Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and Livelihood

Inland Saline Water Shrimp Farming in Agricultural Fields of Haryana

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

10 March, 2018

The introduction of irrigated agriculture in the arid and semi-arid regions of India has resulted in the development of the twin problem of soil salinization and waterlogging, affecting approximately 9 million hectares (mha) of land. About 40% of this area lies in the three ‘original’ Green Revolution States of Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh alone, where 41-84% of the groundwater is also saline. Mitigation of the problem is possible through measures like subsurface drainage, but its applicability in the field faces the constraint of affordability, particularly in case of small and marginal farmers who predominate in the region. Considering this problem, conversion of affected agricultural fields into saline aquaculture farms has been promoted as a practical solution. Of the various aquaculture options possible, the Central Institute of Fisheries Education (CIFE) has developed a technology for culture of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) using inland saline groundwater. The technology was successfully tested in salinity affected areas in Haryana by the Rohtak Centre of CIFE at Lahli in 2012-2013. Subsequently, it has come to be promoted in the salinity affected villages in Haryana and Punjab, intending to replace ‘Green Revolution’ by ‘Blue Revolution’. With support from the Fisheries Department of Haryana Government, which provides 50% subsidy to shrimp farmers for developing infrastructure and inputs, over 128 hectares of salinity-affected areas in Rohtak, Hissar, Bhiwani, Jind, Sonepat and Jhajjar districts has been already brought under white shrimp farming. The suitability of this practice in the salinity-affected agricultural areas is defended on the following grounds: first and most directly, lowering of the groundwater table by withdrawing saline groundwater for aquaculture, thus helping reduce waterlogging, improving soil and reducing secondary salinization; second, high profit for farmers within similar time frames as in agriculture, since the shrimp produce can also be reaped in 100-120 days; and third, more reliable income due to healthier aquaculture crop resulting from the use of groundwater which is free from pathogens. This photo story presents an analysis of inland saline water shrimp farming promoted in the agricultural fields of Haryana from the perspective of water sustainability. The title photo depicts a saline water shrimp farm located in Lahli village, Rohtak district, Haryana.

CIFE Rohtak Centre located in Rohtak district, Haryana

Central Institute of Fisheries Education (CIFE) is the premier National Fisheries University of India, responsible for the development of the fisheries sector through its three-pronged mandate of research, teaching and extension. The CIFE Rohtak Centre shown in the above photo is located in Lahli village and undertakes research in developing suitable aquaculture technologies for degraded salt affected inland areas using saline groundwater. It also conducts on-farm demonstrations and training programs for fish farmers, entrepreneurs, non-governmental organizations and state fisheries personnel. The credit of optimizing saline water shrimp farming in Haryana, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh goes to this Centre that pioneered testing of the technology in its saline water on-site farms and provided training to local farmers and entrepreneurs in the art and science of this practice. About 70 farmers from salinity and waterlogging-affected areas of not only Haryana but also Punjab and Rajasthan have received training from here and continue to be supported by it for establishing and running their saline water shrimp farms.

Shrimp farmer Sanjit Malik and his farm ponds in village Lahli, Rohtak district, Haryana

Sanjit Malik, a resident of Rohtak town, is one of the local entrepreneurs who received training at the CIFE Rohtak Centre. Supported by a 50% subsidy from the Fisheries Department, he established a shrimp farm in Lahli village in 2015, constructing 11 ponds spread over an area of 4 ha. He has taken the land on lease from a local farmer who found agriculture to be unproductive due to rising salinity in the soil and groundwater. According to Sanjit, the ponds are filled with saline groundwater and the salinity is maintained in the range of 5-10 parts per thousand (ppt) at which very high productivity can be achieved, although white shrimp is known to grow well within a wide salinity range of 5-35 ppt.

Sanjit explaining about the water quality in his farm ponds

According to Sanjit, water quality parameters like alkalinity, hardness, pH, salinity, calcium, magnesium and potassium in the ponds are monitored on a weekly basis. Compared to natural sea water, the saline groundwater used in the ponds is deficient in potassium and magnesium, which play an important role in growth of the shrimp, therefore influencing the productivity. In order to restore the balance of magnesium, commercial grade magnesium chloride is used, while for enhancing potassium level, fertilizer grade Muriate of potash is added several times during the life cycle.

A paddle wheel aerator as indispensable equipment for shrimp farming

For improving production efficiency in shrimp farming, mechanical aeration is a necessity since shrimps require dissolved oxygen for their growth and metabolism. This makes the aerator an indispensable part of shrimp farm equipment. Aerators create strong water movement and turbulence, breaking up the air-water interface. This causes oxygenation, mixing, and destratification of the pond water column, which in turn enhances dissolved-oxygen concentrations and lowers the accumulation of nitrogenous compounds.

A paddle wheel aerator working to circulate water for increasing oxygen availability in a shrimp farming pond

A tubewell in the shrimp farm – an essential part of the infrastructure

Groundwater for the shrimp ponds is withdrawn through tubewells. According to Sanjit, the depth of the water table in the area is more than 6 m, and up to a depth of 15-20 m, the groundwater remains ‘sweet’, with no or very low salinity (less than 3-4 ppt). But beyond this depth, the salinity increases to more than 5 ppt. He has observed that after starting his farm, within a short period of two months, the salinity of one of his tubewells changed from zero to 3-4 ppt. Sanjit sees this as a risk for availability of sweet drinking water in the area over a longer period of time.

Pipes carrying groundwater from the tubewell into the shrimp farming ponds

Groundwater being filled in a shrimp farming pond

A generator used for running all electrical appliances on the shrimp farm

Since there is no electricity supply available in the fields, the tubewells, aerators and other electrical appliances on the farm are run using a diesel generator.

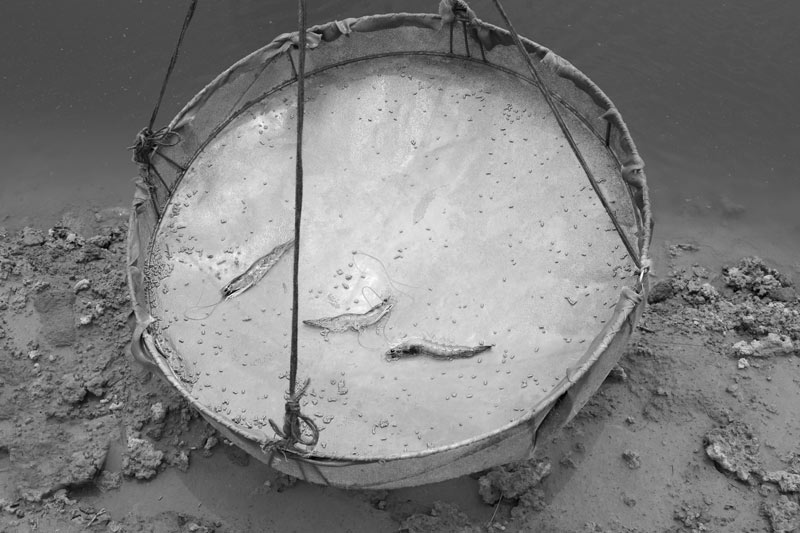

Sampling of shrimps being carried out using a lift net

Sampling of shrimp stocks is carried out at regular intervals in Sanjit’s farm for monitoring growth, health and for adjustment of the quantity of feed to be given at different stages of the growth cycle. Lift net is one of the instruments used for estimating the quantity of feed to be provided to the shrimps.

Young white shrimps brought out in a lift net

Young white shrimps at an early stage of about 30 days

The life cycle of the white shrimp is about 100-120 days. It can gain weight at the rate of up to 3 g per week, with a potential of growing up to 35 g body weight and 230 mm length over this period. During his first harvest, Sanjit sold shrimps having an average body weight of 20 g, which fetched him a good market price. During the first year of the shrimp farming, Sanjit achieved a total production of more than 13 tons/ha over a period of about 120 days. Excluding all recurring, non-recurring and capital costs for production, this helped him earn a net profit of about Rs. 10,00,000 (approx. 15,383 USD) per hectare.

White shrimps at the stage of about 70 days

Plastic lined shrimp ponds in village Lahli

Saline water shrimp farming can have high environmental cost. According to Sanjit, holding of the saline water in an unlined shrimp farming pond can destroy the soil of the pond and affect quality of the groundwater in the neighboring fields. He reported that the groundwater withdrawn for crop irrigation by the farmer adjacent to his shrimp farm has noticed increase of water salinity and decrease of agricultural produce. Besides, loads of unutilized feed, fertilizers and other chemicals used in the farming process remain in the pond wastewater which can leach down into the underground aquifers. Use of PVC plastic pond lining, as shown in the above photo, is a useful solution to address these problems.

PVC plastic lining in a shrimp farming pond

The PVC plastic lining, as seen in the photo above, provides multiple benefits to the shrimp farmer. It can reduce erosion, water seepage, waste accumulation in the soil and the leaching of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, acidic compounds, iron and other potentially stressful compounds into the pond that can affect shrimp productivity in the long term. The lining also allows easy removal of wastes from the feeding areas, reducing the time and costs to clean the ponds between cycles. Additionally, from the perspective of protection of water quality, the PVC plastic lining is extremely useful since it can effectively prevent leaching of various contaminants present in the pond water (including salinity) into the soil and eventually to the underground aquifers. However, PVC plastic lining is expensive and has limited life span. The cost can be up to Rs. 875,000 per hectare, lasting for a period of only 5-7 years. Besides, other disadvantages observed include difficulty in maintaining plankton bloom within the first month of culture, and the problem of tearing and floating of the liner if water and gas accumulate underneath.

It is evident from this photo story that the technology developed by CIFE, Rohtak Centre for inland saline water white shrimp farming can undoubtedly bring prosperity to the farmers of Haryana, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh whose livelihoods have been jeopardized by increasing salinity and waterlogging in their agricultural fields. The Pacific white shrimp has got very high demand both in national and international markets and fetches very high price. Since the life-cycle duration is only 100-120 days, the farmers can easily take two crops per year between March and November, reaping huge profits. However, as the story also reveals, though replacement of ‘Green Revolution’ by ‘Blue Revolution’ can be a harbinger of prosperity in salinity-affected agricultural areas, it does not represent a 'sustainable' and 'eco-friendly' mode of livelihood. In its present form, the practice of saline water shrimp farming raises several questions about water sustainability and therefore sustainable development in the region. First and foremost, the large volumes of saline groundwater (with a salinity above 5 ppt) which is held in the ponds for 8-9 months in a year brings forth the risk of manifold increase in salinity of the soil and underlying groundwater aquifers. Besides, the water in the pond also contains dissolved fertilizers, unused shrimp feed, probiotics, and other additives, which can easily leach down into the soil and the groundwater, further compromising the water quality. In addition, if the wastewater from the shrimp ponds is discharged untreated into canals, streams and rivers, even surface water bodies face the risk of contamination. At present, there exist no specific guidelines with the shrimp farmers about treatment and management of the wastewater derived from the used ponds, which amplifies the risk of water contamination in the area. These realities unfold deeper societal and human rights concerns. Since the deep aquifer is already saline, local communities depend upon shallow groundwater for drinking and other uses. Salinization and chemical contamination of the shallow aquifer as well as the surface water sources due to unprotected aquaculture practices will leave the local communities with no ‘safe’ water resources in the near future. This would impair the enjoyment of the human right to water and health by the women, men and children, due to lack of access to ‘safe’ and ‘sweet’ water. Further, even the possibility of carrying on agriculture in the area will be thwarted due to expansion of soil and water salinity pockets. Together this would pose serious challenges to sustainable development in the area.

Given these implications, there is urgent need to look for more sustainable options. If saline water shrimp farming is to be promoted, then clear guidelines regarding water and soil safety measures must be developed and implemented. For example, use of PVC plastic lining should be adopted together with proper arrangement for on-site treatment and safe discharge of the pond wastewater. The farmers need to be trained about these aspects and the farms need to be regularly monitored for the water and environmental safety standards. Further, if restoring the livelihoods of the farmers in the salinity-affected and waterlogged areas is the primary concern, the government and other development agencies should instead focus on reclamation of the affected lands through implementation of measures like subsurface drainage on larger scales. Further, since rainwater is the purest form of water, reclamation efforts can be strengthened by combining with rainwater harvesting, which can help leaching the salt from the soil as well as dilute salinity in the groundwater. The overall goal should be to promote more sustainable eco-friendly modes of livelihood for the affected farmers so that present food, water and other resource needs of society can be met without compromising the ability of future generations to do so.