Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Urban Drinking Water Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 January, 2017

More than 91% of urban households in India are claimed to enjoy the privilege of access to safe drinking water according to the latest Census of 2011. But what kind of access do they enjoy? Over 13.7 million urban households are located in informal colonies or ‘slums’ where basic amenities are inadequate. More than 43% of these households do not possess a drinking water source at home and have to procure drinking water from outside. These outside sources may be public tapstands, group connections, tankers, community handpumps, public wells, or even valves and leakages in water mainlines that pass by close to these colonies. Sometimes the source may be unsafe, exposing women, men and children to risks of ill-health. In other instances, these may be very distant, forcing them to carry water in bulk over long distances, causing hardships and risks of physical injury. The supply timing may be irregular or odd, sometimes late in the night, further increasing the hardships. In colonies served by water tankers, several valuable productive hours may be lost by women and men awaiting their arrival because there exists no punctual routine. All this may lead to reduced incomes as well as disturbed routines at home even for children, who often assist in the task, in turn affecting their education. In many instances, the number of dependent households is large for a single supply point, while the supply duration is short. Further, the pressure in the tap may be too low. All this may often lead to rush and queues, scuffle and struggles, with some even forced to return empty-handed at the end. Even in the formal colonies, the existence of pipeline networks is no guarantee of a safe and secure drinking water supply. Good quality safe drinking water is a challenge in many metropolises and other cities and towns. In the hilly areas, urban water supply may be fed by seasonal springs and streams, causing water distress during the dry months. This photo story presents glimpses of the varied challenges facing urban communities in drinking water procurement in India despite the rosy coverage figures in official records. These challenges undoubtedly thwart enjoyment of the human right to water as well as other concomitant rights by the affected women, men and children. The title photo depicts residents of a posh colony in South-East District of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD) who are protesting for restoration of their human right to water after several days of disrupted water supply.

Procuring drinking water from a leaking pipeline in an informal colony in Mumbai, Maharashtra

In Mumbai - the business capital of India - about 9 million, which totals to over 60% of the city's population, lives in informal colonies (Census of India, 2011). In many of these colonies, access to drinking water presents formidable challenge as sources may be absent, inadequate, distant or provide irregular supply. In such situations, people are forced to explore even unconventional alternatives. The public standpoint in the informal settlement around the pipeline shown in this photo has too many users. Consequently, a number of residents prefer to collect water from leakage in this pipeline, inserting pipes into its joint as well as collecting the dropping water into pots directly. While the endeavor helps avoid rush and queue at the public standpoint, the adventure of climbing atop the pipeline as well as walking around to collect water from the leakage poses considerable risks of slipping, falling and getting injured, particularly because the area around is muddy and slippery.

Struggling to collect water from a pipeline leakage in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Delhi is one of the biggest metropolises in the world with a population of around 17 million, but nearly half its people live in slums and unauthorized colonies without adequate civic amenities. In this colony, very few have a drinking water source at home, while others have to depend upon leakage from a pipeline that passes close by but does not provide water to this colony. The people are collecting drinking water from this leakage after descending down a wastewater drain over which the pipeline passes, which itself raises serious health concerns. The water remains in the pipeline for a limited period and people have to rush for getting their share for the day, an exercise in which many women, men and children also slip and fall, getting injuries.

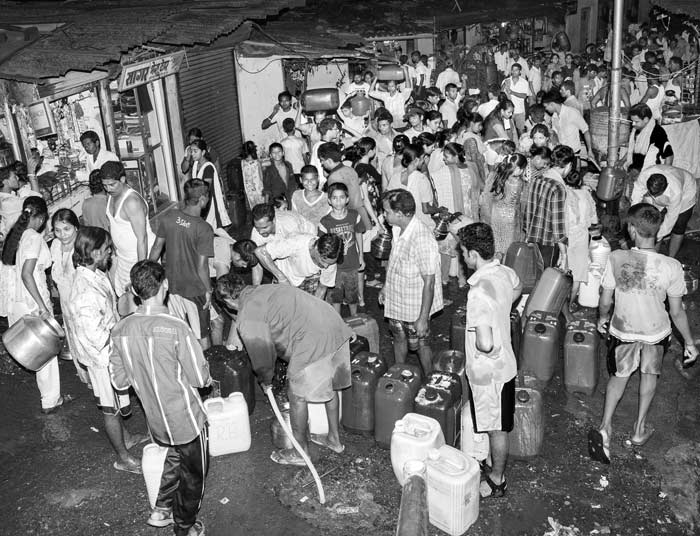

Queue and rush for water at a public tapstand in Anantpur city, Andhra Pradesh

In Anantpur city, a good proportion of the 31% population living in unauthorized settlements experience much struggle for fulfilling their basic drinking water needs. The duration of the water supply at public standpoints can be extremely limited, causing much hardship for the dependent populations. At this standpoint in an informal colony in the city, the supply timing is quite uncertain and the duration is limited. This forces people to arrive early, putting their containers in queue, and thereafter rush for their turn once water arrives. The uncertainty of the timing leads to useless waiting compromising other essential chores while the burden of carrying back water containers on a daily basis causes health strains and even greater loss of valuable time.

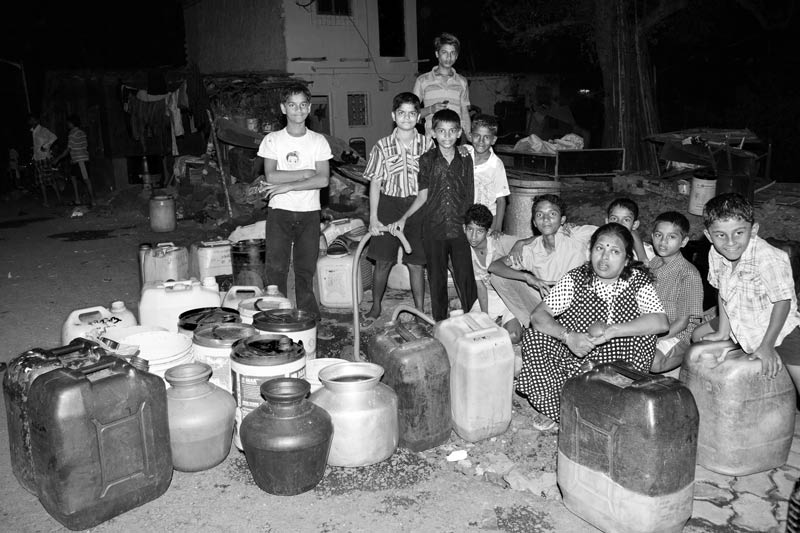

Waiting for water late in the night at a group connection in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Many informal colonies in Mumbai have ‘group connections’ from where all member households can collect water. However, water supply timings may be odd at these points and the exact hour may be quite uncertain. At this group connection, the expected time is around 10 in the night. This keeps women, men and children awake until late, and sometimes even after the prolonged wait, the taps may remain dry, thus making the entire effort a waste. This disturbs sleep, hampers children’s studies and affects daily domestic chores.

Struggling to procure drinking water late in the night at a group connection in Mumbai, Maharashtra

At the group connection in this photo, water has arrived around 10 pm. The men, women and children who have waited for long for water, scuttle to get their share. In the process, water may spill from the containers, making the place slippery, and in the darkness of the night, cause considerable risk of tripping, falling and getting hurt. In fact, the people narrate how several women and men have actually broken legs, arms and received serious injuries in this exercise. The process is also time-consuming, since the pressure is often low. Also, some of the users may end up deprived because there is too little water but too many takers.

Waiting for water tanker in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

In a number of unauthorized colonies in Delhi, drinking water needs are fulfilled through tankers. However, the tanker supply can be highly irregular. Though a water tanker is supposed to serve the colony shown in this photo every morning, the time is not really fixed, making men, women and children wait endlessly, wasting valuable productive time. Sometimes, the tanker misses its trip, causing great inconvenience. Since water is an essential resource, in such a situation the residents may be forced to buy drinking water or procure it from greater distances.

Struggle for collecting drinking water from a tanker in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

After a water tanker arrives, fetching a container of water is not an easy task. The quantity is limited but takers are numerous. In fact for being successful, it has to be a family effort since one person must climb atop the tanker and insert the pipe into it, another one must quickly fill the containers while a third one must quickly move away the filled ones. At the end, all of them must jointly carry the containers back home. In this struggle those who lack the requisite manpower are defeated and may have to return home empty-handed. The venture of fetching drinking water from the tanker is full of risks. Climbing on the tanker is risky as sometimes boys and men lose balance and fall. Moreover, the tankers mostly stop along busy motorable roads, posing the risk of accident, particularly afterwards when filled-in containers remain stranded in the middle of the road and are removed by the residents one by one amidst heavy traffic. In fact a number of such accidents are recalled by the public at this venue.

The private cable water supply maze in Kohima town, Nagaland

Kohima, the capital of Nagaland in north-eastern India is a picturesque town situated amidst lush green nature, but drinking water crisis is a formidable challenge for its residents. The Public Health Engineering Department (PHED), the main organization looking after water supply in Kohima, is able to cater water to only around 40% population; that too at a very low per capita rate. A large part of the remaining population get water from private cable water lines that generally supply spring water through thin plastic pipes criss-crossing the city in bunches. These pipes run very haphazardly along streets, across rooftops and on electrical and telephone posts, converting this beautiful town into a ghostly jungle of pipelines and cables. Despite this, not everyone can get water at home nor is cable water supply a permanent source. It is in fact a luxury that many cannot afford. If a cable supply pipeline is installed at home, the nonrefundable charge is around Rs. 4000 with a monthly bill of over Rs. 300, while from publicly located points, water collection charges are around Rs. 500 per 1000 liters. Moreover, supplies from the cable network, and also other alternate sources like springs and wells, become irregular, erratic and meagre during the lean months from January till June, causing much hardship.

Collecting drinking water from an open well in Mumbai, Maharashtra

The lack of sufficient water supply points in many informal settlements forces women as domestic water managers to procure drinking water from alternate sources. However, since groundwater salinity is a major problem in Mumbai, the availability of alternate sources like well and handpump is limited. Here women are seen to draw drinking water from a shallow well recharged primarily from the neighboring Powai Lake. However, while salinity is not a problem here, the quality of the well water is still questionable since it lacks a lining wall around, exposing it to direct drainage of polluted water and other waste from the surroundings which could contain microbial and chemical contaminants. Consumption of contaminated water exposes these women and their families to risks of water-borne diseases like diarrhea, typhoid, and hepatitis and other adverse health impacts from chemical residues.

Queueing up for drinking water at a public standpoint in Bengaluru, Karnataka

Nearly 1.4 million people live in over 1500 unauthorized colonies and slums in the rapidly expanding Bengaluru city. A regular, reliable and safe water supply is a major challenge for many residents in these informal settlements. Many of these settlements have been provided with public standpoints but the ratio of users per point is quite high and consequently, queue and rush at these standpoints is a common phenomenon. Also, as common in other urban areas, the water supply timings can be inconvenient and uncertain. At the standpoint shown in this photo, the supply timing is very early at 5.00 am which disturbs sleep, making women wake up even earlier to reserve their place in the queue. Some women prefer not to take a chance and wait until water arrives while others reserve their place in the long queue by leaving their water containers behind. At the end, carrying the multiple water containers home ends up as a cumbersome task on a daily basis, taking a heavy toll on physical well-being and productive time of the residents.

Returning with water loads in the dark from a distant source in Mumbai, Maharashtra

In some informal settlements in Mumbai, there may exist no regular drinking water sources. Residents of such colonies may have to travel long distances, even in the dark of the night as shown in this photo, to fetch water from another area. For women and girls, traversing long distances alone in the night may not be safe, while for everyone –women or men - hauling heavy water loads manually after a long working day may be tiring, bringing health hazards.

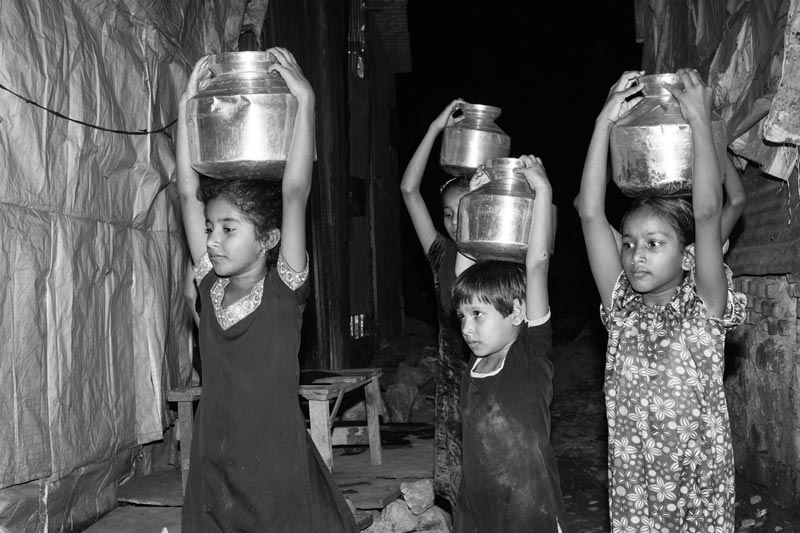

Girl children carrying headloads of water in the night in an unauthorized colony in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Drinking water is everyone's need at home, and its procurement therefore becomes a cooperative family effort in which even children must contribute. Irrespective of the supply hour, children of all ages and both genders, are often seen carrying water containers in urban areas. In this informal urban settlement, girls are bringing headloads of drinking water collected from a group connection late in the night. Carrying heavy headloads by children on a regular basis poses risks of cervical and spinal injury, retarded growth, and hampers their education and other developmental activities.

Serving drinking water from the stored weekly ration in a planned colony in Secunderabad, Telangana

Drinking water challenges are not confined to only the informal urban areas. In this planned part of the city of Secunderabad, drinking water supply is provided in the form of a weekly ration. The drinking water which comes through a separate pipeline only once a week has to be stored and consumed carefully so as to last the family throughout the week. If not hygienically stored and handled, the water can cause health distress and in the eventuality of being consumed before the next supply, it can add to financial burdens through the need to buy bottled water.

Procuring drinking water from a pipeline leakage in Dhanbad, Jharkhand

Dhanbad is the second most populated city in Jharkhand, famous for its coal mining and hence popularly called the ‘Coal Capital of India’. Drinking water crisis has been identified as a major urban risk in the city due to dwindling groundwater resources which affects water supply even in the planned parts of the city during the summer months. In the informally settled colonies, mostly on the city outskirts, the water supply crisis is even more perpetual since regular water supply sources are limited. Consequently, people may be forced to fetch drinking water from alternate sources such as the one shown in this photo. This pipeline carries water to the main city, but its leakage forms a pool from where people residing in the unsettled colony nearby procure water, though in an unclean setting and in an unhygienic manner which poses substantial health risks.

The virtual tour through the urban drinking water challenges in India throws up important questions for consideration. First, notwithstanding the high official ‘coverage’ figures, a substantial part of the urban Indian population continues to suffer from lack of access to adequate, regular, reliable, safe and affordable drinking water sources. This implies the inability of the affected women, men and children to enjoy their human right to water. Second, drinking water challenges are widespread in urban centers. While the worst affected are generally those residing in the informal colonies or slums, even residents of the settled colonies ‘covered’ by piped networks water within premises are not actually secured and may suffer in different ways. Third, these challenges are not only about drinking water, but their implications are actually far-fetched. Women, men as well as children in the affected households may suffer from physical injuries or ill-health due to regularly carrying heavy water loads over long distances or consuming unsafe drinking water. This in turn may increase household medical expenses. Significant amount of productive time may be lost by women and men in endlessly waiting for water and hauling drinking water loads back home everyday, in turn reducing family incomes. Girls and boys too may be engaged in these tasks, making them miss valuable study time as well as recreation opportunities, thwarting their proper growth and development. Further, where drinking water has to be purchased, additional financial burdens may accrue. All this thwarts enjoyment of the human rights to health, education, work and overall development. This is not the situation in a few isolated urban pockets - what is presented in this story is a mere selection. This is the scenario existing widely across urban India in diverse forms. India is rapidly moving towards greater urbanization but obviously without a secure access to adequate and safe drinking water for everyone, sustainable urban development and universal realization of the urban residents’ human right to water is not possible. There is thus an urgent need to recognize the existing bottlenecks, develop sustainable solutions and apply these equitably, so that the magical figure of 91% or even more can be realistically achieved.