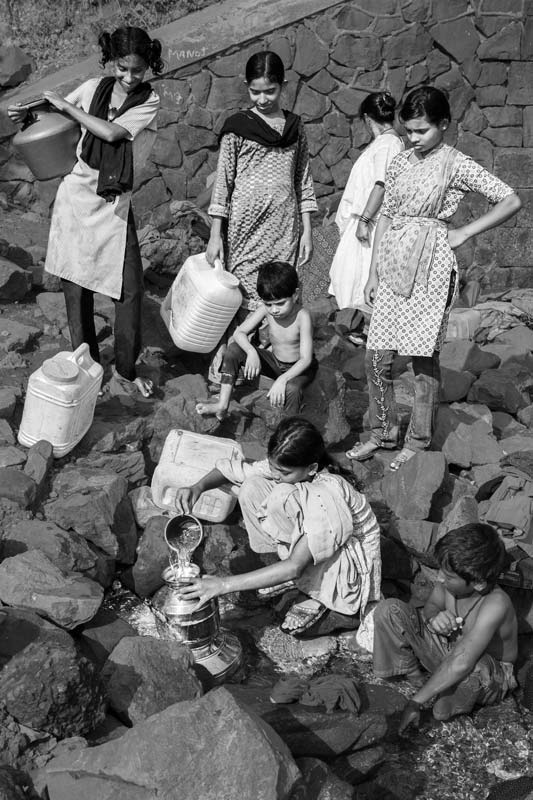

Drudgery of women and girls in an informal settlement located on hills

Mumbai has an undulating terrain, with three hill ranges within the city limits. Many of the slums are located in the hilly terrain, which adds to the water woes. The gravity-based system of water distribution provides water only up to certain height along the road after which it requires to be manually hauled up to dwellings located higher up. This causes great hardship especially for women and children, who are the ones primarily responsible for domestic water management. The photo above depicts one such scene with women and girls hauling up heavy pots of water over a steep staircase. This is a regular everyday activity in their lives – taking a heavy toll on their health and wellbeing. Not only does carrying heavy water loads up the stairs lead to risk of neck and spinal injuries and pain, but rapid trips over the steep stairs increase the risk of slipping and falling, resulting in fractures and bone injuries. Such a situation poses a serious challenge to exercise of the ‘physical accessibility’ norm of the human right to water.

Children hauling loads of water compromising their valuable study or play time

In the notified slums of Mumbai, water is supplied at different hours of the day, with the exact time of arrival of water often uncertain and the duration of supply short. Under such circumstances, for maximizing the collection of water at household level, children’s services are often sought, which may lead to missing of school, or valuable study hours at home, or even compromising play time essential for their healthy growth and development. Moreover, carrying heavy loads of water can lead to spinal, neck and muscle injuries, as well as cause stunted growth in young children. In the notified slum shown in the photo above, water comes in the afternoon for approximately 45 - 60 minutes, and the pressure is quite low. Moreover, the time of water supply coincides with the working time of adults. Therefore, in order to ensure water collection for fulfilling the domestic water needs, several children participate in the activity, carrying heavy loads of water, putting their health, education and development into jeopardy. Children living in non-notified slums share similar or even worse fate. Such a situation with children violates the ‘non-discrimination’ norm for enjoyment of the human right to water.

Making multiple trips over stairs with headloads of water

The water received in the slums of Mumbai through pipelines, whether legalized or illegal, is available for short durations. This forces women, children and even men to maximize the volume of water collected at household level, making quick multiple trips between the supply point and the house. While this exercise is difficult and exhausting, such multiple trips over stairs in the hill settlements as shown in the photo above also leads to accidents and injuries, as reported by people in a number of such settlements during the field work conducted by the authors. The situation is violative of the norms of ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘availability’ connected with human right to water.

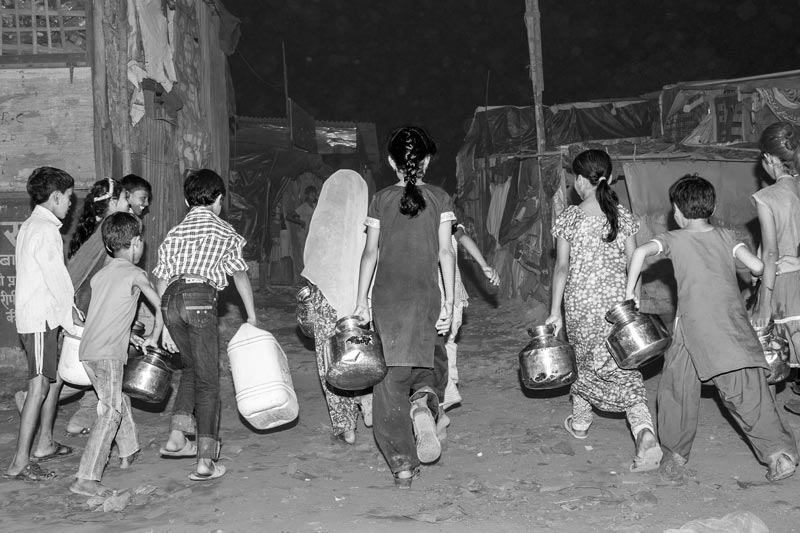

Rushing to fetch water at 9.30 in the night

In some informal settlements, water arrives in the pipelines late in the night. Irrespective of the hour, children often rush to help their families fetch water. In the slum shown in the above photo, the water situation is very critical. There exists only one illegal connection from where only those families that have paid for the cost of the connection can take water. Water arrives in the night after 9 o’clock for only 30 to 45 minutes at a low pressure. Children participate actively in water collection from the supply point, compromising their critical study or sleep time. For the remaining families in this slum, children and others have to walk about 1.5 to 2 kms to a nearby settlement to procure water. Such a situation compromises with the ‘availability’, ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘non-discrimination’ norms associated with the human right to water.

Rejoicing on arrival of water at a group connection though late in the night

At a group connection, there exist many water collection points along one single pipeline, and water is taken by inserting plastic pipes into them, as is being done in the photo above. Every eligible user household is allotted one specific point along the pipeline for water collection. In some slum settlements, a group connection, originally designed for only 5-15 households, is illegally scaled up to serve as many as 70-80 households. This is done to facilitate water access for ineligible households (mostly tenants), late entrants or those who lack necessary documents for application. As a consequence, from a common feeder point, multiple points are provided along one or more lanes, which leads to extreme lowering of pressure during the short supply time, which often ranges up to a maximum of one hour, only once a day. Under such circumstances, irrespective of the time of supply, procuring water must be a family effort. The above photo depicts the scene as late as around 10 o’clock in the night when every family member, regardless of age and gender, is participating to fill as much water as possible. To get maximum water and to ease the entire process, the tactic of relay is adopted by many families – passing the water load from one to the next. However, despite all efforts, collecting adequate water for the family remains an unfulfilled mission for many. The rush and haste at group connections reflects how the human right to water norms of ‘availability’, ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘non-discrimination’ remain unmet.

Rush at a group connection to collect water in the night

The group connections are often provided along the roads and supply hours can be rather odd. The photo shown above depicts the scene of water collection as late as 10 pm, when hundreds of people have crowded the road to collect the scanty water provided. After a long day of hard work, engaging in water collection in the night is extremely tiring, particularly in this settlement, where water containers are to be carried up the hills. Further, it exposes people to risks of injury, since water needs to be carried hurriedly through steep narrow stairs in the dark of the night. Consequently, accidents are common here, as reported by the people to the authors during their field visit, including death of a child and several casualties with broken hands and legs. Such a situation is a clear violation of the norms of ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘availability’ necessary for enjoyment of the human right to water.

Boatmen quarrelling for their turn at a public tap at Gateway of India

Mumbai is a coastal city and boating is an important tourist activity. The monumental Gateway of India is the most important boat terminal of the city, with more than 90 boats in service. However, water is an essential resource for personal use by the boatmen, including drinking, bathing, washing and cooking, and also for providing to the passengers. For fulfilling the water needs of the boatmen, a few taps have been installed by MCGM at the terminal, but the supply is only for a maximum of 1.5 hours a day. With at least a thousand buckets to fill, the water supplied is inadequate, always leading to conflict and violence among boatmen, as seen in the photo above. In fact, many of them even fall in the sea while fighting, since the water supply point is located next to the sea. The water provision for Mumbai’s boatmen is thus violative of the ‘availability’ norm for enjoyment of the human right to water.

Privatization of a public water tank in a slum being contested by women

Besides the limitations posed by the municipal water supply in terms of quantity and quality which restrict enjoyment of the human right to water by the slum dwellers as illustrated before, privatization of public water supply is also a serious problem. The photo above depicts the situation in a slum where piped water connection is missing but arrangement for public water supply has been made by installing large-sized plastic water tanks that are regularly filled by water tankers. However, despite this arrangement, the residents lack access to water because these tanks are controlled by local strongmen, who either sell the water at a good price, or keep it for their personal use only. Under such circumstances, local women are the worst sufferers since they are unable to procure water for domestic and personal use. The photo above shows members of the local Mahila Mandal (Women’s Association) protesting against the illegal sale of public water and monopoly exercised by the strongmen. Privatization of public water resources in the above context thwarts the norms of ‘non-discrimination’, ‘physical accessibility’ as well as ‘availability’ of water for the poor slum dwellers.

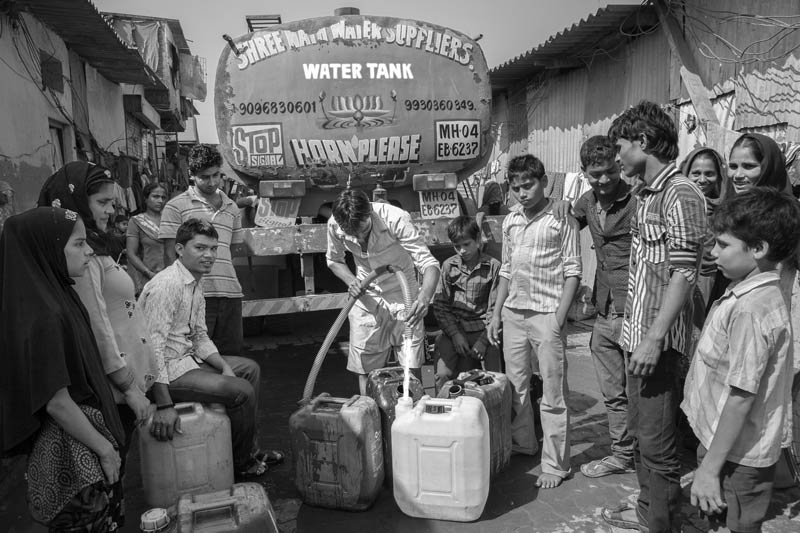

Buying tanker water in the absence of public supply

Residents of non-notified slums that lack municipal water supply face even greater challenges in fulfilling their water needs. They are forced to procure water from alternatives that may be more time-consuming, difficult or expensive. In some non-notified slums, the residents collectively buy water from private tankers, sharing the cost among them, as depicted in the photo above. This exercise may turn out to be unaffordable for some, forcing them to compromise with other necessities of life such as food, health and schooling of children. The question of affordability also sometimes arises for residents of notified slums, especially during the dry season when water cuts are imposed on the already scanty water supply, forcing them to purchase water from tankers or other sources. It has been generally observed that residents of informal settlements end up paying several times more for water compared to those living in planned colonies with municipal water supply. This leads to violation of the norm of ‘affordability’ for ensuring enjoyment of the human right to water. Also, it may be difficult to ensure the ‘quality’ of the water procured, thereby also thwarting this human right to water norm.

In the absence of public water supply, transporting water purchased from a distant group connection

Another alternative exercised by the residents of non-notified slums is buying water from distant group connections. As reported in a study made in 2014, in some slum clusters, local strongmen gain monopolistic control over ordinary group water connections and operate as water vendors. Such water vendors sell water via flexible PVC pipes in zones controlled by them or to the residents from other slums in need, as found by the authors during their field study. The above photo shows a woman returning home with loads of water purchased from a distant group connection, since their house lacks municipal water supply. In such a context, the human right to water norms of ‘affordability’, ‘physical accessibility’ as well as ‘availability’ are thwarted.

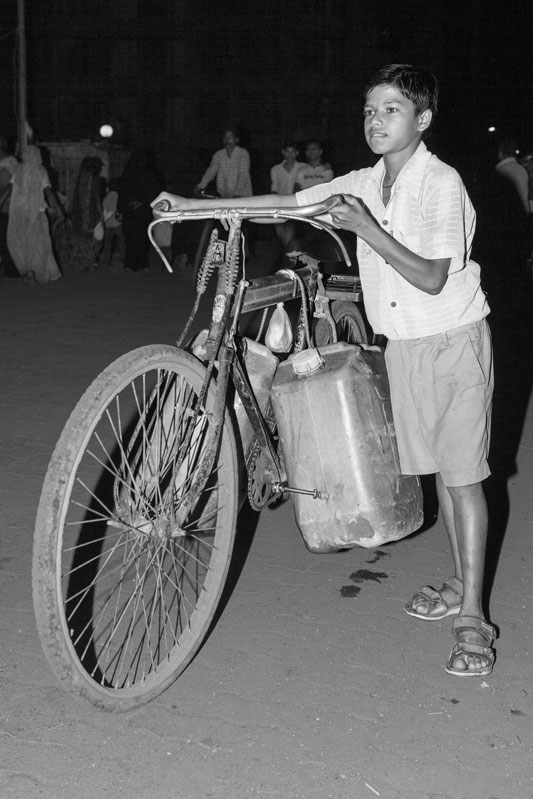

Bringing water from a distant group connection in the night

The boy depicted in the above photo resides in a slum settlement where the group connection has been monopolized by an influential lady who allows only some households to procure water from the connection. Those excluded are forced to walk about 1.5 to 2 kms to another settlement to fetch water, where the supply hour is late in the night and water needs to be purchased. This causes unnecessary hardships to the residents – physical and financial - despite the presence of a group connection in the vicinity of their houses. In such a context, the norms of ‘physical accessibility’, ‘affordability’ and ‘availability’ necessary for enjoying the human right to water are thwarted.

Collecting water from a leakage

Those who are still unable to access adequate water for personal and domestic use under the arrangements illustrated above, have to depend upon pipeline leakages or other odd sources. The photo above depicts water collection from a leaking pipeline. As evident, the leakage is meagre and therefore the task is tedious and time-consuming. Consequently, while adults may need to engage in livelihood activities, children have to bear the burden, leading to their absence at school. In this context the human right to water norms primarily thwarted include ‘physical accessibility’, ‘availability’ and ‘non-discrimination’.

A pipeline leakage serving as a water source for neighboring unserved slums

A number of slums are located close to the city’s supply Mains that carry water to the planned colonies or the industrial hubs. However, the pipeline network in Mumbai is old and aging, leading to significant leakage which is estimated to be as high as 20%. This implies a water loss of about 700 MLD for the city, but slum inhabitants who lack regular access to adequate water, end up using the leakages as water sources. The leaking pipeline Mains shown in the photo above officially serves an industry but has become an unofficial water supplier to a nearby slum. However, this water source comes with a price for the dependent public. There is generally rush and struggle to climb up to the top to insert pipes for withdrawing water. Since the water Mains has a large diameter, its height is substantial, and the surface becomes slippery with water. Under such circumstances, people have reportedly slipped and fallen, getting serious injuries in an attempt to procure water. Moreover, those that come to carry out their daily chores such as washing at the source also face the risk of falling and hurting themselves since the ground is uneven. On the whole, location of the source outside the settlement and such difficulties in accessing the water at the source raises issues of ‘physical accessibility’ in enjoying the human right to water.

Using a pipeline leakage as a public bathroom near an unserved slum

As stated before, pipeline leakages near slum settlements are often used as important public water sources. Apart from collecting water for drinking, cooking and other domestic uses, slum dwellers, especially men and boys, also use these as public bathrooms, as shown in the photo above. While a good shower may not be possible with the scanty water collected from their group water connection or purchased from distant sources, this kind of use raises an important concern for privacy, especially for those that bathe. Moreover, the surroundings here are also muddy and unclean, which makes the venture unsafe due to risk of slipping and falling. The situation also raises a question of gender equity since it is not at all appropriate for women to use the place for personal hygiene, who thus remain deprived of access to adequate water for the purpose. Thus, ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘non-discrimination’ as human right to water norms remain unmet in this context.

Meticulously filling a bucket from a leakage just above a wastewater drain

Sometimes in the absence of adequate and regular water supply, slum dwellers depend upon innovative water alternatives such as the one depicted in the photo above. Here, water is fetched from a discharge located just above a big wastewater drain that carries untreated sewage from the colony. Nobody knows the source of the water from the discharge, but the users consider it to be safe for all domestic uses except drinking and cooking. It appears that runoff from the local drain mixed with water leaked from the pipelines and handpumps in the slum percolates through soil and emerges later as a discharge falling into the wastewater drain. This situation is a depiction of the extreme of lack of water access in the slums of Mumbai, where people are ready to collect and use water from any source that they can lay their hands upon. In this context, the human right to water norms seriously thwarted are ‘availability’, ‘quality’ and ‘non-discrimination’.

Drawing of water from a nearly dried and filthy hole near a Pardhi locality

The Pardhi constitute one of most marginalized communities in Mumbai. The situation of access to water in one Pardhi community living in a non-notified slum is represented in the above photo. This community lives under conditions of abject poverty and lack municipal access to water for fulfilling basic domestic and personal needs. There is absence of group connection in the settlement due to lack of proof of residence before the cut-off date of 2000. Pardhi women are thus forced to either take water from a nearly dried up and filthy water hole shown above, the water being used for almost all domestic and personal uses. However, this water is inadequate as little water collects in the hole through seepage from underground sources or from the water mains that passes nearby. The water is so little that it finishes in just one to two small buckets and then one needs to wait for 4-5 minutes for the hole to get recharged. Moreover, the water hole lacks a parapet around as a result of which dirt and dust from the road and plastics fly into it, making the water unclean and unsafe for consumption or even personal hygiene. Sometimes, women walk long distances to secure water from other sources, with some even having to beg for water, requesting water access from hotels, houses, shops, etc. The circumstances facing the Pardhi community described above thwart enjoyment of their human right to water by impinging upon the norms of ‘availability’, ‘quality’, ‘physical accessibility’ and ‘non-discrimination’.

Filling water for drinking and cooking from a spring

In order to escape the expenses for purchasing water for everyday use, poor slum dwellers are forced to undertake hardships, bringing water from long distances. In one of the slum settlements where municipal water supply is absent, field study by the authors found that the residents, especially girl children, walk everyday around 2.5 kms one side to procure water from a spring, as shown in the photo above. This is not a natural spring, but the source is leakage from a water main. The water is sweet but oozes out as a trickle, making water collection a tedious time-consuming task. Further, since the spring is located in a creek, water can be collected only during the low tide. As a result, children who engage in water procurement from the spring end up spending a major part of the day in the activity, hampering the possibility of attending school. The hardships faced by the children described here thwart the human right to water norms of ‘non-discrimination’, ‘physical accessibility’ as well as ‘availability’ of water. Even ‘quality’ of the water procured is not guaranteed.

Rush at the distant spring shown before for collecting the slowly trickling water

Returning home with loads of spring water across busy railway tracks

Procuring water from the spring described before poses multiple challenges and risks for the children who unfailingly engage in this activity on daily basis. Apart from being time-consuming, carriage of heavy loads of water over a long distance exposes children to risk of neck and spinal injuries. Further, walking across busy railway tracks for the purpose brings the risk of accidents which can be life-threatening. Manually hauling water over long distance by children through unsafe surroundings leads to infringement of the human right to water norms of ‘physical accessibility’, ‘non-discrimination’, as well as ‘availability’ of water for the poor slum dwellers.

A tapless public tapstand for the Warli tribe residing in Mumbai

Mumbai is home to more than 150,000 members of the primitive Warli tribe, about half of whom live on a single huge denuded hillock which used to be a dense forest in the past and the basis of their livelihoods and resources essential for life. For facilitating water access to the members of Warli community, the government developed a plan for a borewell-based pipeline supply in the locality, with public standposts having taps. But due to extreme of corruption, as reported by the local Warli community, the planned borewell was never dug and the associated pipeline connections never laid. The only evidence of the water supply plan is the tapless standpost shown in the above photo, which was never completed. As a result, even after several decades of independence, the Warli community of Mumbai at this location continue to lack access to safe and adequate water for fulfilling their domestic and personal needs. The situation faced by the Warli community with respect to water reflects infringement of the human right to water norms of ‘non-discrimination’, ‘physical accessibility’ as well as ‘availability’ of water for the poor slum dwellers.

A Warli woman taking polluted water from a ditch in the absence of proper water supply

Through the decades, the Warli community in the hilly terrains of Mumbai has depended upon springs and shallow ditches called ‘bauri’ as traditional water sources. Bauris are dug on the slope of a hill or on plain land and filled by rain water and seepage from groundwater. These sources were regularly cleaned and maintained by the community and therefore considered by them as safe for drinking and other personal and domestic uses. In the Warli settlement visited during the field study by the authors, there exists a bauri - shown in the photo above – which is the only water source for the people. However, in the recent years, the quality of water in this bauri has come to be degraded due development of a big dairy next to the settlement. Surface run-off as well as contamination of the groundwater has come to seriously pollute the water seeping into the bauri. This makes the water unsafe for consumption, but having no other alternative, the community is forced to use this polluted water, thus thwarting the ‘quality’ norm underlying enjoyment of the human right to water. Also, the norms of ‘non-discrimination’, ‘physical accessibility’ as well as ‘availability’ of water for the poor tribal community are infringed.

The above presentation overtly clarifies how for about half the population of Mumbai – those residing in the slums – enjoyment of the human right to water is a distant dream. Regarding the first norm for enjoyment of the right - availability, the challenges especially in the notified slums include erratic supply, low pressure and short duration. Consequently, the quantity available is far too little for fulfilling the basic daily needs, namely drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation, and personal and household hygiene. In the unserved settlements, the situation is worse, as sufficient and continuous water supply remains largely missing. Regarding the second norm about quality of the water, contamination in the municipal water received is common due to leakages in the old pipelines, often resulting in diseases such as jaundice, typhoid, malaria, dengue, tuberculosis and diarrhea. In the unserved slum settlements, water quality is a perpetual issue since people have little choice than to revert to various kinds of unsafe water sources. Besides, according to a report of the Central Groundwater Board (2013), groundwater as well as surface water in the city is polluted due to release of untreated sewage and industrial effluents, and groundwater in some areas is affected by salinity ingress, which make the groundwater non-potable. Concerning the third norm of physical accessibility, the situation is grim, with serious challenges including hauling of water over long distances, up steep stairs or on pitch dark pathways in the night. Further, the population residing in non-notified settlements have to depend upon pipeline leakages, unsafe well water, unreliable tanker water or other odd sources which may be distant and require water purchase, raising challenges to human right to water norms of availability, physical accessibility, quality as well as affordability. Infringement of the availability and affordability norms may also occur in the notified slums especially in the dry season when water cuts are imposed in the city.

The norm of non-discrimination and equity is perhaps the biggest challenge in Mumbai, exhibiting multiple dimensions. On the whole, inequity is suffered by the 42% slum households in the city, with the well-off socio-economic sections residing in the posh localities receiving the lion’s share of the water supply. There is further inequity between the residents of notified and non-notified slums, with the former having access to municipal services and hence better placed with respect to water access. In terms of gender discrimination, it is primarily the women and girls who suffer. Further, children suffer substantially both by virtue of inadequate access to clean water and engagement in water procurement, which adversely impact their health, general growth and development, and education. Also evident is discrimination against tribal and socio-economically weaker sections traditionally residing in the city, such as the Pardhi and Warli. Information accessibility and transparency regarding water supply, which is the final norm laid down for enjoyment of the human right to water is poorly developed in the city in general. It is also to be noted that challenges in enjoying the human right to water in Mumbai is not restricted to the slum residents and weaker sections alone. As mentioned before, there is a general shortfall of 400 MLD in the city, which becomes even more acute during the dry season. In 2018, as a result of insufficient rain, MCGM cut the water supply by 10% for all entities including residential, commercial and other establishments. Earlier in 2014 and 2015 too, MCGM had imposed 20% water cut for residential properties. While such water cuts affect the human right to water of all citizens, the worst to suffer are the already disadvantaged sections.

Problems with enjoyment of the human right to water thwarts the enjoyment of several concomitant human rights by the residents of Mumbai and this in turn poses a great challenge for achieving the water-related SDGs. It is high time for MCGM and the State government to look deeper into the current limitations, redesign the ongoing efforts and ensure effective implementation of the planned action so as to address issues like corruption and inequity. Otherwise, the human right to water of women, men and children in the commercial capital of India will continue to remain unrealized, in turn thwarting their other related human rights such as that to health, education, sustainable livelihoods, and over-all development.