Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and EnvironmentA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2017

Integrated Approach for Encountering Wastewater Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

15 May, 2017

The large amounts of wastewater generated in India present enormous challenges for sustainable development. These also thwart enjoyment of basic human rights by women, men and children. These challenges have been portrayed in the story "Wastewater challenges: An overview" dated 20 March 2017. The government has attempted to address these challenges through a number of significant interventions. However, as the story titled "Government response to wastewater challenges" dated 18 April 2017 illustrates, these responses have not been able to adequately address the challenges. There exist significant gaps in the current government approach and several failures appear on quantitative as well as qualitative fronts. In this light, the pertinent question is: How to appropriately and adequately encounter the challenges posed by the colossal amounts of wastewater generated in India? This photo story delineates an approach for dealing with the problem in an integrated manner. It proposes that multi-pronged efforts on both quantitative and qualitative fronts is urgently required. On the quantitative front, there is need to draw realistic estimations of the wastewater generated from different sources and ensure adequate facilities for their treatment. On the qualitative front, the need is to ensure that the different arrangements in place for recycle of wastewater remain functional at the optimum level. This may require regular monitoring for compliance. Also, qualitatively it is important that interventions be designed and effectively implemented for the hitherto uncovered areas of water use such as animal husbandry and aquaculture that generate significant amounts of wastewater. Also, adoption of decentralized wastewater treatment is proposed. Finally, there is need to generate widespread awareness among all water users – individual and institutional - regarding the consequence of diverse water uses for human and environmental health and to secure the right actions on their behalf. The title photo depicts a sewage treatment plant (STP) on the shores of Hebbal Lake in Bengaluru, Karnataka. The purpose of this STP is to treat the wastewater contained in one of the major stormwater drains before it enters the lake.

The STP at Dinapur near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

At Varanasi, the Holy City on the banks of river Ganga, there are three STPs of which the one at Dinapur is the largest with a treatment capacity of 80 million liters per day (MLD). According to a latest report from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), the total sewage generation in the city is estimated to be more than 400 MLD while treatment capacity exists for only about 100 MLD. This implies that around 3/4th of the city's sewage is disposed untreated into the river. In the Ganga basin as a whole, the total wastewater generated in 222 towns is 8,250 MLD, but the treatment capacity exists for only about 3,500 MLD. According to the CPCB, the estimated sewage generation in the country in 2015 was 61,948 MLD against available treatment capacity of only 23,277 MLD. The country's 7935 cities and towns have only 920 STPs for the treatment of their municipal sewage. In order to address the wastewater challenges in Ganga basin, other river basins and the country as a whole, there is an urgent need to bridge the current gap in treatment capacities which is enormous as the figures above illustrate.

A sewage pumping station at Dr. Rajendra Prasad Ghat on the bank of river Ganga in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

At Varanasi, the existing wastewater management facilities include three STPs and six sewage pumping stations. The function of the sewage pumping stations is to divert the sewage received from the city to the STPs for treatment. However, the pumping stations either remain inoperational or rarely work to their full capacity. According to one estimate, their efficiency is perhaps never over one-third. Similarly, the STPs fail to work to their full capacity. As a result of inoperational or under-performing sewage management facilities, untreated wastewater gets directly discharged into the river. This is true not only at Varanasi but all across the country, technical well-being of the machinery as well as power supply being the main considerations. If the wastewater challenges are to be addressed adequately, there is an urgent need to safeguard the health of the sewage treatment facilities and ensure uninterrupted power supply to run the operations efficiently.

A septic tank being manually emptied out in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh

In many urban colonies, sewerage network is not available and house-owners have to arrange for their sewage disposal on their own. The most common practice is to construct septic tanks for holding the wastewater containing the excreta from the toilets. However, depending on the capacity of the tank and the number of users of the toilet, the tank needs to be emptied at regular intervals. In colonies with narrow lanes, tractors fitted with large sanitation tankers cannot enter and instead the cleaning is undertaken by manual scavengers. While this practice in itself is highly dehumanizing, the environmental impact of the same is also alarming. Despite the parliament enacting a legislation to prohibit manual scavenging, government data indicates that there are more than 11,000 manual scavengers in the country distributed in 11 states. 86% of these are in Uttar Pradesh alone. They are engaged in manually cleaning dry toilets or in clearing septic tanks manually as shown in these photos.

Raw sewage water from septic tank being disposed into stormwater drain outside the house in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh

Since the manual scavengers cleaning the septic tanks do not have the necessary infrastructure to collect the extracted sewage water, they simply dump the raw sewage water into open stormwater drains nearby, in this case just outside the house. The solid waste extracted from the bottom of the tank is just disposed on any neighboring piece of unused land. This causes pollution of the receiving water bodes as well as affected soils. In order to address the environmental challenge posed by manual cleaning of septic tanks in the smaller urban colonies, decentralized STPs may be provided, which may either receive the extracted sewage or else the households be connected to it through sewage pipes.

A sewage tanker emptying into Najafgarh Nala –a stormwater drain - in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Many houses that are located in informal colonies in cities are unconnected to the sewerage system and engage private tankers to collect the sewage from their filled-up septic tanks. Since there is no specific facility for treatment of the sewage so collected, these tankers often empty the contents into stormwater drains, rivers or other surface water bodies, leading to large-scale pollution of not only surface water but also soil and groundwater underneath. This is a problem of enormous scale and there is need to address the challenge posed by this practice. A practical solution is to provide STPs in or near such areas where it should be mandatory for these tankers to transfer the sewage collected for treatment. The treated sewage can be later reused for irrigation or other purposes or else safely released into rivers and lakes.

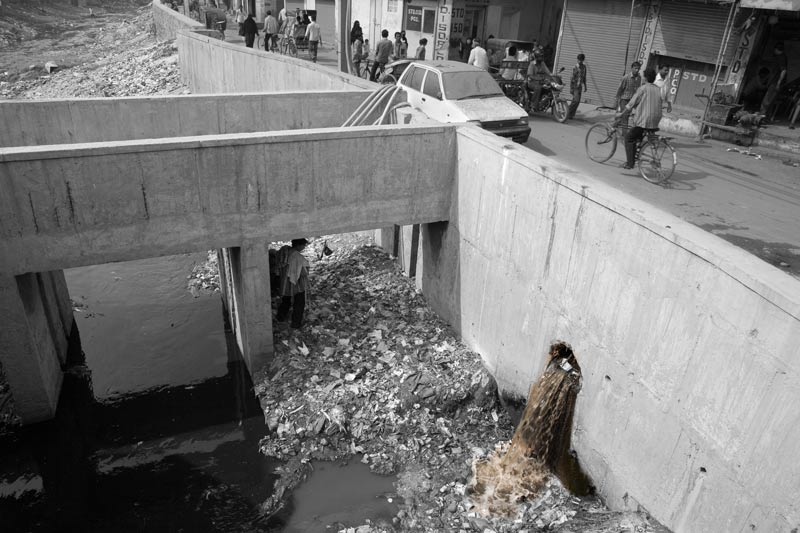

Untreated sewage emptying into a stormwater drain in East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Another important cause of wastewater challenges in India that needs to be essentially addressed is that of stormwater drains turning into wastewater drains in the cities. Due to non-existence of sewage networks especially in the informal settlements, domestic wastewater and sometimes also industrial effluents from small unregistered units are channelized into stormwater drains that ultimately turn rivers and lakes into stinking unhygienic wastewater bodies. The stormwater drain shown in the above photo is laden with raw sewage from the surrounding informal colonies and industrial wastewater from small units around. There is need to prohibit disposal of sewage and effluents directly into stormwater drains by either expanding the sewerage network or by providing for decentralized wastewater treatment facilities at the local scale.

A channel conveying untreated sewage into river Ganga in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Rivers and lakes in the country get polluted by release of untreated domestic and industrial wastewater conveyed through small drains and channels. In Varanasi, areas in the outskirts of the city, those under the process of recent development and many other areas are not provided with sewerage system. According to one estimate, about 70% of the city is unconnected to sewerage network. In these areas, wastewater from individual houses is diverted to nearby open fields, from where it ultimately reaches river Ganga through small drains and channels. While figures for these smaller drains and channels is missing, it is obvious that there is need to implement strict prohibition on such local level disposal of untreated sewage, and instead facilitate the uncovered localities with either sewage connections or else implement schemes for decentralized STPs. Such an intervention is necessary for not only Varanasi but all cities and towns where large areas remain uncovered by sewerage facilities.

Untreated sewage entering Ulsoor Lake from a stormwater drain in Bengaluru, Karnataka

The dumping of untreated sewage into city lakes through stormwater drains is a considerable problem across the length and breadth of the country. Ulsoor — a 124-acre lake in the heart of Bengaluru - is a significant example. This lake was constructed by the family of Kempegowda II in 17th and 18th centuries for drinking and irrigation purposes, but today it cannot even sustain aquatic life. Its two inlets originally designed to recharge the lake with stormwater have now turned into sewage drains due to discharge of untreated sewage into them from the neighboring colonies. Useful solutions for addressing the challenges posed by wastewater discharge into such closed water bodies is to connect the nearby colonies to existing sewerage system or else as already implemented for Hebbal Lake, build a smaller STP next to such lakes so that only treated wastewater is allowed into them. Following these lines, Ulsoor is going to receive its own STP with a capacity of 100,000 litres later this year, which will enable restoration of its water quality and continuation of activities including tourism and recreation through reuse of treated wastewater.

Collection Well at the common effluent treatment plant (CETP) in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

For treating toxic effluents from the tanneries in Kanpur, especially from the medium and small-scale units, a CETP has been established by the government. However, the treatment capacity of this CETP is barely 9 MLD while the current wastewater generation from tanneries has increased to about 50 MLD. In India as a whole, only 193 CETPs have been established, while the number of micro, small and medium enterprises engaged in the manufacturing sector is more than 11.5 million. Many of these produce toxic wastewater. This illustrates the huge gap between the need of CETPs and their availability in the country. Thus the need is to increase the number of CETPs so that the effluent treatment requirements of all small and medium enterprises is fulfilled. Similarly it should be ensured that all large-scale units should have their own effluent treatment plants (ETPs).

Inoperational 'upflow anaerobic sludge blanket' (UASB) reactor at the CETP in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

In order to adequately treat the 9 MLD of tannery effluent received at the Jajmau CETP, there is need for its constituent units to be in good health throughout the year. However, one of the two UASB reactors has been out of order for a long time. This leads to underperformance of the CETP and consequently, a substantial amount of the effluent received remains untreated. This is either supplied directly for irrigation through the Shekhpur Canal or else discharged into river Ganga. Similarly, optimum performance of the constituent units is a pre-requisite for effective treatment of the effluent. However, according to an earlier CPCB study, primary- and secondary-settling units in many CETPs show poor performance which leads to their overall poor performance. Some of the CETPs are also known to be underutilized because either these are not connected to the feeding industries or else the latter do not transport their wastewater to the treatment unit. Similarly ETPs in individual large industries are not maintained in good working condition. The different kinds of problems related to the quality of performance of CETPs and also ETPs needs to be regularly monitored and addressed through appropriate means.

Agricultural fields – a source of wastewater causing eutrophication in Vembanad Lake in Alappuzha district, Kerala

Vembanad is the longest lake in India, 763.23 sq.km. area of which is located 1 metre below mean sea level. Here paddy cultivation is carried out within large blocks of fields or polders called padsekharams, mostly reclaimed from shallow stretches of the lake. Due to the unique positioning of the fields below sea level, unlike ordinary irrigation, that in the padsekharams requires draining out of excess water from the fields into the lake as and when required. In the recent decades, the use of fertilizers and pesticides in the polders has increased, leading to agricultural runoff which is rich in nutrients and chemicals, causing eutrophication of the lake. Leakage of nutrients and chemicals into lakes and rivers through agricultural runoff is a wider problem across the country which often goes neglected in policy and action for addressing wastewater challenges. In closed irrigation systems such as the padasekharams in Vembanad, there is particularly a need to adopt cleaner options like organic farming with minimal external chemical inputs so that the agricultural wastewater can be clean. Otherwise, there is need to establish special treatment plants and connect these to the padasekharams to enable treatment of the agricultural wastewater before it is discharged into the lake.

Dairy farm - an important source for contribution of untreated wastewater into stormwater drain - in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

India holds the world's second largest cattle population and is the largest milk-producing country. The total number of milch cows and buffaloes in the country numbered 118.59 million in 2012, a good number of which is raised in urban dairy farms. In fact, the dairy industry is an important source of livelihood in urban villages. Some of these dairy farms may be very large keeping up to 40-50 cows or buffaloes. Consequently, these generate huge amounts of animal wastewater, but there exist no regulations for addressing the pollution caused by this wastewater. It is drained through local channels into stormwater drains from where it finds its way into local rivers and lakes. The dairy farm shown in the above photo discharges its animal wastewater into Najafgarh drain, which finally empties into river Yamuna. In order to encounter the wastewater challenge caused by the dairy farming sector, there is need to recycle their wastewater. This is possible by either bringing the urban dairy farms under the sewerage network where possible, or else diverting the animal wastewater into STPs that may also cater to the general sewage treatment needs of the locality.

A fish farm that drains wastewater into Kolleru Lake in West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh

Kolleru Lake is one of the largest freshwater lakes in south-eastern India which was an important source of drinking water, agriculture and aquaculture in the region, but today it has become one of the most polluted lakes of the country. A mushrooming of aquaculture farms has occurred in the Kolleru Lake region over the last few decades. Approximately 42% of the 245 sq.km. lake area is occupied by aquaculture, consisting of over 1050 fish ponds. Various chemicals including pesticides such as malathion, chloropyrifos, isodrin and endosulfan are used to control diseases and ectoparasites in these aquaculture farms. The fish ponds are emptied on routine basis and this wastewater drains into Kolleru Lake, adding significantly to the pollution load of the Lake. There is need to take the impact of aquacultural wastewater seriously into consideration and devise appropriate rules, regulations and institutional frameworks to prevent its direct discharge into the lake. There is need to establish special treatment plants and connect these to the fish ponds through a drainage network at the local scale in order to treat the aquacultural wastewater before being released into the Lake.

Houseboat tourism - an important source of untreated wastewater - in Punnamada Lake in Alappuzha district, Kerala

Houseboats are an important component in the tourism industry. In Punnamada Lake, which is the part of Vembanad Lake lying within Alappuzha and Kottayam districts of Kerala, there are more than 1000 houseboats. Of these only about 500 are registered. The Lake is under severe environmental stress due to biological, chemical and physical pollutants, a significant contributor being the untreated sewage from houseboats. While a number of rules and regulations are in place to minimize the ecological impact of houseboat tourism industry in Kerala, both monitoring and compliance are low. For receiving a license to operate a houseboat, provision of bio-toilets and STP on board is essential, but corruption and lack of adequate monitoring make these provisions ineffective. In fact, the environmental compliance need is by-passed by many houseboat owners by operating unregistered boats. In order to realistically minimize wastewater disposal into Punnamada and also in other lakes in the country where houseboat tourism flourishes, there is need to ensure compliance of the existing rules and regulations, through stricter monitoring and implementation.

A holiday resort on an islet in Thathampally Lake in Alappuzha district, Kerala

Hotels and resorts along banks of lakes and other surface water bodies are becoming increasingly common due to their high tourism value. However, the impact of these structures on the local environment in general, and neighboring water resources in particular may be enormous. Hotels and resorts make use of large quantities of water particularly during the tourist seasons, and consequently generate large amounts of wastewater. The law requires hotels located outside cities to have their own STPs for treating their wastewater according to the standard norms. However, in many cases, the wastewater generated in the hotels and resorts is discharged untreated or only partially treated due to inoperational or underperforming STPs, or in some cases, the capacity of the STP itself may be lower than required. There is thus a need to ensure strict compliance of the law by the hotel and tourism industry which in turn requires their regular monitoring by the agencies.

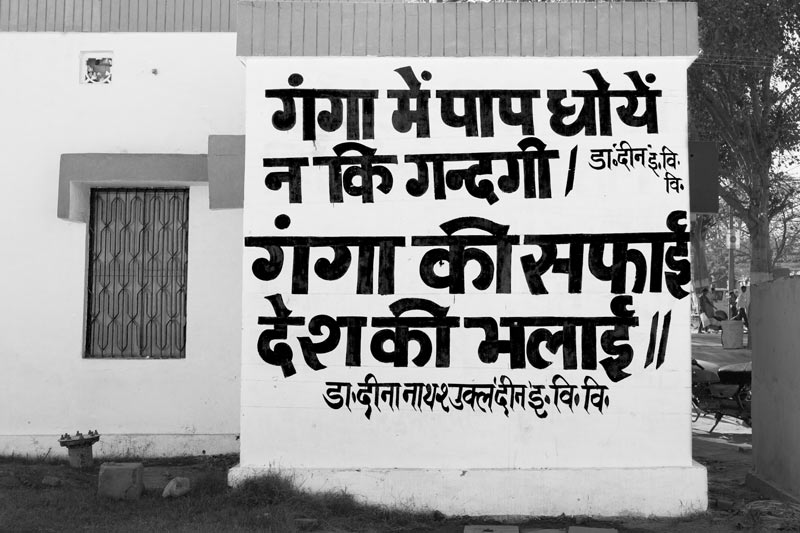

An information, education and communication (IEC) message for public sensitization on keeping river Ganga clean in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh

Raising public awareness about the sources, pathways and impacts of wastewater and sensitizing them towards the practical means of encountering the wastewater challenges is an important dimension. Therefore, IEC campaigns need to be essentially incorporated in any intervention directed at encountering wastewater challenges. These IEC messages written on a house wall in Allahabad, a holy city on the banks of river Ganga, are directed towards the public aiming to bring about attitudinal and behavioral change towards using the river. These convey "Wash your sins in Ganga, not your dirt" and "Cleaning of Ganga is wellbeing of the country".

From the photo story presented above, it clearly emerges that encountering the colossal wastewater challenges in India requires a multi-pronged integrated approach. This integrated approach must combine quantitative with qualitative aspects. Quantitatively the gap between wastewater production and wastewater treatment capacity must be minimized through installation of more treatment plants, while qualitatively the uninterrupted optimum operation of the wastewater treatment facilities must be ensured through improved upkeep and maintenance of the machinery, and uninterrupted supply of essential inputs like power. Besides, there is need to include the hitherto ignored wastewater production sectors and activities, such as agriculture, aquaculture, animal husbandry and disposal of wastewater from septic tanks, into the wastewater recycling plans so as to ensure proper handling of the wastewater. There is need of appropriate polices as well as technical interventions in relation to these contributing sectors. Also, sectors such as tourism need to be tackled with greater caution in terms of more stringent action for compliance. Further required is a decentralized approach where colonies unconnected to sewerage networks are provided with local-level STPs. It is to be noted that Bengaluru has already started with this experiment for its new buildings with 20 or more apartments and the non-governmental organisation (NGO) Sulabh International Social Service Organization runs local STPs at some of its community toilet blocks, from where recycled water for reuse as well as fuel and power are obtained as by-products. Additionally, there is need to immediately restore the health of stormwater drains and prevent entry of untreated wastewater into lakes, rivers and other surface water bodies by extension of the sewerage network or construction of decentralized STPs. Finally, appropriate IEC campaigns must be continuously conducted, because generation of wastewater and its appropriate treatment deal with important attitudinal and behavioral issues. It is proposed that adoption of the above integrated approach would enable encountering the wastewater menace in the country to a considerable extent. This would help protect environmental health and safeguarding the human rights of the citizens, leading the country more efficiently on the path of sustainable development.