Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and EnvironmentA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2018

Protection and Restoration of Nature for Water: Some Observations and Thoughts

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

18 May, 2018

The indispensable role of nature in production, augmentation and conservation of water has been illustrated in the story dated 22 March 2018. Glimpses of how nature is progressively degraded in India in the terrestrial ecosystems through deforestation and change of the natural landscapes and how these changes are impacting water have been presented in the story dated 21 April 2018. Looking at the quantum of damage already caused, it is obvious that if the quantity and quality of water resources is to be protected, restored and sustained, there is need to immediately address the issues of deforestation and landscape degradation in India so that the impact on water can be minimized. While some of the activities like creation of human settlements, agricultural lands, commercial plantations, and industrial development cannot be absolutely done away with, there is need to proceed with extreme caution. For some other activities like mining of valuable minerals and metals, there is need to ensure adoption of mechanisms that would minimize damage to nature. For still some others like hydropower generation, there is possibility of promoting alternatives, while for commercial logging replacement of the lost resources has to be ensured. This photo story aims to portray some observations regarding the mechanisms and initiatives already in place towards this end and present some thoughts on what more is needed to be done so that the degraded nature can be protected and restored, ultimately ensuring that water resources become sustainable. However, what is presented here is not an exhaustive list of existing actions and recommendations, but only a suggestive one. The title photo portrays the balanced ecosystem of the Himalayas with pristine forested mountain slopes and snow-clad peaks ensuring running water in the stream in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand.

Reforestation with Chir Pine on denuded slopes at Chirbasa near Gaumukh in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

One of the positive responses to large-scale deforestation in India has been afforestation and reforestation. According to the India State of Forest Report 2017, due to these measures, forest and tree cover of the country has increased by 8,021 sq. km. (1%) since the previous assessment of 2015. Chirbasa, signifying the ‘abode of Chir‘ (Pinus roxburghii), is located at an elevation of 3,600 m in the Himalayas on way from Gangotri to Gaumukh, which is the mouth of the Gangotri glacier from where river Ganga originates. Chir is a naturally occurring conifer here at elevations from 800 to 1,600 m. Primarily used for timber, fuel wood and furniture, its leaves are used for livestock bedding and field mulching, while the bark is an industrial source of charcoal, resin and coal tar. Due to its economic and livelihoods benefits, mountains started being denuded of Chir forests in Uttarakhand. However, in recent years, this species is being actively reforested in the state as shown in the above photo in a bid to restore and preserve nature so that atmospheric warming and consequent melting of Gangotri and other glaciers as well as soil erosion can be checked. Reforestation of Chir will also help restore the water cycle on the mountain slopes through carbon sequestration, positive impacts on cloud formation and soil moisture retention after rainfall. Among other measures towards this goal is also the ban on trekking to Gaumukh imposed in 2010, so that tourists cannot approach nearer than 500 m from it.

An Eucalyptus plantation as an afforestation initiative on Nandi Hills in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka

Afforestation is a major instrument for ‘greening’ of barren landscapes under diverse government initiatives. It helps provide hydrological services, other ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, as well as provisioning services for local communities like fuel, fodder, and small timber and non-timber forest products. However, in many places afforestation has occurred in the form of monoculture plantations, particularly of fast-growing varieties like Eucalyptus and Acacia. Eucalyptus is well-known for high water uptake ranging from 50-90 liters a day. In stressful conditions such as drought, its roots are capable of reaching out up to 6-9 m for extracting water. Karnataka is one of the states where groundwater in many districts such as Chikkaballapur, Bengaluru Rural, and Kolar has suffered seriously from Eucalyptus and Acacia plantations that started under the Social Forestry scheme in 1980s. These plantations have caused water scarcity, bringing forth the risk of even desertification. In the face of such threat, in 2017 Karnataka government banned planting of Eucalyptus and Acacia trees in the state. There is need to learn timely lessons from Karnataka and either aim to restore natural forest vegetation or be cautious in selecting the species for afforestation so that these do not end up depleting the very water reserves which were aimed to be augmented through afforestation.

Illegally extracted timber seized by authorities in Karbi-Anglong district, Assam

In a bid to protect forests, at many places these have been declared as ‘reserved’ or ‘protected’, where even activities like hunting, grazing, etc. are either banned or allowed for only dependent communities living on the fringes. While protective forest legislation is the first necessary step, effective implementation of these laws is equally important, otherwise timber smuggling from reserve forests can occur, leading to progressive deforestation, with consequent impact on water resources. Karbi-Anglong district, which once boasted of 75% forest cover and was recognized as the ‘lung’ of Assam, is a glaring example. Timber has been illegally extracted from the reserve forests here for long and processed at illegally operated sawmills in Karbi-Anglong and Nagaon districts, to be finally smuggled out to the neighboring State of Nagaland and elsewhere. In recent times, coordinated action by forest authorities and police is helping catch timber smugglers and recover illegally obtained stocks, as shown in the photo above. Such drives on a regular basis need to be intensified at all sensitive locations to help discourage illegal logging, thereby protecting the valuable forests and hence water resources.

Slashed and dried forest vegetation set on fire for creating agricultural fields under shifting cultivation (jhum) in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

Shifting cultivation, locally called 'jhum', is an important cause of deforestation in the North-Eastern Hill region. Jhum is an ingenious system of organic multiple cropping well suited to the heavy rainfall areas on steep hill tracts where terrace or other forms of agriculture is difficult. However, in recent times, the practice has become unsustainable because under increasing population pressure, the natural regeneration period for the forests has come to be shortened to mere 4-5 years. This is leading to disappearance of forests and several negative environmental consequences including warming, reduced and changing rainfall pattern, reduced soil moisture and ultimately drying up of perennial water sources. A discussion has been initiated in recent years by UNDP on making jhum 'sustainable' through participatory land use planning (PLUP) involving local communities. However, considering that forest burning is the core of this practice, it is questionable how jhum can become sustainable from environment and water perspective. In this context, the only sustainable way forward would be to slowly wean the local communities away from the practice through PLUP, supporting them find more sustainable livelihood alternatives on the hills.

Agroforestry in fallow jhum lands in Mon district, Nagaland

For restoring the nature degraded by jhum (shifting cultivation) in the North-Eastern Hill region and enabling consequent recharging of the perennial springs and streams, afforestation has been found to be a viable solution. Practiced in the form of agroforestry – combining raising of trees with crop cultivation - it can help local communities wean away from jhum. An agroforestry-based project called the Nagaland Environmental Protection and Economic Development (NEPED) funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) was implemented as early as 1994. During the first six years of NEPED, over 7 million trees were planted in 1,808 test plots in jhum fields in Nagaland, with many more plots reforested by farmers themselves stretching over approximately 330 sq. km. Gomari (Gmelina arborea), Alder (Alnus nepalensis), Teak (Tectona grandis) and some local varieties were commonly planted. As evident from the above photo, NEPED has enabled restoration of green cover on previously denuded lands, which in turn has helped restore ‘green water’ and hence recharging of natural springs and streams. Further, intercropping with paddy, ginger, etc. has enabled more sustainable agriculture. A number of different agroforestry models have been proposed for the region, aiming at restoring nature and water as well as promoting socio-economic development. These include fruit tree-based agroforestry, fish-based agroforestry, sericulture-based agroforestry, silvopastoral systems and integrated farming. Given their benefits, these models also have the potential of being adopted in other areas where large-scale deforestation is leading communities to water stress and hence thwarting sustainable development.

French bean grown as a horticultural alternative to shifting cultivation (jhum) in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

Horticulture can be a viable alternative to shifting cultivation (jhum), and has come to be promoted under different government programs in the North Eastern Hill region. In Nagaland, the Horticulture Technology Mission has been actively promoted as a result of which vegetable and fruit cropping is being adopted as an alternative to jhum. Vegetables such as French beanas (depicted in the above photo), cabbage, cauliflower, tomato, knol-khol, chillies and radish are increasingly grown. Fruits commonly grown in the previously jhum plots include citrus, pineapple, passion fruit, banana, mango, litchi, kiwi and cashew. There is also emphasis on floriculture within greenhouses and growing of medicinal and aromatic plants. Though horticulture may require water use through irrigation, and may not involve growth of long-term tree canopy, it provides clear benefits over jhuming because regular burning of forests is not required and some green cover is always maintained which in turn helps propagate the water cycle more efficiently.

Rubber plantation on hills of the Western Ghats in Thrissur district, Kerala

Commercial plantations cause large-scale deforestation, and lead to replacement of the natural forest cover by artificially maintained monoculture trees and plants, and these in turn can cause problems with sufficiency and quality of water resources. India is the third largest natural rubber producing country of the world and Kerala accounts for 68 % of planted area and 78 % of rubber production in the country, one of which is shown in the photo above. Other important States are Tripura, Karnataka and Maharashtra. Rubber plantations, native to Amazon rainforests, are associated with water depletion when grown in other areas. Greater annual catchment water losses through large-scale evapo-transpiration have been reported from rubber-dominated landscapes compared to the traditional vegetation cover. Studies therefore suggest that introduction of rubber plantations can reduce the flow of streams, and lead to drier conditions throughout the catchment. In China, it has been suggested that the high rate of evapo-transpiration makes these plantations act as ‘water pumps’, depleting the area of its water wealth. Other kinds of plantations too have varied kinds of negative impact on the quantity and quality of water. There is thus need to adopt utmost care in granting permission to commercial farms. Considering the large-scale environmental (including water) and socio-economic impacts such plantations may cause, it would be important to introduce environmental impact assessment as a mandatory procedure for establishing commercial plantations.

An abandoned open-cast mine without any reclamation, rehabilitation and restoration in Jharia Coal Fields in Dhanbad district, Jharkhand

Mining is one of the top sectors for which large-scale deforestation and landscape changes have taken place in India, with serious implications for water. The impacts become more pronounced in case of open-cast mining. Coal mining in the country has led to massive ecological destruction, with impact on water cycle resulting from deforestation and landscape change, loss of groundwater due to dewatering, and water pollution. While a strong legal framework has evolved over the years for promoting environmental protection in mining areas, non-compliance is high in connection with mine closure, even on part of the state mining sector. In the ‘mining heartland’ of India, within the States of Jharkhand, West Bengal and Orissa and also other areas, scenes like the one shown in the above photo are commonplace. Old inoperational mines are left behind without proper closure, with reclamation, rehabilitation and restoration obligations for ecosystem regeneration neglected by the mining companies. There is need to improve compliance through regular monitoring as well as environmental sensitization, with the government sector companies taking the lead as role-models. Proper closure of inoperational mines by undertaking reclamation, rehabilitation and restoration activities is essential to restoring nature in the mining areas, and therefore contribute to rejuvenating and augmenting the depleted water resources.

Eco-restoration efforts in an overburden dump of the Old Ghutway Colliery in Bokaro district, Jharkhand

Mining processes generate huge amount of rock waste material called 'mine overburden' (OB) and generally, the amount of OB is large in case of open-cast mining compared to its underground counterpart. Sustainable management of the OB is a big environmental challenge, and in most cases, the OB is just disposed of at the surface, leading to soil erosion and environmental (and water) pollution. There is need for extensive planning for control and management of OB to minimize the environmental impacts of mining. Further, the ecological services of the denuded areas buried under OB dumps need to be re-established by eco-restoration processes, of which afforestation is an important mechanism, as portrayed in the photo above. Since the OB dumps are rocky deposits with little or no soil cover, soil moisture is generally lacking, and therefore eco-restoration in such areas may require special care. Afforestation is being attempted in this abandoned OB dump by watering individual plants on a regular basis. There is need to replicate such efforts on a long term basis so that the degraded mining areas can be replenished.

A hoarding aimed at communicating environmental sustainability in the Margherita area of North-Eastern Coal Fields in Tinsukhia district, Assam

Communication about environmental and water sustainability is an important aspect in the process of protection and restoration of nature for water as is displayed in the photo above. There is need to sensitize the users as well as the stakeholders responsible for exploitation and management of nature for fulfilling narrow human needs. However, the messages should be carefully drafted. The message contained in the hoarding above ‘save trees, use coal’ is contradictory because using coal instead of wood is also equally unsustainable due to the negative impacts of coal mining on environment and water as described before. There is need to convey clear and correct messages in the process of environmental communication, so that the stakeholders can be correctly guided towards appropriate action.

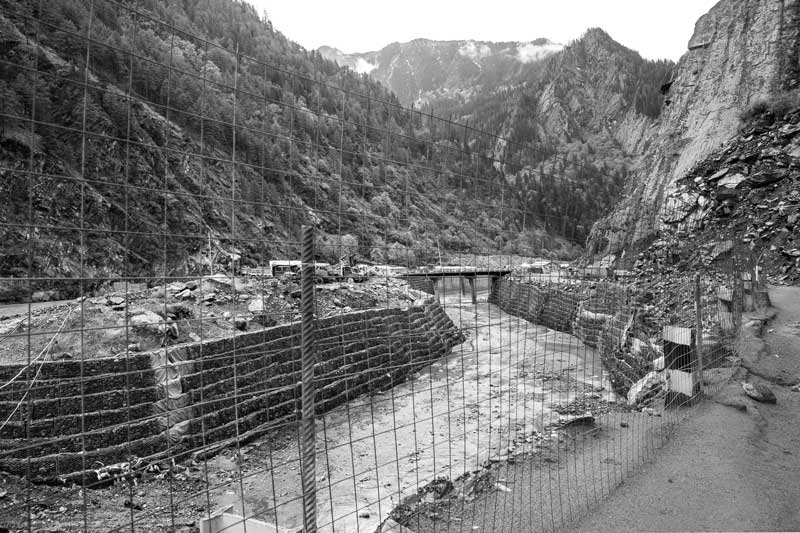

The suspended Loharinag-Pala Hydropower Project on river Bhagirathi in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

Hydropower projects cause large-scale degradation of nature through deforestation and landscape change, which in turn brings about negative hydrological changes. The Loharinag-Pala project on river Bhagirathi, shown in the above photo, was one of several hundred dams and barrages planned or constructed mainly for hydropower in the southern foothills of the Himalayas. Constructed by the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) Ltd staring in 2006, in an effort to shift from thermal to hydropower which is believed to be more environmentally sustainable, the project was stopped in 2009. The closure was motivated by the fast unto death started by Professor G. D. Agrawal - one of India's eminent scientists - in protest against the harnessing of the river Bhagirathi which is the headstream of the Ganga River. According to the environmental impact statement (EIS) prepared by the NTPC the main adverse environmental impacts were to be changes in the river hydrology, a decline in the quality of aquatic ecosystems, loss of agricultural and forest land, and resettlement. Indeed, as a consequence of construction of several hydropower projects in the area which include dams and barrages, local communities have started suffering because of atmospheric warming, reduced river flows, reduced soil moisture, and reduced or erratic rainfall, ultimately resulting in drought. Against this background, there is need to rethink upon hydropower production as a sustainabile option, with emphasis being instead placed on development of alternative energy sources so that environmental damage can be minimized.

Solar power as a sustainable alternative for hydro- and thermal power generation in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Given the darker sides of coal and hydropower as energy sources, which cause large-scale degradation of nature through deforestation and landscape changes ultimately bringing adverse impact on water, a sustainable way forward is the use of alternate renewable sources of energy. India is a country with plenty of sunshine round the year. Development and use of solar power thus holds great potential. India has already expanded its solar-generation capacity several times during the previous decade, with a current solar installed capacity of 20 Gigawatts (GW), with the average current price of solar electricity lower than the average price of its thermal counterpart. In addition to the large-scale grid-connected solar power initiative depicted in the above photo, India is also developing off-grid solar power for local energy needs, and solar products are increasingly helping to meet rural needs through solar lanterns, solar home lighting systems, solar street lighting and solar cooker. Rajasthan is blessed by nature with maximum solar insolation in the country and abundant barren land suitable for installation of solar power plants, one of which is shown in the photo above. Government of Rajasthan has adopted a Solar Energy Policy in 2014 and at present it is the leading State in India with total commissioned solar capacity of 1177 Megawatts (MW).

The Jaisalmer Wind Park generating environment-friendly wind power in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Wind power is yet another sustainable alternative for power generation that can help reduce degradation of nature and therefore water through coal mining and fuelwood use. Wind power generation capacity in India has been increasing in recent years, and presently at 32.96 GW, the country has the fourth largest installed wind power capacity in the world. This is mainly spread across the South, West and North regions. Wind power accounts for nearly 10% of India's total installed power generation capacity with nearly 70% of wind generation occurring during the five months from May to September coinciding with the Southwest monsoon season. The Jaisalmer Wind Park shown in the photo above is India's second largest operational onshore wind farm. Developed by Suzlon Energy, it was initiated in 2001 and has an installed capacity is 1,064 MW, which makes it one of world's largest operational onshore wind farms.

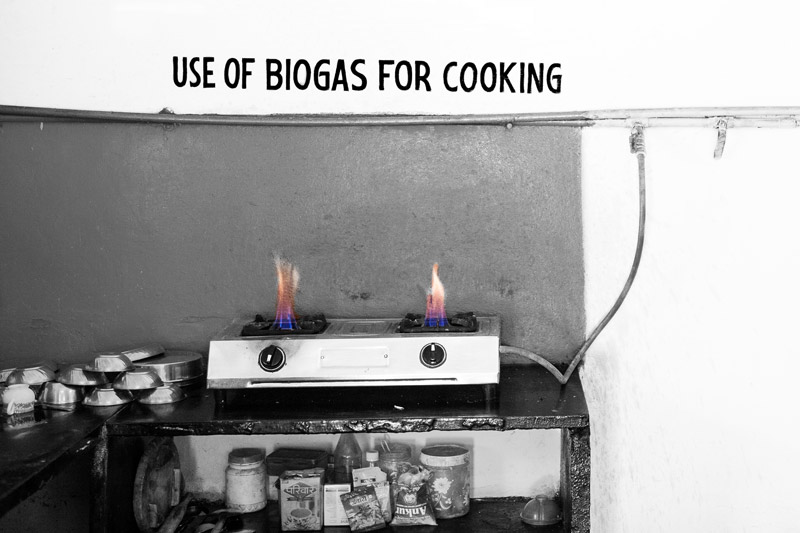

Use of biogas as a sustainable energy source for cooking within a community toilet-cum-bath complex managed by Sulabh International at Shirdi in Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra

Biogas is yet another sustainable energy source that can be retrieved from human waste, animal waste or other kinds of biodegradable waste. Sulabh International is a non-profit voluntary organization well-known for its intervention in developing biogas as a sustainable energy source. Sulabh runs over 8000 public toilet complexes in India, and at some of these complexes, underground biogas digesters using the human waste from the toilets have been installed that produce biogas which can be put to different kinds of consumptive uses including power generation, lighting of lamps, cooking and body-warming equipment. The government also supports use of biogas as an alternate energy source under the National Biogas and Manure Management Programme (NBMMP). Biogas digesters serve dual-purpose: reduce dependence on thermal and hydro-power at local scales, thereby helping reduce the deleterious impact of the former on nature and water, and they also enable water quality protection through sustainable waste treatment. There is need to popularize this option particularly in the rural areas where on-site sanitation facilities enable availability of human waste and rearing of livestock makes animal waste available. In Begaluru city, a recent project for biogas production from biodegradable waste collected from vegetable markets, commercial malls, hotels & restaurants etc. is a welcome step. Such initiatives need to be popularized and replicated.

Cowdung cakes as a sustainable biofuel-based energy source in Varanasi district, Uttar Pradesh

Instead of coal or firewood, use of both of which have negative implications for nature and water through different pathways, use of cowdung as a biofuel is a more sustainable option. Cowdung is thus a source of ‘green energy’ which can be used either for biogas production in digesters or else directly dried into cakes which can be used as fuel for cooking and heating.

Fetching firewood from Bhairon Dev public sanctuary – a forest restored and conserved through community participation - in Bhaonta–Koylala village, district Alwar, Rajasthan

Sustainable forest restoration and conservation cannot be handled by the Forest Department alone. It requires participation of the community that lives in the neighborhood and uses and impacts them in different ways on a day-to-day basis. In Alwar district of Rajasthan, local community in village Bhaonta-Koylala, has reforested about 12 sq. km. of the village area and declared it as a public wildlife sanctuary called "Bhairon Dev Lok Van Abhayaranya", the first of its kind in the country. This is a public initiative taken under the guidance of the NGO Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS), where protection of the local flora has helped in water conservation by checking soil erosion, preserving sub-soil moisture, and slowing down the speed of the runoff during rainy season. Afforestation and restoration of the forest has also improved firewood accessibility for village women. The community is responsible for maintaining a balance between fulfilling of human needs and the needs of nature by formulating its own rules and their strict adherence. According to these rules, green branches and trees cannot be cut but only dry branches can be collected for firewood. For rejuvenation and sustainable management of forests with a view to augment local water resources, there is need to sensitize and motivate masses at large to rise to the cause and share the responsibility.

Soham Baba – a religious/spiritual Guru sensitizing disciples and masses about the importance of afforestation at Kumbh Snan – the great ritual bathing festival – at Haridwar in Uttarakhand

Religion shares a close relationship with nature and water. In Hinduism as also in some other mainstream religions and tribal religions, nature and water are seen as gifts of the Almighty and hence humans seen as responsible for protecting and conserving it. Religious leaders can thus play a significant role in sensitizing masses about the issues concerning degradation of nature and its impact on water, helping motivate followers for positive action. Kumbh has been described as the world's largest religious congregation where millions of devotees come together. As shown in the photo above, Soham Baba - a spiritual leader who is the Mahamandaleshwara of the Hindu Juna Akhara - utilizes the opportunity to raise awareness about global warming and its connections with nature and water, sensitizing devotees about their religious duty to engage in appropriate action. Following Soham Baba's efforts, it further emerges that religious leaders, and also other prominent personalities and celebrities, who often have large followings and enjoy recognition and respect in society, can play a key role as ambassadors in awareness campaigns as well as actions regarding strengthening of the bond between nature and water.

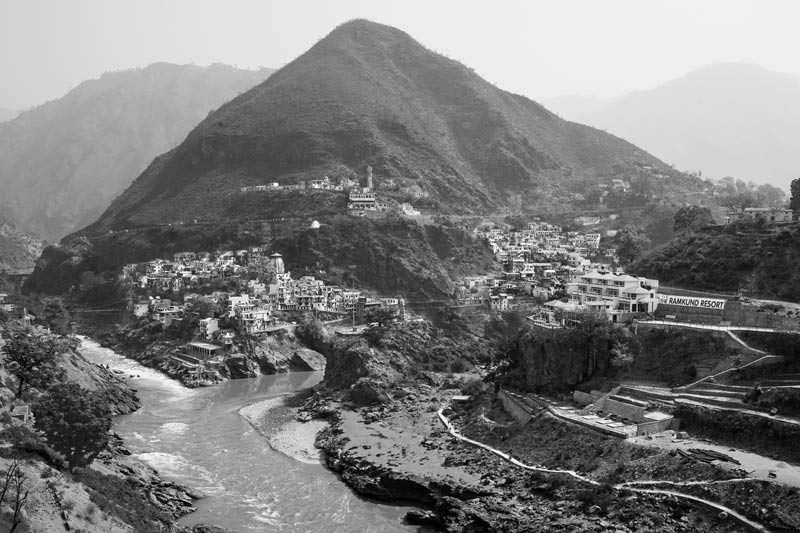

Devprayag – an expanding pilgrimage and tourist center in district Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakhand

Promotion of tourism requires laying down of certain necessary infrastructure which includes at the least accommodation; roads, railways or other transportation facilities; provision of water and food; and waste and wastewater management. All this in turn may involve expansion of tourist centers into previously uninhabited areas and therefore deforestation and degradation of nature in different ways. The Himalayas are an important tourist destination and a number of centers in this mountain range are being gradually developed to attract tourists for different purposes. Devprayag is a small town in the Himalayas where rivers Alaknanda, Bhagirathi and the mythical Saraswati confluence to form the holy Ganga river. Also footprints of Lord Rama are believed to exist here at Ram Kunda. Every year this town is visited by thousands of tourists for pilgrimage, mountaineering and trekking, water adventure and rafting, sightseeing and leisure. To improve access to and around the area, new roads have been constructed, and for accommodating the increasing number of tourists, new lodging and boarding facilities are being constructed by cutting down the forests and changing the natural landscape. However, there exist no proper waste and wastewater treatment facilities yet, which imply their disposal directly into the river course, thereby impacting the river water quality. For protection and restoration of nature in relation to tourism promotion, there is need for more efficient and environmental-friendly planning and better waste and wastewater management, so that nature is minimally disturbed.

This photo story has illustrated some mechanisms and initiatives in place for protection and restoration of nature for water. It has also presented some thoughts on what more is needed to be done so that the degraded nature can be rejuvenated, ultimately ensuring that water continues to be produced, augmented and conserved. One of the significant causes of degradation of nature is the need for energy, through coal, hydropower and firewood. The solution for halting further damage on this ground lies in switching over to alternate, more sustainable sources of energy. Solar, wind, or even tidal energy can be harnessed for producing electricity instead of hydel and coal-based thermal power. Biogas and biofuel (e.g. cowdung cakes) can replace firewood, while biogas can also drive generators for electricity production. Solar power can be also directly used for cooking and heating. Mining, industrialization and urbanization are yet other important causes of degradation of nature, that impact water through multiple pathways, and so does commercial plantations. There is need for developing more stringent legal framework backed by more efficient machinery and procedures for their effective implementation so that accountability of the actors is enhanced, environmental damage minimized and local water resources consequently revitalized. In areas where deforestation is a result of logging, similar solution is required so that timber smuggling can be contained, and where timber extraction is initiated by the government, the norm of reforestation must be strongly followed. In the areas where restoration of forests is hampered by shifting cultivation, alternate modes of sustainable livelihoods have to be adopted so that local communities can be weaned away from this practice without losing their socio-economic viability. The scope of environmental impact assessment needs to be broadened and applied for pre-assessment of economic interventions that can bring any intended or unintended impacts on natural landscapes. This needs to be followed by effective implementation of the environmental impact statement so produced.

Since the various purposes for which deforestation and landscape changes cannot be halted, at least not completely, the approach should be to minimize the short-term and long-term impacts and strengthen efforts to protect and restore nature, and thereby enhance water sustainability. It is also important to recognize that no government or agency can single-handedly handle these responsibilities. There is need to adopt a participatory approach and engage local communities in restoration and management of their natural resources. Finally, since water is everybody’s business and several different actors, including local communities, industries, businesses, government and non-governmental agencies, etc. are involved, there is need for communication and sensitization of all stakeholders. This can be made more effective by engaging prominent personalities and celebrities from different walks of life. Spiritual leaders can play a special role in this effort especially in India where religion and spirituality continue to provide moral and ethical guidance to people. It is utmost important to realize and appreciate that nature and water share a deep bond. Destruction of nature not only disturbs the water cycle directly but also impacts indirectly by fueling climate change. Availability of sufficient and safe water is essential to enable people to enjoy their human right to water and several other connected rights. Short-term socio-economic gains can lead to long-term unsustainability. A number of Sustainable Development Goals, namely 'no poverty' (1), 'zero hunger' (2), 'good health and well-being' (3), 'quality education' (4), 'gender equality' (5), 'clean water and sanitation' (6), and 'climate action' (13) are closely connected to the strengthening of the bond between nature and water through policy and actions for protection and restoration of nature. There is need to consider the urgency of the matter and undertake appropriate action so that sustainable development of society and enjoyment of human rights can be ensured.