Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2019

Status of the Human Right to Water in Nagaland

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

30 September, 2019

The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015) obliges governments to ensure that no one is left behind in access to safe and affordable drinking water, which in turn, hinges upon realization of the human right to water. According to the UN framework, the human right to water entitles everyone, without discrimination, to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic use. The norms and goals set up in India within the scope of this framework have been highlighted in a previous story (16 April 2019), followed by presentations on the status of the right in India (15 May 2019) and in Delhi (15 June 2019) and Mumbai (29 July 2019). The situation in rural India has also been presented through the case of Gujarat (31 August 2019). This photo story aims to explore the status of human right to water in the hilly regions of India, through a focus on Nagaland, a predominantly mountainous state. Recognized as one of the 'Seven Sister States' of northeastern India, Nagaland is tight-packed with north-south aligned ranges defined by steep slopes and narrow valleys. The altitude of the state varies from 100 up to 3,840 m. Rainfall is considerably high, with the average annual varying between 2,000 to 2,500 mm. However, despite the high rainfall, Nagaland's Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) – the agency responsible for supplying water for domestic and personal use – notes that many rural and urban habitations lack viable water sources, and their depletion from the wet to dry season is a common phenomenon. Most water sources in Nagaland are surface water based, such as rivers, streams, springs and ponds, and the supply systems are either gravity-fed or based on pumping. Thus, for a good proportion of the over 1.4 million rural population and the 0.6 million urbanites, 'availability' of water round the year is a significant challenge. Moreover, the PHED's 'coverage' for water supply is low in both rural and urban pockets. According to the 2018-2019 Annual Report of Government of India (GoI), only 51% rural habitations in Nagaland are 'fully covered' with access to 40 liters per capita per day (lpcd) of safe drinking water throughout the year available within 100 m (horizontal/vertical) from the household. Further, in terms of 'physical access', the census of 2011 shows that only about 29% of total households enjoy access to a source within the premises, and a near equal number are dependent on a 'distant' source, which implies traversing a distance of 100 m or more, mostly on hilly terrains. Among rural households, this figure is only 20% while the corresponding figure for urban households is about 50%. As many as one-fifth of urban households report water procurement from 'distant' sources. In terms of piped water supply, while about 47% of total households in the state reported access in 2011, less than 13% of these enjoyed supply from a treated source. The remaining population depend upon other sources such as untreated tapwater, wells, handpumps, tubewells, rivers and springs, where the quality of water delivered may be uncertain. A report from the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India on Nagaland's Social, Economic, Revenue and General Sectors (2018) further reveals that only 4.9% coverage exists for piped water supply within rural household premises, while according to national standards, the target coverage by 2017 was 35%. The CAG report also notes shortfall in regular monitoring of water quality and prompt action for mitigation wherever needed. Further, information accessibility related to water supply is poor, and insufficient coverage and seasonality of water availability imposes additional financial burden on the urban and rural populace, who may be forced to privately buy water in the absence of regular supplies. Such a scenario throws up important concerns regarding enjoyment of the human right to water in Nagaland, as all the essential norms, namely, availability, safety, physical accessibility, non-discrimination, information accessibility and affordability are significantly thwarted. The photo story delves deeper into the state of enjoyment of these norms in the rural and urban pockets of Nagaland. The title photo depicts women carrying heavy loads of water on the back in traditional bamboo pipe containers in Tuensang district.

A gravity-based piped water supply network in a village in Mokokchung district

In Nagaland, the total drinking water requirement for the whole state is estimated to be 96.26 million liters per day (MLD) with rural areas requiring 39.96 MLD and urban areas 56.30 MLD. Towards fulfilling this demand and facilitating people's access to water, the PHED has been engaged in installation of piped water networks in rural and urban habitations, primarily sourced from springs and surface water sources. One of these networks is shown in the photo above. However, according to different sources, including the government's own reports, despite the efforts, water supply 'coverage' continues to remain poor. According to a Performance Audit of the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP) conducted by the CAG (2018), about 50% rural households do not have access to adequate quantity of safe drinking water. Further, as per the census of 2011, piped water supply is not available to 53% households in the state within or outside the domestic premises. Recent figures from a senior scientist of the Nagaland State and Technology Council (NASTEC), Department of Science & Technology, (in contrast to the GoI figure stated earlier), point out that as many as 87% villages are yet to be ensured 100% water supply, as per the status on April 1, 2017. The situation in the urban areas is no better. For example, in the capital city of Kohima, against a total demand of 11 MLD, only 1.5 MLD is reported to be supplied, which is expected to increase to 4.5 MLD on completion of a new project, still leaving a huge deficit.

Pipelines for water distribution to local households in a village in Mokokchung district

While the site of pipelines leading into local households or public points, as shown in the above photo, is a welcome sight, an important reality in Nagaland is their seasonality. Since these schemes often draw water from springs and rivers that are seasonal, many piped networks become progressively dry during the lean season, which may extend up to 6 months, starting from November. Thus, at first the supply may be reduced to a limited number of days in a week, and later may be altogether discontinued. In the capital city of Kohima, water supply is officially reported as limited to once in 3-7 days during the lean season. This deepens people's misery, thwarting the 'availability' norm of human right to water.

Containers lined up at a rural public tapstand in Mokokchung district

Installation of a piped water scheme in a village or town in Nagaland does not ensure availability of water. The number of tap water connections within domestic premises in both rural and urban habitations is low, as noted before, and many households need to fetch water from public tapstands. However, even public tapstands may be few, making several households dependent on a single point. This leads to long queues as depicted in the photo above. Moreover, the supply is often irregular and at low pressure, leading to rush and conflicts while procuring water. At the end, some households may still remain without water. This flouts the 'non-discrimination' norm for exercising human right to water.

Seeking help from a neighbor for water access in Dimapur city

Many houses that lack access to PHED's water supply have their own private sources, thus having access within domestic premises. However, the seasonality of water availability affects even private sources. One solution under such circumstances is to depend on neighbors who have better access. Dimapur is the only city in Nagaland located in the plains but here too drinking water sources are unreliable. The household shown in the photo above owns a private well, but this dries up during the summer season. To tide over the crisis, they are forced to seek support from a next-door neighbor who has a deeper tubewell. This kind neighbor – a businessman – allows them to draw water from his tubewell to fulfill their basic necessities. However, the process of procuring water is full of hardships and requires team work, as it involves manually hauling water from the ground floor to higher up into their own residential quarters. The situation highlights problems with fulfilment of the 'availability' and 'physical accessibility' norms of the human right to water framework.

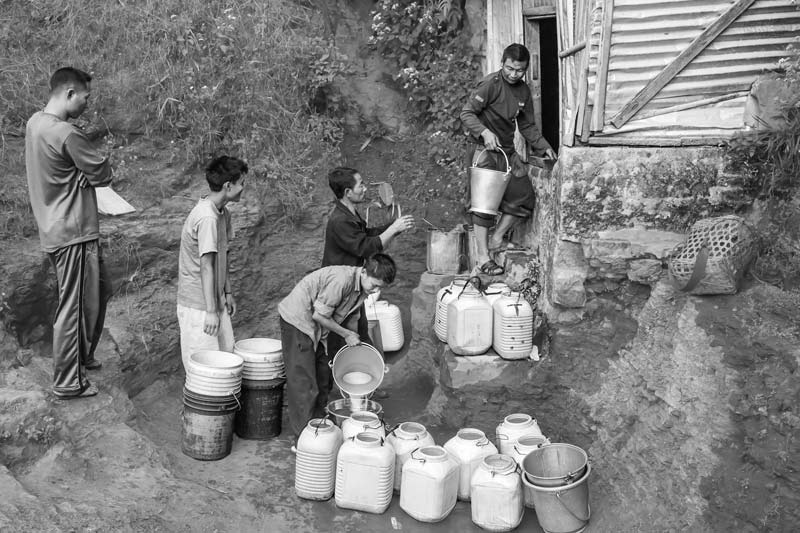

Rationing of water from a protected spring-fed tank in Mokokchung town

For households that neither have access to the government pipeline nor own a private source, the only option is to procure water from outside. According to the census of 2011, as many as 71% households in Nagaland depend upon a water source outside the domestic premises, the figure being as high as 80% for rural households, while for urban households it is nearly 50%. At many places in towns and villages, the water emerging from natural springs is stored in protected tanks by the community or the village council, which can be procured by the local households. During and soon after the monsoon season (July-October), the spring-fed tanks recharge fast and there is generally plentiful of water to collect as and when needed. But soon after, the recharge starts slowing down, and water becomes an increasingly precious resource. At this juncture, the protected tanks may be put under lock, and the households dependent on it become entitled to a limited daily or weekly ration depending on the number of household members and the water quantity available for distribution. Such a situation is depicted in the photo above. Rationing of water depicts a situation of violation of the 'availability' norm of human right to water.

'Scooping' water out of a nearly dried protected spring-fed tank in Mokokchung town

As the lean season progresses, the water recharge in the spring-fed tanks almost stops and the scene looks like the one depicted in the above photo. In the absence of any alternate means to procure water, this lady has entered a protected tank to scoop out the few drops that still occasionally collect inside. This is an alarming depiction of the violation of the human right to water norm of 'availability'. Further, the little amount of water available in the base of the tank is obviously mixed with sand and other particulate matter, which implies degraded water quality. Also, walking into the tank wearing footwear further introduces dirt, posing further risk to the water quality. Thus, even the human right to water norm of 'safety' of the water gets challenged.

Extracting drops of precious water from a dried-up unprotected spring-fed tank in Mokokchung district

In some places, the local community or the village council has constructed open spring-fed tanks. These meet the same fate as the protected tanks with respect to seasonality of water availability, and ultimately dry up to the extent that water can be no longer be gainfully extracted. One such tank is depicted in the photo above where men and children are lifting water out with ladles. This situation again depicts how seriously the human right to water norm of 'availability' gets flouted in Nagaland. Additionally, even the 'safety' norm is challenged because the little amount of the recharged water is mixed with soil particles in the base of the tank. Also, the men and children have entered the tank wearing footwear, bringing dirt inside, which obviously pollutes the water.

Venturing out around midnight in search of water in Mokokchung district

As the lean season progresses, the spring-fed tanks recharge very slowly and may take hours to fill enough for providing a bucketful of water. Often the little water available in such drying tanks in the vicinity is collected by women and children during the day. But this water at home may still be insufficient, and under such circumstances, or when the tanks in the vicinity completely dry up, men assist in water procurement. They go looking for distant water sources late in the night that might be in the form of undisturbed unused springs that have recharged during the evening. One such scene of men proceeding to fetch water around midnight on the hills is shown in the photo above, which is representative of the extent of violation of the 'physical accessibility' norm under the human right to water framework. Apart from the hardship in hauling the multiple water containers carried by them, what is alarming is the risk of injury they face while trekking with heavy water containers in the pitch dark up the slopes.

Women hauling water up a steep slope in Tuensang district

As noted before, for greater part of the year, the drinking water sources located within the rural habitations do not yield water. As a result, women as the domestic water managers undergo the regular hardship of carrying water on their backs up steep hill slopes, since their villages are located on hilltops while the alternate water sources exist down the slopes. These sources are generally springs, streams, ponds and tanks. Very often they have to traverse vertical distances longer than 100 m which is stipulated as the standard for reckoning 'coverage' under the rural and urban water supply programs in India. Irrespective of age, women are seen to carry heavy loads of water in bamboo pipes kept inside bamboo baskets. Carrying of heavy water loads on the steep slopes exposes them to the risk of physical injury and it also results in huge loss of productive time. The extent of time invested gets higher as the dry season progresses, with women needing to search for sources further and further down the hill. This thwarts not only realization of the 'physical accessibility' and 'non-discrimination' norms of the human right to water but also interferes with enjoyment of several other rights of these women such as health, livelihood and development.

Children carrying heavy water loads up a hilly track in Tuensang district

The dependence of households on springs, streams, ponds and tanks in rural and urban Nagaland alike is quite high, which in the census of 2011 was reported as more than one-fifth. Considering that an individual is seen to require a basic minimum of 40 l according to the Indian rural water supply standards, absence of water source at home or in the locality implies that a large amount of water requires to be transported to a household on a day-to-day basis. Consequently, children commonly join the task, carrying loadfuls of water on their backs in bamboo pipes and plastic cans kept inside bamboo baskets. The drudgery of carrying heavy water loads exposes children to risks of spinal and neck injuries, apart from stunted growth and loss of valuable study time. This in turn hampers enjoyment of their human rights to health and education, besides the human right to water norms of 'physical accessibility' and 'non-discrimination' against children.

Small children procuring water from an unprotected spring-fed pool early in the morning in Tuensang district

The situation of water access is so poor in the rural and urban households of Nagaland for the major part of the year that even small children assist their families in procuring water. Early in the morning when adults may have other domestic engagement, but the spring-fed water tanks and pools are recharged, small children are often sent out to fetch buckets of water, as shown in the photo above. This disturbs their sleep or school time, is tiring and poses health risks. Further, as seen here, the water collected in the pool is muddy, and the children are almost descending into main pool wearing footwear which can further introduce contamination in the water. In relation to the human right to water, the overall situation is violative of the norms of 'non-discrimination' against children as well as 'safety' of the water procured.

Children of a residential school procuring water for daily use from a distant source in Mon district

Apart from poor access to drinking water at home, water access in even schools and child-care centres (Anganwadis) is poor in Nagaland. The CAG report (2018) on NRDWP found a shortfall of 54% in Nagaland in this regard. As a result of absence of water supply at school, children may be required to procure water from alternate sources outside. In residential schools, they may even need to procure water for their personal use as shown in the photo above. This disturbs their school routine and study time and also hampers their access to adequate and safe water in school. This denotes a violation of the norm of 'non-discrimination' against children at educational institutions.

A visibly unclean spring-fed drinking water source in Zunheboto district

Apart from the challenge of water quantity, the rural and urban populace of Nagaland also face quality challenges. Unfortunately, monitoring of water quality at public water supply points has been poor in Nagaland, as noted by CAG (2018). Also, community water treatment plants have not been installed in the state, as noted by the CAG. But an even more serious problem is the degraded water quality at the alternate water sources frequented by people during the lean season. At these sources, which are often ill-maintained, the water can be visibly dirty and contaminated, as shown in the photo above, However, in the absence of cleaner and safer sources, people are forced to procure water from contaminated sources, as depicted in the photographs below. This is violative of the norm of 'safety' of water for enjoying the human right to water.

Procuring drinking water in the morning from the source shown above

Filling buckets with the unclean water from the source shown above

Children taking water in the evening from the same spring-fed source shown above

As noted before, spring-fed water sources recharge slowly. Thus, in the morning, these may be holding larger water stores, which gets depleted as the day progresses, with people regularly coming to procure water. The spring-fed source shown in the previous photo has a small capacity and by the evening, it gets almost exhausted so that people start tramping inside its base in a bid to pick up the little remaining water as is shown to be done by the children. Further, they have entered inside with footwear on which adds to the pollution in the pool and degrades the quality of the water they collect. Thus, both 'availability' and 'safety' norms under the human right to water framework get thwarted.

A bunch of private water cables running across a long row of houses in the capital city Kohima

According to Kohima's 'smart city' proposal (2015), there was total supply of 2.3 MLD at the rate of 305 l/household, which paints quite a rosy picture, given the general scene of water scarcity in the state. However, an Asian Development Bank (ADB) report from the same year clarifies that only one-fifth of the households of the city are connected to the PHED water supply system, that too in limited areas. Under such circumstances, a substantial number of the uncovered households depend upon expensive private water cable networks that distribute water through thin plastic pipes crisscrossing the city in bunches. These networks are sourced from springs and streams up in the hills which are directly tapped through the pipes and distributed through gravity at the local scale. The private water cable network is expensive and includes a nonrefundable installation fee and additional monthly bills, which may vary from one part of the city to another. Non-coverage under the PHED piped network is violative of the norm of 'non-discrimination', but while the expensive private cable network facilitates users with the norm of 'physical accessibility' within the human right to water framework, because of its high cost, it hampers the norm of 'affordability'. On the whole, this leads to violation of the human right to water of many residing in the city.

Water cables hanging dangerously over electricity and telephone poles in Kohima city

The private water cables lack supporting infrastructure and are just bundled together and hung-over telephone and electricity poles along the roads, as shown in the photo above. The heavy load of the water-containing cable bundles poses considerable risk of electric shock to the residents and passers-by underneath, thus becoming a life-threat. And yet these cable networks are unable to secure the human right to water of the residents of Kohima, since their source springs start drying up as the lean season sets in. Thus, the human right to water norm of 'availability' gets violated, ultimately leaving the users without water access for a considerable period of the year.

Tanks for private water supply being filled from a spring in Kohima district

When the water pipelines and private cables in the city run dry or springs and streams in the villages dry up, one of the solutions adopted by some residents is to buy water from private tankers, as shown in the photo above. These tankers commonly fill water from the more perennial spring and river sources. However, this is an expensive option which can cost about Rs. 75 (more than 1 USD) for 20 litres or over Rs. 700 (approx. 10 USD) for thousand liters or more. This may force some residents to compromise on certain other essential costs, since a family of five-six members may spend Rs 3,000-4,000 (approx. 42-57 USD) or even more for buying water. This contravenes the 'affordability' norm essential for enjoyment of the human right to water.

Performing laundry at a distant stream in the forests along Dimapur-Kohima National Highway

Unavailability or unaffordability of water, particularly for purposes that require bulk volumes (such as laundry), force people to venture out of home in search of water sources in distant forests. This is equally true for urban as well as rural areas. These sources could be nearby or distant, and it may not always be possible to use these on a daily basis. An instance is shown in the photo above where a woman is seen washing a week's laundry at a hill stream in the midst of a forest. According to information provided by her, since they do not have access to enough water at home during the lean season, she collects the family's dirty clothes, and travels to this spot generally once a week to wash them.

This photo story has illustrated the status of enjoyment of the human right to water in the rural and urban areas of Nagaland. It is obvious that the government has been unable to secure the right of the citizens to access water in sufficient quantity, with appropriate quality and at an affordable cost. It has also not been able to ensure ease of physical access to water for communities that inhabit difficult hilly terrains in a state which is primarily mountainous. Most of the rural communities in Nagaland reside on hilltops which adds to their woes. The story shows that while absence of adequate 'coverage' through PHED supplies itself violates the right of a large chunk of the population, even for those who have been ostensibly 'covered', enjoyment of the right becomes increasingly difficult as the lean season progresses. While the average annual rainfall in the state is very high, and therefore the water resources received on its land area is large, the people live in a serious state of water scarcity for a large part of the year. Also, as the CAG reports show, monitoring of the water quality has been poor even when access to safe water is clearly a serious challenge. The story has adequately illustrated how the different norms essential for enjoying the human right to water remain unfulfilled for the residents of rural as well as urban communities.

Lack of access to safe and adequate water for domestic and personal use enhances health risks in multiple ways, ranging from water-borne infections to water-washed diseases, primarily diarrhea, parasitic infestation, infective hepatitis, enteric fever and skin diseases. The drudgery of hauling heavy water loads over long vertical distances on the steep hills enhances in general the risk of neck and spinal injury and injuries from slipping and falling, besides stunted growth among children. The burden on women and children, especially girls, is high in this regard and breeds societal inequity. It further thwarts education of children, many of who waste valuable hours in procuring water and may even lack access to safe water at their educational institutions. Women's time investment in procuring water prevents them from engaging in gainful economic pursuits. Further, scarcity of water thwarts them from undertaking their domestic chores effectively such as washing and cleaning in a hygienic manner. The quality and drudgery further reduces physical capacities for undertaking economic activities efficiently. Wherever men participate in water procurement, they face similar consequences. For those who try to improve access by paying for water, the expenses associated with options like private water cable supply or purchase of water tankers, it may result in compromising other essential household expenses such as children's education or food. Thus, inability to enjoy the human right to water leads to the inability to ensure several other human rights of the men, women and children in the state through multiple pathways.

Given this scenario, it is high time that the government should wake up and strive to find ways to augment the water availability in the hills round the year, improve people's access to water and protect its quality. Otherwise, given the risks posed by climate change, the impact of which is already being experienced in Nagaland, enjoyment of the right will become increasingly difficult, ultimately thwarting sustainable development in the state. The picture drawn here is no isolated case but is indeed representative of the situation in many other hilly regions of India – Himalayan and non-Himalayan – where people similarly face challenges in exercising their human right to water. The case of Nagaland should serve as an eye-opener to the country, making the government, citizens and all related actors to join forces and attempt to overcome the barriers to human right to water in these areas.