Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Drinking Water

Women and Drinking Water Challenges

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

17 October, 2016

In India, women are widely responsible for managing drinking water at home in rural and urban settings alike. However, this responsibility is fraught with challenges. According to 2011 Census, in more than 116 million households in the country, drinking water needs to be procured from outside the premises. These instances imply much hardship for women since they are commonly responsible for procuring water at home, in most cases transporting it manually. Greater the distance to the source, longer is the way over which water needs to be hauled, which may even force women to carry heavier loads in one trip. The intensity of hardship may also vary according to factors such as season, topography, and even age. In the summer season, not only do the trips need to be undertaken in the heat of the day, but even the demand at home may rise and the distance for travel may increase as nearby water sources start drying up. Similarly, carrying water up along hills and mountains is definitely more arduous than doing the same in plains. Where water is to be collected from points that have a time-bound supply, such as public standpoints or water tankers, possible physical struggle poses further challenge. The supply timings may be irregular, forcing women to wait for long hours. Sometimes, the supply hours may be odd such as late in the night, or supply may be provided only once in several days. In the latter situation, apart from uncertain waiting times, women may be faced with the additional challenge of collecting several days’ ration in bulk and transporting these back home. At public standpoints or water tankers, queue and rush for water collection is another common challenge. Apart from the challenges faced in accessing adequate quantity of water, the quality of water obtained is another problem. Groundwater in many parts of the country contains high levels of salinity, iron, fluoride, arsenic, nitrate and other contaminants. At some places, drinking water needs to be procured from unprotected sources such as ponds and streams, which may pose challenge of microbial contamination. Many areas are flood-prone where attempts at procuring safe water for themselves & their families during floods exposes women to a different set of problems. These several challenges in turn thwart enjoyment of the human right to water by affected women and their dependents. This story explores the variety of challenges facing rural as well as urban women in different parts of the country. The title photo depicts rural women carrying headloads of drinking water from a distant ‘sweet’ water pond in salinity-affected Kutch district, Gujarat.

Carrying multiple drinking water containers from a distant tapstand in a village in district Ahmednagar, Maharashtra

Sometimes the drinking water source is so distant that women prefer to carry multiple containers in one trip. This is tiring as well as risky from health perspective as transport of heavy loads of water on the head, shoulders or waist can cause neck and back pain and spinal injury.

Bringing drinking water from a distant well in the scorching heat of the day in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

In the western part of Rajasthan, traditional sources of drinking water are commonly small shallow wells which are generally located outside the village where the natural slopes direct the rainwater to infiltrate into subsurface soil layers. Though drinking water sources have been provided in many villages by the government, these either supply saline underground water or inadequately filtered water from the Indira Gandhi canal. At many places, fluoride concentration in the supplied groundwater is high, making women abandon the government installed sources on health grounds. As a result, women have to travel a few kilometers from the homestead everyday, making multiple trips to procure clean and 'sweet' drinking water from the traditional wells, irrespective of the scorching heat of the day in summers or the biting cold on winter mornings.

A 82 year old woman carrying approximately 45 liters of drinking water on her back up a hilly track in Mokokchung district, Nagaland

In the north-eastern hilly state of Nagaland, villages are generally located on hill-tops where naturally recharged springs provide drinking water for a limited period in the year. In the remaining months, there is need to access alternate water sources down the hill, and much of this burden falls on women as the domestic water managers. Irrespective of age, women are seen to carry water in bamboo pipes kept inside bamboo baskets, each woman carrying loads up to 45-50 liters. Even elderly women may need to procure water in the same way for themselves and/or their families, if need be so. The risk of physical injury due to the heavy water loads is high and the extent of time invested gets higher as the dry season progresses, with women needing to search for sources further and further down the hill. With increasing climate change impact on the Naga hills, the dry season sets in earlier, thereby progressively enhancing women's hardships.

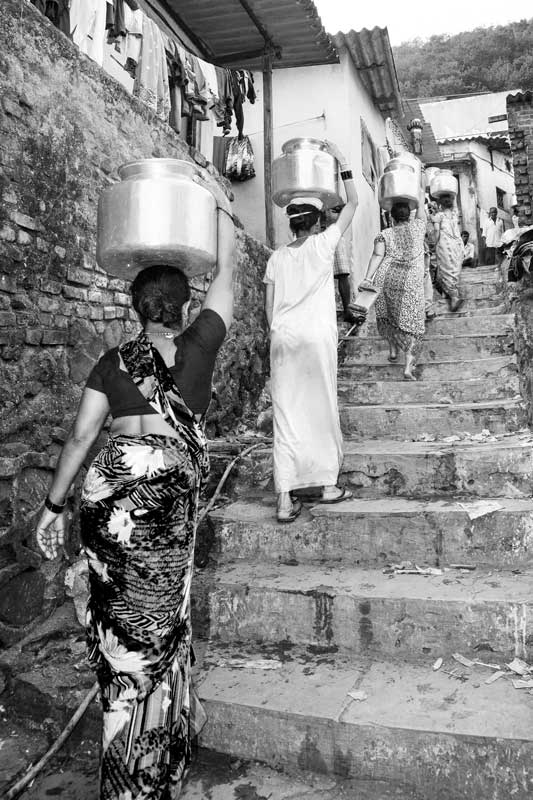

Women carrying headloads of drinking water procured from a group connection in a hilly locality in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Accidents are quite common in this and many other informal colonies in Mumbai, where women face high risk of injury while carrying water home from public sources or group connections. Many of these settlements are situated on hilly terrains and at some places the only water supply hours are in the dark of the night. Generally takers are many but the supply is for short duration, leading to brisk actions causing spilling of water around and making the area slippery. This enhances the risk of tripping, falling and subsequent injuries for women, especially for those who have to carry water up the hills.

Women struggling for procuring a container of drinking water from a tanker in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Many unsettled colonies in Delhi are supplied with drinking water through tankers. However, the tanker is a source of limited quantity of water which may often make women struggle for water amidst great rush. Sometimes, they may have to physically jostle with their contenders and at other times enter into arguments and conflicts for gaining access to the water tanker. Yet, if unfortunate, they may have to finally return home empty handed despite the time and energy spent.

Waiting endlessly for the water tanker in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Water supply at public standpoints or from water tankers may often be irregular, making women wait for long hours, forcing them to lose valuable productive time. This in turn may adversely affect their incomes and also thwart effective execution of their other domestic responsibilities.

Waiting in a queue to fetch drinking water at a public standpoint early at dawn in Bengaluru, Karnataka

In unsettled urban colonies, water supply timings are generally irregular and the duration is short, while the rush is often large. Consequently, women may have to wait in long queues at public water sources alongwith their containers, costing them much time. Sometimes, the water supply hours are odd – too late in the night or very early at dawn. Such odd hours and irregular supply timings disturb sleep, throws daily domestic routines out of gear and affects their socio-economic well-being.

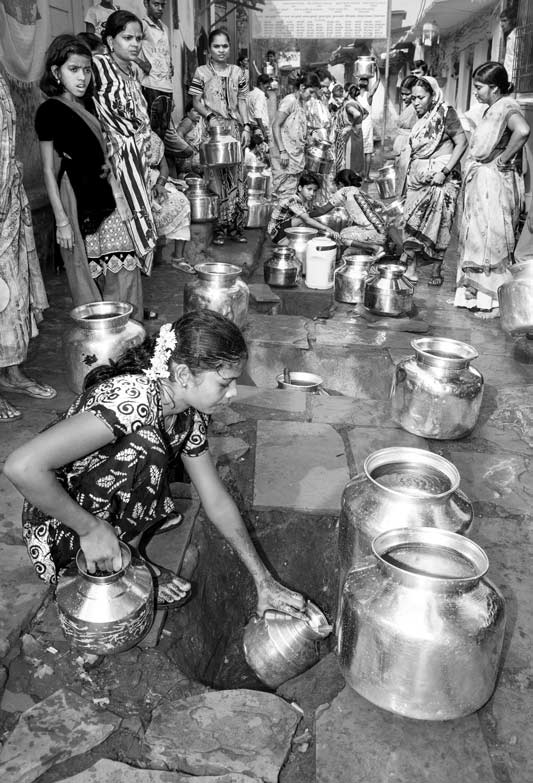

Working hard to procure a share in the scanty water supply at a group connection in an informal colony in Mumbai, Maharashtra

In many informal colonies in Mumbai, women can procure drinking water from group connections. However, the water supply at these group connections is for a very short period and that too at a very low pressure. Moreover, water may not necessarily be supplied everyday and every household in the group may not get a turn every time. Thus, women are faced with challenges of uncertainty, longer time in filling containers and the risk of remaining without water despite the turn.

Employing cycle to transport extra load of drinking water from a group connection in Mumbai, Maharashtra

At group connections in Mumbai, women try to procure the maximum possible supply whenever they get their turn, which may require transport of water in bulk. In such cases, the use of bicycle can be a respite, but there is always risk of losing balance on an undulating path with such a heavy load on it, causing serious injury.

Women preparing to transfer home their weekly ration of drinking water collected from a tanker in a village in South-West district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

In many villages in this part of Delhi, salinity in groundwater is a problem, making the local handpumps and tubewells unfit for drinking. Consequently women have to depend upon drinking water supply from tankers which are provided by the local authorities generally once a week. There, apart from coping with the routine challenges of rush, queue and distance, women are confronted with the additional challenge of transporting home the bulk supplies collected.

Fetching drinking water from an unprotected pond which is used by humans and animals alike in district Kutch, Gujarat

In salinity affected areas in Gujarat such as Kutch district, many regular drinking water sources such as wells and tubewells no longer produce potable water. As a result, women have to search for 'sweet' water sources, pond being a good alternative. However, the drinking water quality of ponds is questionable especially from microbial perspective since water is collected directly by physically entering the water which may bring dirt and germs from the body and feet. Moreover, these are open sources which are shared not only by humans but also by animals.

Procuring drinking water from a roadside pool formed out of water leakage from a pipeline in a village in Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra

Sometimes women discover unique drinking water alternatives in the absence of regular sources. Here they are procuring drinking water from a pool resulting from water leaking out of main pipeline carrying water to a nearby city. The quality of water in this pool is however questionable on a number of grounds. First, the pipeline carries untreated raw water. Second, this source is also used for drinking directly by animals. Third, water from this pool is collected by physically entering into it thereby further polluting the water. Consumption of polluted water by women themselves and their dependents exposes them to health risks.

Women fetching drinking water from a distant tubewell in Jharia coal mining area, Dhanbad district, Jharkhand

In many mining areas of the country, procuring drinking water is a significant challenge for women. This challenge is often quantitative as well as qualitative. Mining, both open cast and underground, often requires regular dewatering which not only leads to wastage of water but ultimately empties out the groundwater reserves, on which local populations thrive. In Jharia coalfields in Jharkhand, the situation is worsened by increased temperatures resulting from continuous fire in the underground coal reserves, together with large-scale deforestation for mining, in turn also leading to reduced precipitation. In the rural communities here as well as urban centres like Dhanbad, the water table is so much depleted that handpump and tubewells have started running dry, especially in the summer season. The water quality is negatively impacted due to discharge of acid mine drainage into local surface water sources, also polluting the groundwater. This forces women to travel long distances in search of adequate and safe drinking water, causing much hardship.

Trying to procure a bucket of drinking water amidst floods in West Champaran district, Bihar

During floods, access to safe drinking water becomes a serious challenge for women. First and foremost, flooding hampers movements, restricting women's access to water sources. Second, the hitherto 'safe' water sources start becoming unsafe since the water quality becomes degraded due to their submergence under flood waters. Thirdly, physical risks such as being drowned or drifting away in the currents of the flood water or being bitten by water snakes or other unseen water organisms becomes high.

The challenges confronting women in managing drinking water for their homes are obviously multifarious. Carrying heavy loads of water manually is not only an arduous task but poses substantial health risks to women. The hardship increases where they have to make multiple trips in a day, or carry water on uneven or hilly terrains, or if older women are forced to transport headloads of water. Seasonal extremes may further intensify the hardship. Uncertainty, irregularity & inadequacy of supply may further cause loss of valuable productive time due to long waiting hours and disturb work routines at home, thereby forcing women to compromise with their incomes and socio-economic wellbeing. Further, despite all these hardships, if the water quality is compromised, diarrhea, fluorosis, arsenicosis, and many other illnesses may affect the health of women and their families. All these circumstances may restrict not only the women but also their dependents from enjoying their various human rights, most notably the rights to water, health, education and development. There is thus an urgent need for the ‘duty-bearers’ entrusted with the responsibility of securing women’s access to water to understand the multiple facets and contexts of these challenges and address these adequately so that women and their dependents across rural and urban milieus in the country can enjoy uninterrupted access to adequate and safe drinking water under all circumstances.