Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water Leaders

Jaya Devi: The Water Lady

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

21 May, 2016

Jaya Devi is a water crusader who has been working relentlessly for more than a decade to bring water in the resource-poor water-stressed region of Dharhara Kol in Munger district, Bihar, India. This is a rain-shadow area which receives a rainfall of the order 700-800 mm annually, but due to the hilly undulating topography, the runoff quickly disappears downstream. As a result, until recently the region used to be characterized by bare hill slopes, barren uncultivated lands, and a low water table especially during the summer months when even drinking water became a challenge. The region is populated by socio-economically backward sections, including scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, who were subject to large-scale poverty since the yield from rainfed agriculture – the main source of livelihood - was often low. This in turn led them into the clutches of local moneylenders, further deepening their poverty and causing migration. Having experienced poverty herself as a member of a scheduled caste, and after having attempted to improve the socio-economic condition of her community through the 'self-help group' movement, Jaya Devi realized that the real cause of their plight was the perpetual water stress facing the region. So, she set out to solve the problem by augmenting the local water resources through watershed management. In this endeavor, she came in contact with Kishore Jaiswal, an experienced watershed development professional, activist and community organizer, who has continuously motivated, inspired and guided Jaya Devi in her efforts. With his support, Jaya Devi initiated watershed activities together with her community members – the women and men who were already organized into self-help groups. With financial support from the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), watershed projects were implemented through various facilitating agencies, starting in 2006. The first was Kareli watershed where her own village Saradhi is located, and soon extended to five other watersheds. Based on rainwater harvesting and water conservation practices, these efforts have delivered unbelievable results, leading to effective water resources management that enhanced 'blue water' storage on the surface and 'green water' retention in the soil. This made hillslopes turn green, agricultural production boost several times, and added new livelihood options such as vegetable cropping, fishing and cash income through participation in watershed activities. Drinking water is no longer a problem even in dry summers and water table in the irrigation wells is always high. As a result, 9000 families living in the six watersheds have benefited immensely, and more than 5000 hectares of barren land turned into green belt. With incomes growing, self-sufficiency was evident, and the villagers succeeded in freeing themselves from the moneylenders' clutches. Today there is prosperity all around, for which Jaya Devi's relentless efforts have been recognized, bringing many awards and accolades nationally as well as internationally. In recognition of her efforts at bringing greenery in the barren Dharhara Kol region, she is also known as the 'Green Lady of Bihar'. This photo story presents the inspiring journey undertaken by Jaya Devi in transforming her area from a state of water poverty to water prosperity. The title photo is of Jaya Devi with the 'Real Heroes' award conferred by CNN, IBN and Reliance Foundation for the year 2012 in the environment section.

The key to Jaya Devi’s success in bringing water in Dharhara Kol region through watershed management lies in community participation. She has untiringly motivated and organized the women and men in the various watershed villages into self-help groups and village watershed committees to work together to create the watershed structures that help enhance the water reserves in the area. Jaya Devi is the Chairman of the Kareli Village Watershed Committee.

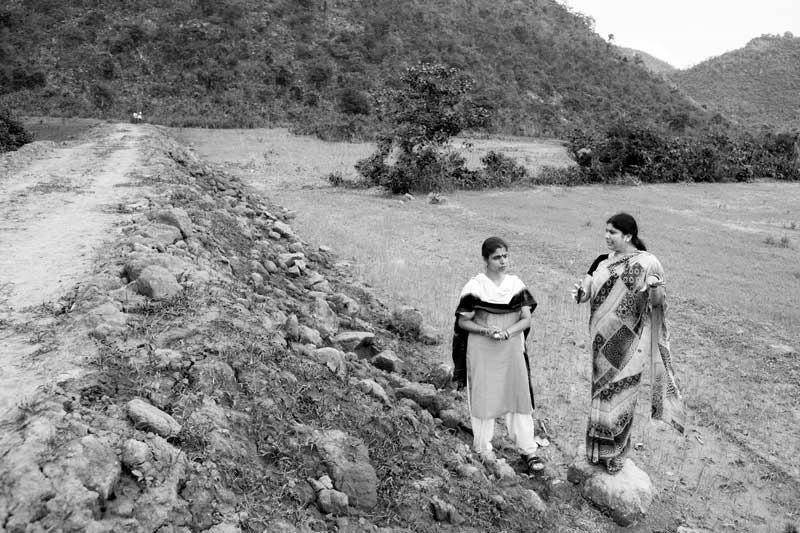

Jaya Devi explaining to Nandita Singh, a scientist from the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden about the checkdam being constructed across Kareli Nala through community participation. This is the main water channel carrying the runoff from the hills and flowing through 3 villages in Kareli watershed – Kareli, Khopapar and Saradhi. The water from the checkdam would make an area of 1000 hectares cultivable downstream, producing pulses like arhar (locally called ‘rahari’) and wheat, as well as oilseeds like sarson. Presently, these fields either remain barren or are used for dry cultivation of an inferior quality pulse called ‘kurthi’ which is eaten by animals.

A watershed structure called ‘gabion’ which consists of stones set in an iron net which is placed across the channel that brings the runoff from the hills. It acts like a checkdam, stopping and checking the water current. The excess water flows over the gabion further downstream while rest of the water remains nearby. This serves a dual function: helping water percolation into aquifers below thereby recharging groundwater, and increasing the soil moisture, facilitating agriculture.

A water channel in Kareli watershed created through community participation under Jaya Devi’s leadership. This channel brings water from the hills as well as the checkdam to feed the nearby ‘ahars’ which are water reservoirs enclosed from three sides with an opening on the fourth side through which water enters.

Karim Ahar in Kareli waterhed is the first ahar where Jaya Devi started the watershed project together with the community. 296 families contributed labor (shramdaan) in this ahar for its rejuvenation which helped rainwater stay in the pond. That year rains were initially good but suddenly stopped at the time of paddy transplantation. However, due to the water in the pond, farmers were able to raise good paddy crops. This success motivated everyone to undertake more watershed activities such as farm bunding, afforestation, trench digging, and plantation of fruit trees like mango and guava on farm bunds. Water stays in this pond until March-April, and if intermittent rains occur, then the pond does not dry up at all. This pond is also used for fishing under the leadership of the village watershed committee.

Puranki Ahar in Kareli watershed which earlier used to get recharged from the diffuse runoff coming down the hills nearby. The ahar would now be recharged with water from the checkdam across Kareli Nala brought through the newly constructed water channel. This ahar is also being rejuvenated under the watershed project since it is unable to retain the water it receives. All ahars are made on farmer’s individual lands because government’s land is very little in this watershed. Generally 4-6 farmers’ lands go into one ahar. If the farmers do not agree at once to contribute their land, they are convinced by the village watershed committee for the general well-being of the village as well as individual benefits, including for example exclusive rights to the profit from pisciculture in the ahar as well as to the fruits from the trees planted around it.

A ‘water absorption trench’ in Koilu watershed which is constructed at the base of the hill. The water flowing rapidly down the hill slope gets filled in these trenches and then overflows into a checkdam constructed downstream. The trench helps reduce the speed of the flowing water, thereby helping reduce soil erosion in the fields downstream. This also helps retain moisture in the fields as water slowly percolates from the trench through to the fields.

A checkdam in Koilu watershed which has been constructed through community participation along the slope of the hill to hold the runoff. To increase the volume of water in the dam, the base of the reservoir has been deepened and the soil extracted has been used to strengthen the dam. From one side the excess water is allowed to flow through an opening from which the water goes through the fields downstream, finally into an ahar.

As a result of watershed activities, soil moisture and groundwater reserves have been augmented. This has brought greenery on the bare hillslopes and in the surrounding barren lands.

Watershed interventions have led to increase of water table in the area, resulting in recharge of handpumps and drinking water wells. As a result, drinking water is no longer a challenge, even during the summer months.

Irrigation wells remain sufficiently recharged throughout the year, with considerably high water table. This has not only enhanced availability of water for irrigation, but even reduction in the volume of the water extracted, since now the moisture level in the soil is high.

Watershed management has boosted agricultural production and also increased the land area under cultivation. Earlier agriculture was possible only in fields with depression inside called ‘kyaris’ while stony ‘bhita’ lands used to remain barren. But now agriculture is possible even in 'bhita' lands due to retention of soil moisture and increased water availability. Watershed management also boosted the cultivation of paddy in the 'kharif' (monsoon) season through field bunding which helps hold water in the agricultural field, which would otherwise flow out. In case of delayed and inadequate rainfall, water from ahars and agricultural wells comes as rescue.

A view of mature paddy crop in one of the watershed areas.

A view of a ripened wheat field. Watershed management has increased water availability, thereby supporting cultivation of 'rabi' (winter) crop, such as wheat, gram and mustard. This is possible due to increased soil moisture as well as irrigation from the recharged wells.

A view of gram crop ('chana') in one of the watershed areas.

Jaya Devi was conferred the National Youth Award for 2008-2009 by the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India, for her outstanding contribution to national development and community service through voluntary participation.

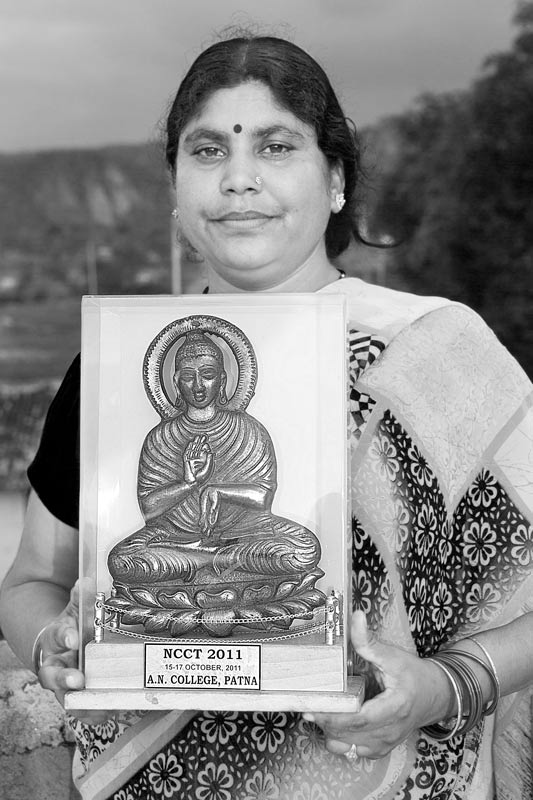

Apart from the awards mentioned earlier, Jaya Devi's efforts at community development through watershed management has been also recognized from several other quarters. She was conferred the Grassroots Women of the Decade Achievers award in 2014 by the ALL Ladies League, New Delhi, and the Rotary International Woman of Substance award by Rotary International Club, Mumbai in the same year. In 2013 she was awarded the Krishi Prerna Puraskar by Mahindra and Mahindra Foundation and in 2012, she received the Innovative Farmer of the year award from the Bihar Agriculture University, Sapour. In 2009 she received the prestigious Fellowship from Jamsetji Tata National Virtual Academy. In 2012 she was invited to deliver lecture on 'farm women's income enhancement' at the National Conference of Krishi Vikas Kendras of the Nation, organized by Punjab Agriculture University, Ludhiana. She was a Guest of Honor at National Chemistry Conference organized by A.N. College, Patna n 2011. In 2010, she was selected by the Government of South Korea to attend the Fourth Asian Youth Workers' training program at Cheonan, South Korea.

Jaya Devi’s journey for achieving community development through effective water resources management would not have been possible without the support of Kishore Jaiswal who has throughout been her Guru, mentor and guide in this endeavor. As a watershed development professional, he has been her ‘’guru’ helping her develop the capacities through necessary knowledge and skills for practicing watershed management. As a community organizer, he has been a constant source of inspiration and persuasion, encouraging her to organize and lead the community in undertaking watershed activities as a continuous process. Initially, Jaya Devi was herself hesitant, and lacked confidence that she will be able to organize the community and engage them adequately and appropriately. However, under continued support from Kishore Jaiswal, Jaya Devi was able to overcome the initial reservations and slowly convince the women and men in the community about the benefits and inculcate the necessary skills in them to the extent that today the village watershed committees are independent, self-motivated and active groups. These even attempt to design their own watershed plans, thereby minimizing the dependence on external engineers. This has led to a wave of change where the socio-economic status of the village communities living in the six watershed areas stands transformed. From a state of water poverty, the communities have become water prosperous, in turn enhancing food security and self-reliance.