Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and Livelihood

Fish Farming in Waters of Abandoned Mine: An Innovative Livelihoods Approach in Jharkhand

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

22 May, 2023

Water is an essential resource for sustaining life and development. Not only is it needed for drinking and other personal uses, but several livelihoods are moderately to heavily dependent on water. In rural landscapes, this strong dependence is more than obvious in sectors like agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture. On the one hand, water stress can cause impoverished livelihoods, in turn bringing poverty and food insecurity, while on the other hand, development and prosperity may be bolstered through smart use of available water resources. This photo story presents the case of a rural community where water stress hindered agriculture as the main source of livelihood, but innovative utilization of an hitherto unused surface water body for fish farming has opened new livelihood opportunities. This has been achieved through an innovative cage fish farming project in the district of Dumka located in the tribal heartland in Jharkhand state. Dumka is a picturesque district, famous as the land of temples, also as a health hill resort. However, this predominantly rural district is socio-economically backward and has been long affected by left wing extremism. Consequently, it is assessed to have poor performance with respect to vital development indicators like health, nutrition, education, and agriculture. The district is home to a large tribal population – more than 43% (Census of India, 2011), which includes a number of ‘particularly vulnerable tribal groups’ (PVTG), most notably the Paharias. A major part of the district is rocky, and the water table is considerably low. Coverage of canal network for irrigation is limited, as is the availability of ponds and lift irrigation schemes. As a result, agriculture is substantially rain-dependent, and recurrent droughts in recent decades have increasingly impoverished the agricultural livelihoods base. Consequently, Dumka continues to be assessed as one of the 112 most backward districts of India, and presently with the aim of promoting rapid development, it has been included in the ambitious national initiative called ‘Aspirational Districts Programme’. The innovative cage fish farming project has been started in Nandna, an erstwhile stone mining village, located in Patjor Gram Panchayat (village-level local government) in Ranishwar Block. With a current population of 787, the primary livelihood in the village is agriculture. However, a significantly deep water table, coupled with recurrent drought and limited financial capital, has increasingly challenged agro-based livelihoods. With a view to promoting alternative livelihoods in this impoverished village, the cage fish farming project has been initiated under the able leadership of the Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla, with support from the District Fisheries Department. Funded under a new initiative of the State Government called ‘Cage Culture Expansion and Strengthening Scheme’, it has been set up in a large, abandoned stone quarry pit. This photo story illustrates how the cage aquaculture project in the abandoned mine waters is bringing about a transformation in Nandna village and its surroundings. The title photo presents a birds-eye view of the cage fish farm in the abandoned mining pit at Nandna village, Dumka district, Jharkhand.

Gurdayal Mandal, President of the self-help group that owns and manages the cage fish farm

The cage fish farm in village Nandna is owned and managed by a self-help group (SHG) called ‘Kaveri Cage Culture Samiti’. Led by Gurdayal Mandal as the President, the SHG comprises 24 members who belong to the socio-economically weaker sections, particularly the Other Backward Classes (OBC), Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). As explained by Gurdayal, given the persistent difficulties in pursuing agro-based livelihoods, the new cage fish farming scheme in abandoned mining pits from the government came as a boon to the local community. Under the guidance of the Dumka district administration, 24 of them decided to come together and pool their financial resources and efforts to jointly start the new venture as a SHG. Following on-site training from the Fisheries department, the group finally started the pilot cage culture project in June 2022.

Some of the members of the SHG Kaveri Cage Culture Samiti

22 members of the SHG that manages the cage fish farm belong to Nandna village, while two of them are from the neighboring villages Paharpur and Naugaon. In order to operate in a more organized manner, the group has applied for registration under the Fisheries Cooperative Act. They will also receive further training at the state level later this year.

The abandoned mining pit with the floating cage fish farm

The abandoned mining pit in Nandna remained neglected as a wasteland for ten years. However, it continued to harvest and store the local runoff from a large catchment, resulting in a surface water body, as seen in the photo above. The surface area measures roughly 2 hectares while the depth is more than 15 meters. Since the base of the pit is rocky, there is almost no seepage, and consequently a substantial water stock is retained round the year. The mining pit is close to the village settlement and is easily approachable by road. These characteristics made the Nandna site extremely suitable for initiating the cage fish farming project. Consequently, with the Kaveri Cage Culture Samiti taking up the responsibility, the project came into being.

The cage fish farming infrastructure

The cage fish farming infrastructure at Nandna primarily comprises the cage unit and the cage house, as seen in the photo above. The cage unit further encompasses 12 cage batteries. A battery, in turn, comprises twin cages, with each cage structure basically made of a GI pipe-fitted rigid frame measuring 8m x 6m. The batteries in the cage unit are arranged in a linear sequence of six each, with the two resultant series of batteries placed adjacent to each other. The overall layout is such that better exchange of water is enabled, thereby facilitating relatively high dissolved oxygen for optimal fish growth.

A closer view of the cage unit, showing the GI-pipe frames fitted above floating empty PVC barrels

The GI-pipe fitted frames of the cages are fixed on top of a series of empty PVC barrels which work as floats. This allows the entire structure to remain above water, as seen in the photo above. To provide stability to the infrastructure and prevent its drifting, anchors are tied at corners and dropped to the floor.

The catwalk, cage rails and the nets

The cage unit is provided with walkways around each cage structure in such a way that the constituent cages are accessible from all the four sides. This is called the ‘catwalk’ and comprises galvanized iron sheets fixed over the PVC floats. Each cage further has double rails above the bottom frame made of GI pipes to which the netting of the cage is tied. A view of the catwalk, rails and nets is seen in the photo above.

The nylon net cage body inside which the fish are raised

The GI pipe rails provide the structure to which submerged knotless nylon netting is attached as the cage body. It is inside these net cages that the fish are raised. The dimensions of each net cage are 8m in length, 6m in width and 5m in depth. In the above photo, the net has been pulled out of the water to show the details.

The top cover in a cage unit for protection against predators, with floating fish feed seen underneath

The fish in the net cages are exposed to the risk of being attacked by predators, particularly different kinds of birds. They may even attempt to eat up the feed provided for the fish. A top cover nylon netting, is thus tied securely to the GI rails above every net cage, as shown in the above photo. This cover protects the fish and their feed from bird attacks.

The floating cage house as a part of the infrastructure

The cage fish farming infrastructure includes a floating cage house which is used as a storeroom for storing feed and other essentials. It is also used as a resting place and shed during night-vigil.

The raft for traversing the mine waters to access the cage fish farming unit

Ease of mobility between the banks of the pit or the cage house and the cage unit is essential for managing the fish farm efficiently. The SHG has been thus facilitated with a PVC raft. Also, to ensure the safety of the SHG members who work amidst the deep waters of the mine pit, soft neopolene foam and airex filling life jackets have been provided to the group. Both the raft and life jackets are seen in use in the above photo.

Members of the SHG busy with their daily chores at the cage unit

The members of the SHG which owns the cage fish farm at Nandna work hard for cage as well as stock maintenance with the aim of maximizing the fish production. Among important routine activities are providing supplementary feed to the fish, monitoring the water quality, cleaning of the net cages, routine checking of the structure, health check-up of the stocked fish, and monitoring of their growth rate. Some SHG members are seen in the above photo preparing to feed the fish.

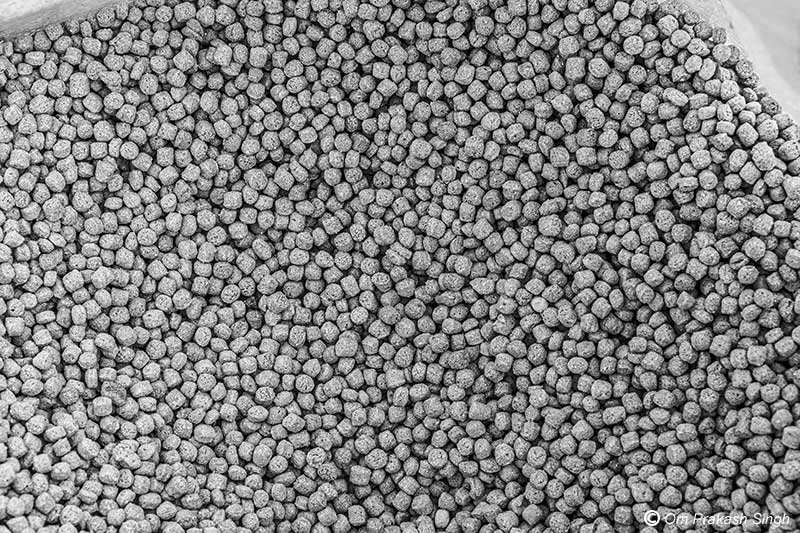

Floating fish feed as supplementary diet for the growing fish crop in the cage batteries

Cage fish farming is purely raised on supplementary feeding and its application in the right quantity is important to achieve desirable results. Fish feed is thus the most important input in this project and only good quality floating feed is to be used for this purpose. The feed provided to the fish is shown in the above photo.

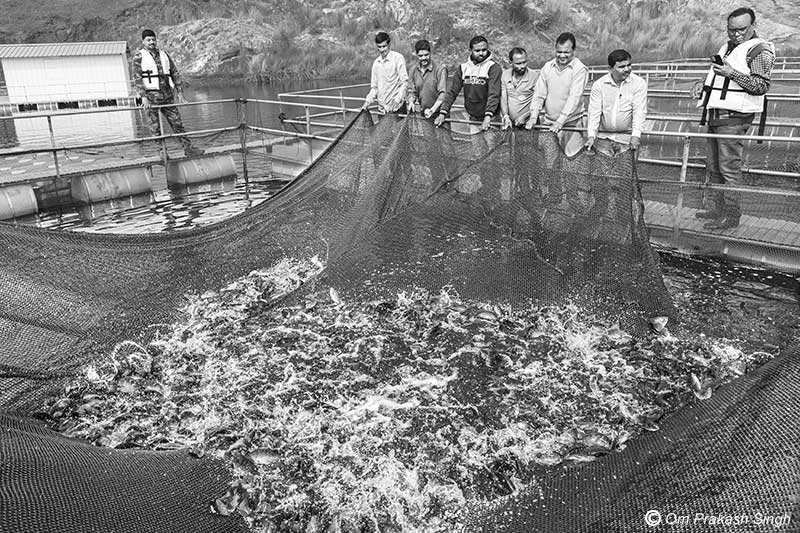

SHG members proudly displaying their fish stock

The most important asset at the cage fish farm is the fish reared in the net cages. Two varieties of fish are being raised in Nandna, namely, Pangasius (Pangasiandon hypopthalmus) and Monosex Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Tilapia is grown in only two batteries while all the remaining contain Pangasius.

A glimpse of the Monosex Tilapia fish crop raised in one of the net cages

A closer view of the Monosex Tilapia crop, at an age of six months

A view of Pangasius fish raised in the cage unit, at an age of six months

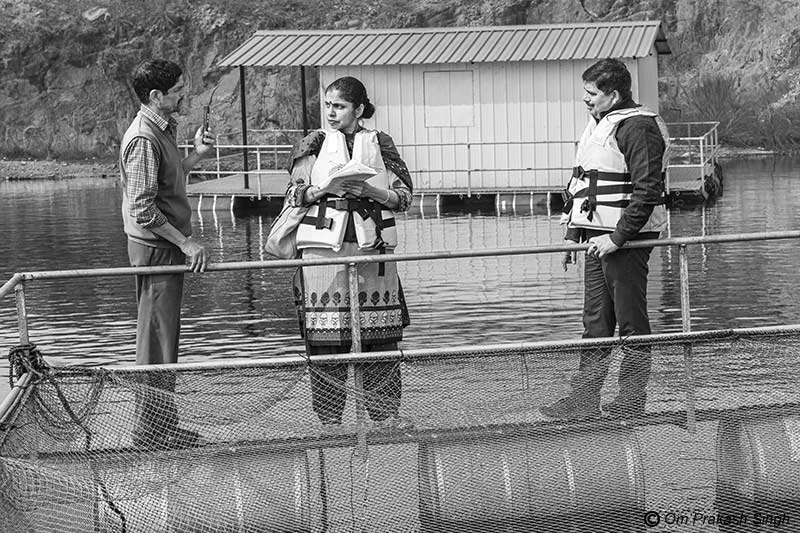

Nandita Singh from Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden in conversation with a SHG member and the District Fisheries Officer

As informed by the SHG member Ganesh Chandra Maharana and the District Fisheries Officer Amarendra Kumar, seen in the photo above, the total cost of the cage infrastructure (including the cage batteries and the cage house) was Rupees 5.28 million (approx. 63,764 USD). 90% of this amount was in the form of a grant from the government, while the remaining 10% was the beneficiaries’ own contribution. In order to keep it affordable for the poor locals as beneficiaries, two SHG members have been made joint owners of one battery. The total cost of the fish feed and other input has been Rupees 2.4 million (approx. 28,970 USD), which included a 50% grant and 50% contribution from the beneficiaries. In addition, the fingerlings for both the fish varieties were provided by the Fisheries department as a grant.

Secretary of the SHG Krishna Dom, briefing about the group’s efforts and plans

As explained by the secretary of the SHG Kaveri Cage Culture Samiti - Krishna Dom, though the cages are individually owned, all the members work unitedly as a team. All farm-related activities are carried out solely by them in batches. After unrelenting efforts for about nine months, the group was rewarded with its first fish crop in March 2023. They successfully produced a total yield of 50 tons, comprising 40 tons of Pangasius and 10 tons of Monosex Tilapia. The fish was sold in the local markets in Dumka district as well as in the adjacent districts of West Bengal and Bihar states. The sale of the entire production yielded a gross income of Rupees 5 million (approx. 60,355 USD), out of which the net profit for the group has emerged as Rupees 2.6 million (approx. 31,406 USD), which is a very good income. Approximately another 10 tons of fish remained in the cages for sale in early May. Fresh seed will be stocked again at the end of May, which will be reared for the next harvest in November 2023. While the fish farming is fully handled by the SHG itself, marketing of the fish has involved the participation of other local people, with overall support from the district administration.

This photo story has illustrated how utilization of hitherto unused water resources through innovative approaches can prove to be a game changer for impoverished rural livelihoods. The efforts of the state government in Jharkhand which brought a new development scheme towards this end is appreciable. Even more appreciable are the efforts of the Dumka district administration that successfully motivated the local community in and around Nandna village to pilot this new project. Especially important has been the administrative leadership shown by the Deputy Commissioner Ravi Shankar Shukla and the officials of the District Fisheries Department. The greatest appreciation remains for the members of the SHG Kaveri Cage Culture Samiti who undertook the risk of trying a novel livelihoods approach that involved not only a completely new income generation activity, but also a new social organizational form that requires joint working of different socio-economic groups (castes and tribes) in the local community. Thus, apart from boosting alternative livelihoods, the project also has contributed to building of social capital.

The cage fish farming project in the abandoned mine waters of Nandna village has emerged as a successful pilot that should motivate other rural communities to consider replicating this model for prosperity. Presently, two more such projects are under planning in the district itself. The case study re-establishes that water lies at the core of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework. Not only does the better known Goal 6 (clean water and sanitation) deal with water, but the Nandna case makes it obvious that water is also the vital basis for Goals 1 (no poverty) and 2 (zero hunger), through Goal 14 (life below water). Several other SDGs are also directly or indirectly related to water.

The Nandna project offers useful lessons for socio-economic development in rural areas via the strategy of fish farming. It testifies that cage culture in an existing water body is an effective approach for enhancing rural livelihoods, offering a number of benefits. First, cage culture is practiced in areas that are already under water, such as reservoirs, lakes, oceans and other kinds of large and deep unused water bodies. Hence it presents an approach of maximizing the productive use of available water resources, which could be especially valuable in water scarce areas. In the Nandna case, cage culture helped ‘add’ a huge volume of water for productive purposes from the abandoned mining pit. This water body was until recently neglected as a ‘waste’ and not counted in the available water resources of the district. From this follows the second benefit that cage culture can offer the potential of minimizing the competition for basic resources (water or land) in impoverished local communities while augmenting productive livelihoods. Third, since it is based on naturally existing surface water, it can protect the valuable local groundwater resources from being overused for conventional land-based fish farming because there the shallow dugout aquaculture ponds often need to keep up the necessary water levels through groundwater extraction. This would be especially important where aquaculture has been widely adopted as a livelihood alternative in water stressed areas.

The Nandna case also demonstrates that approaches for addressing livelihoods related challenges need to be grounded in the local context. The new scheme from the Jharkhand government which emphasizes cage culture in abandoned mine waters is a good example because Jharkhand is a mining state with hundreds of old, abandoned mining pits that are filled with valuable water resources. This unused water has the potential to be used for fulfilling different kinds of local needs. One of the earlier photo stories dated 22 March 2023 elaborated how this water could be an invaluable asset for addressing drinking water challenges in local communities. This photo story exemplifies the potential use of these waters for livelihood development. Taking the two cases together, it can be said that the nature of use to which the waters of abandoned mines can be put is varied, being basically case-dependent. However, the human right to water should always be given a higher priority. In the earlier photo story, in Kulkuli Dangal village (also located in Dumka district), drinking water access was the primary challenge but in Nandna, livelihood challenges were more pronounced. From this it emerges that there is a need for the State to consider the water contained in the old, abandoned mining pits of Jharkhand as a valuable resource for the people and their development, and formulate a holistic policy promoting its sustainable use and management. Also, other states having such mine-based water resources need to learn from Jharkhand experiences and develop sustainable policies and actions.