Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water Leaders

Chattar Singh Jam: The Water Wizard of Thar Desert

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

23 August, 2018

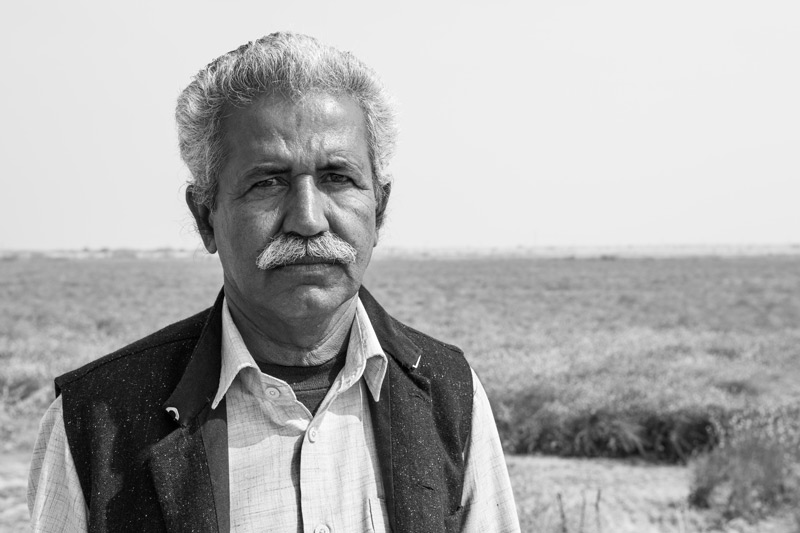

In the heart of the Thar Desert in Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan lies Ramgarh region where rainfall is scanty, the landscape is covered by dry desert soil and sand, and vast stretches are dotted with sparse scrub vegetation. Unbelievingly, in this water parched land, thrive villages which are islands of prosperity because these are self-sufficient in water. The wizard who has brought about this miracle is Chattar Singh Jam who holds expertise in water and ecosystems management in the desert, deriving from the traditional wisdom handed down by his forefathers. He has made relentless efforts in reviving the rapidly disappearing traditional knowledge which is rooted in the nature-based solution of rainwater harvesting, sensitizing communities for rejuvenating this science and helping them undertake collective action for conserving and sustainably managing their scarce water resources. He poses the question that no drought was reported in Ramgarh in 2014 when there was barely 11 mm monsoon rainfall, or in 2015 when it was 48 mm, or later in 2016 when the figure was again only 20 mm. Then how come areas of India receiving hundreds of mm rainfall are increasingly becoming drought-affected? He contends that the real cause of drought is lack of wisdom and not the scarcity of rain. For him, 'development' requires that the local community's knowledge, understanding and perspectives about nature and water should continue to guide its life activities in such a way that economic progress goes alongside ecological sustainability. Otherwise, poverty and under-development are unavoidable. Chattar Singh has helped several village communities in Ramgarh region undertake rejuvenation of their traditional rainwater harvesting structures, notably drinking water ponds (talab) and shallow wells (beri), and agricultural khadins which are fields that remain inundated with runoff for up to two months and then drained out to be sown with winter ('rabi') crops. As result of Chattar Singh's continuous efforts, today these villages are self-sufficient in drinking water. Women have access to drinking water not only round the year but have been ensured this access even through three or more consecutive drought years when the rainfall is so little that surface water bodies remain empty. They, their children and the menfolk have secure access to food through abundant production of wheat which is saved for domestic consumption and cash crops like mustard and gram that are sold in the market to buy food and other essentials. Moreover, animals have enough water to drink and fodder from the field to last even through the dry months, which has boosted animal husbandry. This photo story showcases water wizard Chattar Singh's work for sustainable development through sustainable water resources management in the Thar Desert. It presents glimpses of the different kinds of rainwater harvesting structures based on traditional water wisdom that he has helped rejuvenate or newly create in the Ramgarh region together with the local village communities. The title photo portrays Chattar Singh at the banks of a khadin named Bijrasar that he has rejuvenated during the last three years, with support from some well-wishers and fellow villagers.

The landscape of Thar Desert in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Water, or the lack of it, defines the Thar Desert. In Jaisalmer district, which lies at the heart of this mighty Desert, major rainfall is received at the tail end of the monsoon season, with some winter showers also brought in by the western disturbances, yielding an annual precipitation ranging between 100-400 mm. During summers, daytime temperatures are high - often above 45°C, evaporation levels are high and groundwater recharge is low, making this a water deficient region. Many parts of the district are covered with desert soil and sand, with rolling sand dunes in some pockets as shown in the photo above. Ramgarh region lies in the western part of the district, encompassing about 60 villages lying within approximately 50 km radius from Ramgarh village, which was once a sub-district (Tehsil) headquarter in the district. This is the driest part of Jaisalmer district and India where average annual rainfall is as low as 100 mm. Natural surface water bodies are next to absent and the groundwater is deep and saline. The vegetation is sparse here, with some grasses, xerophytic plants and limited trees. In this dry and hot desert region, Chattar Singh has wielded the magic of restoring waterscapes and ecosystems, making villages self-sufficient in water.

The 'water wizard' of Thar Desert - Chattar Singh Jam

Chattar Singh Jam, aged 57 years, is a resident of Ramgarh village in Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan. He has spent his childhood and youth practicing traditional water resources management under the guidance of his parents and grandparents, learning the treasured wisdom of carefully conserving and sparingly using each and every drop of the scarce rainwater received on the land of Ramgarh. He cherishes rich memories of how he learnt the art of managing khadins and cultivating 'rabi' crops in them and of creating and maintaining the small drinking water wells ('beris'). During the decades of 80s and 90s he came to be engaged in a number of water-related works implemented by the government and was later drawn into participatory ecosystem-based water conservation work with the non-governmental organization Sambhaav during the period 2006-2014. Since 2014, he has been working at his own initiative, partnering together with local communities, friends, well-wishers and supporters, to carry forward the mission of achieving sustainable development in the Thar through nature-based solutions for water.

A rejuvenated drinking water pond called Viprasar on the outskirts of village Netsi

One of the initiatives of Chattar Singh has been repair and rejuvenation of village ponds. Through Sambhaav, he has helped restoration of 3 large and 3 small ponds, which are in use as drinking water sources by local communities for themselves or their animals. Viprasar, is a large pond located on the outskirts of a village called Netsi. This pond gets filled-up with runoff resulting from a rainfall as little as 30-50 mm, collected from a catchment of about 25-30 km. This greatly facilitates village women and girls who procure 'sweet' drinking water from the pond, as shown in the photo above. Once every 2-3 years, Viprasar gets filled and the surface water remains available for a period up to one year. The pond was created about 300 years ago as a source of 'sweet' drinking water in the area and is historically a joint resource of 12 contiguous villages. With financial support from Sambhaav, Chattar Singh has helped rejuvenate this large pond by repairing its embankment and deepening its base through community participation. At present, almost all the 168 households of village Netsi are dependent upon 'sweet' drinking water from Viprasar during the years it gets filled. The community has developed social rules regarding management of Viprasar particularly to ensure maintenance of the water quality.

A rejuvenated shallow drinking water well - ‘beri’- in Viprasar bed

Another important initiative of Chattar Singh has been rejuvenation of shallow drinking water wells called ‘beri’ which generally lie in clusters called ‘taanda’ in or near surface water bodies like ponds and khadins. With Sambhaav’s support, he has successfully enabled rejuvenation of 100 traditional beris in Ramgarh region. These include 24 beris (out of a total 120 original ones) in Viprasar, which is not only a drinking water pond, but also serves as a taanda during the dry months. The beris in Viprasar have been deepened up to approx. 8-10 m and stone walls created around each to make them safer and more robust, one of which is shown in the photo above. 100 new beris have also been dug in the region, which facilitates women with greater access to ‘sweet’ water even under drier regimes.

Chattar Singh exploring the water table in a ‘beri’ in Viprasar

High water table inside a 'beri' in Viprasar

The importance of Chattar Singh's work with beri rejuvenation emerges from the fact that village women are never short of drinking water because beris in the villages where he has worked never dry up, even through consecutive droughts. During the rainy season, these get recharged and initially water becomes available at a depth of barely half a meter, as shown in the photo above. Though with progressive water abstraction, the table deepens but even at the end of the dry season, women can procure water from a depth of just 3-3.5 m. During those years when rainfall is scanty, the runoff is not enough to fill-up surface water bodies but the beris still get recharged, serving as an insurance to drought. In fact, in the case of Viprasar beris, the recharge is so efficient that water remains available for fulfilling the drinking water needs of village Netsi even if three consecutive years turn out to be 'drought years', with just 10-20 mm rainfall. During such periods, even neighboring village communities get a share in the water from Viprasar beris.

Rejuvenated beris in the bed of a seasonal rivulet in Hema village

Hema is a small village close to Netsi. Since the village did not have a local source, women and girls of Hema had to walk down to Viprasar for procuring drinking water. This problem was solved by Chattar Singh by helping restore local drinking water sources in the village. With support from Sambhaav, he helped the community rejuvenate four beris that are situated in the bed of a monsoon rivulet that flows for just a couple of days during the rainy season. These rejuvenated beris are shown in the photo above. The rivulet which helps recharge the beris originates at a pond called Jiyadesar located on the other side of the village. This pond has been deepened at Chattar Singh’s initiative, so that larger runoff volume can feed the rivulet. After the rains, water becomes available in the beris at a depth of about just half a meter.

Women procuring water from a rejuvenated beri in the bed of a rivulet in village Hema

The beris rejuvenated in Hema are not used all at once. Women use them one after the other, so that the ‘sweet’ water available in them is able to last the community for one whole year. These get recharged again during the next monsoon, even if the rainfall is scanty. One of the rejuvenated beris being used by women of Hema is shown in the photo above.

Livestock drinking water at a ‘kheli’ during the dry season

Even the livestock has been facilitated by Chattar Singh’s rainwater harvesting interventions. Every rejuvenated beri has a shallow tank attached to it into which water from the beri can be poured for the livestock. This tank is called ‘kheli’ and animals are able to conveniently drink water here during the dry season when surface water ponds start disappearing. The large livestock population of more than 16,000 in Netsi village, comprising of sheep, goat, cattle and camel, is highly dependent on these khelis, one of which is shown in the photo above.

A rejuvenated deep well called ‘Patali Kuan’

Apart from paying attention to the sweet water shallow wells (beris), Chattar Singh has also been engaged in rejuvenation of deep wells which are called ‘Patali kuan’ in the local parlance. Five deep wells have been rejuvenated by him with support from Sambhaav, one of which is shown in the photo above. This is located in a distant habitation of village Netsi called Maithitala which is located about 25 kms away. The water table here, as shown in the photo above, is very deep - about 65 m - and the water is saline. However, since there is no other source of water here, the well is used for all kinds of purposes – potable and non-potable. Water is drawn from the great depth in large containers having capacity of about 80 liters with the help of camels, and for storing this large quantity of water, Chattar Singh has helped with construction of two tanks next to the well. One of these, locally called ‘kapuriya’, stores water for human consumption, from where women procure water. The other one, called ‘Kotha’, stores water for the livestock from where it is transferred to an adjacent kheli to facilitate drinking by the animals. Maithitala is inhabited by about 15 families that specialize in animal husbandry.

Derasar khadin inundated with runoff from its catchment

Another important nature-based solution for water to be rejuvenated by Chattar Singh is the khadin. 'Khadin' is an age-old land use system of run-off agriculture in Jaisalmer district in general and Ramgarh region in particular, wherein the runoff from adjoining rocky or gravelly catchments is impounded on low lying farmlands for subsequent winter (rabi) cropping. Chattar Singh says that after the coming of the Indira Gandhi canal (IGC) in the region, bringing the promise of irrigated agriculture, farmers in local communities began neglecting this traditional practice. In Ramgarh region, there existed about 100 traditional khadins, many of which gradually fell out of use by the turn of the last century. Meanwhile, the IGC failed to deliver adequate and regular irrigation water, resulting in downfall of agriculture, in turn weighing heavily on the socio-economic wellbeing of the villages. Since in many villages, drinking water sources (beris) also depend upon khadins for recharge, access to sweet drinking water became a challenge too. Chattar Singh sensitized communities about the significance of khadins and with their participation, helped rejuvenate three large khadins, each covering 75-100 hectares area. The above photo shows one of these – called Derasar – fully inundated with just about 48 mm of monsoon rains. About 50 new khadins, each measuring 5-10 hectares have also been created under Chattar Singh’s guidance. On the whole, his efforts have brought over 1000 hectares of khadin land under cultivation in the region.

Chattar Singh explaining about 'Goedhan' in Derasar khadin

Every khadin has a pillar called goedhan which is used for measuring the water level during inundation. In the above photo, Chattar Singh is indicating the comparative water levels achieved during the previous monsoon periods.

Chattar Singh explaining about the structure and restoration work undertaken at Derasar khadin

Derasar is a large ‘communal’ khadin owned jointly by three villages – namely, Raghwa, Seuwa and Joga, extending over an area of 75 hectares, which came to be neglected after the coming of IGC and remained out of use for several years. A khadin has catchment on three sides and an embankment on the fourth side to impound the runoff. Spillways on the sides of the embankment allow excess water to drain off. The embankment can be earthen or even cemented. In case of 500 years old Derasar, the embankment is made of limestone. Chattar Singh initiated repair of the embankment and associated structure at Derasar with support from Sambhaav, as is being explained by him in the photo above. The rejuvenated Derasar remains flooded for about two months and during early September, the water is drained out through a small opening at the bottom of the embankment. In September 2017, the water from Derasar was sold out to farmers downstream for 100,000 Indian Rupees (approx. 1,430 USD) who further used it to inundate their individual fields for shorter periods, which were thereafter sown with rabi crops. This money is used for maintenance of the khadin.

Chattar Singh inspecting gram crop (chana) cultivated in Derasar khadin

Chattar Singh’s efforts at khadin rejuvenation have born fruits. He explains that the khadin is a collaborative effort between nature and human beings. Every year the area under submergence in the khadin, and hence the cultivable area, increases as silt brought together with the inflowing water settles down. Simultaneously the fertility of the khadin soil increases as new silt carrying nutrients comes in. Chattar Singh claims that khadin is able to yield three crops over a period of five years, while production with IGC irrigation is uncertain due to irregularity of the water supply. The khadins are sown with wheat, mustard or gram, depending upon the nature of the catchment and hence fineness of the soil. At present the average production is 10 quintals per hectare, which means a total production of more than 10,000 quintals of different kinds of crops in the 1000 hectares of khadin land that he has helped rejuvenate or create. During the 2017-2018 rabi cropping cycle, Derasar was used for growing gram, as shown in the photo above.

Close-up of gram crop (chana) in Derasar khadin

A view of inundated Bijrasar khadin

Even after the period of his engagement with Sambhaav, Chattar Singh continues to remain engaged in rejuvenation of traditional khadins. Over the last three years, he has initiated rejuvenation of four large communal khadins, namely, Bijrasar, Saran, Barala and Bakarthala. Of these, he holds a share in Bijrasar, shown in the photo above, which is a communal khadin of 12 villages, including his own village Ramgarh. Bijrasar, spread over an area of about 80 hectares, had been lying neglected for 18 years. As a result, its embankment was broken, and the fields came to be infested by Vilayati Babool (Prosopis juliflora). With financial support from friends and well-wishers and help from some like-minded individuals from the village, Chattar Singh got the embankment repaired and most of the babool infestation cleared off. So far, the khadin has come to be flooded after monsoon rains twice - in 2015 and 2017, yielding rich rabi crops. The outflow of water at the end of the inundation period was further used to inundate individual fields in an area of 60 hectares downstream. Ironically, this area lies within the IGC irrigated belt but has no water.

Mustard crop in Bijrasar khadin

During the rabi season of 2015-2016, about 50 hectares in Bijrasar which was restored came to be sown with mustard, leading to a yield of 500 quintals. In 2017-2018, all the 80 hectares in this khadin was sown with mustard, a glimpse of which is presented in the photo above. The production from this khadin has been 800 quintals, generating an income of 2,800,000 Indian Rupees (more than 40,000 USD). The total income from the wheat, gram and mustard crops cultivated in all the khadins rejuvenated or newly created at Chattar Singh’s initiative has been about 50 million Indian Rupees (approx. 715,000 USD) during the 2017-2018 rabi cropping cycle.

Chattar Singh amidst matured mustard crop sown in Bijrasar khadin

Wheat crop in Tanosar khadin

In khadins having the finest quality of soil, where moisture is retained more efficinetly, wheat is sown. Wheat grown in khadins has a special flavor because it is grown completely ‘organic’, without fertilizers and pesticides, and therefore fetches thrice the price in the market. However, in Ramgarh region wheat is mainly produced for domestic consumption and is stocked at home to tide over food crisis during drought years. Tanosar in village Paarevar, has been rejuvenated by Chattar Singh with support from Sambhaav and is used for growing wheat, as shown in the photo above.

An irrigation pond being developed by Chattar Singh near Bijrasar khadin

In recent years, Chattar Singh has been involved in developing innovative nature-based solutions to improve agricultural yield from khadins. One of the limitations that often affects productivity is lack of winter showers during the rabi cropping cycle. Irrigation ponds are seen by him as a solution to this problem towards which he is in the process of developing the first pond near Bijrasar through coordination with a government department that was involved in digging up the surface rocks nearby. This pond has a depth of about two metres and got recharged with the runoff during the first monsoon it received in 2017. The water so collected was used to irrigate the mustard crop in Bijrasar in mid-cycle using sprinklers and led to increase of yield by up to 6 quintals per hectare. Chattar Singh plans to popularize this innovation further.

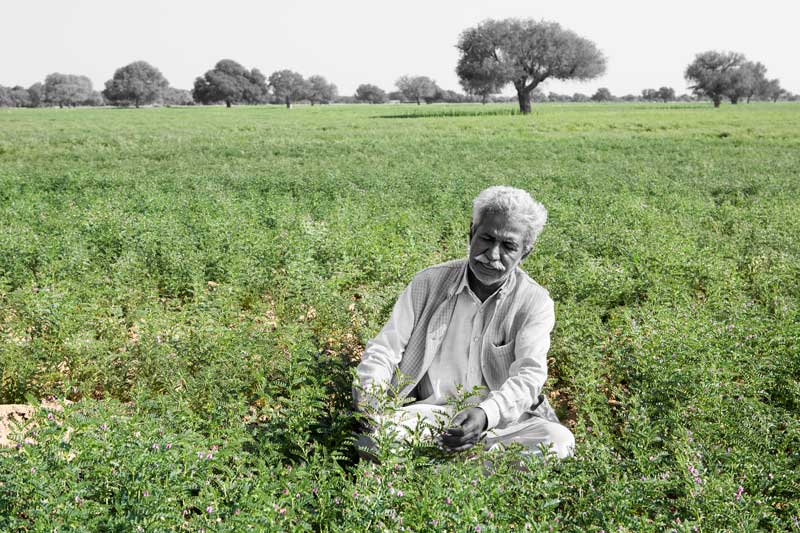

A Bhil farmer standing amidst gram crop growing in his khadin

Chattar Singh has also attempted to benefit the socio-economically backward groups in the region. One such group are the Bhil tribe who have traditionally been animal herders, also working as manual laborer, besides practicing limited rainfed kharif (summer) cropping. Due to shortage of water in their villages, Bhils have historically practiced transhumance, migrating with their flocks in search of pasture and water during the dry season. In order to help them with better livelihood, Chattar Singh guided them to develop 35 small khadins in their fields in a series. One of the first farmers to be benefited by this initiative is Gaji Ram, shown in the above photo. He owns about 12 hectares of khadin land on which he has been practicing agriculture for the last 8 years. The land was allotted by government in 1972, but due to lack of water, these fields lay fallow. With Chattar Singh’s efforts and small investment from Sambhaav, embankments were created on Gaji Ram’s and other farmers’ lands, leading to creation of fertile khadins over 150 hectares in Bhil villages like Ekalpar and Dabbla Paar. In 2017-18, Gaji Ram could produce gram crop worth 400,000 Indian Rupees (approx. 5700 USD). He also owns 160 livestock and produces some rainfed kharif crops on another field. As a result of these interventions, the Bhil tribal communities have been able to change from nomadic to settled lifestyle and their living standards have improved drastically.

The wonders brought about by Chattar Singh in the water-parched desert land of Ramgarh offers many lessons for the larger world. As the story illustrates, he has adopted a nature-based approach, clinging to the age-old traditional science of rainwater harvesting. Through simple local technologies he has enabled communities to catch every drop of the scanty rain that falls in Ramgarh region, utilizing it for multi-dimensional societal development. Through his initiatives, both drinking water and livelihood challenges have been addressed, and even the poorest and weakest sections of society have benefited tremendously. He has truly demonstrated how nature-based solutions are integrated, bringing nature and communities together, helping the latter grow and develop sustainably. The drudgery of women resulting from the need to carry water over long distances no longer holds true in the villages where Chattar Singh has initiated action. ‘Sweet’ potable water is available in close proximity of the settlements near or inside ponds and khadins, sharply contrasting with some other villages in the district where piped water in the heart of the village has brought disease and discomfort due to salinity, fluoride or supply of unclean surface water. Moreover, even the engineering feat of the IGC which was constructed to bring irrigation water and hence greenery to the Thar has failed its promise in Ramgarh region mainly due to reduced water flows over such long distances. On the contrary, Chattar Singh’s local nature-based solution of rainwater harvesting has shown the potential of yielding larger water volumes and greater productivity with every passing monsoon. Moreover, while increasing desertification of cultivable land is emerging as a huge problem elsewhere in India, Chattar Singh's intervention on the contrary is leading to shrinkage of already existing desert areas, progressively turning them into fertile cultivable fields. The system further offers the benefit of climate-proofing against floods and drought in the desert as the speed of the run-off gets checked, it is allowed cascading space to settle down and its storage under-the-ground produces long-term water treasure. Even food security for humans and livestock is ensured through the agriculture it supports. In terms of human rights, it is evident that Chattar Singh’s initiatives have helped secure the human right to water for women, men and children, as also their right to good health, sufficient food, and profitable livelihoods. From the perspective of sustainable development, it definitely brings together integrated development considering the social, economic and ecological dimensions, supporting several of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It is high time that the power of nature-based solutions for water be recognized and the model set by Chattar Singh be adopted far and wide across rest of Jaisalmer district, the state of Rajasthan and several other parts of India where, irrespective of the quantum of rainfall, water scarcity or even drought have become commonplace.