Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and CultureA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2022

Groundwater: Its Value for Cultural Services

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

18 July, 2022

Groundwater is the water below the land surface present in pores, fissures and other voids in underground geological units, such as permeable rock or unconsolidated materials. These units, commonly referred to as aquifers, combine the functions of groundwater reservoir and ‘highway’ for groundwater flow. These may extend vertically from very close to the land surface down to thousands of meters. Groundwater accounts for approximately 99% of all liquid freshwater available on Earth and large volumes of fresh groundwater are present below ground surface and distributed over the globe. Since it cannot be seen on the earth’s surface, groundwater is ‘invisible’. However, it is a highly valuable resource for society and the ecosystem. In fact, it is an integral component of the ecosystem and many aquatic ecosystems such as springs, wetlands, estuaries, and baseflow in rivers and streams; and also terrestrial ones, such as forests and woodlands that rely on groundwater in dry season, and phreatophytes, are dependent on groundwater. Thus, groundwater provides a number of critical ecosystem services (or benefits) for human beings, which are further classified as provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural services. Provisioning services mainly comprise water storage and supply for fulfilling agricultural, domestic, industrial and other kinds of societal needs. At the global scale, largest share of the total volume of abstracted groundwater (at 69%) is taken for irrigation alone, while 22% is used for domestic purposes, and 9% for industrial use. In India, according to a recent estimate by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), out of a total annual groundwater extraction of 245 billion cubic meters, as much as 89 % is meant for irrigation, while only about 11 % is for domestic and industrial use. Regulating services provided by groundwater and groundwater-dependent ecosystems (GDEs), include buffering between wet and dry periods through water storage and conservation, erosion and flood control, water purification from microbial and chemical contaminants, and climate regulation. Supporting services are those that are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services and include supporting the ecology for subsurface life; habitat provision for aquatic and terrestrial life through springs, stream baseflow, and subsurface water; and control of land surface stability. Cultural services are the nonmaterial benefits people obtain from groundwater and GDEs. These are tightly bound to human values and behavior, as well as to social, economic, and political institutions in society, and relate to spiritual and religious values, cultural heritage, recreation and leisure, aesthetic and inspirational experiences, education and cognitive development. A lot of attention has so far been given to the provisioning services obtained from groundwater. In recent years, given the context of climate change and other global changes, there also exists an increasing emphasis on the regulating and supporting services offered by groundwater and GDEs. However, the cultural services provided by groundwater and its associated ecosystems remain under-explored. This photo story aims to focus on this lesser known dimension and elaborate how groundwater and GDEs help society uphold spiritual and religious values, create and preserve cultural heritage, facilitate recreation and leisure, gain aesthetic and inspirational experiences, and promote education and cognitive development. The title photo depicts Kushavarta Kund – a 21 ft deep sacred tank fed by groundwater. Located on the footsteps of Brahmagiri Hills at Trimbakeshwar, district Nashik, Maharashtra, this tank is ascribed a high ritual value by Hindus and denotes the place from where river Godavari, or Dakshin-Ganga (Ganges of the South), takes its course.

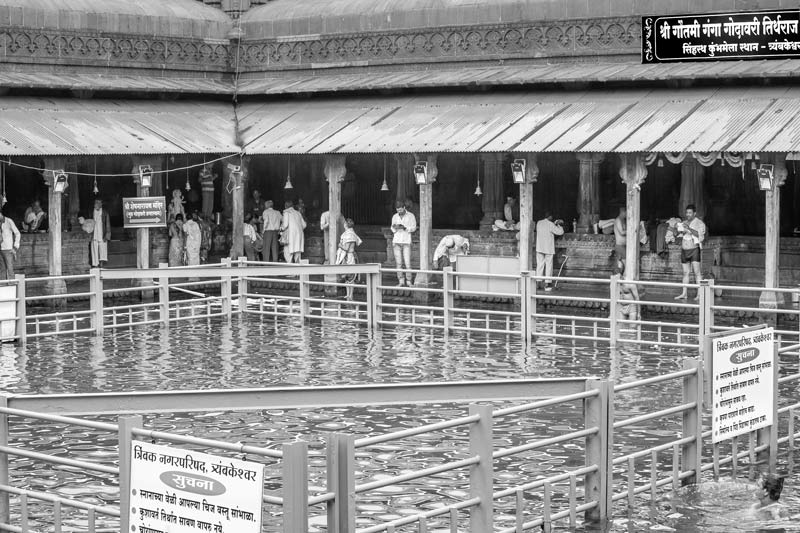

Kushavarta Kund which marks the point of appearance of Godavari River from underground, at Trimbakeshwar, Nashik district, Maharashtra

One of the significant cultural services provided by groundwater concerns spiritual and religious values. In Hinduism, there exist a number of groundwater-dependent holy tanks and ponds holding spiritual and religious values. An important example is the Kushavarta Kund from where River Godavari originates, as shown in the photo above. The exact point of origin is said to be Shri Sheshnarayan temple, located within the tank premises. According to an interesting Hindu legend, Sage Gautam once committed the sin of killing a cow. To absolve the sin, he performed penance on the peak of Brahmagiri Hills in the Western Ghats, appeased Lord Shiva and asked for the Ganges waters to wipe off his sin. Pleased with his devotion, Lord Shiva sent down Ganges from His big locks of matted hair onto Earth on Brahmagiri at Gangadwar. However, the flow of Ganges was so fierce that the Sage could not bathe in her waters. After this, Ganges appeared off and on the hills at a number of places, but still, he could not bathe. Finally, the Sage surrounded the river with enchanted grass (kusha) at the footsteps of Brahmagiri and put a vow to her. The flow stopped there, and the Sage could finally bathe to wipe off his sin. Kushavarta thus came into being as an important pilgrimage spot.

Pilgrims bathing in the waters of Kushavarta Kund on the occasion of Nashik Kumbh at Trimbakeshwar, Nashik district, Maharashtra

Seen from an ecosystem perspective, the Hindu legend described above indicates that Godavari emerged first as spring along the hill slope, disappeared a number of times, finally to re-emerge from the underground aquifers at Kushavarta. It is said that this tank never dries up, which further testifies groundwater as the source. Following Sage Gautam’s legend, Kushavarta Kund, and hence her water is imbued with the ritual value of freedom from sins for anyone who takes a holy bath (snan). Also, Gangadwar and some other spots on Brahmagiri are of religious importance. One of the important occasions for ritual bath at Kushavarta is the Nashik Kumbh which is held once every 12 years. Kumbh is the oldest and most well-known ritual bathing festival of India, known to be performed perhaps since Rig Vedic times (1700-1100 BCE) at four different places in the country. One of these is the Nashik Kumbh. Other auspicious occasions for ritual bath at Kushavarta include Kartik Purnima and Makar Sankranti. The tank is actually visited round the year by thousands of pilgrims to achieve purity of the body and soul, and liberation from sins through a holy dip. Besides the religious significance, Kushavarta as the source of River Godavari, and the natural beauty of Brahmagiri Hills which is supported by groundwater for a large part of the year, are also a great general tourist attraction.

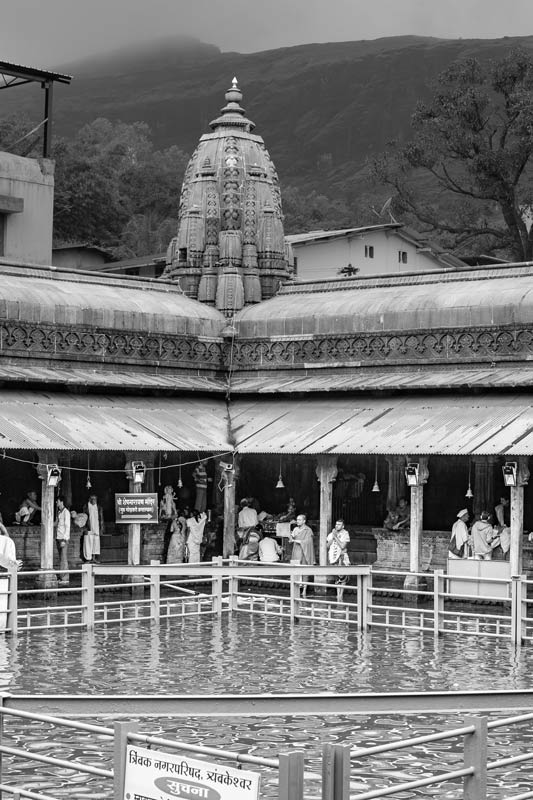

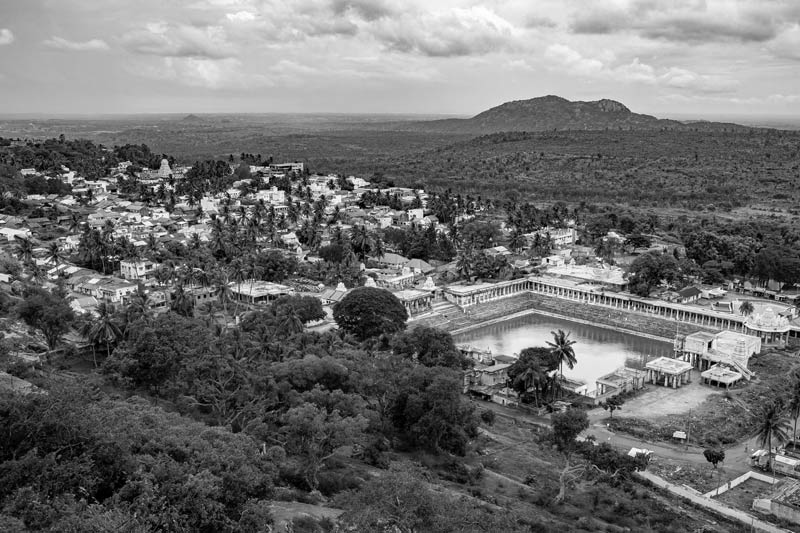

The temple town of Melkote in Mandya district, Karnataka, with the large sacred tank called Yoga Narasimha Swamy Kulam on the right

Spiritual and religious values are also closely connected to cultural heritage, and one good example of this comes from the sacred tanks of Melkote in Mandya district, Karnataka. Located in the Yadavgiri Hills, Melkote is a heritage town which has been a prominent centre of Srivaishnavism, with a history of about 1000 years. Situated at a height of more than 3,600 ft above sea level, this town lacks a source of flowing water. Thus, rain is the only water source which is captured through an intricate system of tanks and ponds on the hill slopes, which are said to be 108 in number. Many of these are regarded as ‘sacred’, and ascribed spiritual and ritual values. The biggest and ritually most important is the Yoga Narasimha Swamy Kulam (also known as Panchkalyani). The tanks of Melkote help intercept most of the rainwater that would have otherwise disappeared down the slopes, thus making a unique rainwater harvesting system. While this aspect has attracted much scientific attention, lesser discussed is the groundwater recharged in this hilly region through the rainwater harvesting, and the role of the latter in ensuring round-the-year water availability in the sacred tanks and associated wells, thus facilitating different ritual activities. This aspect is described in detail in the context of Panchkalyani below.

Yoga Narasimha Swamy Kulam (sacred tank), and its associated temple atop Yadavgiri Hill, in Melkote, Mandya district, Karnataka

The Yoga Narasimha Swamy Kulam (or Panchkalyani) is a sacred tank located at the foothill of the Yoga Narasimha Swamy temple, where Lord Vishnu is worshipped in his Narsimha incarnation. Panchkalyani is a huge tank surrounded by corridors held up by stone pillars which are beautifully carved. As shown in the photo above, between the corridors and the tank are a series of steps on all four sides leading down to the water. The total estimated depth of the tank is 27-33 ft (8-10 m) below the ground level, taking together the steps and the depth of water. According to CGWB’s Mandya district report, this is precisely the depth of pre-monsoon water table in the area. Further, according to a hydrogeological observation on sacred tanks in South India, a minimum tank depth of 8 m below ground level opens up the possibility of groundwater supply from the phreatic aquifers by the effect of gravity. It can thus be inferred that the Panchkalyani, and probably also other sacred tanks in Melkote, had a dual water supply source – harvested rainwater during monsoon and groundwater during the dry season. This is corroborated by the fact that there exist five wells connected to Panchkalyani which act as indicators of the groundwater level at all times. Of these, the one called Anandamaya never dries up. Thus, through a combination of rain and groundwater, Panchkalyani ensures its ritual services as a perennial water source. Its water is used by devotees to cleanse themselves before vising the Narsimha Swamy temple on the hilltop, besides its association with a variety of everyday and festive rituals. Melkote is an important religious as well as tourist destination, and Panchkalyani and other sacred tanks are frequented round the year by thousands of domestic and international visitors. Many of these are simply attracted by the aesthetics of the tanks, temples and the natural beauty of the place.

A constructed tank filled with groundwater amidst the dry bed of sacred Devyani Kund in Sambhar Lake town, district Jaipur, Rajasthan

In recent times when surface water is becoming increasingly scarce, groundwater has come to the rescue of cultural sites that were previously surface water based. At a number of places, groundwater has been added as a source to feed such traditional (sacred) ponds and tanks so that their spiritual value can be upheld. An interesting example is a sacred pond called Devyani Kund in Sambhar Lake town, district Jaipur, Rajasthan. It is an important Hindu pilgrimage, regarded as the "grandmother of all pilgrimages", where Ashwatthama, a hero of the epic Mahabharat, is believed to have come for performing penance. Thousands of pilgrims and local devotees, including many women, flock here every year on the occasion of Baisakhi Purnima (in April) for holy bath. Other important occasions are the month of Kartik (in October-November) and five days every month from Ekadashi (11th day) to Purnima (full moon) dates. It is also an important site for ancestral worship (pind-daan). Historically, Devyani Kund was rainfed and used to retain water round-the-year. However, some decades back, it started drying up shortly after monsoon. In order to prevent disruption of its religious function, a smaller cemented tank – called Annapurna Ghat - was specially constructed for women in one part of the pond. This used to be filled by groundwater, and women could undertake ritual bath, as seen in the photo above. Soon after the above photo was shot in 2016, Devyani started receiving intermittent surface water supply from Bisalpur Dam, and the groundwater from Annapurna Ghat was also regularly drained out into it. As a result, the larger pond now retains enough water for women to bathe at the renovated old Radha Ghat along the original banks of Devyani. Annapurna Ghat, still filled by groundwater, now stands reserved for men and boys.

An artificially constructed groundwater-fed tank for sacred use in a village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Besides rescuing older religious and cultural heritage sites, groundwater also provides the cultural service of enabling the continuation of traditional beliefs and practices at new alternate sites. As already evident from a number of above examples, holy bath is an important component of Hindu rituals. Also, on some occasions, as in Chhath Puja, the worship itself is to be performed standing in water in a river, pond or another source. In recent times, when there is lack of clean water in rivers and ponds, or nearby natural water sources have dried up, groundwater has come to offer a new prospect in this regard. One such instance is illustrated in the photo above. It depicts the situation in a village where the communal sacred pond near the village temple complex where devotees used to perform holy bath and other water-related rituals such as Chhath Puja has fallen prey to misuse and mis-management. Not only does the village wastewater drain into the pond, but it has also been converted into a fish farming tank by some greedy politically and economically dominant villagers, thus rendering it unusable for religious purposes. In response to the crisis, an artificial cemented tank has been constructed by one of the villagers as an alternative. This tank is filled up with groundwater at the time of religious festivals like Chhath Puja and used as a communal sacred tank by the villagers.

Women performing Chhath Puja in the artificial tank shown above in a village in Bhojpur district, Bihar

Chhath Puja is an ancient Hindu Vedic worship which is traditionally performed while standing in water in a river, pond or other water source. The worship is dedicated to the setting and rising Sun god (along with his wives goddesses Pratyusha and Usha respectively) and to 'Chhathi Maiya'. The latter is believed to be a form of Devi Parvati (mother goddess) and Lord Surya's sister, or else daughter of Lord Brahma. The festival is spread over four days, of which on the third day at dusk and the fourth day at dawn, offering (or arghya), comprising sacred water and food, is made by the devotees while standing in waist-deep water. Besides they also meditate and pray for long periods of time in the same position. According to ritual norms, families that start performing this worship must continue its observance every year. When the communal sacred pond became unusable for religious purposes in the village as described above, this norm was challenged. Construction of the new tank, and filling it up with groundwater, has addressed the crisis, and now, villagers are able to carry out the Chhath rituals and other observances without any hurdle.

The point of origin of Arkavathy River at Nandi Hills in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka

Leisure and recreation is an important dimension of the cultural services provided by groundwater. Nandi Hills in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka is a famous tourist destination visited widely by domestic and international tourists. Since it is quite close to Bengaluru, it is also the perfect weekend getaway for the city’s residents. It is well-known for its historical fortress, and a number of temples, monuments and shrines, but it is equally popular among nature-lovers for its beauty and greenery. An important tourist spot in this regard is the origin point of River Arkavathy, which is located in the Channakesava Hills of the Nandi Hills range, at an elevation of 1,478 m above the sea level. The river originates from a hill spring that forms a small pond, as seen in the photo above. It is a beautiful, serene spot where tourists can sit and relax. From this pond, the water moves down the hill, passing through a series of 26 man-made reservoirs that have been built to hold its water for irrigation and drinking purposes. Thereafter, it flows as a river for 190 kms to join River Kaveri at the Kanakapura confluence in Bangaluru Rural district. It is also noteworthy that much of the greenery in Nandi Hills that attracts tourists is actually supported by groundwater because the average annual rainfall is quite low at only 756 mm, and mainly restricted to six months in the year.

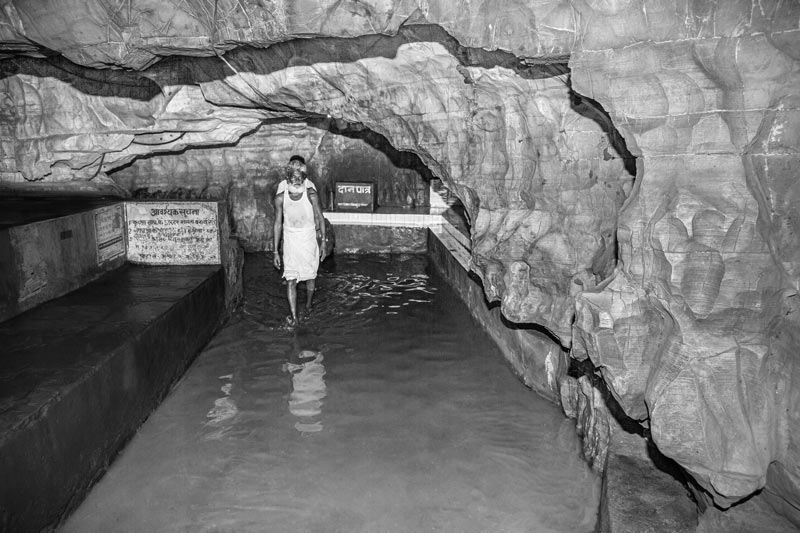

Gupt-Godavari caves in Satna district, Madhya Pradesh

Gupt-Godavari is yet another site supported by groundwater which is a famous religious and tourist destination nestled in the Panna range of the Vindhya mountains. Located in Satna district, Madhya Pradesh, it is a secret ceaseless stream that arises in the caves and disappears quietly, thereby denoting a treasure of nature that is of divine origin. The site comprises a pair of caves that are marvelous and beautiful with natural carvings in varied designs. The caves are dated to be 9,50,000 years old. The higher one is accessed through a narrow passage with a low roof that allows only one person at a time. It opens up to a wide cavern, and a pool of spring water called the Dhanushkund. There are many small shrines here, and beautifully carved natural sculptures, notably two natural throne-like rocks said to have been used by the legendary Lord Rama and Lakshman who stayed here for some time during their exile. Outside the cave, there is a remarkable Panchmukhi Shivalinga that features the holy trinity – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. The second cave has a wider entrance and has a stream of water that originates in the cave above from Dhanushkund. This water disappears into a crevice making its secret, underground way back into the mountains. The legend is that River Godavari desired to see Lord Rama, and hence she came here secretly from Trimbakeshwar, Nashik in Maharashtra. So, she is called Gupt (secret)-Godavari. After emerging from the cave, she flows into a pond and then vanishes in the mountains. The place has a divine bliss with a calm and cool atmosphere, with the water being just 12 to 14 degree Celsius.

Mani-kinar - a sacred well belonging to Ambalappuzha Sri Krishna Temple in Alappuzha district, Kerala

Groundwater has been used widely in rural communities and also in many urban centres not only for drinking and other domestic uses, but also for religious purposes at domestic as well as communal levels. This has been done traditionally through wells and the modern sources - handpumps, tubewells and groundwater-based water supply systems. At many places, religious and spiritual values associated with groundwater are traditionally manifested through sacred wells associated with temples. The above photo shows one such traditional sacred well called mani-kinar located within the premises of Ambalappuzha Sri Krishna Temple in Alappuzha district, Kerala. The temple is famous for its unique prasadam - the delicious Ambalapuzha Palpayasam – a sweet porridge made of rice, milk, water and sugar. Water for preparing this prasadam is drawn only from mani-kinar. The prasadam is prepared every morning between 5-7 am and first offered to the deity before being distributed to devotees.

A temple well in the dried-up Vaigai riverbed in Madurai, Tamil Nadu

In some instances, sacred wells have been more recently dug as a solution to procure sacred water at a dried-up surface water source that itself was revered. Madurai is one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited religious centres, with a rich cultural heritage passed on from the great Tamil era, which is more than 2,500 years old. The lifeline of this heritage town has been River Vaigai, which is believed to have been born from Lord Shiva’s locks when he came here to wed princess Meenakshi. Thus, Vaigai became a sacred river, with a number of religious festivals traditionally celebrated on its banks. The river reportedly used to ‘flow to its brim’ most of the year round. However, over the last two decades, the riverbed has started remaining almost dry throughout the year, even during the monsoon months. This caused persistent difficulties in performing the rituals connected to river Vaigai and its waters. In order to safeguard the devotees’ interests, and prevent any untoward dampening of the religious spirit, temple wells were dug in the dried-up Vaigai riverbed which supply groundwater from the phreatic aquifers underlying the river course. While ritual bath is no longer possible in the river, groundwater from the wells enables the devotees to take holy bath, and also perform various rituals. The above photo shows a sacred well belonging to the Meenakshi Sundereshwarar Temple – the cultural icon of Madurai. The water from this well is reserved for abhishek (anointing) of the temple deities.

The stepwell Chand Baori – an architectural marvel in Dausa district, Rajasthan

Yet another example where groundwater has served important cultural services are the stepwells in the semi-arid and arid regions of northwestern and western India. Starting with a rudimentary form as early as the 3rd century CE, several thousand stepwells in varying degrees of grandeur had been built by the 19th century. One such architectural splendor and a unique cultural heritage is Chand Baori in Dausa district, Rajasthan. One of the biggest and deepest stepwells in the world, it was built in the 9th century CE by King Chanda, who ruled erstwhile Abhanagar (now village Abaneri). The well tapers towards the bottom to a depth of about 64 ft (19.5 m) beneath the ground, reaching into the aquifers below. The source of water was rainfall, surface runoff and groundwater. It has about 3,500 steps running on three sides through 13 floors, of which the last two are always submerged. Being groundwater-fed, the well never dries up. The fourth side of the well originally had a ramp for animals to drink water, where in the 16th century CE, a royal summer palace was constructed by the Chauhan dynasty. The bottom part of the stepwell has temples dedicated to Lord Ganesh and Goddess Mahishasur Mardini. Around the 18th Century, Mughals embellished the upper levels with pavilions and arcades. As a stepwell, through the centuries, Chand Baori has provided important cultural services, besides provisioning services. At the bottom of the well, the temperature remains 5-6 degree Celsius cooler, and therefore, it served as a point of community socializing especially during periods of intense heat. Later, though closed to the public, the royal family used it for leisure (summer vacations), and also participation in religious festivities dedicated to the Goddess. Today, the timeless beauty of this architectural marvel continues to draw huge number of domestic and foreign tourists, and also educates for sustainable water management practices in an era of water crisis, inspires technical and business designs, besides promoting cinema and recreation.

Rani Dhara – a well-known spring-fed water source in the heart of Almora town in Almora district, Uttarakhand

Springs are an important groundwater-based source in mountainous regions that provide drinking water for local residents as well as several cultural functions. The mighty Himalayas are estimated to be home to three million springs. Dhara and Naula are the two major kinds of spring sources used widely in local communities of Uttarakhand in rural as well as urban areas. A dhara resembles a drinking water fountain where groundwater from the aquifer flows out through a fissure, crack or other kind of exit point onto the surface. This water is channeled through a pipe or a carved outlet. Naula, on the other hand, is designed to collect water from subterranean seepage springs. The seepage is collected in a tank that is closed on three sides and covered. The fourth side, which is open, has steps that lead down to the water. There is a pillared verandah around them with engravings, the purpose mainly being protection of the water. Sometimes, dhara are similarly protected, with a tank constructed to hold the emerging water, and an outlet through which the water is collected. Naula and dhara may be adorned with intricate architectural designs, often housed in aesthetically constructed temple-like structures. Rani Dhara, shown in the photo above, is a centuries old temple-shaped dhara located in the heart of Almora town. It is located within a picturesque natural setting on the side of a hill and continues to be used and maintained by the local residents.

An image of God imparting sanctity to Rani Dhara - a spring source in Almora town, Almora district, Uttarakhand

Naula and dhara as spring-fed water sources in Uttarakhand are not only used for collecting water for drinking and other domestic uses, but also provide water for religious purposes at domestic and communal levels. These are thus revered places where sanctity of the water as well as the structure is important. As a result, these may be associated with temples or else, have images or figures of gods and goddesses installed inside. Rani Dhara as a spring-fed water source is imparted sanctity through the image of God on its wall, as shown in the photo above. The rules of its usage ensure that sanctity and purity of the place are maintained, and any activities that would lead to contamination or destruction of the source are considered as sinful.

Women socializing within the premises of Rani Dhara - a spring source in Almora town, Almora district, Uttarakhand

The premises of naula and dhara as spring-based water sources also serve an important cultural function – as centers of interaction and socialization. Rani Dhara as a spring-based water source is not only a place for fetching clean drinking water, but it also serves an important social function, especially for women and girls, who as domestic water managers are the main users of the spring. They may meet each other at random or even come in small groups to fetch water. But once on site, they may sit together for a while, gossiping or discussing important family matters or simply enjoying some moments of leisure out of their busy daily chores within the picturesque, serene setting of the Dhara.

The springfed Dhokaney Waterfall in Nainital district, Uttarakhand

The Himalayan springs also provide cultural services for leisure and recreation through several thrilling and beautiful waterfalls. These waterfalls attract numerous domestic and foreign tourists from far and wide, who come to the Himalayas for enjoying the beauty of nature. Dhokaney Waterfall, shown in the photo above, is one such adventurous place fed by springs which is located between the hill stations Almora and Nainital. It is located high up in the Kumaon Hills at an altitude of 1,395 meters. It is a spectacular waterfall amidst magnificent pine forests, a locale which offers a great option for enjoying a full day picnic in the laps of nature. The water falls down from the cliff into a pool surrounded by mountains. Around the pool, there are benches to sit down, relax and enjoy the serene beauty and have fun. One can also swim in the water or just play around and have fun near the waterfall. It is noteworthy that much of the natural beauty in and around the waterfall is supported by the springs and aquifers running along the mountain slopes.

Jaisaloo well – a historical groundwater-based source inside the famous Jaisalmer Fort, in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Jaisalmer Fort, a UNESCO World Heritage site and India's only 'living' fort, is one of the most magnificent monuments standing in the middle of the unending golden sands of Thar Desert in Rajasthan. Built in 1156 CE by Rawal Jaisal, the fort is one of the most prominent tourist destinations of Jaisalmer. Among its various attractions are included several dugwells, which were dependent on the local aquifers. One of these – known as Jaisaloo well – is shown in the photo above. Once having the provisioning role of supplying drinking water to the fort inmates, today the well also provides multiple cultural services - related to history and cultural heritage, leisure as well as education, bearing testimony to the rich traditional knowledge on accessing water in the midst of the Thar Desert.

A view of Naini Lake with its boating facility in North Delhi district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Wetlands are naturally dependent on runoff as well as groundwater flows and support a variety of aquatic and terrestrial flora and fauna. This, in turn, promotes nature tourism and leisure activities in different forms. However, rapid urbanization has adversely affected the water availability in many such lakes and ponds located in or near urban areas through multiple pathways, thereby also thwarting their cultural services. In such instances, groundwater extracted through deep tubewells has been adopted as a solution to tide over the crisis and revamp the cultural services. Naini Lake in the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD), shown in the above photo, is one such instance. Historically, this was a natural lake mainly based on runoff from its local catchment, along with groundwater supply from the rather shallow phreatic aquifers in the dry season. The lake represents an open relaxing blue-green space amidst residential colonies and has been a popular leisure and tourist destination in the northern part of the city. Here people can enjoy a weekend picnic with family and friends and also go for boating. There is also a small island in the middle of the lake, with trees that shelter water birds. The lake is surrounded by well-built promenades for walking and culverts for relaxing after the walks. The periphery is lined with palm trees and the entire lake area presents tranquility which is a pleasant respite from the urban hustle and bustle. However, from 1960s, the runoff got obstructed due to urban development all-around, and the water table started to progressively plunge, sounding alarm bells for the lake’s survival. Under such circumstances, the lake and its associated leisure facilities have been given a new lease of life by restoring the water level using groundwater pumped out through tubewells.

This story has elaborated in depth how groundwater – the invisible resource – is an invaluable resource for society because of the crucial cultural services that it provides. It has presented glimpses of how groundwater, together with the ecosystems dependent on it, help society uphold spiritual and religious values, maintain cultural heritage, enable recreation and leisure, acquire aesthetic and inspirational experiences, and provide new learning. A number of these examples also show that groundwater does not necessarily exist in isolation, locked in aquifers. Water sources like ponds, tanks, stepwells, wells, springs and even rivers are actually based on the integration between surface- and groundwater. It is important to understand this continuity as a part of the water cycle while elaborating the ecosystem services offered by groundwater.

It further emerges from the above account that three kinds of cultural services provided by groundwater may be distinguished. First are those that are directly provided where the groundwater is physically visible in the source. Examples are springs, stepwells, tanks and streams. Second is where the groundwater itself is not visible but contributes indirectly to provision of the service. Here examples include the services through GDEs, such as the natural beauty on mountains or greenery around springs and waterfalls. Third is the service provided by groundwater in contemporary times to replace surface water and thereby enable continuation of cultural beliefs and practices. Examples here include use of extracted groundwater to refill tanks or lakes that earlier provided important cultural services. These three kinds of cultural services may be labeled as ‘direct’, ‘indirect’ and ‘replacement’ cultural services of groundwater.

Given the value of groundwater and GDEs in providing the diverse cultural services for humankind, it is important to ensure that these services can continue in contemporary times as well as in the future. This in turn requires adequate availability of clean groundwater at appropriate depths. However, this important prerequisite is getting increasingly challenged in present times. These challenges and their possible solutions will be presented in the forthcoming photo stories. In fact, the ‘replacement’ cultural service itself may invite substantial criticism because filling up of tanks and lakes requires withdrawal of colossal amounts of groundwater which are difficult to be restored.