Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and EnvironmentA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2017

Government Response to Wastewater Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

18 April, 2017

Huge volumes of wastewater are generated in India everyday from diverse sources primarily municipal, industrial and agricultural. Without appropriate treatment, the contaminants present in the wastewater pollute freshwater resources, affect the soil and degrade the environment. This in turn thwarts enjoyment of human rights by women, men and children and bring negative implications for sustainable development. Glimpses of these challenges have been presented in the photo story titled "Problems of Wastewater: An Overview" dated 20 March, 2017. Considering the gravity of these challenges, and recognizing its responsibility towards safeguarding the basic human rights obligations and promoting sustainable development, the government at national, state and local levels has initiated a number of actions to address the challenges. In order to reduce the pollution load from municipal wastewater, 920 Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) have been installed in cities and towns with a total treatment capacity of 23,277 MLD. However, according to Census 2011, India has 7935 cities and towns and these generate over 61,948 Million Litres per Day (MLD). This latter figure is also a gross underestimation because the sewage generated from groundwater extracted at individual household level or procured from sources such as tankers remain unreported. According to government's industrial census of 2011-2012, there exist more than 11.5 million micro, small and medium enterprises that are engaged in the manufacturing sector. These include many industries that produce toxic wastewater such as leather tanning, textile manufacturing, fabric dyeing, and pharmaceuticals. While the government has implemented the scheme of Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) for industrial clusters of small-scale industry, these number only 193 with a combined capacity of merely 1474 MLD, being scattered in 2900 industrial areas in the country. This again is highly inadequate. Regarding agricultural wastewater that contain chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides, there exist neither estimates of the volumes generated, nor any control over the pollution of freshwater bodies that they cause. The above figures present a worrisome picture and more than underline the deficiencies in the current government response to wastewater challenges in the country. 48 river stretches in the Ganga basin are already polluted, as are another 254 stretches in other river basins. This photo story presents critical reflections over the nature, extent and effectiveness of the governmental efforts at addressing the wastewater challenges in India. The title photo depicts an aeration tank at the CETP in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Sewage pumping station at Jalasen Ghat on the bank of river Ganga in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Ganga is world's fifth most polluted river and for controlling its pollution, the government has launched 3 different interventions since 1986, namely the Ganga Action Plan, Mission Clean Ganga 2020, and very recently Namami Gange. In order to control pollution of the river at Varanasi, where municipal sewage is identified as the main source, 3 STPs have been installed by the government at Dinapur, Bhagwanpur and Diesel Locomotive Works. The total capacity of these plants is around 100 MLD. These STPs are supposed to receive the sewage through five sewage pumping stations located along the ghats, and one main sewage pumping station at Konia. However, these pumping stations rarely work at full capacity, the single main cause being inadequate power supply. As a result, the sewerage infrastructure operates intermittently, defeating the very purpose of the intervention.

Untreated sewage being diverted into river Ganga near Mansarovar Sewage Pumping Station in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Since the sewage pumping stations operate intermittently because of power shortage, while sewage is generated in the city round the clock, a large amount of the sewage cannot be transported to the STPs. This happens despite the fact that the pumping stations are equipped with generators, and even these often remain inoperational. As a result, the raw sewage is diverted through drains such as the one shown in this photo, and emptied directly into river Ganga. In the event of continuation of such irresponsible actions, construction of STPs to keep the Ganga clean is no more than paying mere lip service to the ongoing efforts.

Untreated sewage being discharged into river Ganga through the Khirki Drain in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Varanasi generates over 250 MLD sewage, out of which about 150 MLD is directly discharged into river Ganga through several drains, of which the Khirki drain is one. Scientific analysis of water quality of the river in the city for last 22 years indicates that the water quality of the river along its religious bathing ghats has been continuously deteriorating. For water to be safe for bathing the faecal coliform count (FCC) should be less than 500/100ml and Bio-chemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) should be less than 3 mg/litre. Similarly, the dissolved oxygen (DO) should not be less than 5 mg/litre. However, studies at Khirki drain show that the FCC is 80,00,000 /100ml, while the BOD level is 58mg/litre and DO level is 1.6mg/litre. It is indeed a dismal situation despite the multiple government efforts to clean river Ganga.

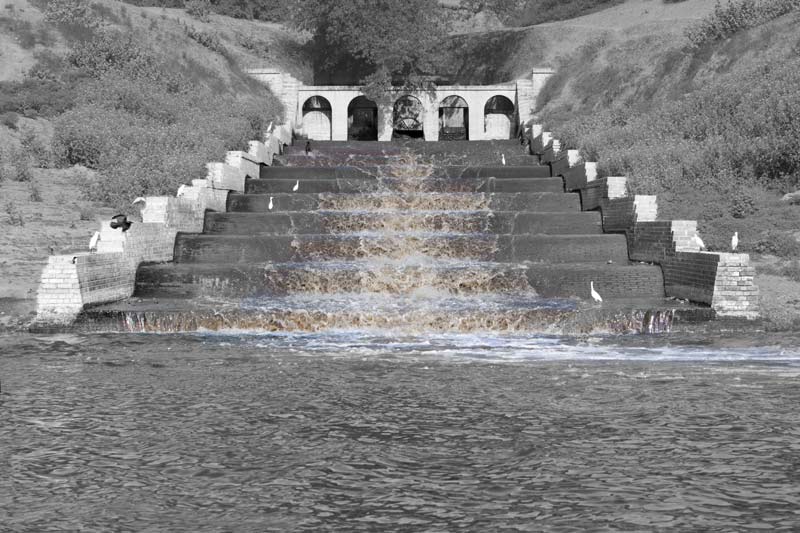

The Hebbal STP near Hebbal Lake in Bengaluru, Karnataka

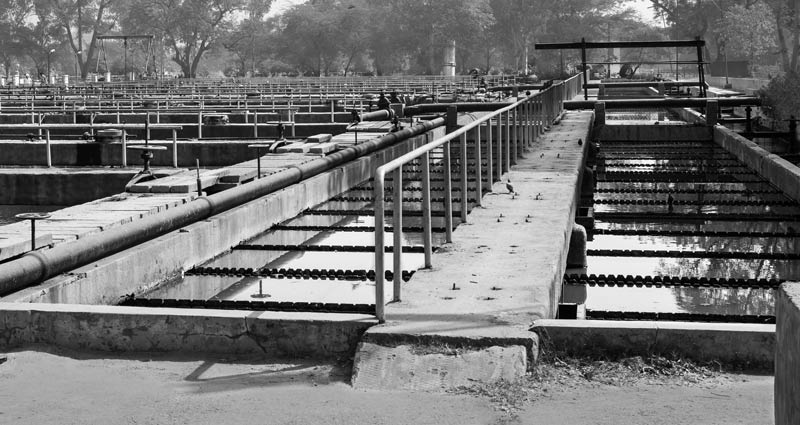

Bengaluru, the capital of Karnataka, is the third largest city and the fifth largest metropolitan area in India according to the 2011 Census. One of the fastest growing metropolitan cities, its population is about 8.5 million, which is estimated to generate about 1400 million litres of sewage per day. The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) is responsible for collecting, conveying and treating the wastewater generated in the city through 14 STPs which have an aggregate capacity of treating 721 MLD wastewater. It is obvious that only about half of the city's sewage has the potential of being treated, while the rest is dumped directly into its rivers and lakes. Thousands of new apartment buildings located in the new residential layouts discharge their wastewater into storm water drains which finally empty into nearby lakes and rivers, causing large-scale pollution of surface as well as groundwater resources. Moreover, due to various reasons such as ageing of sewers and damages in the sewerage system, even the existing potential of STPs remains underutilized, with an average total treatment of only about 520 MLD. The Hebbal STP located near Hebbal and Nagavara Lakes, having a treatment capacity of 60 MLD, is the fourth largest STP in the city but remains underutilized.

An inlet draining sewage into Hebbal Lake in Bengaluru, Karnataka

Despite the presence of a STP near Hebbal Lake, pollution of this water body has been a major concern in recent years, as is the situation in many other lakes in Bengaluru. In order to reduce the pollution load in the lake, Hebbal STP Zero Flow Scheme has been implemented by the BWSSB: In this scheme 18 Kms of trunk sewers were rehabilitated at a cost of Rupees 450 million (approx. 7 million USD) with the expected benefits that there would be zero sewage flow in the storm water drains and therefore no entry of sewage into Hebbal and Nagavara Lakes. However, despite the implementation of the scheme, the inlet shown in the photo continues to discharge sewage into Hebbal Lake, verified by the eutrophication and the foul stench which pollutes the air around.

Sewage being pumped to a STP in East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

The Okhla STP in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Delhi, the capital of India, is the second largest city and metropolitan area in India according to the 2011 Census. Its population of over 16 million generates about 3267 MLD of wastewater. In order to treat this wastewater, 36 STPs have been installed at 21 locations. However, according to a report from Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), out of the total sewage generated, treatment capacity exists for only about 71%, and actual treatment is given to only about 45% of total sewage generated. Many of the STPs in the city have been reported as running under-capacity, or even being non-functional. As a result, untreated sewage gets discharged directly into river Yamuna, converting it into a sewage drain in Delhi.

Common Chrome Recovery Plant (CCRP) in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

In Kanpur a large number of leather tanneries are located in Jajmau industrial area, right along the banks of river Ganga. These units use many toxic chemicals, chrome being an important tanning agent which is highly polluting for surface and groundwater resources. In order to address this challenge, provisions of the Charter on "Corporate Responsibility for Environmental Protection (CREP)" launched by the Ministry of Environment & Forest (MoEF) have been applied to Jajmau. Among the action points enlisted for the tannery sector in the Charter is the requirement for these units to have "Chrome Recovery Plant" either on individual basis or on collective basis in the form of Common Chrome Recovery Plant (CCRP) and use the recovered chrome in the tanning process. A CCRP has been installed in Jajmau with over 80 member tanneries and a capacity of processing 70 kiloliters per day.

Chromium recovered from spent chrome liquor at the Common Chrome Recovery Plant in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

Tanning one ton of hide typically results in 20-80 cubic meters of wastewater with chromium concentrations around 250 mg/L which can be recovered and conveniently reused. However, the CCRP at Jajmau remains underutilized, with little chrome recovery. There is inadequate participation on part of the member tanneries which refrain from proper segregation, collection and transportation of the spent chrome liquor to the CCRP, but the responsible governmental agencies exercise little monitoring over the situation. Even very few individual chrome recovery plants installed in 118 tanning units perform efficiently, but governmental supervision is poor. This leads to high chromium concentrations in the effluent emerging from the chrome-based tanning units.

UASB Reactor and Collection Well at the CETP in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

In industrial clusters having a good number of small-scale manufacturing units, the scheme of CETP has been launched by the government. The large-scale units are required to have their own effluent treatment plant (ETPs). For the tannery sector in Jajmau, a CETP has been established in Wazidpur village, based on the "upflow anaerobic sludge blanket" (UASB) process. Here due to high sulphate ion concentration in the tannery wastewater, the incoming effluent is diluted with municipal wastewater mixed in the ratio 1:3. The UASB technology was preferred over other technologies commonly used in India on grounds of higher energy-efficiency and cheaper operation and maintenance costs. However, one of the two UASB reactors at Jajmau has been out of order since long. This leads to underperformance of the CETP and consequently, a substantial volume of the received effluent is directly discharged into river Ganga without any treatment. Moreover, the CETP at Jajmau was installed in 1994 to treat only 9 MLD effluent from 175 tanneries, but today their number is over 400, producing about 50 MLD effluent. According to a very recent report from CPCB, this additional 4/5th tannery effluent gets directly discharged into river Ganga without any treatment. Further, the CETP is designed to receive effluent that contains chromium at a maximum concentration of 2mg/L, but actually it contains chromium over 80 mg/L, which does not get substantially reduced even after treatment. This leads to a high chromium level in the treated effluent emerging from the CETP.

Inoperational clariflocculator at the CETP in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

The clariflocculator helps reduce turbidity and remove solids and colloidal material from the wastewater. However, running the clariflocculator requires electricity, and power failures or planned power cuts are common in Kanpur which reduces the efficiency of the process at the CETP. Further, one of the two clariflocculators has been out of order since long, thereby further reducing the efficiency of performance of the CETP.

An effluent treatment plant (ETP) for neutralizing contaminated mine water at Tipong Colliery of Makum Coalfield in Tinsukhia district, Assam

The mining industry in India operates more than 2729 mines which consist of 570 coal mines, 2300 metalliferous mines and other small mines. At collieries and at some other metal mines, the wastewater discharged from the mine contains acid mine drainage (AMD), which is a significant problem. The AMD is highly contaminating for the soil and water resources around, by virtue of containing high concentrations of iron, aluminum, manganese, nickel, lead and cadmium, as well as chromium, copper, zinc and cobalt. Many of these mines, and collieries in particular, are owned and managed by the government. However, unfortunately government's approach towards proper treatment of the mining wastewater before release into the environment has been inadequate. At Tipong Colliery, a small ETP for neutralization of the AMD has been installed. However, this is insufficient because large amounts of mine wastewater are discharged round the year where pumping continues upto two hours at a stretch 4 times a day, and during the rainy season, the discharge continues throughout the day because of seepage of rainwater into the mine. Considering these volumes, the ETP installed at this colliery is nothing more than tokenism, a gesture for just fulfilling the necessary governmental regulations.

Untreated acid mine drainage being released into Tipong river in Makum Coalfield in Tinsukhia district, Assam

Since the ETP at Tipong colliery is small in capacity, and its maintenance and upkeep is poor, untreated mine water is often released directly into the Tipong river nearby, polluting the river water and affecting dependent communities as well as the flora and fauna.

Slurry being transported for disposal from an underground coalmine in Tipong Colliery of Makum Coalfield in Tinsukhia district, Assam

Slurry from an underground coalmine at Tipong Colliery being dumped in open environment in Makum Coalfield in Tinsukhia district, Assam

The slurry resulting from coal mining activity contains high levels of the same contaminants as in AMD, which therefore needs to be disposed safely. However, at Tipong colliery safe disposal of the slurry is not ensured. It is carried away from the mine and dumped directly without any treatment into ditches dug in the ground in open environment nearby. It is more than obvious that the contaminants present in the slurry leach down to groundwater aquifers and also flow down into surface water bodies and agricultural fields nearby. Lands and water resources thus affected suffer from multiple environmental impacts.

This photo story has attempted to present critical reflections upon the governmental efforts at addressing the challenges posed by vast volumes of wastewater generated in India. The basic response has been to treat the wastewater so as to improve its quality before being discharged into surface water bodies. However, the treatment capacity of the STPs and CETPs is very small compared to the amount of wastewater generated. With the current capacity, about two-thirds of the municipal wastewater is directly discharged without treatment into rivers and lakes. A large number of cities and towns do not possess STPs at all and a good number of the installed STPs and their pumping stations either underperform or remain closed, due to frequent power break downs, improper design, poor maintenance, and lack of technical man power. Similarly, the number of CETPs is few, and monitoring over industries that are responsible for removing pollutants from wastewater before discharge has been poor. Even at government-owned industries such as the coal mines which produce highly toxic wastewater, efforts at treatment has been highly inadequate. Consequently, not only is the pollution load in various surface water bodies increasing exponentially, but even groundwater and soils are increasingly affected, ultimately also contaminating the food chain. These negative outcomes of inefficient and inadequate management of wastewater in the country is increasingly jeopardizing the human rights of millions of women, men and children to water, health, livelihoods, culture and development through multiple pathways. It is high time that the governmental agencies – central, state and local - should wake up to the seriousness of the cause and initiate adequate and appropriate measures for wastewater management so that the human rights of millions of citizens can be promoted, environment can be protected and the country can make unhindered progress along the path of sustainable development.