Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and EnvironmentA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2018

Degradation of Nature and its Impact on Water

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

21 April, 2018

The importance of nature for water is indisputable and its role in producing, augmenting and conserving water, which in turn enables flora and fauna to thrive and human civilizations to flourish, has been elaborated through the example of the Himalayas in India in the story dated 22 March 2018. Despite this indispensable relationship, in recent times, nature has come to be used indiscriminately for fulfilling not only the basic needs but for satisfying the greed of humankind. Denudation of forests and degradation of natural landscapes have been among the most common forms of human onslaughts on terrestrial ecosystems in India. Research shows that in 1930 forest cover in India was 869,012 sq. km. but in 2013, this area has decreased to 625,565 sq. km. - a net loss of 243,447 sq. km. (28%) in eight decades. According to the latest India State of Forest Report, 2017, over 21,000 sq. km. of standing forests have been completely denuded during the two-year period 2015-2017 alone. Causes of deforestation and landscape degradation are several, and largely include creation of human settlements, agricultural lands, commercial plantations, mining of valuable minerals and metals, hydropower generation, industrial development, and commercial logging. Disappearance of forests has affected the water cycle in multiple ways. It has reduced cloud formation as well as the ability of clouds to cause precipitation, thereby decreasing precipitation. Moreover, without forests water cannot be retained in soil as ‘green’ water, in turn impeding aquifer recharge as well as causing floods; while lesser precipitation and reduced aquifer recharge together also result in drying of streamflows and droughts. In addition, deforestation has led to removal of the carbon sink, in turn contributing to atmospheric warming, with spiraling of the impacts on water. Landscape changes can impact water through several pathways, such as interference with natural drainage networks (subsurface as well as surface flows), altered water use patterns and pollution caused by the new human activities, besides the effects caused by deforestation. This photo story aims to present glimpses of degradation of nature through deforestation and change of the natural landscapes in India with focus on terrestrial ecosystems and how these have impacted water. The title photo depicts an open-cast coal mine in Jharia Coal Fields in Dhanbad district, Jharkhand. The expanse and extent of degradation of nature through deforestation and landscape change resulting from this activity is overtly evident.

Coal being extracted from an open cast mine in Jharia Coal Fields in Dhanbad district, Jharkhand

Mining is one of the top sectors for which large-scale deforestation has taken place in India. The country possesses significant reserves of important minerals and ranks among top producers of chromite, coal, lignite, barites, iron ore, bauxite, crude steel, manganese ore, mica and aluminum. According to one estimate, there exist over 3,100 mines in the country, with the States of Jharkhand, West Bengal and Orissa recognized as the ‘mining heartland’. During the last 30 years alone, government has granted permission for clearing 4,947 sq.km. of forest land for mining purposes. Mining not only entails denudation of forests, but also massive landscape changes, which gets even more pronounced due to the common practice of open cast mining, and non-compliance of systematic mine closure, and reclamation, rehabilitation and restoration obligations for ecosystem regeneration by the mining companies. The coal reserves of India are the fourth-largest in the world at about 300 billion tonnes, with Jharia Coal Fields (JCF) as the most important storehouse of coking coal used in blast furnaces. Spread over a previously forested area of 280 sq. km., JCF consists of 23 underground and nine large open cast mines, one of which is shown in the above photo. Coal mining, an economic activity in the area since 1894, has led to large-scale ecological degradation, with massive deforestation, wastage of groundwater through dewatering, water pollution, and worst of all, underground fires blazing in the coal seams for over a century which itself causes warming of the land surface and air, besides drying up the underground aquifers. All these ecological consequences of mining have seriously impacted the water resources in the area.

Denuded forest lands in Cherrapunji (Sohra) in East Khasi Hills district, Meghalaya

‘Forest’ has been defined by the Forest Survey of India as all lands more than one hectare in area with a tree canopy density of over 10%. The North-Eastern Region of the country comprising the eight States – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura - is endowed with rich forest resources. The region, comprising just about 8% of the geographical area of the country, accounts for nearly 25% of its forest cover. It is also one of the highest rainfall‐receiving regions on the planet, the rich forest cover being the single most important factor. However, deforestation has been rampant in the region. In Meghalaya, where forests covered more than 76% of the geographical area, deforestation has been rampant, and during the two-year period of 2015-2017 alone, a decrease of over 116 sq. km area has been recorded. Meghalaya, literally the ‘abode of clouds’, enjoys the distinction of having two of the world's wettest places: Cherrapunji and Mawsynram. In July 1861 Cherrapunji received 9,296 mm of rain, and between August 1860 and July 1861, the rainfall was 26,477 mm - a world record. In recent decades, the annual rainfall has reduced to less than one-third. According to meteorologists and environmentalists, the single cause behind the reversed situation is deforestation caused by mining, industries and illegal logging. ‘Cherrapunji’ means the 'land of oranges', and thereby orchards, but today trees have become a rare sight as evident from the photo above and the area suffers acute water scarcity when the rainfall starts to drop sharply from November until March.

Stocks of timber at a saw mill in Dimapur, Nagaland

Logging in the forests is a significant activity that leads to forest degradation or complete deforestation. Logging began in India when the British first began to cut and use forest timber for railroads, shipyards, and profit, and after independence, the activity assumed even greater aggressiveness as industries, urban markets and other avenues expanded. Generally, the government sells the forests on stump through public auction to contractors. The assortments produced can be broadly classified into three categories - commercial timber used primarily for building construction, railway sleepers, poles & fence posts; industrial wood used mainly for making boards, plywood, veneers, furniture, packing cases and raw material for pulp; and fuelwood. In 2014, timber industry of India produced almost 50 million cu. m. of logs. There appears to be no estimate available on how much degradation of natural forests is linked to logging. Apart from government auction, organized illegal logging has also become commonplace, and according to government sources from 2009, 2 million cu. m. of logs were being illegally felled each year. In the North-Eastern Region, logging is a common sight, both legal and illegal practices being rampant. According to one recent report, in Nagaland, logging has been one major reason causing loss of over 70% forest cover. Mountain after mountain in Nagaland reveal denuded slopes and timber mills, one of which is shown in the photo above. A good number of these mills are illegal. It is estimated that about 392,000 metric tons of timber is transported out of Nagaland while another large quantity is used up within the State itself.

Use of timber as domestic fuel in West Siyang district, Arunachal Pradesh

India is the world's largest consumer of fuelwood and the country’s fuel wood harvest is estimated to total 300 million cu. m. per year. It is contended that the country¿s fuelwood consumption is already five times higher than what can be sustainably removed from forests. Fuelwood meets about 40% of the energy needs of the country. About 70% of the fuelwood obtained from forests is used by households while the remaining is consumed by commercial and industrial units. It is estimated that around 80% of rural and 48% of urban residents use firewood. In the North–Eastern Region in general and in Arunachal Pradesh in particular, firewood is the chief source of domestic fuel. It is a common sight to see houses having tons of dried wooden logs stacked for the purpose.

Forests being burnt for creating agricultural fields under shifting (jhum) cultivation in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

A significant fraction of deforestation in India is caused by the practice of shifting cultivation, also known as ‘slash-and-burn’ cultivation. Known by different names, it is practiced in the States of Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram and Tripura in the North-East, and also in Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. In the North-East, the practice is commonly called jhum and affects large areas. In this method, forests are first cut down, allowed to dry up and finally set on fire as shown in the photo above. An agricultural field so prepared is sown with crops successively for 2-3 years until the soil fertility declines, and then the farmer moves to a new patch. Though wood ash is an organic fertilizer, providing phosphorous, potassium, calcium, boron and other elements that growing plants need, besides also being alkaline, the practice in the current form and intensity is causing massive degradation of nature and hence affecting the water cycle and water resources. While earlier a used agricultural patch was allowed a regeneration period of 10-15 years, under rising population pressure, the jhuming cycle has been shortened to barely 4-5 years. Consequently, large patches of denuded lands on the hill slopes are becoming a common sight in these States, with serious impact on local water resources. Moreover, burning contributes to warming, further impinging upon the water cycle. In Nagaland, over 80% farmers practice jhum and over 40% of the geographical area is subject to this form of cultivation. Out of a total area of 7,000 sq. km. under jhum in the State, around 500 sq. km. is cleared of vegetation and burned annually for creation of agricultural fields. During the period 2015-2017, a decrease of 450 sq. km. of forest land has been recorded, attributed primarily to jhum.

Terrace fields in Tehri-Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

Clearing of forest lands for agricultural expansion has been an age-old practice in India, intensifying with increase in the population and food demand (local as well as global). According to historical studies on land use in the country, cropland area has increased from 920,000 sq. km. to more than 1,400,000 sq. km. during the period 1880–2010. Greater cropland expansion occurred during the period 1950–1980s that coincided with the period of farm mechanization, electrification, and introduction of high yielding crop varieties under the ‘Green Revolution’. It is obvious that cropland expansion has been possible through clearing of pristine forests and encroachment of forest land continues unabated during present times. While in the Plain areas, permanent agricultural fields have been created, on the gently sloping hills, terraces have been developed for cultivation of different kinds of crops. In the Himalayan State of Uttarakhand, majority of the districts are hilly, lying within an altitudinal ranging from 200 m to more than 8000 m above mean sea level. Consequently, in this primarily agricultural State, human habitation has been made possible only by creating terrace fields on the previously forested hillslopes. These terraces are used for growing both Rabi crops like wheat and barley and Kharif like paddy, small millets and potato.

A tea plantation in Darjeeling district, West Bengal

Rising demand for tea, coffee, and rubber is translating into expanding plantations for these crops across the country. India is the largest producer of black tea as well as the largest consumer of tea in the world. Currently, India produces 23% of total world production and nearly 80% of it is consumed within India. In terms of area under tea production, India ranks second in the world, the area being 5,800 sq. km. In the early 1820s, the British East India Company began large-scale production of tea in Assam, and over time it has expanded to: West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Sikkim, Nagaland, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Bihar and Orissa. In the Darjeeling hills of West Bengal there are 87 tea estates covering over 175 sq. km. of land, and producing over 9 million kg of tea per year. Coffee production has similarly flourished in India in the hill tracts of the South Indian states, particularly Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, along with new areas in Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, and the Northeastern states. The total area under coffee production is estimated to be more than 3,470 sq. km. Rubber as well as timber plantations are similarly being expanded. All these different kinds of commercial plantations are developed after cutting down the natural forests and despite the long-term green cover they ostensibly create, these cannot replace the natural forests and therefore make serious impacts upon the water cycle. Moreover, use of agrochemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides further degrade the ground and surface water quality.

The Tehri Dam in Tehri-Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

Dams and reservoirs are another important driver leading to degradation of nature in India through significant changes in landscape, accompanied by deforestation. There exist 59 'large dams', with height 100 m and above or with storage capacity of 1 cu. km. and above, covering a total reservoir area of about 12,728 sq. km. There exist several hundred more dams and reservoirs of smaller capacities, all constructed for purposes like hydropower, irrigation, water supply, flood control, and navigation. The massive area under these constructions has undoubtedly submerged vast stretches of forested lands. According to recent data from government of India, during the last three decades, 1,351 sq. km. forest land has been diverted for hydel projects alone. Tehri Dam, shown in the above photo, is the highest dam in India and the eighth highest in the world. Located on the Bhagirathi River in the Himalayas, this multi-purpose dam which is part of the Tehri Hydroelectric Complex, is planned to generate 1,000 megawatts of hydroelectricity through 14 projects. The construction of this dam involved submergence of 109 villages (full or partial) and original Tehri town (full), and diversion of over 42 sq. km. of pristine Himalayan forests. Moreover, for the purpose of hydropower generation, the original river bed has been dried out at places and the water is instead diverted through tunnels. As a result of deforestation, changes in topography and altered land use in the mountains emanating from these constructions and diversions, local ecologies and livelihoods stand seriously affected, and Himalayan villages are unbelievingly beginning to face situations of drought.

The new Tehri settlement (New Tehri town) in Tehri-Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

Urbanization is another important factor leading to deforestation and landscape changes in India, converting natural environment into ‘built’ environment. According to historical studies on land use change patterns in the country, the rate of urbanization has been significantly faster after the 1950s due to rapid increase in population and economic growth, being most conspicuous in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. A total of about 1,200 sq. km. of the forest areas is estimated to have been cleared for urban development in the country during the period 1880–2010. Presently there exist more than 35 cities having million-plus population, with Delhi (having over 22.7 million residents), Mumbai and Kolkata as the world’s second, seventh and tenth most populous urban agglomerations. Expansion of these cities and many others have taken much toll on the local forests and natural landcapes, besides placing immense pressure on natural resources drawn from local hinterlands and elsewhere. For example, a substantial part of the water demand in Delhi is met from water stored in the Tehri Dam. The new Tehri town itself is a glaring example of the extent of natural degradation resulting from fresh urbanization, as shown in the photo above. The original Tehri town - the administrative headquarter of the district - was submerged under the Tehri dam and a new town – called New Tehri - has been constructed about 16 km away from its predecessor by cutting down forests and changing the natural Himalayan landscape in a massive way. The new town is larger, has many modern facilities and is foreseen to become an important tourist location in the state.

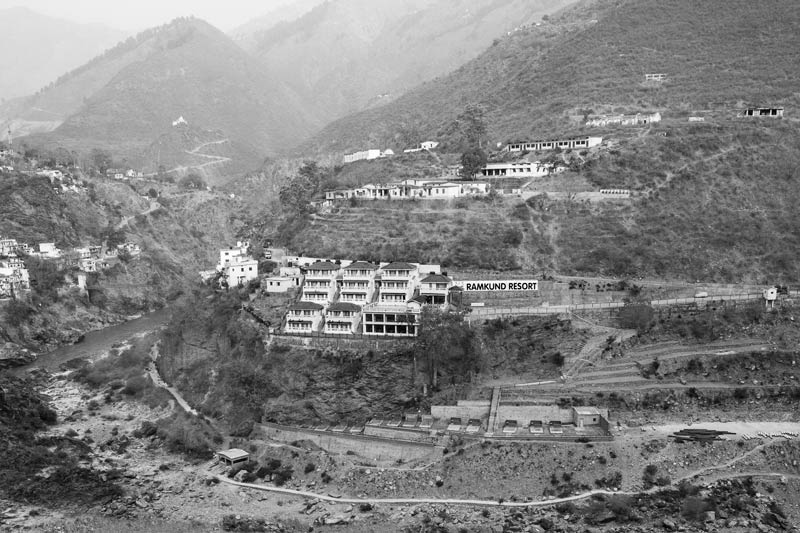

New resort construction for boosting tourism in the Himalayas at Devaprayag in Tehri-Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

In recent years, there has been increasing emphasis on tourism development as an economic sector in India, particularly in areas where tourists can appreciate the natural as well as local cultural environments. Places like the Himalayan Region, North-East India, Kerala, Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep Islands are some of the areas being developed as nature-based tourism hotspots. Though tourism development is argued to contribute to increased incomes and living standards, transport facilities, improved trade, as well as opportunities for cultural exchange, serious doubts have been raised over conservation of nature, local environment and culture. In the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, religious tourism is also an important segment being developed alongside nature-based tourism, but the environmental cost of such economic development is tremendous. This is sufficiently indicated in the above photo where new tourist resorts are being constructed after removal of the natural forest cover and changing of the landscape. This is already adversely affecting the water cycle and influx of tourists in the future can be foreseen to further deepen the ecological crisis by increasing the demand on the already scarce natural resources (like water) and enhancing pollution.

A sandstone quarry in Jodhpur district, Rajasthan

The stone industry is an important economic sector in India, employing over 2 million people. Important stone varieties that are architecturally important and widely used in the construction industry include granite, marble, sandstone, limestone, slate, and quartzite. India has major resources of these stones with an estimated resource of about 1,690 million cu. m., and these are consumed within the country as well as exported. Commercially viable rock deposits exist in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana, and others. Despite their economic value, the impact of stone quarrying on nature is deplorable, including loss of forest cover; damage to landscapes; damage to canals, streams and other surface water bodies; damage to underground aquifers; and deterioration in water quality. Rajasthan is endowed with large reserves of commercially important stones, particularly marble, sandstone and limestone. Jodhpur is well-known for producing sandstone which is used extensively in Rajasthan and Northern India and even exported to Canada, Japan, and the Middle-East. Studies indicate that the area under sandstone mining in the district is around 17.35 sq. km. and there exist 69 open cast mines. In the last two decades, sandstone mining has caused much damage to water mainly through mutilation and blocking of 27.4 km of natural drainage and paralyzing of 50% of the Main Keru Canal and other major canals like the Chota Abu, Kaliberi and Nadelao, all connected to Kailana-Takhatsagar, the largest city lake in Jodhpur city. Also, extensive quarrying has caused reduction of water flow to existing lakes in the city.

Lime factory near Cherrapunji (Sohra) in East Khasi Hills district, Meghalaya

Industrialization is yet another important driver of deforestation and landscape degradation. A number of industrial townships and complexes have been set up in different parts of the country for economic development. Many of these have been established after clearing pristine forests, particularly in areas supplying necessary raw materials for the industrial processes. Limestone is one such mineral which has led to deforestation not only for its mining but also for setting up industries using this mineral. Meghalaya in the North–Eastern Region is abundantly blessed with limestone, possessing about 9% of the country's reserves. Limestone mining is carried out by open cast method, and it is primarily used for manufacturing of cement, edible lime and lime. The latter has several uses in building construction and maintenance, iron and steel industries, foundries, and in drugs, paper and pharmaceuticals industries. 68% of the limestone mined in Meghalaya is used by cement industries and the remaining 32% by lime manufacturers. A local factory manufacturing lime is depicted in the photo above, demonstrating the extent of environmental destruction resulting from this industry. Lime and cement industries abound in the State, and limestone mining and cement plants in the region are seen to have aggravated water scarcity as well as water pollution in the area.

The lost glacier - site depicting past location of Gaumukh, the snout of Gangotri glacier, in 1966 as inscribed on one of the stones here by Government of India in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

Deforestation has affected the water cycle in many ways, and one of the pathways is atmospheric warming which is leading to accelerated glacial melt in the Himalayas. Gaumukh, the snout of the Gangotri glacier, has retreated by about five km from Bhojbasa. Bhojbasa, at an altitude of 3792m above mean sea level, is named after birch (Bhojpatra) forests in the area. However, presently it has become totally denuded of the birch trees. The photo shown above depicts an area located about 4.5 km from Bhojbasa and from this location Gaumukh has further retreated one km to its present location. According to scientists at the National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee, the glacier is in retreat because the rate of glacial melting is faster than its recharge. The disappearance of the natural birch forests in the region have caused disappearance of the carbon sink, and hence warmer temperatures. This in turn causes more rainfall than snowfall, both of which have warming effect on the glacier. Consequently, less ice is forming to replace the melting ice every year.

Changing shape of Gaumukh - the snout of Gangotri glacier in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

It has also been observed that the shape of the snout of Gangotri is also undergoing change under the influence of melting. Earlier it appeared as a convex shape structure protruding outwards, and hence the name ‘Gaumukh’ – mouth of the cow. However, in recent years, it appears to be caving in and is concave in shape as shown in the above photo.

Nearly dry bed of river Bhagirathi in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

As a result of drastic landscape changes, water bodies get significantly impacted. The Tehri dam and the associated hydel projects are a glaring example. As explained earlier, as a part of this project, the natural course of river Bhagirathi has come to be artificially diverted. The river water has been tunneled through a distance of 52 km while a stretch of about 114 km of the original riverbed has become nearly dry as shown in the photo above. Such tampering of natural water bodies destroys aquatic ecosystems and robs the ecosystem of its water wealth, in turn adversely impacting the flora, fauna and human communities dependent on it. The different components of the water cycle - surface water bodies, groundwater aquifers and ‘green’ water existing as soil moisture are not discrete units but constitute parts of a unified system. Disappearance of surface water bodies reduces soil moisture and groundwater recharge, ultimately leading to drying up of local drinking water sources and drought-like conditions adversely affecting agriculture, reported to be increasingly experienced by the local communities in recent times.

Hardships caused by drying up of local drinking water sources called gadera in district Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand

Events like drying of river or depletion of groundwater resulting from landscape changes and deforestation can have serious implications for drinking water sources of local communities. In the hills of Uttarakhand, tunneling of Bhagirathi river’s water together with other landscape changes related to the Tehri Dam project (including large-scale deforestation) have taken a toll on the water resources. The mountain springs which feed the major source of drinking water in the villages - called ‘gadera’ - do not get adequately recharged any more, and dry up soon after the monsoon season. Drying up of the gadera nearest the village settlement forces women and girls, who are the primary domestic water managers, to travel long distances in search of water - in this case more than 2 km - causing immense hardships and even threat to life on the steep mountainous terrains, as evident from the photo above.

Scooping out scanty drinking water from a spring-fed tank in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

Mountain ecosystems are highly sensitive to changes in the water cycle triggered by deforestation and landscape changes. The water resources in the North-Eastern Hill Region have responded intensely to these changes, very similar to that observed in Uttarakhand. Following the impact pathways described earlier, seasonality of drinking water sources has emerged as a serious problem in this Region. In the Nagaland villages, the problem is acute since Naga villages are mostly located on hilltops. Soon after the monsoon, the springs and tanks fed by the underground springs in or near the village settlements start drying up, forcing women, men and children to scoop-out the scanty water that recharges slowly, as shown in the above photo. This activity additionally poses quality challenges due to risks of microbial and physical contamination. Later in the dry season, people are forced to search for water from more distant sources located down the hill, exposing them to greater hardships and risks on the steep hills.

Small tankers supplying drinking water during the dry season in Dhanbad, Jharkhand

As noted earlier, mining causes deforestation, landscape changes as well as loss of naturally occurring water resources through dewatering. Cumulatively, these deeply impact the water availability to local communities in and near the mining areas. According to a Central Ground Water Board assessment, in the Jharia Coal Field area, the groundwater is already 'over-exploited' while in the nearby Dhanbad town it is in a 'critical' stage, signifying groundwater usage more than 100% and 90-100% respectively. Water supply in the town was earlier dependent on groundwater, but due to the rapidly receding water tables caused by mining, only about half the water demand could be met. Consequently, for meeting this deficit, water was diverted from the Maithon Dam on river Barakar. However, even the dam doesn't have enough water for meeting the town's demand because of lesser rains resulting from deforestation in the area. This leads to continuation of water scarcity in Dhanbad especially during the dry season, as portrayed in the photo above.

Poor yield of wheat crop due to insufficient rains in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

The impact of deforestation and landscape changes on local water resources further affects livelihoods of communities, particularly agriculture and animal husbandry. Insufficient rains reduce water availability for irrigation systems, whether based on surface reservoirs or groundwater. In case of rainfed agriculture, deforestation and landscape change not only impact through delayed or insufficient rains, but also through reduction in the naturally occurring soil moisture. In the Himalayan State of Uttarakhand, where agriculture is the economic mainstay, large-scale deforestation and landscape changes have brought drought-like situation in the area in recent years. The situation was so severe in 2016 that over 740 sq. km. of agricultural land in the state were officially declared as drought-hit due to reduction in post-monsoon rainfall by 50%. The drought affectied the yield of rabi (winter) crops, namely mustard, lentil, wheat and commercial fruits such as apple. In case of wheat, the poor yield resulting from insufficient irrigation due to failure of winter rains is depicted in the photo above. Reduced soil moisture and failing of winter rains also degrade the pasturelands, affecting animal stocks reared in the local communities.

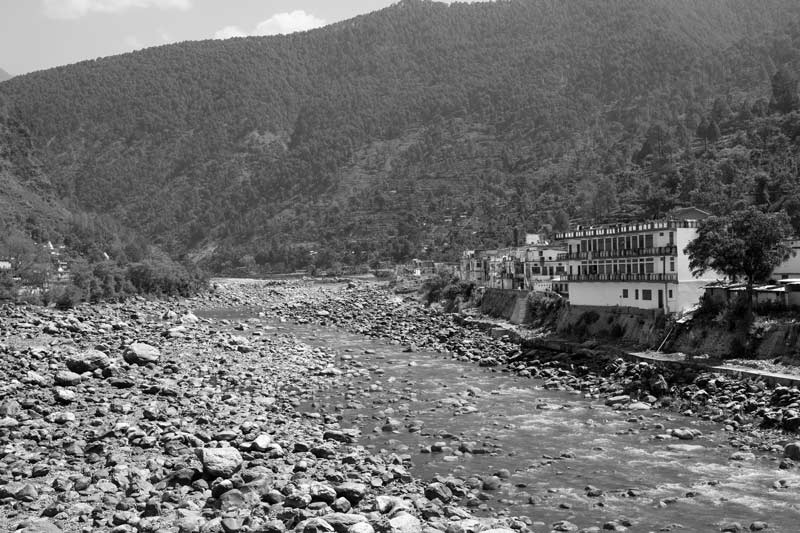

Muddy water of river Alakananda meeting clear bluish-green water of Bhagirathi at their confluence in Devaprayag, district Tehri-Garhwal, Uttarakhand

An important impact of dam construction on river courses is increased silt transportation to rivers and the consequent silting of the river bed and the connected dam. Silting in river Alakananda is an important outfall of the construction of the several hydro-electric power projects on it. Seven projects have been completed, eight are under-construction while 23 more are proposed. Deforestation and rapid landscape changes in the process of construction have increased soil erosion and landslides, because removal of vegetation loosens up the soil. This increases the transport of sediments into the river stream. In the above photo, the silt-laden muddy water of river Alakananda can be clearly distinguished from the clear bluish-green water of Bhagirathi at their confluence with the mythological river Saraswati (flowing underground) in Devaprayag. It is obvious that the silt load carried from upstream will be deposited downstream causing riverbed rise all along the course, which in turn is an important cause of floods.

Village Kalyanpur submerged under flood in Munger district, Bihar

Deforestation and landscape change are important drivers of flood. Removal of forests reduces water holding capacity of the soil. These changes also open up top soil layers, enabling easy transport of sediments from land into the river course during events of precipitation. This results in rise of the river bed and consequent decrease in water holding capacity of the river. As a cumulative consequence, in the event of rainfall, especially intense spells, the volumes of rainwater draining into rivers and streams become large, which cannot be contained within the river bed any more, thus causing floods. Floods lead to submergence of human habitations, including drinking water sources and sanitation facilities. This jeopardizes people’s access to safe drinking water and sanitation, and the resultant water pollution enhances risk of epidemics such as cholera and diarrhea. A number of flooding events have occurred in India during the recent decades. Bihar is the most flood-prone State of the country, where 16.5% of the total flood affected area is located. However, the floods in Bihar are not primarily caused by local extreme rainfall events, as is evident from the 2013 flood shown in the above photo. Due to continuous heavy monsoon rainfall in northern part of the country, river Ganga and its tributaries brought floods to 20 districts in Bihar from the deforested catchments upstream. What is noteworthy is that during this period, many of these districts of Bihar were actually reeling under drought with significant rainfall deficit due to delayed monsoon. The flood caused a huge loss in the terms of life and property in Bihar, affecting more than 5.9 million people in 3,768 villages.

This photo story paints a vivid picture of how nature has come to be progressively degraded in India for fulfilling the need and greed of humankind, through large-scale deforestation and massive landscape changes. The impact of the degradation of nature on water is more than evident and is multi-faceted. The climate has become warmer and the water cycle has been seriously affected, leading to multiple effects. There are changes in precipitation patterns, drying up of surface water bodies, insufficient recharge of groundwater aquifers, silting of surface water bodies, and also floods. Since water is a central resource enabling life, these impacts on water have serious consequences for thriving of flora and fauna and development and well-being of human populations dependent on it. The effect of deforestation and landscape changes on the water resources in turn impacts the natural environment and thwarts access to drinking water and water availability for livelihood activities in the local communities. The drying up of drinking water sources in or near settlements forces women and girls to travel longer distances across difficult terrains in search of water. Reduced soil moisture and water availability for irrigation leads to reduced crop yields and hence lowered incomes. Pasture lands for sustaining animal stocks get shrunken, and floods and droughts become more common. Even communities located far downstream may get affected by floods due to changed rainfall patterns and degraded landscapes upstream. Destruction of nature thus seriously thwarts all the three pillars of sustainable development – environmental, economic and social - and impedes the enjoyment of human right to water and the concomitant rights such as health, education, livelihood and development. There is need to seriously evaluate the consequences of every act of degradation of nature from water perspective and initiate appropriate action. Otherwise, as this photo story has revealed, it would become impossible to reach the Sustainable Development Goals and enable women, men and children to enjoy their human rights.