Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and Environment

Waterscapes

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

26 January, 2016

India possesses a remarkable diversity of waterscapes. The inland surface water resources comprise rivers, lakes, tanks, ponds and others. Groundwater also comprises an important resource used widely for domestic and productive purposes. Besides, there exists a long coastline which provides access to vast marine water resources.The primary source replenishing the country's diverse waterscapes is precipitation, 3/4th of which is received as monsoon rainfall during June-September. While the average annual rainfall is high at 1160 mm, the spatial distribution varies widely. Mawsynram, Meghalaya in the North-East receives 11690 mm but Jaisalmer, Rajasthan in the West gets only 150 mm. India supports 1/6th of the world population with only 1/25th of the world's water resources. With an ever-increasing population, growing economy and transforming lifestyles, per capita water availability is declining fast. Within 60 years it has dropped from 5200 cu.m. (1951) to 1545 cu.m. (2011). Water availability is further projected to decline to 1340 cu.m. by 2025, and finally to 1191 cu.m. by 2050. According to international norms, an availability of less than 1700 cu.m. makes a country 'water stressed' while that of less than 1000 cu.m. makes a country 'water scarce'. Climate change is expected to further affect precipitation and water availability. Another serious challenge is the deteriorating surface and groundwater quality. The number of polluted rivers in India has more than doubled over the past five years, while groundwater at many places contains impermissible levels of arsenic, fluoride, lead, cadmium, chromium, etc. Given this scenario, the urgent need is to manage and use India's water resources wisely. This photo story presents a virtual tour of the diversity of waterscapes from different corners of India. The title photograph is of river Brahmaputra near Neemati Ghat, Jorhat district, Assam.

Gangotri glacier at Gaumukh in Uttarakhand, the source of river Ganges

The Great Himalayas in North India is home to more than 18000 glaciers which are the source of the three great river systems, namely Ganges, Brahmaputra and Indus. Most of the glaciers lie in the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. Besides being the source of origin of rivers, the glaciers also maintain a regular water supply in them during the dry season. The Gangotri glacier, situated in Uttarakhand state, is the longest glacier in the Indian Himalayas, measuring up to 30.2 kms. From the mouth of this glacier – called Gaumukh – river Ganges originates. River Yamuna, the longest tributary of the Ganges, similarly originates from Champasar glacier at Yamunotri, also located in Uttarakhand. As many as 75% of the Himalayan glaciers have been found to be receding. Gangotri glacier alone has retreated more than 1500 m in the last 70 years, with an annual retreat rate between 13 and 23 m. The current trends of glacial melts suggest that the great Himalayan rivers, presently heavily dependent upon glacial melt water, would flow as seasonal rivers in the near future.

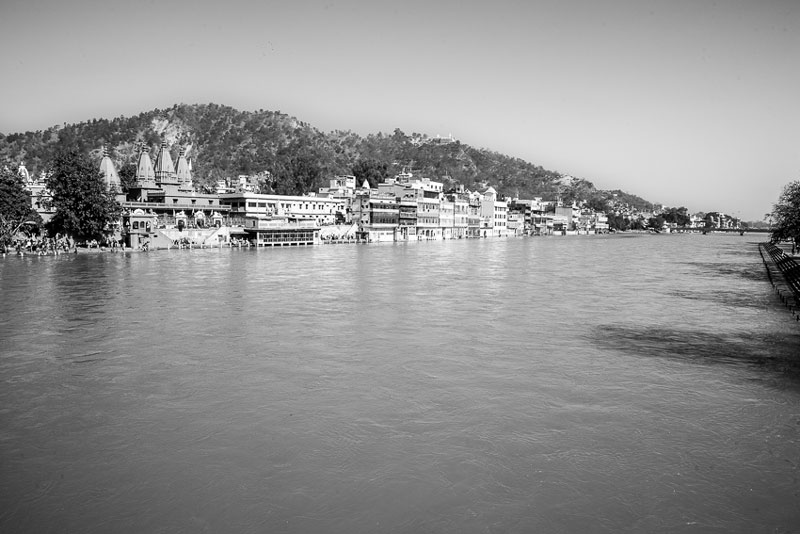

River Ganges at Haridwar, Uttarakhand, touching the plains for the first time

River Ganges and Mahatma Gandhi Setu at Patna, Bihar. Width of the river here stretches from 4-6 kilometers

River Brahmaputra near Neemati Ghat in Jorhat district, Assam

India is a land of many rivers. Its geographical area is intersected by a large number of big and small rivers, classified into 24 major river basins. The average annual surface water resources, constituting river flows as well as the water in lakes, tanks, etc. is 1953 billion cubic meters (bcm), of which 690 bcm is utilizable. Two major categories of Indian rivers are the Himalayan and the Peninsular rivers. The Himalayan rivers are perennial as they primarily originate from glacial meltwater. Of the three major Himalayan river systems, Ganges and Brahmaputra are the largest in India. Together with Indus, they drain almost half the country, carrying more than 40% of the utilizable surface water. In fact, Ganges basin alone covers 26% of the country's geographical area. Ganges is also the longest river in India, flowing through 2525 kilometers to empty into the Bay of Bengal, where together with Brahmaputra, it forms the world's largest delta. The largest average annual flow is that of Brahmaputra at about 629 bcm while that of Ganges is second at about 525 bcm. Ganges is the lifeline for more than 500 million Indians who live along its course. It is also the most sacred river for the Hindus. However, it has been ranked as the fifth most polluted river of the world, the pollution threatening not only humans but also the fauna. Sewage from many cities along the river's course, industrial waste and religious offerings wrapped in non-degradable plastics add large amounts of pollutants to the river as it flows through densely populated areas. Another problem concerning the Himalayan rivers is floods. These rivers see two seasonal peaks in flow – one during the spring snowmelt and the other during monsoons. The monsoon rains particularly makes them swell, causing inundation of villages and towns, and leading to yearly calamity in states like Bihar and Assam.

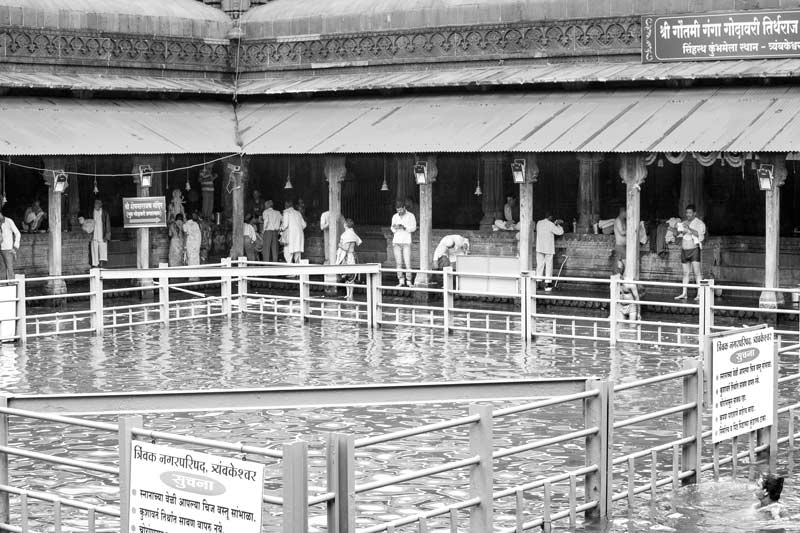

River Godavari at the point of its emergence at Kushavarta Ghat, Trimbakeshwar, Maharashtra

River Godavari flowing further down through Nashik district, Maharashtra

Athirapally Falls on river Chalakudy in Western Ghats, Kerala

Unlike the Himalayan rivers, those in peninsular India are mainly rain-fed. During the dry summer season, the flow diminishes in most large rivers and even disappears completely in smaller tributaries and streams, only to be revived in the monsoons. Peninsular India has several important river systems. Of these, the Godavari is the largest, with an average annual flow of over 110 bcm. It is also the second longest river in the country flowing over 1465 kilometres from its origin in Brahmgiri Hills, Western Ghats in Maharashtra to drain into the Bay of Bengal in the state of Andhra Pradesh. Dubbed as 'Dakshin Ganga' or the South Ganges, more than 60 million population depends upon it. The river also holds great religious significance for the Hindus. Amongst other larger river systems in Peninsular India are the east-flowing Krishna, Mahanadi and Kaveri that empty into the Bay of Bengal, and the west-flowing Narmada which drains into the Arabian Sea.

There are several smaller rivers in the peninsular region, such as the 44 rivers of Kerala that originate in the Western Ghats but are small in terms of length, breadth and water discharge. Chalakudy is one of the longest rivers of Kerala that drains into the Arabian Sea. It is perhaps the richest river in India in terms of fish diversity and is well known for beautiful waterfalls – Athirapally and Vezhachal and its hydroelectric projects. Pollution and overexploitation of the river flow are the major challenges facing the Peninsular rivers. Most of the rivers— including the major ones like Godavari, Kaveri and Krishna, and the smaller ones like Chalakudy - have unacceptably high levels of organic pollution, low level of oxygen availability for aquatic organisms and bacteria, protozoa and viruses that have faecal-origin and cause illnesses. Unfortunately, as much as 90% municipal wastewater flows untreated into the rivers. The frequent drying up of the Godavari river in the drier months has been a matter of great concern, regarding which indiscriminate damming has been seen as a cause.

Vembanad Lake in Alapuzzha district, Kerala - the longest lake in India

Jaisamand in Udaipur district, Rajasthan - one of the biggest man-made lakes in the world

The diverse geographical structure and huge river line forms numerous lakes in India, which number more than 140. There are also hundreds of smaller lakes. Though there is no orderly or scientific census of lakes, the lakes are often classified as natural versus manmade lakes, freshwater versus brackish water lakes, and lakes of southern peninsular India versus those of the Himalayan region. Jaisamand, also known as Dhebar Lake, is India's largest man-made lake and also one of the biggest in the world. It has an area of 87 sq. km when full, and was created by Rana Jai Singh of Udaipur who built a marble dam across the Gomati River in 1711-1730. The dam is 366 m long, 35 m high and 21 m broad at the base. When first built, Jaisamand was the largest artificial lake in the world, till the building of the Aswan dam in Egypt by the British in 1902. The maximum length of the lake is 14 km, and the shore length is 48 km. There are seven islands in it, out of which only three are inhabited. Located in semiarid Rajasthan, this lake never dries up, and is the source of drinking water for the city of Udaipur, besides providing irrigation water around through channels as well as groundwater recharge.

Among other important lakes of India are Wular Lake in Jammu and Kashmir which is the largest freshwater lake. It lies at an altitude of 1,580 m, with a length of 16 km and breadth of 10 km. The lake plays a significant role in the hydrographic system of the Kashmir Valley by acting as huge absorption basin for annual floodwater. Sambhar Lake in Rajasthan is the largest salt water lake while Chilka Lake in Orissa is the largest coastal saltwater lake. The longest lake is Vembanad which is also the largest lake in Kerala, with a length of over 96.5 km and width of approximately 14 kilometres at its widest point. It is fed by ten rivers, and is part of Vembanad-Kol wetland system which is included in the list of wetlands of international importance, as defined by the Ramsar Convention. The lakes of India today face several challenges – the most important being pollution and encroachment. Many lakes have become the dumping ground for city sewage, while many others have been filled up and constructed for urban development. For example, urban and rural districts of Bengaluru were historically endowed with 1545 lakes, but over 45 sq. km of lake beds has been so far encroached. Similarly, Vembanad lake has been heavily reclaimed for paddy cultivation and other purposes, with the water spread area reducing from 290.85 sq. km in 1917 to 227 sq. km in 1971 and 213.28 sq. km in 1990, a total reduction of about 63% of its area.

Sulekere in Devangere district, Karnataka - the second largest irrigation tank in Asia

Tanks are artificial reservoirs of any size which symbolize an ancient Indian tradition of harnessing local rainfall and water from streams and rivers for later use, primarily for agriculture and drinking water, but also for sacred bathing and ritual. Historically, tanks were often constructed across a slope so to collect and store water by taking advantage of local mounds and depressions. Tank use is especially critical in parts of peninsular India where in the absence of perennial rivers and streams, water supply replenishment has been dependent upon harvested and stored rainwater from the monsoon seasons. Though their exact numbers is not known, it is estimated that about half a million tanks exist all over the country but these water bodies indicate widespread decay and decline, mainly due to heavy siltation and inadequate maintenance. However, many tanks are still functional and continue to be maintained by informal community institutions. During the last decade both the Government and some international agencies have been trying to revive, expand and revitalize the tanks.

Sulekere, also called Shanti Sagara, is Asia's second largest irrigation tank. It is a 800 years old tank, created in 1128 by princess Shantava. The tank, which has a shore length of 30 km, irrigates more than 20 sq. km of land and more than 50 villages are benefited by it. The tank also supplies drinking water to the city of Chitradurga. Maximum length of the tank is 8.1 km and the maximum width is 4.6 km., while the surface area is 27 sq. km. The tank was created by construction of an embankment between two hills, the length being around 290 m but width being a stupendous 37 m. The main road connecting Channagiri and Davanagere passes over this embankment. The embankment has two sluices - to the north is "Sidda", to the south is "Basava". Notwithstanding the damaged state of the sluices today and the great force of the water when escaping through them, the embankment has always remained firm and uninjured, a satisfactory proof of the solidity of the structure.

Rain-bearing monsoon clouds at Mawsynram, East Khasi Hill district, Meghalaya. Thick, swirling clouds give this northeastern state its name – 'the abode of clouds'.

Continuous mist hangs over Mawsynram almost throughout the monsoon season, reducing visibility to near zero. It is the wettest place known in the world.

The precipitation received in India is of the order of 4000 bcm. About three-fourth of this is received as rainfall during the southwest summer monsoon season in June-September. During this season, massive convective thunderstorms dominate India's weather. A product of southeast trade winds originating from a high-pressure mass centred over the southern Indian Ocean, the southwest monsoon arrives in two branches: the Bay of Bengal branch and the Arabian Sea branch, which together cover almost the entire Indian territory. During the post-monsoon period October-December, a different monsoon cycle - the northeast (or "retreating") monsoon, brings dry, cool, and dense air masses to large parts of India, but significant precipitation in Tamil Nadu and parts of Kerala. Monsoon is the most important season for the country, since agriculture which employs 600 million people and composes 20% of the national GDP, depends upon rains. While good monsoons correlate with a booming economy, weak or failed monsoons result in droughts and widespread agricultural losses, substantially hindering livelihoods and economic growth.

Meghalaya in the North-East receives rains from the Bay of Bengal arm of the southwest monsoon. The monsoon clouds fly unhindered over the plains of Bangladesh for about 400 km and thereafter hit the Khasi Hills in Meghalaya which rise abruptly to a height of about 1370m above mean sea level. The geography of the hills with many deep valleys channels the low-flying moisture-laden clouds from a wide area to converge here. The winds push the rain clouds through these gorges and up the steep slopes. The rapid ascent of the clouds into the upper atmosphere hastens the cooling and helps vapors to condense, producing high rainfall in the region. Earlier the highest rainfall point was Cherrapunji (or Sohra) but now it has shifted to Mawsynram, about 10 kms away. In 1861, Cherrapunji created a world record with 22,987mm of rainfall in a year. While clouds formation still takes place at Cherrapunji, the rainfall has reduced to being just one third of what it was in the 1970s. Residents report that the place is hotter, drier and shorter of water than even before. Deforestation due to illegal logging and mining has badly damaged the forests around Cherrapunji, which in turn has adversely affected the local ecology. In nearby Mawsynram, with an average annual rainfall of 11,690mm, low cloud formations move through the hills, suddenly enveloping houses and people in soft white blanket of invisibility.

Groundwater irrigation at village Araila, Bhojpur district, Bihar

Annual replenishable groundwater resources of India are estimated as 432 bcm of which 396 bcm is utilizable. Of this, the lion's share goes for irrigation at 325 bcm, while the rest is available for provision of domestic, industrial and other uses. The annual potential natural groundwater recharge from rainfall is over 342 bcm, which is about 8.56% of total annual rainfall. Besides, groundwater recharge augmentation also occurs from canal irrigation which is about 90 bcm. Considering the volume of available groundwater resources, its development has been rampant across the country. About 70% of irrigation and 90% of drinking water comes from groundwater sources. It is contributing more than 85% of the drinking water requirements of rural areas and more than 50% of the urban and industrial water supplies. However, the incessant and mindless withdrawal over the past decades has suddenly triggered off a series of crisis. Dependence on groundwater increases manifold in the absence of rainfall or surface water-based irrigation. Delayed rainfall is also compensated through groundwater irrigation. Excessive drilling of borewells, along with the use of mechanized pumping has led many parts of the country's groundwater aquifers to go dry and have been declared as 'dark zones'. The rate of extraction is alarming and even fossil aquifers have been explored. The worst affected are the states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, parts of Andhra Pradesh and western Madhya Pradesh where water was abundantly available 10-15 years ago. The groundwater table in these areas has fallen below 300 m now, and drought has become a yearly phenomenon.

Arabian Sea at Thottapally village, Alapuzzha district, Kerala

India's coastline stretches over more than 7500 km, which provides access to marine water resources located in the Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean. Besides providing livelihoods through fisheries and seafood production, marine water resources provide the possibility of producing high quality clean drinking water for addressing the increasing water demands. Also, they are an important source for renewable energy production. Total identified potential of tidal energy from these resources is about 9000 MW and that for wave energy along 6000 km of the coast is estimated to be about 40000 MW.