Raising Water Consciousness through

World’s Biggest Photo Exhibition and

Largest collection of Photo Stories on Water

Photo Stories | Water and Environment A story based on the theme of World Water Day 2021

Valuing Water: Contributions of MWS to the World Water Day Theme 2021

Nandita Singh and Om Prakash Singh

22 March, 2021

Water is an invaluable resource essential for nature, life and development. However, as a finite resource it is becoming increasingly scarce in terms of quantity as well as quality, not only in India but across the globe. This is a result of our failure to recognize and acknowledge the multiple values that water holds for us and consequently to manage it judiciously so that these values remain upheld. Considering this reality and its urgency, the United Nations (UN) has focused on "Valuing Water" as the theme for World Water Day 2021. But what does 'valuing water' entail? In general, 'value' refers to the worth, importance or utility of something. In this light, the theme of 'valuing water' should seek answers to the following questions: What are the central values attributed to water by society? How are these values reflected in practice? What mechanisms are adopted by society for upkeep of these values? Alternately, if these values are challenged, what mechanisms can be adopted to re-instate them? Following these questions, it can be said that 'valuing water' entails two distinct connotations. First is the ideational connotation where the emphasis is on the 'what' are the different values water holds in our lives and for the planet? Here again, two types of values can be distinguished – 'intrinsic' and 'instrumental'. The intrinsic value refers to that which water has in itself, for what it is, or as an end. The instrumental value refers to its value as a means to a desired or valued end. These ends could be basic human survival (such as for drinking and sanitation), economic activities (such as agriculture, fisheries or business), cultural pursuits (such as religious, spiritual, leisure, recreation), and environmental goals (such as ecosystem restoration or biodiversity protection). In its second connotation, the emphasis is on the action component - how to reflect the values in day-to-day life and to continually produce (and reproduce) the different water values? An example could be worshipping water or learning about the values as a part of the educational curriculum. It is obvious that an instrumental value of water can be effectively practiced or realized only when the intrinsic value is upheld. For Millennium Water Story (MWS), 'valuing water' has been a consistent cross-cutting theme across the various photo stories published so far. The first four themes under which the photo stories on MWS are classified broadly correspond to the major instrumental values ascribed to water. These four themes of MWS are: drinking water, water and livelihood, water and environment, and water and culture. The fifth category of 'water leaders' elaborates comprehensive efforts made at individual level towards the cause of promoting water values in different ways. This photo story aims to examine the different photo stories published on MWS in a quest to seek answers to the questions on 'valuing water' posed above. The story is primarily organized under four themes that explore the water values and associated processes in relation to: drinking and domestic use, economy and livelihood, cultural pursuits, and environmental goals. The title photo shows the veneration of river Ganga through evening 'aarti' at her banks in Haridwar, Uttarakhand.

Athirapally Falls on river Chalakudy in the Western Ghats in Thrissur district, Kerala

The photo story titled “Waterscapes”, published in January 2016, presents an overview of the intrinsic value that the water resources of India hold for the country. It presents a virtual tour of the diversity of waterscapes from different corners of India. The inland surface water resources comprise rivers, lakes, tanks, ponds, and others. Groundwater comprises an important resource too, besides there being a long coastline which provides access to vast marine resources. Besides, the Great Himalayas in the North is home to more than 18000 glaciers which are the source of the three great river systems, namely Ganges, Brahmaputra and Indus. The story also describes that the water resources of the country face several challenges, which is an expression of degradation of their intrinsic value, caused by multiple factors that result in problems related to water quantity as well as quality.

Domesticated cows quenching their thirst at a pond in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

An overview of the multifarious instrumental values of water in India is presented in the photo story titled "Water for Nature, Life and Development", published in February 2016. Water is essential for drinking and domestic uses, and for food production. Water is also an important driving force behind the development of society and culture. The banks of water bodies have served as cradles of human civilization. Waterways serve as channels of transportation. Hydropower and industries, drivers of contemporary socio-economic development too, depend upon water. The environmental value of water lies in supporting various aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and regulation of the water cycle.

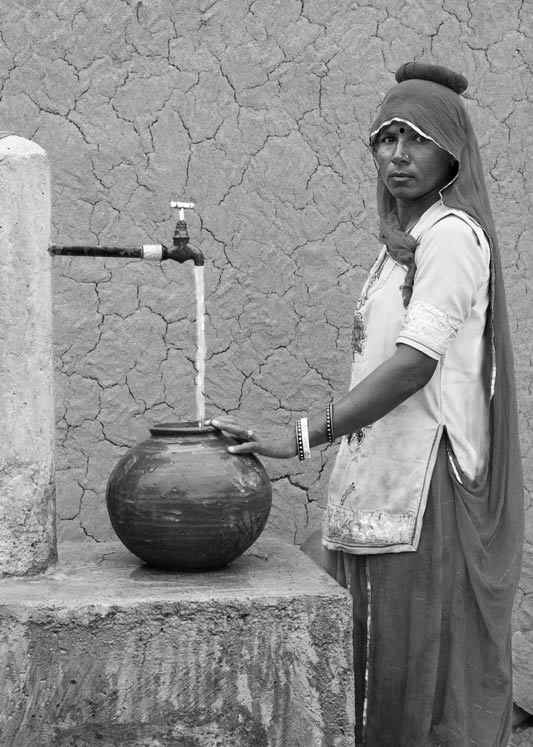

Sufficient water for drinking and personal uses available from a public tapstand in a village in Jaipur district, Rajasthan

The theme of valuing water for drinking and domestic use is illustrated through photo stories on MWS under the category of 'drinking water'. Here a number of sub-themes can be identified. The first one concerns valuing water as a human right, where the photo story titled "Leaving No One Behind: Ensuring Realization of the Human Right to Water in India", published in April 2019, outlines the norms and criteria within the human right to water (HRW) framework that must be followed in order to ensure that no one is left behind in realizing this most basic and essential value of water in India. Several photo stories in the series published between May and September 2019 outline the status of realization of the HRW in different parts of the country, the picture which is quite dismal. The factors impeding the enjoyment of the value connected to HRW in India are outlined in three photo stories published between November 2019 and January 2020. These separately examine the impediments to enjoyment of the 'availability', 'quality', and 'accessibility' norms concerning the right.

A well-protected drinking water pond along with its water treatment plant that supplies safe drinking water in an arsenic-affected village in North 24 parganas district, West Bengal

An integral part of the HRW sub-theme are two case studies. One of them, published in October 2019 under the tile "Industry and Violation of the Human Right to Water in Bichhadi, Rajasthan", illustrates that if the intrinsic value of water is degraded through industrial pollution, upkeep of the instrumental value of water for drinking gets challenged and local communities are unable to enjoy their HRW. The other one, titled "Safe Drinking Water for All in Arsenic-Affected Areas: The Sulabh Innovation", published in March 2019, shows the reverse – if the intrinsic value of water is restored by rejuvenating and sustainably managing traditional water sources through community participation, the instrumental value of water for drinking can be re-instated by sustainably mitigating even serious water quality challenges and help ensure people's right to safe drinking water.

Struggle for collecting drinking water from a tanker in South-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

The second sub-theme in this section represents an analysis of drinking water challenges in India. This sub-theme is important because it sheds light on the circumstances under which upholding the instrumental value of water for drinking and domestic use is thwarted. An overview of the quality challenges confronting drinking water are discussed in a story titled "Drinking Water Quality Challenges", published in November 2016. These challenges confront the country's rivers, lakes and other surface water bodies and also the groundwater aquifers which supply water for drinking purposes. Moving to the urban scenario, a story titled "Urban Drinking Water Challenges", published in January 2017, presents an overview of the challenges thwarting this basic instrumental value of water in Indian cities and towns. A later photo story titled "Integrated Solution for Urban Drinking Water Challenges", published in February 2017, presents recommendations which reflect policies and practices that can help reinstate and enhance the water value for drinking and domestic use. Examples include protection, augmentation and development of existing urban water resources; minimizing water wastage; and promotion of rainwater harvesting; besides recycling and reuse of wastewater. All these measures are reflective of core water valuing principles.

Young girls chatting on the mobile phone while happily collecting drinking water from a shallow well (kuin) situated within the village catchment (paitan) in Binjharwali village, Bikaner district, Rajasthan

An analysis of the challenges and the underlying factors in rural India is presented in a photo story titled "Rural Drinking Water Challenges", published in June 2017. Another story titled "Integrated Solution for Rural Drinking Water Challenges", published in July 2017, provides recommendations to address the challenges, which can, in turn, help re-instate this important instrumental value of water in Indian villages. Examples include water conservation; prevention of water wastage; rejuvenation of traditional nature-based drinking water sources; ecological restoration; rainwater harvesting; effective information, education and communication (IEC); and community participation. A case study from Rajasthan, titled "Best Practices in Rural Drinking Water Management: A Case from Thar Desert", published in July 2017, is further an eye-opener in this direction, where in a village receiving as little as 251 mm of mean annual rainfall, valuing of water through indigenous knowledge and traditional technology has assured people's access to water round the year, even through drought years.

A 'kund' - a large underground tank that stores rainwater harvested from its catchment - in use in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

The third sub-theme under valuing water for drinking and domestic use concerns the relevance of traditional science and technology underlying drinking water supply and nature-based solutions as a way forward. A photo story titled "Traditional Water Supply Science and Technology of India", published in December 2016, presents a virtual tour across a selection of traditional water supply science and technology from different corners of the country. These largely promote a balance with nature, through technologies that are need-based, non-exploitative and sustainable, even helping communities 'climate-proof' themselves. A closely related story is titled "Nature-based Solutions for Drinking Water: Sustainability in Simplicity", published in June 2018. The solutions for drinking water in practice in India presented here include an emphasis on rainwater harvesting for recharging surface water reserves as well as underground aquifers. A nature-based solution describing the benefit is presented in a story titled "Quenching the Thirst in the Driest Place of India: A Nature-Based Solution", published in July 2018. This is from an arid village in Thar Desert of Rajasthan where the mean annual rainfall is barely 100 mm with intermittent drought years, where an ingenious traditional science and technology based on rainwater harvesting enables people to enjoy access to water even in the driest seasons. .

Rainwater harvesting for irrigation through bunding in a paddy field in district Sivasagar, Assam

The theme of valuing water for economic purposes is illustrated through photo stories under the category 'water and livelihood'. Water is a resource of great economic value. Its economic value lies in enabling diverse livelihood and economic practices like agriculture, fisheries and industries. Agriculture is the largest and most important economic sector in India, where water has been ascribed a central value. Within this sub-theme, a number of photo stories have been published. How the value of water for agriculture has been traditionally upheld is described in the story titled "The Science of Traditional Irrigation in India", published in December 2016. The secret is rooted in the fact that traditional irrigation systems place a high value on water, which is reflected in their simplicity and intricate adjustments to the local climatic, hydrological and geographical contexts. This imparts sustainability to agriculture as well as to water, enabling food and water security in local communities through even climatic extremes.

Irrigation of groundnut crop using sprinklers in Bikaner district, Rajasthan

The contemporary scenario regarding valuing water for irrigation is presented through a series of photo stories published between December 2017 and February 2018. The first story, titled "The Role of Water in the Success of Green Revolution in India" illustrates the recent decades. However, as the second story titled "Green Revolution in India and its Impact on Water Resources" unravels, the same green revolution which made India self-sufficient in food, ended up devaluing its waters in terms of both quantity and quality. Finally, in the third story, titled "Water Sustainability for Sustainable Agriculture: A Way Forward", a number of recommendations for recovering the lost value of water for agriculture are proposed. These include adoption of nature-based solutions such as watershed management, rainwater harvesting, and organic farming; recycle and reuse of wastewater; and use of micro-irrigation technologies, such as sprinklers, which increase the irrigation efficiency per unit of water used.

A view of Patesar Ahar showing one of its side embankments in Kaimur district, Bihar

How nature-based solutions can contribute to restoring the economic value of water for agriculture is further illustrated by two case studies. The first one, titled "Ahar-Pyne: A Nature-Based Solution for Water for Agriculture in Bihar", published in September 2018, describes an ingenious traditional irrigation system developed more than 2,300 years ago, in an area where the landscape is unsuitable for agriculture due to limited rainfall, low water retention capacity of soil, and a steep gradient. The Ahar-Pyne system is a highly efficient way to value all the rainfall that is received, using it not only to fulfil agricultural water needs of local communities, but also for groundwater recharge that helps yield drinking water, flood control, drought resilience, and soil moisture enhancement.

Water from Karath Pyne, which originates from Patesar Ahar, being diverted into a paddy field for irrigation in Kaimur district, Bihar

Masurdi Khadin inundated with runoff received from its catchment - in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

The second case study is titled "Khadin: A Nature-Based Solution for Water for Agriculture in the Great Indian Desert", published in October 2018. Here, flourishing agriculture is practiced using recharged soil moisture that is procured from rainwater harvesting in agricultural fields. This harvested rainwater also recharges drinking water aquifers, besides being directly used for irrigating 'kharif' (monsoon) crops. The very practice of this nature-based solution and the rich traditional knowledge behind it exemplifies the high value placed on every drop of rainfall that is received in this water-parched region in Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan. The mean annual rainfall here is barely 100 mm, with intermittent drought years.

Masurdi Khadin with standing winter (rabi) crops like wheat, chickpeas and mustard - in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan

Groundwater being filled in a shrimp farming pond in village Lahli, Rohtak district, Haryana

There are several other ways in which water is valued economically. One of these is through sale of water for drinking. Packaged drinking water – sold and traded widely in sachets and bottles in urban and sometimes rural areas – has an increasing economic value as it supports business as well as livelihoods. This is presented in a story titled "Water for Profit", published in May 2016. Another way is through aquaculture, an example of which is presented in a story titled "Inland Saline Water Shrimp Farming in Agricultural Fields of Haryana". While aquaculture is practiced widely in the country, this story describes an attempt to 're-value' water for economic gain in the semi-arid and arid regions of northern India after its 'de-valuation' when used for irrigated agriculture during green revolution. The story further critiques that this ostensible 're-valuing' could actually lead to greater devaluation due to deep environmental impact on the local water resources.

White shrimps at the stage of about 70 days in a shrimp farming pond in village Lahli, Rohtak district, Haryana

River Bhagirathi – one of the headstreams of Ganga – meandering its way through valleys separating the high peaks of the Himalayas in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

Unlike the previous themes, the theme of water values and associated processes in connection with environment can be understood as a double-sided coin, with environment being largely considered as the natural environment or nature. Water is an inextricable part of nature and therefore, on one side of this coin is "nature for water" while on the other one is "water for nature". This is because nature sustains and nurtures the 'water cycle', while, water in turn, nurtures nature. Hence, the environmental value of water is paramount, and every effort should be directed to upkeep this fundamental value. The role of mountainous ecosystems in nurturing water and thereby supporting societal development, is outlined in a story titled "Nature for Water: A Tale from the Himalayas", published in March 2018. Despite its importance, the environmental value of water on both sides of the coin are being increasingly degraded through various anthropogenic actions. The underlying pathways and the resultant consequences thwarting the enjoyment of the various instrumental values of water like drinking, livelihoods, cultural pursuits, etc. are presented in a story titled "Degradation of Nature and its Impact on Water", published in April 2018.

Reforestation with Chir Pine on denuded slopes at Chirbasa near Gaumukh in Uttarkashi district, Uttarakhand

Given the degradation of nature and its implications for realization of the intrinsic and instrumental values of water, there is an urgent need for action to reinstate and strengthen the lost environmental values of water. A photo story titled "Protection and Restoration of Nature for Water: Some Observations and Thoughts", published in May 2018, outlines mechanisms and initiatives towards this end. Protection and restoration of nature is the first and foremost action, with an emphasis on adoption of nature-based solutions. It is important to note that nature-based solutions have been a part of the traditional water management practices in India, that not only promote water sustainability in practical terms, but also play a strong positive role in raising the value of water in society. But equally important are the necessary processes. Towards this end, the photo story emphasizes the need to adopt a participatory approach, engaging all stakeholders including industries, businesses, government, non-governmental agencies, and the local communities. Moreover, it underscores the need for appropriate communication and sensitization of all stakeholders, which is also the cornerstone for raising the value of water in society.

Untreated municipal sewage discharged into river Ganga at Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

On the side of the 'water for nature', an important consideration is the wastewater generated from human use of water. This water, which constitutes a huge amount, must be returned to nature. However, it is polluted with multitude of microbial, chemical and physical contaminants. If returned in this state, it can thoroughly harm nature, destruct the water cycle and seriously challenge the various values associated with water. The issues concerning water pollution and wastewater are discussed in a series of photo stories on MWS under the category of 'water and environment'. The first of these, titled "Pollution of Water Sources Differently", published in July 2016, describes the different pathways through which the rivers, lakes, tanks, ponds and other water sources of India are getting increasingly polluted. Another story titled "Problems of Wastewater: An Overview", published in March 2017, presents the varied dimensions of wastewater as a serious challenge for sustainable water management in India. It is obvious that if the challenge remains unaddressed, it will become impossible to upkeep the intrinsic as well as the diverse instrumental values of water for nature and society.

Collection Well at the common effluent treatment plant (CETP) in Jajmau industrial area, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh

In a quest to address the challenges posed by the colossal amounts of wastewater generated in India, a photo story titled "Integrated Approach for Encountering Wastewater Challenges", published in May 2017, delineates an approach based in multi-pronged efforts. On the quantitative front, it proposes the need to draw realistic estimations of the wastewater generated from different sources and ensure adequate facilities for their treatment. On the qualitative front, it proposes the need to ensure adequate functional arrangements for recycle of wastewater, at both centralized and decentralized scales. Finally, it underlines the need to generate widespread awareness among all water users regarding the challenges posed by wastewater and to secure the right actions on their behalf. Obviously, such actions are extremely important in the direction of safeguarding and upholding both intrinsic and instrumental values of water. Reuse of wastewater is an integral component of the above approach that can imply 'revaluing' the wastewater in its treated or partially treated form, which in turn can help support the core 'water valuation' process. A story on this theme is presented under the title "Wastewater Reuse: Some Reflections", published in April 2017.

Treated blackwater being drawn from a Sulabh effluent treatment plant attached to a biogas digester at the Sulabh toilet-cum-bath complex in Shirdi, Maharashtra

A case study that supports an integrated approach for encountering the wastewater challenge is presented under the title "Best Practices in Blackwater Management: The Case of Sulabh International", published in June 2017. The story describes a decentralized integrated blackwater management system pioneered and practiced by Sulabh International Social Service Organization. In this system, blackwater from the toilets is first collected and treated in an on-site anaerobic digester for biogas production. The emergent effluent is next recycled to remove color, odor and pathogens to make it available for multiple non-potable reuses. This signifies an attempt to value as well as revalue water for various instrumental purposes in society.

Devotees praying and offering sacred waters of Sangam (the confluence of rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Sarasvati) to deities at Prayag (Allahabad), Uttar Pradesh

The theme of water values in relation to culture represents a double-sided coin, just like the previous theme on water and environment. Thus, on one side of the coin lies 'water for culture' while the other side has 'culture for water'. The first side incorporates the instrumental values that water holds for carrying out different cultural pursuits. The second side incorporates those cultural values and even practices that help uphold the intrinsic and instrumental values of water. An elaboration of this double-sided coin in the context of religion in India is presented in a photo story titled "Water and Religion: Relevance of their Connection", published in August 2017. Using primarily the context of Hinduism, this story describes how sacred values are widely attached to water and water bodies, with rivers like Ganga even symbolized as goddesses. Many Hindu rituals and practices are woven around water. Epitomizing the relationship between water and religion as the 'water-religion-society' continuum, it illustrates how water not only enables the practice of religion, helping connect society to the supernatural, but also through the sacred concepts, beliefs and values connected to it, serves to establish its secular values in society. Thus, it helps enforce order and discipline, obliging human beings to value its importance as nature's gift and act to enhance its sustainability.

Devotees struggling to perform Chhath Puja in the scanty waters of degraded Yamuna river in North-East district, National Capital Territory of Delhi

Despite the central values of water vis-a-vis religion as described above, the practice of these values is facing severe challenges in contemporary times due to the different kinds of onslaughts on water and nature through anthropogenic actions. These challenges and their consequences for religious beliefs and practices are outlined in a photo story titled "Water and Religion: Contemporary Challenges Impacting their Connection", published in September 2017. The challenges are two-pronged. While on the one hand, the sacred values attached to water and water sources are getting eroded or undervalued in society, the non-availability of clean and pure water in adequate quantities also hampers fulfilment of the sacred values connected to the ritual and religious observances. An important repercussion is that since the religious beliefs, values and practices are a means to promote the sustainability of water resources, in such situations, access to adequate and good quality water for various secular uses like drinking and irrigation also ultimately gets affected.

Conglomeration of devotees for Kumbh Snan on the banks of river Ganga at Har ki Pauri, Haridwar, Uttarakhand

A case study portraying the water values connected to religion and the challenges is presented in a story titled "Kumbh: The Biggest Bathing Festival on Planet Earth", published in June 2016. Kumbh is India's oldest and most famous ritual bathing festival, which epitomizes the sacred and spiritual value attached to water within the scope of Hinduism. It is held at the same place every 12 years, at four venues, namely Haridwar, Ujjain, Nashik and Prayag (Allahabad) along the sacred rivers Ganga, Godavari, Kshipra and at the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati respectively. It is reckoned as the world's largest peaceful religious congregation where hundreds of millions of people converge from all corners of the country to undertake the Kumbh Snan - holy bath in the sacred river water. Apart from presenting the varied dimensions of Kumbh across its different venues in India, the story notes that in recent times, the sacred waters in the rivers at the Kumbh venues are increasingly facing a challenge due to diminishing quantities and deteriorating quality. To temporarily address the problem, other water uses are often curtailed in the area during Kumbh in order to maintain adequate and clean water flow in the river. However, if permanent solution is not applied, it is feared that fulfilment of this important ritual function of the holy rivers may become difficult, disrupting celebration of this great water pilgrimage, in turn affecting Indian religious and cultural ethos.

Cleaning of river Ganga near Dashashwamedh Ghat in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh

Finally solutions to the problems discussed above are presented in a story titled "Water and Religion: The Way Forward for Strengthening their Connection", published in October 2017. The story proposes an approach at two levels: pragmatic and ideological. On the pragmatic side, there is need to stop pollution and clean the existing pollution in sacred water bodies, restore river connectivity by removing dams, remove encroachment in sacred water bodies, and launch rooted public campaigns in protest against degradation of sacred water bodies. At the ideological level, there is need to enhance and perpetuate the religious values concerning water using different means such as awareness campaigns, public speeches and presentations by religious leaders, value-based participatory learning for children, as well as public veneration at sacred sites adjoining water bodies. The latter is especially important for promoting and perpetuating respect for the religious values attached to water, arouse the consciousness in water users to reflect upon their actions especially those connected to sacred water bodies, initiate attitudinal and behavioral changes, and help transform them into more responsible water stakeholders. This, in turn will enable reinstatement of the intrinsic as well as instrumental values of water.

A mother, responsible for the upkeep of the health and hygiene of her son, giving him a bath in Bhojpur district, Bihar

The theme of water values vis-à-vis culture can also be seen in terms of how water values are gendered. This arises from the fact that gender itself represents socio-cultural constructs with respect to behavior, roles and responsibilities of women and men. The stories titled "Women and Water Needs from Gender Perspective" and "Men and Water Needs from Gender Perspective", published in April and September 2016 respectively, elaborate the diverse water needs of women and men as water users. It is obvious that if water needs of the two groups are gendered, so would be the corresponding water values. And, further, within a gender group, there might be further fine-tuning of the values depending upon the importance that water holds for each type of user.

Men levelling water logged fields for paddy transplantation in Munger district, Bihar

A view of the 'garden lands' – coconut plantation with human settlement along an embankment in Kuttanad, Alappuzha district, Kerala

Another perspective on water values vis-à-vis culture presented on MWS deals with the instrumental values of water for day-to-day living. The photo story titled "Living Below the Sea Level: An Adaptation to Water Abundance in Kuttanad, Kerala", published in November 2018, throws light on the different dimensions of a unique form of human-nature-water relationship in Kuttanad, Kerala that enables local communities to survive and thrive amidst water abundance below the sea level. Kuttanad, part of the largest wetland complex and Ramsar site in India - the Vembanad-Kol ecosystem, is the region of lowest altitude in India. Nearly two-thirds of its approximately 900 sq.km. area located 0.6 - 2.2 m below mean sea level. For the more than two million inhabitants of the region, their habitations, daily chores, food, festivals, sports, transport, livelihoods and almost every aspect of socio-cultural life all revolve around their unique relationship with water, in turn rooted in the special cultural values they ascribe to water.

Youth enjoying a boat ride in Payippad river, district Alappuzha, Kerala

Leisure and recreation are also important cultural dimensions that lay the foundation of important water values in society. A presentation of some of the popular activities for recreation and enjoyment in India for which water is valued are presented in a photo story titled "Water for Recreation and Enjoyment", published in June 2016. The story contends that while water holds a central value in facilitating recreation and enjoyment, one must not overlook the fact that a number of these activities may leave significant negative impacts on water. Examples include water pollution due to house boats and hoteling in lakes or plunging of the water table due to maintenance of the recreation facilities with groundwater. The important message here is that while recreation and enjoyment based on water are important for emotional, psychological and cultural well-being in society, this should not be attempted at the cost of destroying the environmental values of water.

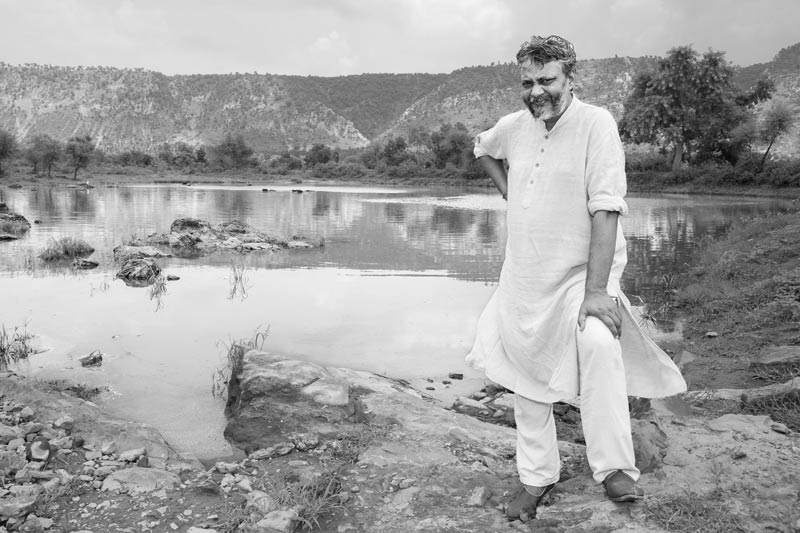

The 'Waterman of India' Rajendra Singh standing in front of Chountrawala Johad - the first johad in village Gopalpura where he started his work together with local villagers in 1985 - in Alwar district, Rajasthan

Finally, a number of photo stories on MWS under the category of 'water leaders' present the contributions of individual grassroots leaders to valuing water that helped achieve water sustainability in local communities. These leaders understood, promoted and motivated local action rooted in the notion that water has multiple values in society which are closely interconnected and inter-dependent. In general, working within the framework of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), these leaders initiated action for reinstating the environmental values of water, and this in turn, helped restore the intrinsic values of water, ultimately, enabling restoration of degraded water resources, and enabling people to enjoy the multiple values of water in society. The related stories are titled "Jaya Devi: The Water Lady", "Rajendra Singh: The Waterman of India", and "Chattar Singh Jam: The Water Wizard of Thar Desert", published consecutively in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively.

Though water values have existed in society since time immemorial, the need to 'value water' for achieving water sustainability and the related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has been a rather late realization globally. For MWS, the multiple values that water holds for society have been a central interest from the beginning. In fact, the origin of this realization goes much before the inception of MWS in 2016. While conducting field work across numerous sites in rural and urban India, its founders realized early that several of the sustainability challenges facing the country's water resources had their origin in competing interests of diverse users rooted in the different ways that they valued water. For example, while for an industry, the economic value was important, for the local community, the value was related to drinking and cultural practices. They also realized that if water sustainability is to be achieved, there is need to reconcile these different values, which in turn, requires an understanding of the multiple values under one common roof. Hence MWS incorporated the notion of 'valuing water' as a cross-cutting foundational pillar and started publishing photo stories classified under the 4 major water-use themes, namely, drinking water, water and livelihoods, water and environment, and water and culture.

The World Water Day 2021 theme of 'valuing water' has given MWS the opportunity to express this foundational pillar explicitly by revisiting all the photo stories published so far, integrating them as seen through this common lens. In this process, this photo story proposes an alternate holistic framework on 'valuing water'. This framework has two core dimensions. The first is the philosophical or ideational dimension, which deals with the different values that are attached to water. Most broadly, these are the 'intrinsic' and the 'instrumental' values. The former primarily considers water as 'nature's gift' or natural resource while the latter relate to the practical societal dimensions, such as drinking, domestic use, livelihoods, businesses, religious practices, festivals, sports, leisure, transport, and many more. There is a clear cause-and-effect relationship between these two types of values because the instrumental values are not possible to be realized in the absence of the intrinsic values. The second core aspect of the 'valuing water' concept is the pragmatic or action component. Every society must have mechanisms to ensure the upkeep of the values ascribed to water. In India, the strong socio-cultural traditions, embedded in the religious, spiritual or other cultural realms, or even in the traditional science and technology, reflect different mechanisms for the same. Unfortunately, these mechanisms and their underlying values are getting increasingly challenged in the light of the invasion of modern ideologies, technologies, and value-orientations. For example, instead of being valued as a 'gift of nature', today water is increasingly attributed the value of a 'commodity' that can be sold and purchased in the market. In fact, the emphasis on commoditization of water tends to replace those values that cannot be essentially measured in monetary terms. Such deep changes in value-orientations, can deliver death blows to this finite sensitive natural resource, and this is becoming increasingly evident.

Given such traditions and the rapidly transforming circumstances, this photo story further contends that in order to achieve water sustainability, the need of the hour in India and globally is to move beyond the framework of "valuing water" proposed by the UN-initiated and other global efforts to design and implement a deeper comprehensive approach for "re-valuing water". This approach should start with identification of the multiple values of water already existing in society and aim at reinstating or rediscovering those intrinsic values which stand eroded in present times, and also those instrumental values, particularly cultural ones, that reinforce the former. An example here would be the sacred values attached to water. The approach should include pragmatic steps promoting the environmental values of water, such as ecological restoration of water bodies (in terms of quantity and quality), recharge of degraded aquifers, and above all, restoration of nature for water. This would enable rejuvenation or introduction of cultural practices that can reinforce or enable realization of the different water values. The entire approach should be grounded in the concept of integrated water resources management (IWRM) where the integration of all stakeholders in planning, decision–making and action is essential. Thus, the approach should be implemented through an inclusive participatory approach that involves everyone in society – women, men, students, teachers, politicians, planners, bureaucrats, companies, businesspersons, non-governmental organizations, or any other individual or institutional actors connected to water directly or indirectly. Further, since water is a local resource that is ultimately used at the local scale and is associated with locally-ascribed values and worldview, its governance should be as much decentralized as possible. Hence "bottom-up" approaches which involve all local stakeholders should be adopted for value-based decisions and actions.

For achieving water sustainability through a comprehensive approach of 're-valuing water' involving the effective participation of all stakeholders, their awareness-building and sensitization through effective means of communication is essential. MWS has been continuously contributing towards this end since its vision and mission is to initiate positive changes in attitude, behavior, policy and action regarding water resources management through enhanced water sensitivity amongst different water stakeholders. MWS has adopted visual medium as a time-tested, popular and effective means of communication to inform, educate and communicate with different water stakeholders,. It is the first platform of its kind in the world that engages in sensitizing the masses on various dimensions of water resources management only through the medium of photo stories which provide evidence and also simplify representations, with one photograph speaking a thousand realistic words. As this story exhibits, the photo stories on MWS speak about and are grounded in discussions on the diverse values of water in society and the varied ways to upkeep and promote the same. It is hoped that these photo stories will help enhance awareness about water values and bring about long-lasting attitudinal and behavioral changes towards greater water sustainability. While visual communication is the most effective way of communicating with the masses, currently there exist very few such organized efforts nationally and internationally that engage in visually communicating on issues, perspectives, and knowledge regarding water in an integrated manner. The efforts of MWS and these few others are important but just like a drop in the ocean. More professionals and institutions need to come forward and join hands in this venture. There is also need to build new collaborations between professionals and institutions so that joint efforts can make bigger impacts.