Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and CultureA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2021

Art and Architectural Excellence at Rajsamand Lake, Rajasthan

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

17 September, 2021

The connection of water with art and architecture is multi-facetted, and among the finest manifestations is the creation of art and architectural forms at the site of water bodies. Art is a form of expression and creativity that may serve to enhance the beauty of the water body itself as well as create a locale that reflects cultural perceptions and forms. Architecture helps provide a structure to the water body and enables the creation of a unique physical environment, inspiring people to carry out various cultural activities at the location. Further, the art and architectural finesse connected with water bodies often thrive beyond the lives of the generations that create them, leaving behind a legacy to cherish. The arid and semi-arid state of Rajasthan is a place where water has always been ascribed a high value and several water bodies have been artificially constructed to conserve this precious resource, enabling survival of society. A number of these are well-known for their art and architectural grandeur, of which perhaps the foremost is Rajsamand Lake and its ornamental embankment, situated in Rajsamand district, about 66 km north of Udaipur. Also known as 'Rajsamudra', the lake lies next to the district headquarter town, known by the same name Rajsamand. It was created almost 350 years ago by Maharana Raj Singh I – a descendant of Maharana Pratap ruling the Mewar kingdom. One of the largest artificial lakes of medieval period, with dimensions of 6.4 km length, 2.8 km width, and over 18 m depth, it is renowned for its natural as well as artistic and architectural beauty. Given its expanse, this lake was used as a seaplane base by Imperial Airways during World War II. Mewar region is drought-prone, with an average annual rainfall of just about 568 mm. Therefore, the purpose of construction of this lake was to enhance the local adaptive capacity. The lake was created by constructing an embankment across Gomati, Kelwa and Tali rivers, with Gomati contributing the major water share. The catchment area is known to measure about 510 sq.km. This photo story elaborates the exquisiteness of the art and architecture at Rajsamand Lake's embankment. As evident from the title photo, the calm and scenic environment at Rajsamand Lake is enhanced manifold by presence of the ornamental embankment on it. The embankment, made of white marble, is big and robust, measuring 183 metres in length and 12 metres in height. The specialty of this embankment is 'nauchowki', nine platforms and nine stairs, each stair nine inches in height. Thus, number nine represents a fundamental principle cutting across all the art and architectural forms and structures at the embankment. This is inspired by Indian metaphysics and Hindu philosophy where number nine is considered auspicious, spiritually important and denote the Supreme Being.

Statue of Maharana Raj Singh I - the creator of Rajsamand Lake

Rajsamand Lake was constructed in the 17th century under the orders of Maharana Raj Singh I, the ruler of Mewar kingdom. He is known as an able ruler who built several lakes, ponds and step wells for public welfare. The idea of Rajsamand Lake emerged following a severe drought in the region in 1661, its construction implemented primarily as a famine relief work during the period 1662-76. Engaging a workforce of sixty thousand, the project was headed by Mukund Jagatnath as the chief architect. The project is defined as the oldest known relief work in Rajasthan and is estimated to have costed then more than Rs. 10,500,000. The rationale leading to construction of the lake was three-fold: providing immediate employment opportunities to the drought victims, creating extra water reserves to help tide over future droughts through rainwater harvesting during the normal rainfall years, and providing irrigation water to local farmers.

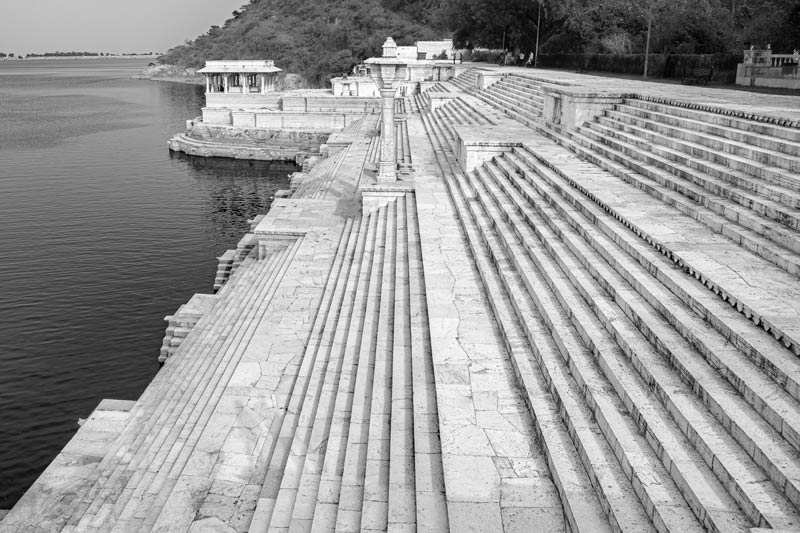

The embankment at Rajsamand Lake showing the 'nauchowki' – a series of nine flights of stairs leading down to the water

The most prominent architectural feature on the embankment at Rajsamand Lake is the 'nauchowki' - flights of stairs at nine subsequent levels across its length. Of these, the first four flights, seen in the above photo, run horizontally along the entire length of the embankment. The remaining five levels comprise twin flights of stairs shorter in length, placed perpendicular to the former. Each flight comprises nine stairs, each stair being nine inches in height. According to one legend, the art and architecture at the Rajsamand embankment was commissioned by Queen Charumati, in gratitude to Maharana Raj Singh I, who married her to prevent her marriage to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

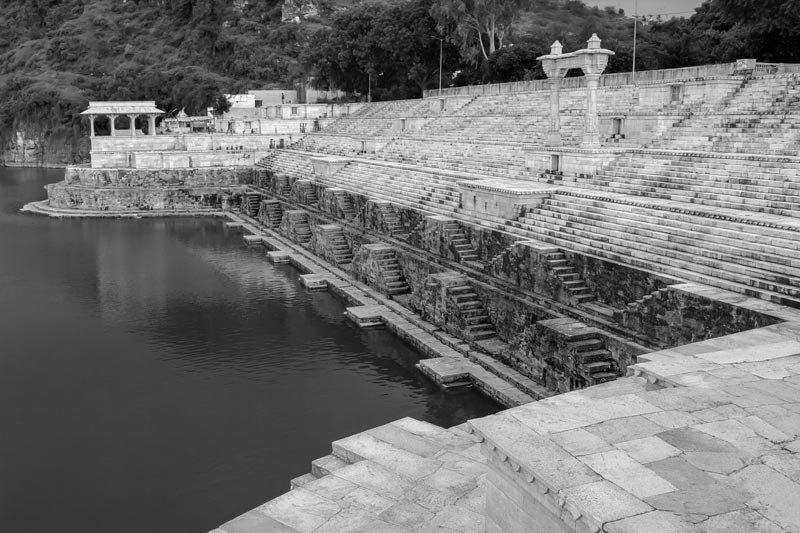

A view of 'nauchowki' at Rajsamand Lake, depicting six out of the nine levels of staircases

Out of the nine levels of staircases at Nauchowki, four are generally seen above water, except in some years when the water level in the lake becomes very high due to heavy rainfall in the catchment. The fifth and sixth ones emerge when the water level in the lake starts receding, as seen in the photo above. The seventh one generally remains under water and becomes visible only when water in the lake becomes scanty. The eighth and ninth ones are now covered under rubble and don't become visible even after complete drying of the lakebed.

A series of three large platforms ('chabutara') ending in a pavilion ('mandap') having beautiful carvings on the embankment of Rajsamand Lake

Another significant feature of the art and architecture on Rajsamand embankment comprises the series of marble platforms ('chabutara') which are of two sizes. The larger platforms are arranged in a series of three, with a pavilion ('mandap') situated at the end of the lowest platform. There are three such series along the length of the embankment, making a total of nine large platforms on the embankment. One of the three series is shown in the photo above. The smaller platforms are arranged in series of four. The larger and smaller platforms at the topmost level are decorated with beautiful carvings of different sizes, including series of tiny figurines depicting various avatars and Puranic scenes. These platforms are also known for housing the biggest stone inscription in India – 'Raj-Prashasti' - written by Ranchor Bhatt. Describing the history of Mewar and details about construction of Rajsamand lake, the epic is inscribed in Sanskrit on black marble slabs placed within the niches of these big and small platforms. These slabs have been presently covered by wire mesh and iron angles in order to protect them, one of which is visible in the above photo.

View of a pavilion ('mandap') along with two lower levels of staircases going down to the water at the Rajsamand embankment

One of the three exquisitely engraved marble pavilions ('mandap') on the embankment at Rajsamand Lake

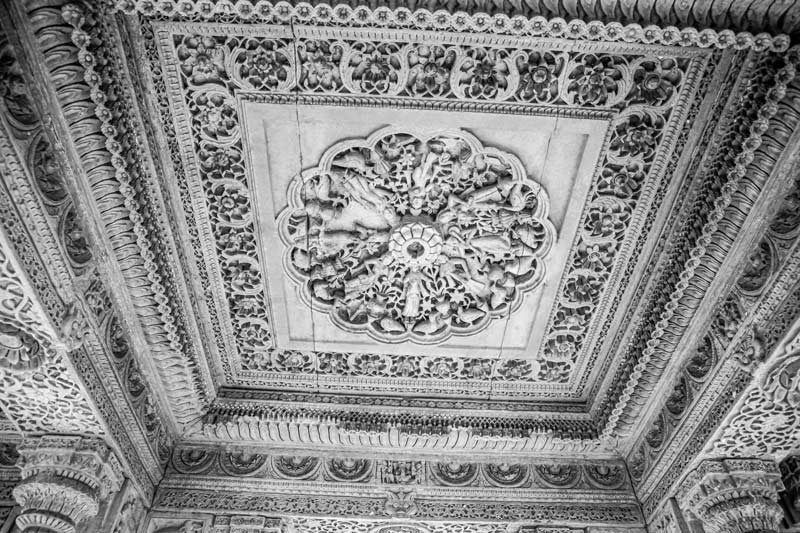

On the Rajsamand embankment there exist three beautifully carved colonnaded pavilions made of marble, one of which is seen in the photo above. Each pavilion comprises a set of 16 equidistant pillars supporting the base of a roof structure. These pillars divide the ceiling into nine square panels of equal size. The pillars as well as the ceiling of each pavilion is decorated with magnificently detailed stone carvings, depicting finely chiseled–out elaborate floral designs and figurines of various gods, chariots, birds, dancing girls, animals and many more. Most of the engraving represents themes from the Indian Puranic literature. It is said that these pavilions were used by the King, Queen and royalty while participating in festivals and celebrations on the lake shore.

Beautiful engravings on the pillars and underside of the roof at one of the pavilions on Rajsamand embankment

Section of a pavilion elaborating the fine engravings on pillars and their adjacent ceiling panel at Rajsamand embankment

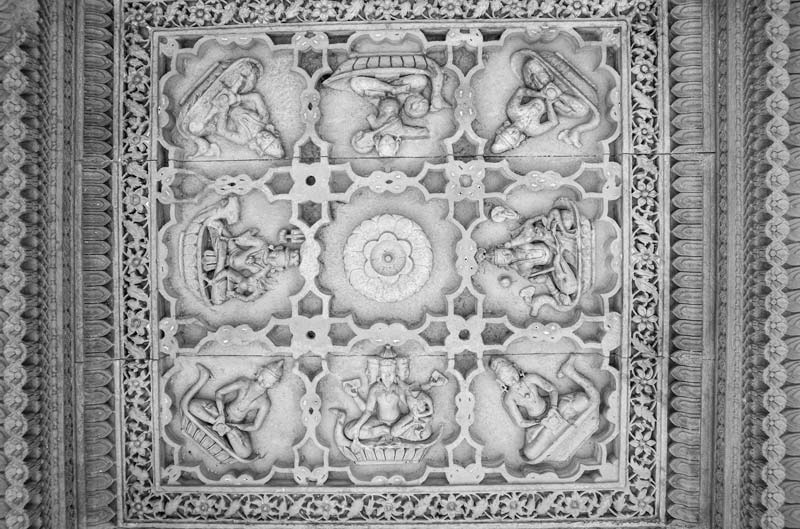

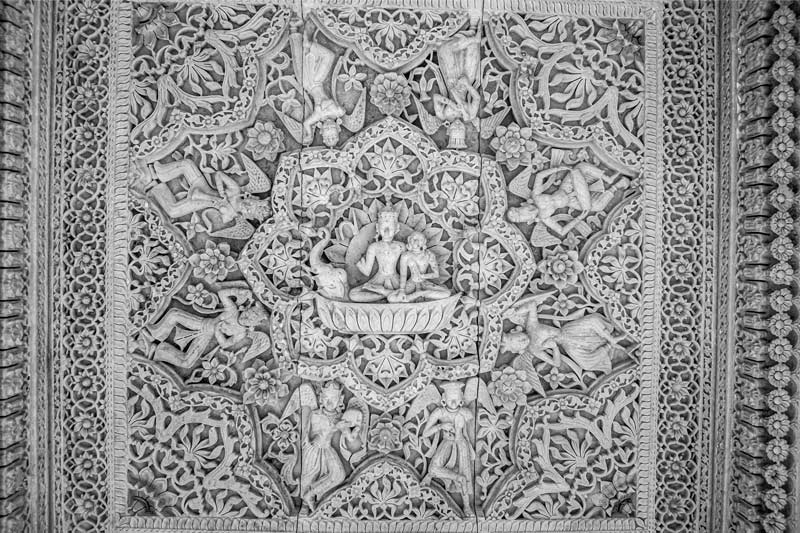

A ceiling panel displaying carvings of multiple celestial beings, birds and floral designs inside a pavilion on Rajsamand embankment

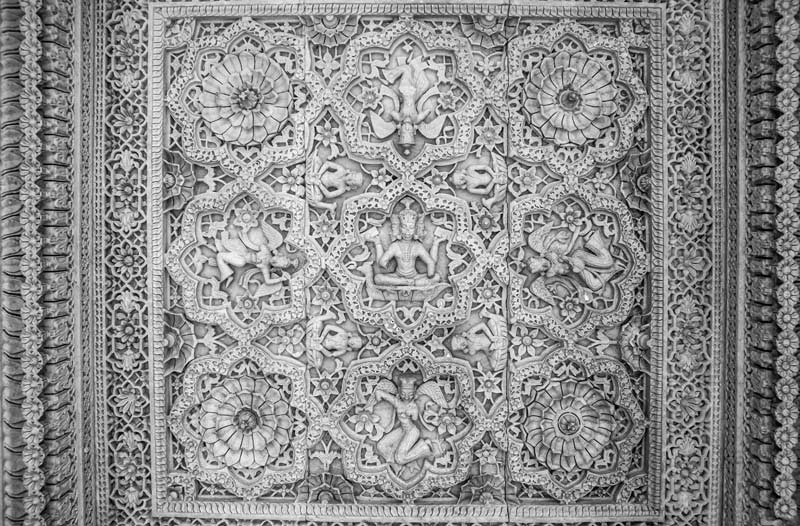

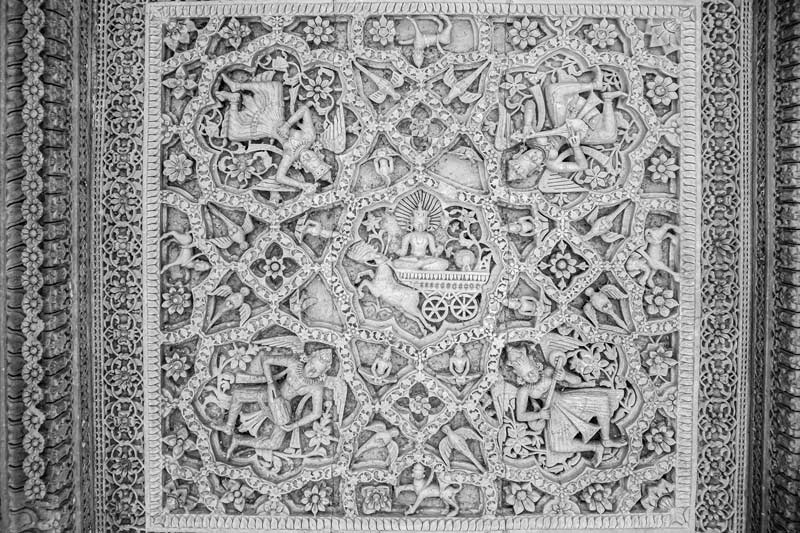

The ceiling of each pavilion is intricately carved and each of the nine square panels there has a different scene engraved, as evident in this and the four subsequent photos.

A ceiling panel inside a pavilion engraved with figures of Lords Brahma-Vishnu-Shiva, along with other celestial beings and floral designs on Rajsamand embankment

A ceiling panel inside a pavilion engraved with figures of Lord Vishnu and Goddess Lakshmi along with other celestial beings, amidst floral designs on Rajsamand embankment

A ceiling panel inside a pavilion engraved with figures of Lord Brahma and multiple celestial beings, placed amidst floral designs on Rajsamand embankment

A ceiling panel inside a pavilion depicting a figure of Sun God together with celestial beings playing music, placed amidst floral designs on Rajsamand embankment

Gateways ('toranas') on Nauchowki at Rajsamand Lake

Another artistic feature at the Rajsamand embankment are the five gateways ('toranas'). These stand on the smaller platforms across the Nauchowki, at the third level of staircases from the top. Each gateway is made of two pillars with a transverse stone beam on top, above which a well-designed arch is placed. The pillars, arches as well as the beam are all exquisitely engraved with different kinds of motifs. It is believed that these gateways, also referred as weighing arches, served as sites where the king Maharana Raj Singh I and other members of royalty used to organize the event of 'Tuladan'. On this occasion, they were weighed in jewels and gold, silver and precious metals. After weighing, these metals or equivalent cash value were distributed to the poor or to Brahmins or for construction of temples and tanks for public welfare. Only one 'torana' remains almost intact today, while the rest are damaged to different degrees.

The gateway ('torana') on Rajsamand embankment which remains nearly intact in present times

The only surviving artistic arch atop the gateway ('torana') at Rajsamand embankment

Water-related art and architecture in Rajasthan is known to be scientifically as well as aesthetically rich, and Rajsamand Lake and its magnificent embankment bear a testimony. The artistic and architectural excellence here can be seen as closely connected to a number of cultural dimensions, serving important functions. These primarily reflect the spheres of religion, economy, polity and social welfare. The very purpose of the construction aimed at socio-economic upliftment and welfare of the populace affected by drought through long-term employment. The water stored in the lake as a result of the embankment provided for groundwater recharge in the vicinity, in turn providing drinking water, and the water could also be drawn for agriculture. The design principle of 'nine', which underlines the entire construction, is fundamentally embedded in the Hindu religious philosophy. The patterns and motifs of the beautiful engraving on the different structures on the embankment are again rooted in the realm of religion, derived mainly from Puranic and other religious texts. It can be contended that the close connection of the structure with religious philosophy ascribed sanctity to Nauchowki, which must have contributed to the protection of the lake and upkeep and maintenance of the structure. Simultaneously, for the royalty, it was a site for celebrating festivities together with the citizens, and for launching of public welfare activities. It was also possibly a leisure spot for the royalty. The exquisiteness of the lake and its embankment must have on the whole, been a mark of pride for the kingdom – the rulers as well as the citizens and allowed everyone a locale for connecting to nature. Its magnificence must have also always attracted tourists from far and near and helped people enjoy peace, tranquility, health and wellbeing. Not to forget that the great epic 'Raj Prashasti' written on the slabs at the embankment represented a political commentary about the kingdom that created it and its greatness.

The art and architecture at Rajsamand embankment is thus an important cultural heritage related to water. And this is further closely connected to the current discourse on "valuing water" promoted by the United Nations. According to this discourse, water has enormous and complex value in society which can be understood from five different perspectives, namely: valuing water resources, valuing water infrastructures, valuing water services, valuing water as an input to economic activity, and valuing socio-cultural aspects of water. The above account about the Rajsamand embankment touches upon all these different dimensions, and demonstrates two important things: first, how in the process of valuing water, art and architecture plays a vital role; and second, how by valuing water-related art and architecture, water resources themselves get valued.

What is important about Rajsamand embankment is that not only is it a heritage from the past, but it is a living heritage meaningful in contemporary times, and holds unparalleled importance for the future. Its architectural strength and robustness continue unabated in contemporary times and cause the lake to survive and continue to serve many vital functions as before. The embankment itself is known far and wide for its uniqueness, size and beauty and attracts thousands of tourists every year. And it further continues to inspire many others to value water along similar lines. However, today the lake embankment is at risk. There have been changes in the engineering of the lake afterwards, such as construction of sluice gates, with the result that the maximum water height in the lake has increased. This causes the beautiful art and architectural forms to submerge under water in the years of heavy rainfall, exposing them to risk of damage. There is also discoloration of the stone, and the carvings are getting broken and also losing clarity due to weathering. The gateways ('toranas') are also heavily damaged. There has been gross neglect from agencies that could have acted towards its preservation and maintenance. There is an urgent need to protect and maintain this important water-related heritage so that water continues to be valued and helps ensure the survival and sustainability of society and nature dependent on it. In fact, this emerges as a general message applying to all our water-related heritage so that sustainable development can be promoted.