Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Traditional Water Supply Science and Technology of India

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 December, 2016

In India, water supply for drinking and other domestic uses has been traditionally made possible across diverse geographical and climatic zones through different local forms of science and technology. These forms, found widely across tribal as well as non-tribal communities, are primarily based on the natural water cycle wherein raindrops are seen as the source of water reserves on earth which can be harnessed for fulfilling human needs. While the creators of the traditional technologies have often been men, their design, location and form have primarily aimed to facilitate women, who widely shoulder the responsibility of domestic water management. In the arid and semi-arid regions in western India where rainfall is limited and deep aquifers are saline, the technology basically aims at storage and use of rainwater, with additional focus on recharge of shallow aquifers which can be harnessed during the dry season. In the parts of peninsular India where rainfall is low to moderate and the river network is poor, storage and use of rainwater has again been the emphasis. In fact, tanks connected in series are an important characteristic here, providing water for direct use as well as aquifer recharge. In parts of Chotanagpur Plateau, underground streams as well as rainwater flow are directed into flat valleys where ponds are dug or the recharged groundwater is harnessed. Important aspects of the local science in all such areas comprise knowledge about the appropriate topography so that maximum water flows can be diverted and stored, and about the appropriate soil quality for allowing water retention for a longer period. In the northern and north-eastern regions where rainfall is plenty but terrain is mountainous, springs are an important water supply source that are harnessed in different ways using simple technologies. The local science here concerns knowledge about the topography and the underground water movements that enable identification of appropriate spots for harnessing the springs. On the whole, the traditional water supply science represents a way of perceiving the world that promotes balance with nature, thereby supporting technologies that are need-based, non-exploitative and sustainable, even helping communities ‘climate-proof’ themselves. This photo story presents a virtual tour across a selection of traditional water supply science and technology from different corners of the country. The title photo depicts a circular stepwell in a village in Kolar district, Karnataka, an area known to be drought-prone with a semi-arid climate. However, owing to a rich network of over 3,000 tanks that store rainwater and recharge wells, water supply has always been secured in the villages. Stepwells here aim to facilitate water access through dry seasons and low rainfall years.

A reservoir constructed for collecting rainwater in the historical city of Dholavira in Kutch district, Gujarat

Dholavira, located in the Great Rann of Kutch, is one of the grandest cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, dating back to 2650 BCE. It lies in an area that comprises a flat desert of salty clay, presently receiving less than 400 mm annual rainfall. The residents of the city developed an ingenious system of rainwater harvesting to support life in this parched landscape, where sweet water is scanty. The water conservation system here consists of reservoirs and channels built completely of stone, which are in fact the oldest known in the world. There exist sixteen or more water reservoirs of varying size that were used for storing fresh water brought by rains or to store water diverted from two nearby rivulets. The system was a response to the desert climate and conditions of Kutch, where apart from low rainfall and groundwater salinity, drought years are common. The reservoirs are large, measuring about 7 m deep and 79 m long, and are cut through stone vertically. These actually skirt the city, protecting it from all sides. Some of the reservoirs had steps to reach down to the water once the level receded.

A historical well from the Indus Valley Civilization at Dholavira in Kutch district, Gujarat

Well is one of the oldest and the most widespread traditional water supply source in India, based on the principle of harvesting underground aquifers by digging or excavating into the ground. The well water is drawn by using a rope and containers that may be pulled just by hand or raised mechanically using a pulley. Wells are generally lined with brick or stone to impart stability. Different forms of wells of varying depths and sizes exist in different areas and known by different names, harvesting shallow to deep aquifers depending upon the depth of the water table. One of the earliest evidences of wells in India are found at the Indus Valley Civilization site of Dholavira which is older than 4000 years. Here large water reservoirs that harvested rainwater were connected to rock cut wells that filled cisterns for drinking and bathing, making water available for domestic uses round the year even in a dry and drought-prone area.

A series of shallow wells called kuiyan around a pond (johad) outside a village settlement in Thar Desert, Bikaner district, Rajasthan

In the Thar Desert in arid western Rajasthan, rainwater is a very precious resource since the groundwater is deep and saline and streams are rare. Therefore, every drop of rain is collected and carefully preserved primarily for drinking purposes. Villages here depend on local catchments where water collects in ponds that are created in concurrence with the existing natural slopes and soil type. In some areas, this collected water may be fetched by women directly for drinking and cooking purposes as long as it lasts, while in others this water may be used only by animals. In either case, the stored water also helps recharge shallow aquifers around that supply drinking water until almost the next summer season. In Bikaner district, the average annual rainfall is only 240 mm, but when carefully harvested, this scanty rainfall supports vibrant village communities throughout the year. Locally known as paaytan, village catchments are cleaned every year before the onset of rains and strict social rules are followed about usage of the catchment area by the community. The johad shown in the photograph is about 400 years old and is used by animals for drinking water.

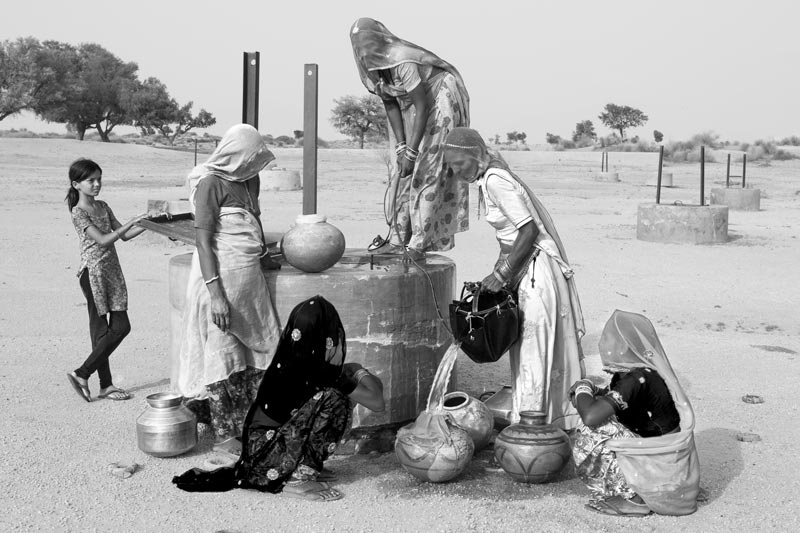

‘Sweet’ drinking water being collected from one of the kuiyans shown above in Thar Desert, Bikaner district, Rajasthan

In western Rajasthan, the recharge area adjoining a pond is locally referred to as taanda where shallow wells having depth up to 5-15 meters are dug from which women are able to procure sweet, cool and safe water for about 8-10 months in the year. In the taanda shown in the previous photograph, 100-150 kuiyans exist, of which about 50 are presently in use. The diameter at the base of the kuiyans in this taanda is 7-8 feet while the top is narrower. The water supplied by these kuiyans is enough to fulfil the drinking water needs of the village consisting of about 400 households. Drinking water drawn from the kuiyans is considered to be clean and safe as any impurities and germs are known to be filtered through the soil layers.

An underground water storage tank (kund) with its large catchment on the outskirts of a village in Thar Desert, Bikaner district, Rajasthan

The scanty rainwater in the Thar Desert in western Rajasthan is safely stored inside covered underground tanks called kund/kundi in Bikaner and tanka in Jaisalmer area respectively. These represent an ingenious technology for tackling drinking water problems from both quantity and quality perspectives. Usually constructed with local materials or cement, these structures secure people’s access to convenient, clean and sweet drinking water even over drought periods. Kundis generally have capacity up to about 1000 liters while kunds are larger. The former are generally a water source at home meant for day-to-day use, while the latter secure longer-term storage, whether privately at home or at the community scale. These can be constructed in different places like courtyards, in front of houses and temples, in open agricultural fields, barren lands etc. The kund/kundi/tanka generally consists of a saucer-shaped catchment area with a gentle slope towards the center where the tank having inlets for water is situated. The top is usually covered with a lid from where water can be drawn out with a bucket. Before the onset of rains every year, meticulous care is taken to clean up the catchment. Cattle grazing and entry with shoes into the catchment area is generally prohibited.

Water being collected from the kund shown above in Thar Desert, Bikaner district, Rajasthan

The proximity of a kund to the village saves time and effort in searching for drinking water. In fact, without kund/kundi, people in this area may need to undertake 10-15 km round trips to meet their water needs. This kund is community source made of lime (chuna) and the capacity is more than 300,000 liters. 20-25 households can drink water from here round the year, and still be left with reserves for the next year. The depth is around 30 meters and width about 6 meters.

Jhalra baori, a stepwell in Thar Desert, Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Stepwell is yet another traditional technological innovation for coping with seasonal fluctuations in water availability and tiding over drought years in the arid and semi-arid regions. These may be described as large wells or small ponds that collect rainwater and the local runoff and possess sets of steps for facilitating access to the water which may undergo significant fluctuation of level across different seasons and years. Many stepwells have an adjoining deeper well or one inside it that is recharged by its water and supplies drinking water after the stepwell has dried up. Known by a variety of local names, stepwells exist in a number of states notably Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and the Union Territory of Delhi. In Rajasthan the local name for stepwell is baori. Jhalra Baori is a big stepwell constructed by the local king for royal as well as public use in an area where the average annual rainfall is only 182 mm, one of the lowest in the country. A shallow well (beri) exists inside the baori which is submerged under water in the photograph. Depth of the baori is 40-50 feet while the beri is much deeper. Some stepwells in India are very large, elaborate and of great architectural significance which also serve as places for social gatherings and religious ceremonies.

Girls fetching ‘sweet’water from a pond in Kutch district, Gujarat

In Gujarat, groundwater salinity is a significant problem which has necessitated the development of surface water sources based on rainwater harvesting. Many villages have ponds that collect rainwater which is directly fetched by women and girls for drinking and other domestic purposes. Since the pond water is only seasonal, there may also exist a well inside a pond (as in this one) which gets recharged by the pond and supplies drinking water after drying up of the pond.

Drinking water being fetched from a well located at the base of a valley in a Munda tribal village in West Singhbhum district, Jharkhand

In Jharkhand in the Chotanagpur plateau region, the indigenous water management system of the Munda tribe has been very efficiently designed to harvest the plentiful rains that average around 1300 mm a year. The runoff over the ground as well as underground water streams in the Munda villages are made to converge at the base of flat valleys. While flowing over the undulating slopes, this water helps in irrigation of crops, and at the base of the valleys it additionally enables recharging of shallow aquifers that provide clean drinking water to the adjacent village communities. The deeper aquifers in the area often contain high iron and other contaminants and therefore handpumps in the village settlements are commonly rejected for drinking purposes in favor of these shallow rainwater-fed wells called doba which provide drinking water supply round the year.

Water being procured by Konyak tribal children from a hillside spring in Mon district, Nagaland

Springs have been traditionally used for water supplies in the mountainous and hilly regions of India as reliable and inexpensive sources of domestic water. The hilly north-eastern India is one of the highest rainfall-receiving regions in the world with an average annual rainfall of 2068 mm. This abundant rainfall is tapped by the local tribal communities for water supply through springs which occur wherever groundwater flows out from the earth’s surface along hillsides, low-lying areas, or at the base of slopes. In Nagaland, springs are the most common source of domestic water in rural and urban communities for a major part of the year. Water may be directly collected from springs for drinking and other domestic uses or harvested through small or big piped networks that operate on gravity basis. Such piped networks exist in Kohima and other towns as well as in a good number of villages. In the above photograph, the spring has been made more user-friendly by inserting a bamboo pipe to direct the water flow so that containers can be filled more easily.

A spring being used for domestic purposes by a Khasi tribal woman in Sohra (Cherrapunji), East Khasi Hills district, Meghalaya

Meghalaya (translated as 'the abode of clouds') is the wettest region of India, with Sohra (Cherrapunji) which received 22,987 mm of rainfall in a year (in 1861), holding the title of the wettest place of the world until recent past. Another village Mawsynram now holds this world record with an average annual rainfall of 11,690 mm. Given the abundance of rainfall in the state and the predominantly hilly terrain, springs have been widely tapped as water supply sources. Springs feed the piped water supply in Sohra town. Besides, natural springs are directly used by the local tribal communities for drinking and other domestic purposes such as washing and bathing. The spring shown in the above photo has been improvised by fixing a tin sheet so as to channelize the flowing water in order to ease its use.

Water being fetched by an old Ao tribal woman from a small tank that collects spring water at the base of a hill in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

Sometimes the spring flow in these hill states may be small so that it is not sufficient to fill containers directly. In such cases, small tanks are created by raising an embankment on one side of the hill that are then recharged by the spring. Drinking water is collected from such recharged tanks.

Chahal – a protected spring in a village in district Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakhand

The Himalayan state of Uttarakhand is enndowed with a high average annual rainfall of 1229 mm which helps feed several natural springs that are tapped by local communities for fulfilling their drinking water needs. These springs may be protected by creating a concrete structure to prevent water pollution from the hill slopes. Religious value is often attached to these structures and washing, bathing and polluting the source in any way is prohibited. The resultant structure is called chahal which not only provides drinking water but the drainage is collected further down first for providing drinking water for animals and later for irrigating kitchen gardens downstream.

Tangi Kula – a sacred tank in Melkote town, Mandya district, Karnataka from where drinking water is being fetched by a priest

Several districts in Peninsular India particularly in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana are located in the rain-shadow area, receiving low annual rainfall in the range of 400-750 mm. These areas are highly dependent upon rainwater harvested through tanks and ponds that may also be connected in series. These tanks may be associated with temples and hence regarded as ‘sacred’ or be used for secular purposes including irrigation and domestic water supply. In Melkote, a series of six sacred tanks harvest rainwater. Akka and Tangi Kula are twin sacred tanks in the series located next to each other, literally translated as the elder and younger sister ponds. Tangi kula is a source of drinking water and washing, cleaning and bathing is prohibited here. These tanks are recharged through underground sources based on the locally received rainfall.

The selection of water supply science and technology presented in this story offers important food for thought. It is evident that while the underlying scientific knowledge is based on certain common principles, there exist context-based variations across different zones, making the related technologies functionally adaptive to the local geographies, climates, hydrology, natural resources and skills base. Further, since the traditional science and the concomitant technology are a result of observation, analysis, experimentation and experience through generations; this is robust, time-tested and hence reliable and sustainable. This is also evident on ground of being rooted in the principle of ‘balance with nature’ and the use of local resources, knowledge and expertise. These are further gender-sensitive because the technology is simple and user-friendly particularly for women who are the main group of beneficiaries as the domestic water managers. The traditional water supply science and technology in India continues to be in use in many places, thereby indicating its validity and viability even in the modern era. Further, given its various advantages, it offers everyone the possibility to enjoy their human right to water even in an era of stress on water resources in both quantitative and qualitative terms due to several climatic and non-climatic drivers. It is indeed amazing that even with rainfall as low as 182 mm, drinking water needs of the people can be met using simple technologies for harvesting the rain. However, despite the multifarious advantages, these traditional systems are being increasingly ignored and threatened with disuse and dilapidation, being replaced by modern forms that are external in origin and may not be necessarily adaptive to the local climatic and environmental contexts. In light of the significance and validity of the traditional systems, there is need to revive, restore and strengthen them if water sustainability as well as the human right to water of women, men and children are to be promoted in the modern era.