Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and LivelihoodA story based on the theme of World Water Day 2018

Ahar-Pyne: A Nature-Based Solution for Water for Agriculture in Bihar

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

25 September, 2018

Water is a central resource for agriculture, but the sustainability of this resource is becoming increasingly threatened in India. The necessity of securing water sustainability for making agriculture sustainable has been discussed in an earlier photo story dated 15 February 2018, where adoption of nature-based solutions (NBS) was stressed as a way forward. NBS are actions inspired by, supported by or copied from nature, as defined in the UN World Water Development Report 2018. These often simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic co-benefits and also help build resilience. Ahar-Pyne - the traditional irrigation system of Bihar - is one such classic example of NBS that basically harvests the monsoon rainfall collected as surface run-off within a series of embankments from upper to lower catchments that are interconnected through a network of drainage channels. The water reservoir so created by the embankment is called ahar while the drainage channels carrying the water to or away from it are called pynes. The system helps sustainably fulfil agricultural water needs of the local communities, together with major co-benefits of flood control, drought resilience, soil moisture enhancement and groundwater recharge. The system was developed more than 2,300 years ago in the South Bihar plains – the region lying between the southern bank of Ganga river and the Chotanagpur Plateau. Here the landscape is unsuitable for agriculture due to limited rainfall, soil with low water retention capacity, and a steep gradient of one meter for every kilometer. However, the innovation of ahar and pynes has miraculously transformed this region into the ‘rice bowl’ of Bihar. Water conserved in the ahars is diverted through pynes to irrigate fields sown with paddy or other crops during different phases of the agricultural cycle. It is no wonder, as indicated by written history dating back from about 300 BC, such as Kautilya’s Arthasastra and the Greek diplomat Megasthenes’ travel account of India, the Ahar-Pyne irrigation system lay the foundation of Maurya Dynasty’s triumph and expansion. The system gained further importance and expansion during the Sultanate and Mughal periods (1100–1800 AD). The value of Ahar-Pyne system was once again noted in early 19th century by the British surveyor Francis Buchanan who wrote that the ahar-pynes “contain so considerable a (water) supply that they enable the farmer to not only bring the crop of rice to maturity, but to rear a winter crop of wheat and barley.” According to current government records, there exist around 21,000 traditional irrigation systems comprising of Ahar-Pynes/irrigation ponds in Bihar, irrigating about 333,000 ha agricultural land across 17 districts. This photo story makes a presentation of the awe-inspiring Ahar-Pyne system of Bihar which has remained operational through centuries. It takes a closer look at Kaimur district where a total 1,401 Ahar-Pynes/irrigation ponds exist on government records. The story focuses on Patesar Ahar and its successor in the series – Ailae Ahar, both located in Chand Block, Kaimur district. Patesar Ahar, portrayed in the title photo, is located in village Patesar where, according to the Census of 2011, a population of 2,242 resides in 356 households.

A view of Patesar Ahar showing one of its side embankments

Ahar-pynes as the traditional irrigation system exists in as many as 17 districts of Bihar. According to government figures from 2015, in the descending order of the number of systems in existence, these districts are: Gaya (7,264), Jamui (2,522), Banka (2,263), Nawada (2,859), Aurangabad (1,693), Kaimur (1,401), Bhagalpur (522), Jehanabad (501), Rohtas (417), Nalanda (320), Patna (298), Lakhisarai (266), Munger (166), Sheikhpura (151), Bhojpur (124), Arwal (102) and Buxar (69). An ahar consists of a major embankment created across the line of the local drainage with two side embankments running backwards from its two ends. The latter gradually lose their height to match the gradient of the surface. The fourth side is left open for the drainage water to enter. An ahar is different from a regular tank because the bed is never dug out but desilting of the bed needs to be regularly arranged. Ahars are of various sizes. Generally those located towards the top are larger, since they receive more water from the run-off and act as feeder for others located downstream. Patesar Ahar, shown in the above photo, is a large ahar - the topmost in a series that feeds other ahars downstream. According to the farmers of the village, Patesar Ahar is spread over an area of about 175 hectares (ha). The ahar is sourced from natural drainage and irrigates fields located along its sides and downstream.

Sluice gates on the side of the highest embankment in Patesar Ahar

The shape of an ahar is ordinarily U-shaped or rectangular, and height of the embankment is low, being only 1-2 m. The highest side of the embankment in an ahar is provided with an opening, which may be in the form of sluice gates as shown in the photo above. The gates are closed when the ahar is being filled and the intention is to hold the water. These are opened as soon as the ahar gets filled so as to prevent unnecessary flooding of the nearby fields or damage to the embankments. These are also opened when water is to be released through the pyne originating at the gates.

Karath Pyne originating from the sluice gates at Patesar Ahar

Karath Pyne carrying water away from Patesar Ahar

Pyne is the local name for the diversion channels that carry water between ahars or from ahar to the fields. These channels criss-cross the land and form a complex network. These may be of various sizes, with the larger ones helping divert water further downstream to succeeding ahars or into fields. A large pyne could have several branches, with those having 10 branches called dasian pynes, irrigating several hundred hectares of lands across a cluster of villages. The smaller pynes may just carry water from ahar to cultivable plots nearby. Pynes also help in effectively controlling flooding of the fields during monsoon because the streams in the area tend to swell easily with the sudden drainage coming from the rains. This sudden discharge is quickly dispersed through the pyne network and also diverted for storage in the ahars. The remaining water is discharged finally into rivers downstream. Karath, shown in the above photo, is the major pyne originating from Patesar Ahar. A few more originate from the other embankments of this ahar. These smaller pynes as well as Karath carry water to village fields in the vicinity and downstream. Besides, Karath Pyne also transfers water from Patesar to Ailae Ahar located further down in the series. Ailae Ahar is further connected to Srihira Ahar through the Ailae Karath pyne. This last ahar drains into the local Gehuwana river, that in turn drains into Durgawati, and finally to Karamnasa river which is a tributary of the Ganga river.

Water from the Karath Pyne being diverted into a paddy field for irrigation

For irrigating fields adjoining the pynes, water is diverted directly by creating a narrow passage in the side wall of the pyne. The passage is blocked as soon as adequate water has been transferred to the field, as shown in the photo above.

Water level in a smaller pyne from Patesar Ahar being raised through temporary earthen bunding to enable irrigation

In order to use the water carried in the smaller pynes for irrigation, the water level is raised in the concerned section by putting up a temporary earthen bund across the flow. When enough water has been transferred from the pyne to the field, the bund is removed in order to resume its flow for use in fields located further downstream. The photo above shows one such instance of this mechanism.

Using pumpset for lifting water for irrigation from Ailae Ahar

As water level in the ahar and pynes drops, it becomes increasingly difficult to withdraw water directly from these structures and distribute to agricultural fields further away. In this situation, the pumpset is often used as shown in the photo above. According to farmers, other traditional mechanisms were used for this purpose in the past.

Paddy being transplanted in a field along the Karath Pyne using water from Patesar Ahar

Irrigation of both monsoon (kharif) and winter (rabi) crops is facilitated by water from the Ahar-Pyne system. Paddy is the major kharif crop irrigated using ahar water. Since paddy cultivation requires complete flooding of the field, depending upon the quantum of natural rainfall received in the season, the fields may come to be irrigated from an ahar at the early stage of paddy transplantation, as shown in the photo above. Subsequently, the fields come to be watered a number of times during the cropping cycle using water from the ahar.

Paddy crop growing in a field irrigated by water from Patesar Ahar

As long as sufficient stocks last in the ahars, water from there is diverted for irrigation, as has been done in the photo above. Thereafter, the water remaining in the pynes is used up. The latter is more common during the rabi season, as the ahars start drying up or are drained out by then. According to farmers from Patesar village, irrigation with water from ahar-pyne system is more profitable in comparison to other sources such as canal or groundwater, as the agricultural yield is 1.5-2 times greater. This happens because irrigation water in the ahar-pyne system is rich in nutrients brought along from the surfaces over which it flows.

The substantially dry bed of Patesar Ahar

After the final round of irrigation of paddy crop in October, ahars may be drained out or their water stock may diminish. At this time, a substantial part of the ahar bed gets dried up, as shown in the photo above. The dry ahar bed is then prepared for sowing of rabi crops. However, in some deeper pockets of the bed, water may remain which is used later for irrigation of these crops.

Rabi crops growing in the dry bed of Patesar Ahar

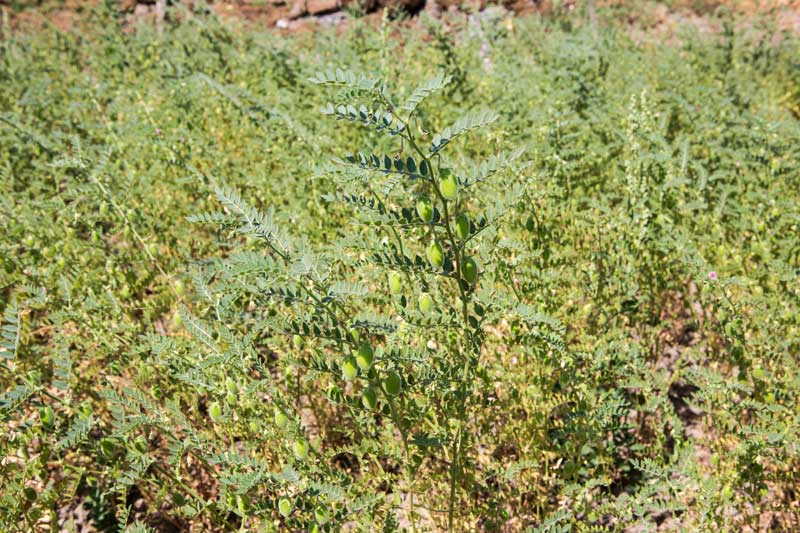

Mustard, Bengal gram (chana), peas, grass pea (khesari) and lentils (masoor) are traditionally grown as rabi crops in the ahar bed. These are grown primarily with the aid of existing moisture in the soil and without application of any fertilizer, since the soil of the ahar regains fertility through addition of fresh sediment every year. In recent times, wheat is also being increasingly grown as a rabi crop in the ahar bed. The productivity of rabi crops improves with 1-2 irrigation, for which water remaining behind in the deeper pockets of the ahar or in a nearby pyne is used up.

Rabi crop growing in the dry bed of Patesar Ahar on another side

Mustard crop growing in the bed of Patesar Ahar near the sluice gates

Pea crop growing in Patesar Ahar bed

Bengal gram (chana) growing in Patesar Ahar bed

Lentil crop growing in Patesar Ahar bed

Mustard crop growing in Patesar Ahar bed

Wheat crop growing in Patesar Ahar bed

Embankment of dry Karath Pyne being used for growing pigeon pea (arhar) crop

Apart from the ahar beds which yield good rabi crops due to moisture retained in the soil, the embankments along the pynes are also used for raising crops. Here too, much moisture is retained even after the water has dried up in the pyne during the rabi season and hence pigeon pea (arhar) is commonly grown, as shown in the above photo.

Mature Pigeon pea (arhar) crop on the embankment of Karath Pyne

This photo story has made a presentation of the Ahar-Pyne system as a nature-based solution (NBS) for water for agriculture in Bihar. This is one of the oldest irrigation systems of the world, and represents the state of the art in sustainable water resources management, which continues to hold central relevance and remains in use in contemporary times. It is a completely decentralized irrigation system, traditionally practiced at the level of village communities through centuries. It is rooted in the principle of rainwater harvesting where the run-off is impounded in the fields through a series of embankments and then distributed through a network of channels. The water so conserved in the system is used for irrigating the monsoon (kharif) and winter (rabi) crops during different phases of the cropping cycle. Besides, given the higher moisture content in the ahar soil, the bed of these structures is also used as fields for growing of rabi crops. This NBS offers several co-benefits – first, it brings direct economic benefits by increasing the crop yield and enabling agriculture through provision of timely irrigation; second, it augments both surface and groundwater, thereby enhancing water availability for livelihoods and basic human needs; third, it serves as an effective flood control mechanism by quickly conveying the floodwaters away through the pyne network; and fourth, it also offers resilience to droughts through enhanced availability of water and persistence of higher soil moisture even during low rainfall years. Flood protection and drought resilience together enable social and economic stability in the face of climatic uncertainties. History shows that during the Bihar famine in 1873-74 caused by delayed rain, the erstwhile Gaya district (presently including Gaya, Nawada, Aurangabad and Jehanabad districts), required no relief. However, the same region (particularly Jehanabad) was in grip of severe drought in 1950-52 and 1957-59, and even worse, the famine of 1966 struck this entire area as intensely as the rest of Bihar. The reason was degradation of the Ahar-Pyne system particularly in the aftermath of development of canal irrigation system. Serious efforts at rejuvenation of the system during the last decade has improved the situation. During our field visit in the year 2013 when many districts of Bihar were declared as ‘drought-affected’, the ahar-pyne areas in affected Kaimur district were found to remain comparatively immune and could produce substantial paddy crop.

As a NBS, the Ahar-Pyne system offers many benefits when contrasted with the canal system of irrigation. It is a decentralized system where small embankments within village areas are able to store enough water required for irrigation at the local scale. It thus does not bring disadvantages like large-scale land submergence and displacement. Moreover, the land in the reservoir area is submerged for just about 4-5 months, while it remains available for raising crop and animal grazing during the remaining part of the year. Moreover, and very importantly, it is not just an exploitative technology for consuming the surface water for irrigation. It represents a cyclical process of water utilization and management where the runoff along steep slopes which would have otherwise flowed away wastefully is harvested, then circulated through the chain of ahars and pynes, and through fields, with the unutilized water released back into rivers at the end. The implications of this NBS for sustainable water resources management and also sustainable agriculture are more than obvious. The technology is simple, based on local resources and requires simple skills. Hence, maintenance is simple and cost-effective, can be managed at community scale, while the economic returns are high. It also delivers greater drinking water security due to regular groundwater recharge and promotes over-all sustainable development in the region. The benefits to women and girls in terms of access to water and food is thus high, and it promotes enjoyment of the human rights to water, food, livelihoods, health, etc. for everyone. The benefits for climate resilience have already been elucidated before. Recognizing the multiple benefits offered by the Ahar-Pyne system, in the recent years there has been much concern with reviving the system in Bihar. The government of Bihar has assumed the responsiibility of their renovation and maintenance through a special 'Minor Water Resources Department' under which the "Mukhya Mantri Ahar-Pyne Yojna" has been launched. In addition, ahar-pyne renovation works are being undertaken under MGNREGA and even several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have taken lead independently. There is need to learn lessons on water sustainability for sustainable agriculture from this age-old NBS of ahar-pyne and adapt it more widely across water-parched areas in the country that otherwise have sufficiently good rainfall, so that they too can follow the path of sustainability.